Day of the Tentacle

| Day of the Tentacle | |

|---|---|

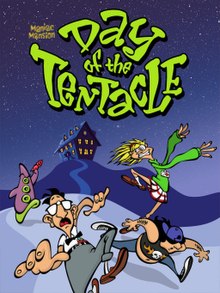

Cover art by Peter Chan depicting the three playable characters (Bernard, Hoagie and Laverne) running from the tentacle antagonist | |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts[a] |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts[b] |

| Director(s) | |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | Peter Chan |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | |

| Engine | SCUMM |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Day of the Tentacle, also known as Maniac Mansion II: Day of the Tentacle,[5][6] is a 1993 graphic adventure game developed and published by LucasArts. It is the sequel to the 1987 game Maniac Mansion. The plot follows Bernard Bernoulli and his friends Hoagie and Laverne as they attempt to stop the evil Purple Tentacle - a sentient, disembodied tentacle - from taking over the world. The player takes control of the trio and solves puzzles while using time travel to explore different periods of history.

Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer co-led the game's development, their first time in such a role. The pair carried over a limited number of elements from Maniac Mansion and forwent the character selection aspect to simplify development. Inspirations included Chuck Jones cartoons and the history of the United States. Day of the Tentacle was the eighth LucasArts game to use the SCUMM engine.

The game was released simultaneously on floppy disk and CD-ROM to critical acclaim and commercial success. Critics focused on its cartoon-style visuals and comedic elements. Day of the Tentacle has featured regularly in lists of "top" games published more than two decades after its release, and has been referenced in popular culture. A remastered version of Day of the Tentacle was developed by Schafer's current studio, Double Fine Productions, and released in March 2016, for OS X, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Windows, with an iOS and Linux port released in July the same year, and then later for Xbox One in October 2020.

Gameplay[edit]

Day of the Tentacle follows the point-and-click two-dimensional adventure game formula, first established by the original Maniac Mansion. Players direct the controllable characters around the game world by clicking with the computer mouse. To interact with the game world, players choose from a set of nine commands arrayed on the screen (such as "pick up", "use", or "talk to") and then on an object in the world. This was the last SCUMM game to use the original interface of having the bottom of the screen being taken up by a verb selection and inventory; starting with the next game to use the SCUMM engine, Sam & Max Hit the Road, the engine was modified to scroll through a more concise list of verbs with the right mouse button and having the inventory on a separate screen.[7][8]

Day of the Tentacle uses time travel extensively; early in the game, the three main protagonists are separated across time by the effects of a faulty time machine. The player, after completing certain puzzles, can then freely switch between these characters, interacting with the game's world in separate time periods. Certain small inventory items can be shared by placing the item into the "Chron-o-Johns", modified portable toilets that instantly transport objects to one of the other time periods, while other items are shared by simply leaving the item in a past time period to be picked up by a character in a future period. Changes made to a past time period will affect a future one, and many of the game's puzzles are based on the effect of time travel, the aging of certain items, and alterations of the time stream. For example, one puzzle requires the player, while in the future era where Purple Tentacle has succeeded, to send a medical chart of a Tentacle back to the past, having it used as the design of the American flag, then collecting one such flag in the future to be used as a Tentacle disguise to allow that character to roam freely.[9]

The whole original Maniac Mansion game can be played on a computer resembling a Commodore 64 inside the Day of the Tentacle game; this practice has since been repeated by other game developers, but at the time of Day of the Tentacle's release, it was unprecedented.[10]

Plot[edit]

Five years after the events of Maniac Mansion, Purple Tentacle—a mutant monster and lab assistant created by mad scientist Dr. Fred Edison—drinks toxic sludge from a river behind Dr. Fred's laboratory. The sludge causes him to grow a pair of flipper-like arms, develop vastly increased intelligence, and have a thirst for global domination.[11] Dr. Fred plans to resolve the issue by killing Purple Tentacle and his harmless, friendly brother Green Tentacle, but Green Tentacle sends a plea of help to his old friend, the nerd Bernard Bernoulli. Bernard travels to the Edison family motel with his two housemates, deranged medical student Laverne and roadie Hoagie, and frees the tentacles. Purple Tentacle escapes to resume his quest to take over the world.[12]

