Egon Friedell

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

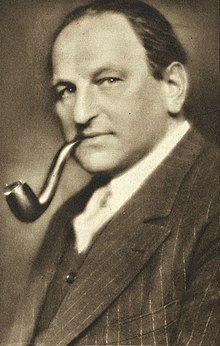

Egon Friedell (born Egon Friedmann; 21 January 1878, in Vienna – 16 March 1938, in Vienna) was a prominent Austrian cultural historian, playwright, actor and Kabarett performer, journalist and theatre critic. Friedell has been described as a polymath. Before 1916, he was also known by his pen name Egon Friedländer.

Early life[edit]

Friedell's parents had immigrated to Vienna from the eastern parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[1] Friedell was the second child of Jewish parents, Moriz Friedmann and Karoline (née Eisenberger), who were running a silk manufactory in Mariahilf. His older brother, Oskar Friedmann , also later became a writer and journalist.

His mother left the family for another man when he was one year old, from then on he lived with his father. The divorce was made in 1887. After his father's death in 1889, Friedell lived with his aunt in Frankfurt am Main, where he would attend school, until he was expelled for unruly behaviour three years later. Even at this young age, Friedell was considered a trouble maker and free thinker. In 1897, he renounced Judaism and converted to the Lutheran faith.

He attended several schools in Austria and Germany. Whilst attending school in Heidelberg in 1897, he already attended lectures on history of philosophy by Kuno Fischer.[2]

In 1899, he finally passed his Abitur (exit examination) after four attempts, in Bad Hersfeld.

After graduation, he enrolled in Heidelberg University to study under the historian of philosophy and follower of Hegel, Kuno Fischer.

Also in 1899, he had come of age and accepted his part of his father's inheritance. This enabled him to buy a tenement in Vienna at Gentzgasse 7, where he lived from then on. This is also where he died. Neither of the brothers wanted to continue running the father's factory.

From 1900 to 1904, Egon Friedell studied philosophy and German literature in Vienna. During that time he met Peter Altenberg and began writing articles for März and Die Schaubühne.

In 1904, he received his PhD for the dissertation on Novalis als Philosoph, which he wrote under the guidance of Friedrich Jodl. His dissertation was published soon after at Bruckmann Verlag in Munich.[2]

Actor, theatre critic, essayist, translator and biographer[edit]

In 1905, he started publishing texts in Karl Kraus's journal Die Fackel. The first was Vorurteile (issue no. 190), which included the following statement: "The worst prejudice we acquire during our youth is the idea that life is serious. Children have the right instincts: they know that life is not serious, and treat it is a game..." In the following issue he published Die Lehrmittel and Das schwarze Buch, which was co-authored with Peter Altenberg. Then followed by Zwei Skizzen: Der Panamahut & Die Bolette (issue 193), Pilatus (issue 201) and Ein Schmerzensschrei (issue 202).[3] After these texts were published, he and Kraus fell out with each other. In 1906, Friedell began kabarett performances at venues called Cabaret Nachtlicht and Hölle.

In 1907 he directed at Intimes Theater in Vienna, which was run by his brother, Oskar Friedmann.[1] There, he staged plays by August Strindberg, Frank Wedekind and Maurice Maeterlinck and brought them to the audience in Vienna for the first time. Friedell was doing lighting, acting and directing.

Between 1908 and 1910 Friedell worked as the artistic director of the Cabaret Fledermaus, named after the Johann Strauss operetta. Most pieces were written either by Peter Altenberg or jointly by Friedell and Alfred Polgar, who were nicknamed the "Polfried AG".[4] He also was acting there.[5] Other people involved were Oscar Straus, Hermann Bahr, Franz Blei, Erich Mühsam, Hanns Heinz Ewers, Alexander Roda Roda and Frank Wedekind.[6] Fritz Lang described his impressions of the Fledermaus: "There, amid Jugendstil decor, Kokoschka mounted his Indian fairy tale "Des getupfte Ei" ["The Dotted Egg"] on slides, writer Alfred Polgar [...] read his short prose and caustic commentary, and Friedell and other authors of rising repute presented their sketches and short plays."[7] During this time, Friedell continued to publish essays and one-act plays. His first literary effort was Der Petroleumkönig (Petrol king) in 1908. The parody Goethe im Examen, written jointly Alfred Polgar, in which he also played the leading role, made him famous in German speaking countries and got mentioned in the Sunday Times. He played this role repeatedly until 1938. Also in that time he wrote Soldatenleben im Frieden.