Since Purple Tentacle's plans are flawless and unstoppable, Dr. Fred decides to use his Chron-o-John time machines to send Bernard, Laverne, and Hoagie to the day before to turn off his Sludge-o-Matic machine, thereby preventing Purple Tentacle's exposure to the sludge.[13] However, because Dr. Fred used an imitation diamond rather than a real diamond as a power source for the time machine, the Chron-o-Johns break down in operation. Laverne is sent 200 years in the future, where humanity has been enslaved and Purple Tentacle rules the world from the Edison mansion, while Hoagie is dropped 200 years in the past, where the motel is being used by the Founding Fathers as a retreat to write the United States Constitution. Bernard is returned to the present. To salvage Dr. Fred's plan, Bernard must acquire a replacement diamond for the time machine, while both Hoagie and Laverne must restore power to their respective Chron-o-John pods by plugging them in.[14] To overcome the lack of electricity in the past, Hoagie recruits the help of Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Fred's ancestor, Red Edison, to build a superbattery to power his pod, while Laverne evades capture by the tentacles long enough to run an extension cord to her unit. The three send small objects back and forth in time through the Chron-o-Johns and make changes to history to help the others complete their tasks.

Eventually, Bernard uses Dr. Fred's family fortune of royalties from the use of their likeness in Maniac Mansion to purchase a real diamond, while his friends manage to power their Chron-o-Johns. Soon, the three are reunited in the present. Purple Tentacle arrives, hijacks a Chron-o-John, and takes it to the previous day to prevent them from turning off the sludge machine; he is pursued by Green Tentacle in another pod.[15] With only one Chron-o-John pod left, Bernard, Hoagie, and Laverne use it to pursue the tentacles to the previous day, while Dr. Fred uselessly tries to warn them of using the pod together, referencing the film The Fly. Upon arriving, the trio exit the pod only to discover that they have been turned into a three-headed monster, their bodies merging into one during the transfer. Meanwhile, Purple Tentacle has used the time machine to bring countless versions of himself from different moments in time to the same day to prevent the Sludge-o-Matic from being deactivated.[16] Bernard and his friends defeat the Purple Tentacles guarding the Sludge-o-Matic, turn off the machine, and prevent the whole series of events from ever happening. Returning to the present, Dr. Fred discovers that the three have not been turned into a monster at all but have just gotten stuck in the same set of clothes; they are then ordered by Dr. Fred to get out of his house. The game ends with the credits rolling over a tentacle-shaped American flag, one of the more significant results of their tampering in history.

Development[edit]

Following a string of successful adventure games, LucasArts assigned Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer to lead development of a new game. The two had previously assisted Ron Gilbert with the creation of The Secret of Monkey Island and Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge, and the studio felt that Grossman and Schafer were ready to manage a project. The company believed that the pair's humor matched well with that of Maniac Mansion and suggested working on a sequel. The two developers agreed and commenced production.[17] Gilbert and Gary Winnick, the creators of Maniac Mansion, collaborated with Grossman and Schafer on the initial planning and writing.[17][18] The total budget for the game was about $600,000, according to Schafer.[19]

Creative design[edit]

In planning the plot, the four designers considered a number of concepts, eventually choosing an idea of Gilbert's about time travel that they believed was the most interesting. The four discussed what time periods to focus on, settling on the Revolutionary War and the future. The Revolutionary War offered opportunities to craft many puzzles around that period, such as changing the Constitution to affect the future. Grossman noted the appeal of the need to make wide-sweeping changes such as the Constitution just to achieve a small personal goal, believing this captured the essence of adventure games.[20] The future period allowed them to explore the nature of cause and effect without any historical bounds.[20] Grossman and Schafer decided to carry over previous characters that they felt were the most entertaining. The two considered the Edison family "essential" and chose Bernard because of his "unqualified nerdiness".[17] Bernard was considered "everyone's favorite character" from Maniac Mansion, and was the clear first choice for the protagonists.[20] The game's other protagonists, Laverne and Hoagie, were based on a Mexican ex-girlfriend of Grossman's and a Megadeth roadie named Tony that Schafer had met, respectively.[21] Schafer and Grossman planned to use a character selection system similar to the first game but felt that it would have complicated the design process and increased production costs. Believing that it added little to the gameplay, they removed it early in the process and reduced the number of player characters from six to three.[17] The dropped characters included Razor, a female musician from the previous game; Moonglow, a short character in baggy clothes; and Chester, a black beat poet. Ideas for Chester, however, morphed into new twin characters in the Edison family.[22] The smaller number of characters reduced the strain on the game's engine in terms of scripting and animation.[7]