In 1910, Friedell was commissioned by publisher Samuel Fischer to write a biography of the poet Peter Altenberg. Fischer, who had expected something light, was unsatisfied with Friedell's analysis and critique of culture titled Ecce poeta, and the book was not promoted in any way. Hence, the book was a commercial failure, but served to mark the beginning of Friedell's interest in cultural history.[8]

He frequented the so called "literary cafés" among the Viennese coffee houses, notably the Café Central, where many notable people were patrons and where he got acquainted and befriended with many of them.[9] In 1912, Friedell went to Berlin, wrote and performed in cabarets. In 1913, he temporarily worked as an actor for director Max Reinhardt. In 1914, suffering from alcoholism and obesity, Friedell was forced to undergo treatment at a sanatorium near Munich. Friedell was enthusiastic about the beginning of World War I, as were many of his contemporaries, and volunteered for military service but was rejected for physical reasons. In 1916, he officially changed his name to Friedell. Friedell published the Judas Tragedy in 1920 and it was staged at the Burgtheater in 1923.[10]

In 1922 published Quarry — Miscellaneous Opinions and Quotations. In 1924, while working as a critic for the journal Stunde, Friedell was fired as a "traitor", for making satirical remarks.

Between 1919 and 1924, Friedell worked as a journalist and theatre critic for various publishers including Die Schaubühne, Der Merker and Neues Wiener Journal. Between 1924 and 1927 he was ensemble cast at the Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna, which was directed by Max Reinhardt. There he played, amongst others, roles in The Servant of Two Masters, Fanny's First Play, Intrigue and Love, The Merchant of Venice. He played with famous actors such as Hans Moser and Heinz Rühmann.[1]

After 1927, health problems prevented any permanent commissions, and he worked as an independent essayist, editor and translator in Vienna.

Among the authors Friedell translated were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Christian Friedrich Hebbel in 1909, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Thomas Carlyle and Hans Christian Andersen in 1914, Johann Nestroy, and Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1924.

During his life he published 22 works with 15 different publishers. Additionally, he wrote for 17 different journals and newspapers. Since 1937, he worked on two unfinished books, which only were left as sketches: History of Philosophy and Novel on Alexander the Great.[11]

Cultural history[edit]

Cultural History of the Modern Age[edit]

During the early 1920s, Friedell wrote the three volumes of his Cultural History of the Modern Age, which describes events from the Black Death to World War I in an anecdotal format. In 1925, publisher Hermann Ullstein received the first volume, but was suspicious of the historiography of an actor. Five other publishers subsequently rejected the book. The first volume was finally published by Heinrich Beck in Munich in 1927 and the following two volumes in 1928 and 1931. The book proved very successful and allowed Friedell to continue his work as an author and has been translated into seven languages[citation needed]. His approach to history was influenced by Oswald Spengler and Jacob Burckhardt.[8]

For instance, Friedell writes; "All the classifications man has ever devised are arbitrary, artificial, and false, but simple reflection also shows that such classifications are useful, indispensable, and above all unavoidable since they accord with an innate aspect of our thinking." Friedell summed up the Congress of Vienna as: "the Tsar of Russia falls in love for everyone; the King of Prussia thinks for everyone, the King of Denmark speaks for everyone; the King of Bavaria drinks for everyone; the King of Württemberg eats for everyone … and the Emperor of Austria pays for everyone."[12]

A Cultural History of Antiquity[edit]

Friedell's A Cultural History of Antiquity was planned in three volumes. Because his publisher in Germany Heinrich Beck was, since 1935, not allowed to publish any of his works, the first volume on Cultural History of Egypt's Land and of the Ancient Orient was published in 1936 by the Helikon-Verlag in Zürich.

The second volume Cultural History of Ancient Greece was unfinished and published in Munich in 1950. Due to his death, he couldn't write the third volume on Cultural History of the Romans.

Censorship and suicide[edit]

In 1933, when the Nazis came to power in Germany, Friedell described the regime as: "the realm of the Antichrist. Every trace of nobility, piety, education, reason is persecuted in the most hateful and base manner by a bunch of debased menials".

In 1937, Friedell's works were banned by the National Socialist regime as they did not conform to the theory of history promoted by the NSDAP, and all German and Austrian publishers refused to publish his works.

On the occasion of the Anschluss of Austria, anti-semitism was rampant: Jewish men and women were being beaten in the streets and their businesses and synagogues ransacked or destroyed. Friedell, knowing that he could be arrested by the Gestapo, began to contemplate ending his own life. Friedell told his close friend, Ödön von Horváth, in a letter written on 11 March: "I am always ready to leave, in every sense."

On 16 March 1938, at about 22:00, two SA men arrived at Friedell's house to arrest him. While they were still arguing with his housekeeper, Friedell, aged 60, committed suicide by jumping out of the window. Before leaping, he warned pedestrians walking on the sideway where he hit by shouting "Watch out! Get out of the way!"[13]

Friedell, of whom Hilde Spiel said "in him, the exhilarating fiction of the homo universalis rose once again", was interred in the protestant cemetery in Simmering in Vienna.