The staff collaboratively designed the characters. They first discussed the character personalities, which Larry Ahern used to create concept art. Ahern wanted to make sure that the art style was consistent and the character designs were established early, in contrast to what had happened with Monkey Island 2, in which various artists came in later to help fill in necessary art assets as necessary, creating a disjointed style.[23] Looney Tunes animation shorts, particularly the Chuck Jones-directed Rabbit of Seville, What's Opera, Doc?, and Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century inspired the artistic design. The cartoonish style also lent itself to providing larger visible faces to enable more expressive characters.[23] Peter Chan designed backgrounds, spending around two days to progress from concept sketch to final art for each background.[22] Chan too used Looney Tunes as influence for the backgrounds, trying to emulate the style of Jones and Maurice Noble. Ahern and Chan went back and forth with character and background art to make sure both styles worked together without too much distraction. They further had Jones visit their studio during development to provide input into their developing art.[23] The choice of art style inspired further ideas from the designers. Grossman cited cartoons featuring Pepé Le Pew, and commented that the gag involving a painted white stripe on Penelope Pussycat inspired a puzzle in the game. The artists spent a year creating the in-game animations.[22]

The script was written in the evening when fewer people were in the office.[17][22] Grossman considered it the easiest aspect of production, but encountered difficulties when writing with others around.[17]

With a time travel story, I leave a bottle of wine somewhere, and it causes a bottle of vinegar to appear in the same place four hundred years later. Same basic idea: I do X over here, and it causes Y over there. Whether ‘over there’ means in the next room or 400 years in the future is irrelevant. I will say that it was really fun to think about the effects of large amounts of time on things like wine bottles and sweaters in dryers, and to imagine how altering fundamentals of history like the Constitution and the flag could be used to accomplish petty, selfish goals like the acquisition of a vacuum and a tentacle costume. We definitely enjoyed ourselves designing that game.

Dave Grossman on designing the game's puzzles[22]

Grossman and Schafer brainstormed regularly to devise the time travel puzzles and collaborated with members of the development team as well as other LucasArts employees. They would identify puzzle problems and work towards a solution similar to how the game plays. Most issues were addressed prior to programming, but some details were left unfinished to work on later.[17] The staff conceived puzzles involving the U.S.'s early history based on their memory of their compulsory education, and using the more legendary aspects of history, such as George Washington cutting down a cherry tree to appeal to international audiences.[20][22] To complete the elements, Grossman researched the period to maintain historical accuracy, visiting libraries and contacting reference librarians. The studio, however, took creative license towards facts to fit them into the game's design.[17][22]

Day of the Tentacle features a four-minute-long animated opening credit sequence, the first LucasArts game to have such. Ahern noted that their previous games would run the credits over primarily still shots which would only last for a few minutes, but with Tentacle, the team had grown so large that they worried this approach would be boring to players.[23] They assigned Kyle Balda, an intern at CalArts, to create the animated sequence, with Chan helping to create minimalist backgrounds to aid in the animation.[23] Originally this sequence was around seven minutes long, and included the three characters arriving at the mansion and releasing Purple Tentacle. Another LucasArts designer, Hal Barwood, suggested they cut it in half, leading to the shortened version as in the released game, and having the player take over when they arrive at the mansion.[23]

Technology and audio[edit]

Day of the Tentacle uses the SCUMM engine developed for Maniac Mansion.[17] LucasArts had gradually modified the engine since its creation. For example, the number of input verbs was reduced and items in the character's inventory are represented by icons rather than text.[7] While implementing an animation, the designers encountered a problem later discovered to be a limitation of the engine. Upon learning of the limitation, Gilbert reminisced about the file size of the first game. The staff then resolved to include it in the sequel.[17]

Day of the Tentacle was the first LucasArts adventure game to feature voice work on release.[c] The game was not originally planned to include voice work, as at the time, the install base for CD-ROM was too low.[20] As they neared the end of 1992, CD-ROM sales grew significantly. The general manager of LucasArts, Kelly Flock, recognizing that the game would not be done in time by the end of the year to make the holiday release, suggested that the team include voice work for the game, giving them more time.[20]

Voice director Tamlynn Barra managed that aspect of the game.[20] Schafer and Grossman described how they imagined the characters' voices and Barra sought audition tapes of voice actors to meet the criteria. She presented the best auditions to the pair. Schafer's sister Ginny was among the auditions, and she was chosen for Nurse Edna. Schafer opted out of the decision for her selection to avoid nepotism.[17] Grossman and Schafer encountered difficulty selecting a voice for Bernard.[17][22] To aid the process, Grossman commented that the character should sound like Les Nessman from the television show WKRP in Cincinnati. Barra responded that she knew the agent of the character's actor, Richard Sanders, and brought Sanders on the project.[17][24] Denny Delk and Nick Jameson were among those hired, and provided voice work for around five characters each.[17] Recording for the 4,500 lines of dialog occurred at Studio 222 in Hollywood. Barra directed the voice actors separately from a sound production booth. She provided context for each line and described aspects of the game to aid the actors.[25] The voice work in Day of the Tentacle was widely praised for its quality and professionalism in comparison to Sierra's talkie games of the period which suffered from poor audio quality and limited voice acting (some of which consisted of Sierra employees rather than professional talent).

The game's music was composed by Peter McConnell, Michael Land, and Clint Bajakian.[26] The three had worked together to share the duties equally of composing the music for Monkey Island 2 and Fate of Atlantis, and continued this approach for Day of the Tentacle.[26] According to McConnell, he had composed most of the music taking place in the game's present, Land for the future, and Bajakian for the past, outside of Dr. Fred's theme for the past which McConnell had done.[26] The music was composed around the cartoonish nature of the gameplay, further drawing on Looney Tunes' use of parodying classical works of music, and playing on set themes for all of the major characters in the game.[26] Many of these themes had to be composed to take into account different processing speeds of computers at the time, managed by the iMUSE music interface; such themes would include shorter repeating patterns that would play while the game's screen scrolled across, and then once the screen was at the proper place, the music would continue on to a more dramatic phrase.[26]

Day of the Tentacle was one of the first games concurrently released on CD-ROM and floppy disk.[25] A floppy disk version was created to accommodate consumers that had yet to purchase CD-ROM drives. The CD-ROM format afforded the addition of audible dialog. The capacity difference between the two formats necessitated alterations to the floppy disk version. Grossman spent several weeks reducing files sizes and removing files such as the audio dialog to fit the game onto six diskettes.[22]

Reception[edit]

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 95%[27] |

| Metacritic | 93/100[28] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| PC Gamer US | #46, The Best Games of All Time[29] |

| Computer Gaming World | Adventure Game of the Year, June 1994[30] #34, 150 Best Games of All Time[31] |

| Adventure Gamers | #1, Top 20 Adventure Games of All Time[32] |

| IGN | #60, Top 100 Games (2005)[33] #84, Top 100 Games (2007)[34] #82, Top 100 Videogame Villains (Purple Tentacle)[35] |

| PC Gamer UK | #30, The Top 100[36] |

Day of the Tentacle was a moderate commercial success; according to Edge, it sold roughly 80,000 copies by 2009. Tim Schafer saw this as an improvement over his earlier projects, the Monkey Island games, which had been commercial flops.[37] The game was critically acclaimed. Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World wrote in September 1993: "Calling Day of the Tentacle a sequel to Maniac Mansion ... is a little like calling the space shuttle a sequel to the slingshot". He enjoyed the game's humor and interface, and praised the designers for removing "dead end" scenarios and player character death. Ardai lauded the voice acting, writing that it "would have done the late Mel Blanc proud", and compared the game's humor, animation, and camera angles to "Looney Toons [sic] gems from the 40s and 50s". He concluded: "I expect that this game will keep entertaining people for quite some time to come".[38] In April 1994 the magazine said of the CD version that Sanders's Bernard was among "many other inspired performances", concluding that "Chuck Jones would be proud".[39] In May 1994 the magazine said of one multimedia kit bundling the CD version that "it packs more value into the kit than the entire software packages of some of its competitors".[40] Sandy Petersen of Dragon stated that its graphics "are in a stupendous cartoony style", while praising its humor and describing its sound and music as "excellent". Although the reviewer considered it "one of the best" graphic adventure games, he noted that, like LucasArts' earlier Loom, it was extremely short; he wrote that he "felt cheated somehow when I finished the game". He ended the review, "Go, Lucasfilm! Do this again, but do make the next game longer!".[41]