In 1954, a street in Vienna was named after him.[14] In 1978, the Austrian postal service issued a stamp with his portrait in celebration of his 100th birthday.[15] In 2005, his grave was given the honor of becoming an Ehrengrab.[16]

Works[edit]

- Absinth "Schönheit" (Peter Altenberg & Egon Friedell) - eLibrary Austria Project (elib austria text in German)

- Das schwarze Buch (Peter Altenberg & Egon Friedell) - eLibrary Austria Project (elib austria text in German)

- Der Petroleumkönig, 1908

- Der Nutzwert des Dichters - eLibrary Austria Project (elib austria text in German)

- Goethe, 1908 - eLibrary Austria Project (elib austria text in German)

- Ecce poeta, 1912

- Von Dante zu d'Annunzio, 1915

- Die Judastragödie, 1920

- Steinbruch, 1922

- Ist die Erde bewohnt? 1931 - eLibrary Austria Project (elib austria text in German)

- Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit, 1927–31 (Engl. transl)

- Kulturgeschichte Ägyptens und des alten Orients, 1936

- Kulturgeschichte Griechenlands, 1940

- Die Reise mit der Zeitmaschine, 1946 - a sequel to H. G. Wells' The Time Machine, translated by Eddy C Bertin into English and republished as The Return of the Time Machine

- Kulturgeschichte des Altertums, 1949

- Das Altertum war nicht antik, 1950

- Kleine Porträtgalerie, 1953

- Abschaffung des Genies. Essays bis 1918, 1984

- Selbstanzeige. Essays ab 1918, 1985

External links[edit]

- Anecdotage.Com - Thousands of true funny stories about famous people. Anecdotes from Gates to Yeats at anecdotage.com

- Petri Liukkonen. "Egon Friedell". Books and Writers.

- Essay on Egon Friedell by Clive James from "Cultural Amnesia"

- Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit - commented radio reading of the unabridged text (130 online archived episodes, broadcast 2008–2014 in German language) - ORANGE 94.0 Freies Radio Wien

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/friedell-egon

- https://www.nzz.ch/feuilleton/buecher/reichtum-an-problemen-1.18148038

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Bernhard Viel (2013), "Egon Friedell: Der geniale Dilettant". ISBN 978-3-406-63850-3

- ^ a b Elisabeth Flucher (2015), Traces of Immanuel Kant in Friedell’s Work. In: Violetta Waibel, Detours: Approaches to Immanuel Kant in Vienna, in Austria, and in Eastern Europe. ISBN 9783847104810. page 365

- ^ "Die Fackel text". Austrian Academy Corpus.

- ^ "Anfänge". deutsch.pi-noe.ac.at. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Egon Friedell".

- ^ Karin Ploog (2015): ...Als die Noten laufen lernten...Band 2: Kabarett-Operette-Revue-Film-Exil ... ISBN 3734753163, page 38

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (2013). "Chapter One: 1890-1911". Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0816676552 – via The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Friedell, Egon".

- ^ Shachar M. Pinsker (2018), A Rich Brew: How Cafés Created Modern Jewish Culture ISBN 9781479827893

- ^ "Literatur - Dichter und Dilettant". 15 March 2013.

- ^ Elisabeth Flucher (2015), Traces of Immanuel Kant in Friedell’s Work. In: Violetta Waibel, Detours: Approaches to Immanuel Kant in Vienna, in Austria, and in Eastern Europe. ISBN 9783847104810. page 367

- ^ British Government. Foreign & Commonwealth Office, 18 December 2012. Speech - The Foreign Office, one of the great offices of state. by William Hague, Foreign Secretary

- ^ Sack, Harald (16 March 2018). "Egon Friedell's Fascinating Cutural Histories". SciHi Blog. yovisto GmbH. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Egon-Friedell-Gasse".

- ^ "Egon Friedell".

- ^ "Archivmeldung: Ehrengrab-Widmung für Schriftsteller Egon Friedell". 16 March 2005.

- 1878 births

- 1938 suicides

- 20th-century Austrian writers

- 20th-century Austrian male actors

- 20th-century Austrian historians

- Austrian philosophers

- Austrian journalists

- Austrian theatre critics

- Kabarettists

- Jewish philosophers

- Jewish historians

- Jewish Austrian male actors

- Jews from Austria-Hungary

- Austrian Lutherans

- Jewish Austrian writers

- Converts to Lutheranism from Judaism

- Writers from Vienna

- People from Währing

- Austrian expatriates in Germany

- Suicides by jumping in Austria

- Burials at the Vienna Central Cemetery

- Austrian male stage actors

- 1938 deaths

- Male actors from Vienna