Phil LaRose of The Advocate called it "light-years ahead of the original", and believed that its "improved controls, sound and graphics are an evolutionary leap to a more enjoyable gaming experience". He praised the interface, and summarized the game as "another of the excellent LucasArts programs that place a higher premium on the quality of entertainment and less on the technical knowledge needed to make it run".[42] The Boston Herald's Geoff Smith noted that "the animation of the cartoonlike characters is of TV quality", and praised the removal of dead ends and character death. He ended: "It's full of lunacy, but for anyone who likes light-hearted adventure games, it's well worth trying".[43] Vox Day of The Blade called its visuals "well done" and compared them to those of The Ren & Stimpy Show. The writer praised the game's humor, and said that "both the music and sound effects are hilarious"; he cited the voice performance of Richard Sanders as a high point. He summarized the game as "both a good adventure and a funny cartoon".[44]

Lim Choon Wee of the New Straits Times highly praised the game's humor, which he called "brilliantly funny". The writer commented that the game's puzzles relied on "trial and error" with "no underlying logic", but opined that the game "remains fun" despite this issue, and concluded that Day of the Tentacle was "definitely the comedy game of the year".[45] Daniel Baum of The Jerusalem Post called it "one of the funniest, most entertaining and best-programmed computer games I have ever seen", and lauded its animation. He wrote that the game provided "a more polished impression" than either The Secret of Monkey Island or Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge. The writer claimed that its high system requirements were its only drawback, and believed that a Sound Blaster card was required to fully appreciate the game.[46] In a retrospective review, Adventure Gamers' Chris Remo wrote: "If someone were to ask for a few examples of games that exemplify the best of the graphic adventure genre, Day of the Tentacle would certainly be near the top".[47]

Day of the Tentacle has been featured regularly in lists of "top" games. In 1994, PC Gamer US named Day of the Tentacle the 46th best computer game ever.[29] In June 1994 it and Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers won Computer Gaming World's Adventure Game of the Year award. The editors wrote that "Day of the Tentacle's fluid animation sequences underscore a strong script and solid game play ... story won out over technological innovation in this genre".[30] In 1996, the magazine ranked it as the 34th best game of all time, writing: "DOTT completely blew away its ancestor, Maniac Mansion, with its smooth animated sequences, nifty plot and great voiceovers".[31] Adventure Gamers included the game as the top entry on its 20 Greatest Adventure Games of All Time List in 2004,[32] and placed it sixth on its Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games in 2011.[48] The game has appeared on several IGN lists. The website rated it number 60 and 84 on its top 100 games list in 2005 and 2007, respectively.[33][34] IGN named Day of the Tentacle as part of their top 10 LucasArts adventure games in 2009,[49] and ranked the Purple Tentacle 82nd in a list of top 100 videogame villains in 2010.[35] ComputerAndVideoGames.com ranked it at number 30 in 2008,[36] and GameSpot also listed Day of the Tentacle as one of the greatest games of all time.[10]

Legacy[edit]

Fans of Day of the Tentacle created a webcomic, The Day After the Day of the Tentacle, using the game's graphics.[34] The 1993 LucasArts game Zombies Ate My Neighbors features a stage dedicated to Day of the Tentacle. The artists for Day of the Tentacle shared office space with the Zombies Ate My Neighbors development team. The team included the homage after frequently seeing artwork for Day of the Tentacle during the two games' productions.[50] In describing what he considered "the most rewarding moment" of his career, Grossman stated that the game's writing and use of spoken and subtitled dialog assisted a learning-disabled child in learning how to read.[17] Telltale Games CEO Dan Connors commented in 2009 that an episodic game based on Day of the Tentacle was "feasible", but depended on the sales of the Monkey Island games released that year.[d][51]

In 2018, a fan-made sequel, Return of the Tentacle, was released free by a team from Germany.[52][53] The game imitates the art style of the Remastered edition and features full voice acting.[54][55]

Remasters[edit]

Special Edition[edit]

According to Kotaku, a remastered version of Day of the Tentacle was in the works at LucasArts Singapore before the sale of LucasArts to Disney in 2012. Though never officially approved, the game used a pseudo-3D art style and was nearly 80% complete, according to one person close to the project, but was shelved in the days before the closure of LucasArts.[56]

Remastered[edit]

A remastered version of Day of the Tentacle was developed by Schafer and his studio, Double Fine Productions. The remaster was released on March 22, 2016, for OS X, PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, and Windows,[57][58][59] with a Linux version released at July 11[60] together with a mobile port for iOS.[61] The PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita versions are cross-buy and also feature cross-save.[62][63] An Xbox One port came in October 2020.[64] The remastered game was released as a free PlayStation Plus title for the month of January 2017.[65][66]

Schafer credited both LucasArts and Disney for help in creating the remaster, which follows from a similar remastering of Grim Fandango, as well by Double Fine, in January 2015. Schafer said when they originally were about to secure the rights to Grim Fandango from LucasArts to make the remaster, they did not originally have plans to redo the other LucasArts adventure games, but with the passionate response, they got on the news of the Grim Fandango remaster, they decided to continue these efforts. Schafer described getting the rights to Day of the Tentacle a "miracle" though aided by the fact that many of the executives in the legal rights chain had fond memories of playing these games and helped to secure the rights.[67] 2 Player Productions, which has worked before with Double Fine to document their game development process, also created a mini-documentary for Day of the Tentacle Remastered, which included a visit to the Skywalker Ranch, where LucasArts games were originally developed, where much of the original concept art and digital files for the game and other LucasArts adventure games were archived.[68]

Day of the Tentacle Remastered retains its two-dimensional cartoon-style art, redrawn at a higher resolution for modern computers.[67] The high resolution character art was updated by a team led by Yujin Keim with the consultation of Ahern and Chan. Keim's team used many of the original sketches of characters and assets from the two and emulated their style with improvements for modern graphics systems.[23] Matt Hansen worked on recreating the background assets in high resolution.[20] As with the Grim Fandango remaster, the player can switch back and forth between the original graphics and the high-resolution version.[20] The game includes a more streamlined interaction menu, a command wheel akin to the approach used in Broken Age, but the player can opt to switch back to the original interface.[20] The game's soundtrack has been redone within MIDI adapted to work with the iMUSE system.[20] There is an option to listen to commentary from the original creators, including Schafer, Grossman, Chan, McConnell, Ahern, and Bajakian. The remaster contains the fully playable version of the original Maniac Mansion, though no enhancements have been made to that game-within-a-game.[57]

Day of the Tentacle Remastered has received positive reviews, with the PC version having an aggregate review score of 87/100 tallied by Metacritic.[69] Reviewers generally praised the game as having not lost its charm since its initial release, but found some aspects of the remastering to be lackluster. Richard Corbett for Eurogamer found the game "every bit as well crafted now as it was in 1993", but found the processes used to provide high-definition graphics from the original 16-bit graphics to making some of the required shortcuts taken in 1993 for graphics, such as background dithering and low animation framerates, more obvious on modern hardware.[70] IGN's Jared Petty also found the remastered to still be enjoyable, and found the improvement on the graphics to be "glorious", but worried that the lack of a hint system, as was added in The Secret of Monkey Island remastered version, would put off new players to the game.[71] Bob Mackey for USgamer found that while past remastered adventure games have highlighted how much has changed in gamers' expectations since the heyday of adventure games in the 1990s, Day of the Tentacle Remastered "rises above these issues to become absolutely timeless".[72]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Remastered version developed by Double Fine Productions.

- ^ Original release distributed in the United Kingdom by U. S. Gold.[4] Remastered version published by Double Fine Productions; Xbox One remastered version published by Xbox Game Studios.

- ^ Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis predates Day of the Tentacle by a month, but did not have voice work until an enhanced version released a year later in 1993.

- ^ Telltale Games co-developed the 2009 game Tales of Monkey Island with LucasArts.

References[edit]

- ^ "Game Zone". Derby Evening Telegraph. July 7, 1993. p. 12. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

Day of the Tentacle is available on IBM/PC at £42.99 and CD ROM version for £45.99

- ^ Black, Dorian (July 27, 1993). "Computer game gives players a certain flush of success". The Age. p. 30. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

Day of the Tentacle: Maniac Mansion II (CD-ROM) by Lucas Arts. Price: $89.95

- ^ "Retroradar: Retrodiary". Retro Gamer (91). Imagine Publishing: 15. June 2011.

- ^ "Quite the classiest of mansions". The East Kent Gazette. July 28, 1993. p. 19. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

The game of the week, Day of the Tentacle (US Gold), will surely be one of the highlights of this year.

- ^ "20th Anniversary". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006.

- ^ "Games by Platform". LucasArts Entertainment Company LLC. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Hall of Fame: Guybrush Threepwood". GamesTM. The Ultimate Retro Companion (3). Imagine Publishing: 188–189. 2010. ISSN 1448-2606. OCLC 173412381.

- ^ "Sam & Max Hit the Road". GamesTM. Retro Micro Games Action. 1. Highbury Entertainment: 128–129. 2005. ISSN 1448-2606. OCLC 173412381.

- ^ Langshaw, Mark (July 22, 2010). "Retro Corner: 'Day Of The Tentacle' (PC)". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "The Greatest Games of All Time: The Only Good Tentacle Is a Green Tentacle". GameSpot. April 30, 2004. Archived from the original on November 24, 2004. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Purple Tentacle: It makes me feel great! Smarter! More aggressive! I feel like I could... like I could... like I could... TAKE ON THE WORLD!!!

- ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Bernard: Ok, you're free to go.

Green Tentacle: Thanks Bernard!

Purple Tentacle: Yes, thank you, naive human! Now I can finish taking over the world! Ha ha ha!

Green Tentacle: Wait!

Bernard: Oh, yeah. Now I remember. He's incredibly evil, isn't he?

Green Tentacle: Uh... I'll try to talk him out of it. - ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Dr. Fred: Our only hope now is to turn off my Sludge-O-Matic machine and prevent the toxic mutagen from entering the river!

Bernard: Isn't it a little late for that, Doctor?

Dr. Fred: Of course! That's why I'll have to do it... YESTERDAY! To the time machine! - ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Dr. Fred: My dials say that the larger specimen landed two hundred years in the past and the other is stuck two hundred years in the future!

Bernard: Well, hurry up and bring them back!

Dr. Fred: I will, as soon as I get a new diamond! Then all your buddies have to do is plug in their respective Chron-o-Johns and—

Bernard: Plug them in?!? Where is Hoagie going to find an electrical outlet two hundred years in the past!?!

Dr. Fred: Yes... well... He'll be needing my patented superbattery then, won't he? - ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Purple Tentacle: You can't turn off the machine if I get there first!

Laverne: Uh-oh!

Green Tentacle: Don't worry guys! This time I know I can stop him! - ^ LucasArts (June 1993). Day of the Tentacle (DOS).

Purple Tentacle: You see, I've been busy. These are all versions of myself from the future. I've been bringing them back here using the Chron-o-John. Together we will conquer the world!!

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Behind the Scenes: Maniac Mansion + Day of the Tentacle". GamesTM. The Ultimate Retro Companion (3). Imagine Publishing: 22–27. 2010. ISSN 1448-2606. OCLC 173412381.

- ^ "The Making of Day of the Tentacle". Retro Gamer. retrogamer: Imagine Publishing. December 25, 2014. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015.

- ^ Dutton, Fred (February 10, 2012). "Double Fine Adventure passes Day of the Tentacle budget". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mackey, Bob (March 7, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle: The Oral History". USgamer. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Master of Unreality: The life and times of Tim Schafer, from metal to LucasArts and Double Fine—and back to metal...". Edge. No. 204. United Kingdom: Future Publishing. August 2009. pp. 82–87.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wild, Kim (September 2010). "The Making of Day of the Tentacle". Retro Gamer (81). Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing: 84–87. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mackey, Bob (March 7, 2016). "Behind the Art of Day of the Tentacle". USgamer. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Morrison, Mike; Morrison, Sandie (October 1994). "Interactive Entertainment Today". The Magic of Interactive Entertainment. Sams. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-672-30590-0.

- ^ a b "Lights, Camera, Interaction". Computer Gaming World. No. 108. Russell Sipe. July 1993. p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Mackey, Bob (March 7, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle Composer Peter McConnell on Communicating Cartooniness". USgamer. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle for PC". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Maniac Mansion: Day of the Tentacle for PC Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Staff (August 1994). "PC Gamer Top 40: The Best Games of All Time; The Ten Best Games that Almost Made the Top 40". PC Gamer US (3): 42.

- ^ a b "Announcing The New Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World. June 1994. pp. 51–58.

- ^ a b "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Dickens, Evan (April 2, 2004). "Top 20 Adventure Games of All-Time". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ a b "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c "IGN Top 100 Games 2007: 84". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Videogame Villains – Purple Tentacle is number 82". IGN.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "PC Gamer's Top 100". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ Staff (August 2009). "Master of Unreality". Edge. No. 204. United Kingdom: Future Publishing. pp. 82–87.

- ^ Ardai, Charles (September 1993). "There's A Sucker Born Every Minute". Computer Gaming World. No. 110. pp. 46–47, 80. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014.

- ^ "Invasion Of The Data Stashers". Computer Gaming World. April 1994. pp. 20–42.

- ^ Weksler, Mike (June 1994). "CDs On A ROMpage". Computer Gaming World. pp. 36–40.

- ^ Petersen, Sandy (November 1993). "Eye of the Monitor". Dragon (199): 56–64.

- ^ LaRose, Phil (December 31, 1993). "Maniac Sequel Fights Influence of Long Arm of Purple Tentacle". The Advocate. FUN; Pg. 32.

- ^ Smith, Geoff (November 28, 1993). "COMPUTER GAMES; 'Tentacle' Grabs Your Attention". Boston Herald. LIFESTYLE; Pg. 057.

- ^ Vox Day (September 29, 1994). "Day of the Tentacle". The Blade. Pg. 16.

- ^ Wee, Lim Choon (July 29, 1993). "The Fun Continues in Maniac Mansion 2". The New Straits Times. LEISURE; Pg. 18.

- ^ Baum, Daniel (March 20, 1994). "Stop the Tentacle From Taking Over the World". The Jerusalem Post. SCIENCE; Pg. 05.

- ^ Remo, Chris (March 11, 2005). "Day of the Tentacle review". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ AG Staff (December 30, 2011). "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ "Top 10 LucasArts Adventure Games". IGN. November 17, 2009. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ "Behind the Scenes: Zombies Ate My Neighbors". GamesTM. The Ultimate Retro Companion (3). Imagine Publishing: 46. 2010. ISSN 1448-2606. OCLC 173412381.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley (June 19, 2009). "Telltale wants to make episodic Day of the Tentacle". VideoGamer.com. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- ^ Horti, Samuel (July 22, 2018). "Part one of fan-made Day of the Tentacle sequel available to download". PC Gamer. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Dietrich, Martin (July 23, 2018). "Return of the Tentacle - Kostenlose Fan-Fortsetzung des Klassikers". GameStar (in German). Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Watts, Rachel (August 2018). "Fan-made Day of the Tentacle sequel released for free". PCGamesN. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (July 23, 2018). "Fans Create Day Of The Tentacle Sequel, And It's Pretty Much Perfect". Kotaku. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (September 27, 2013). "How LucasArts Fell Apart". Kotaku. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Matulef, Jeffrey (October 23, 2015). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered debuts in-game screenshots". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Furniss, Zach (December 5, 2015). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered is coming to PS4 March 2016". Destructoid. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Neltz, Andres (March 8, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered Arrives on March 22". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ "Linux version?". Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Double Fine – Action News". www.doublefine.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "PSNProfiles". January 3, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Playstation Store". Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Makedonski, Brett (May 13, 2020). "Grim Fandango, Full Throttle, and Day of the Tentacle finally break PS4 console exclusivity this year". Destructoid. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (January 4, 2017). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered is now free on PlayStation Plus". Eurogamer. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Sarkar, Samit (December 28, 2016). "PlayStation Plus gets Day of the Tentacle Remastered and more next month". Polygon. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b McWhertor, Michael (December 8, 2014). "Tim Schafer's plans for Day of the Tentacle Remastered, revisiting more LucasArts classics". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (March 22, 2016). "The Skywalker Ranch Has A Treasure Trove Of Old LucasArts Games". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Day of the Tentacle: Remastered (pc)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Corbett, Richard (March 21, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Petty, Jared (March 21, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered Review". IGN. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Mackey, Bob (March 22, 2016). "Day of the Tentacle Remastered PC Review: Time After Time". USgamer. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

External links[edit]

- 1993 video games

- Cultural depictions of Benjamin Franklin

- Cultural depictions of George Washington

- Cultural depictions of John Hancock

- Cultural depictions of Thomas Jefferson

- DOS games

- LucasArts games

- Classic Mac OS games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- Science fiction video games

- SCUMM games

- ScummVM-supported games

- Video game sequels

- Video games about extraterrestrial life

- Video games about time travel

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games featuring female protagonists

- Video games scored by Clint Bajakian

- Video games scored by Michael Land

- Video games scored by Peter McConnell

- Video games set in the United States

- Video games with commentaries

- Xbox One games