Anti-nuclear movement in the United States

| Anti-nuclear movement |

|---|

|

| By country |

| Lists |

The anti-nuclear movement in the United States consists of more than 80 anti-nuclear groups that oppose nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and/or uranium mining. These have included the Abalone Alliance, Clamshell Alliance, Committee for Nuclear Responsibility, Nevada Desert Experience, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Plowshares Movement, United Steelworkers of America (USWA) District 31, Women Strike for Peace, Nukewatch, and Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Some fringe aspects of the anti-nuclear movement have delayed construction or halted commitments to build some new nuclear plants,[1] and have pressured the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to enforce and strengthen the safety regulations for nuclear power plants.[2] Most groups in the movement focus on nuclear weapons.

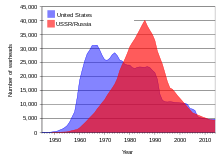

Anti-nuclear protests reached a peak in the 1970s and 1980s and grew out of the environmental movement.[3] Campaigns that captured national public attention involved the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant (by the Clamshell Alliance), Diablo Canyon Power Plant, Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant, and Three Mile Island.[1]

Beginning in the 1980s, many anti-nuclear power activists began shifting their interest, by joining the rapidly growing Nuclear Freeze campaign, and the primary concern about nuclear hazards in the US changed from the problems of nuclear power plants to the prospects of nuclear war.[4] On June 3, 1981, the White House Peace Vigil began and has continued day and night ever since, thanks to William Thomas and a small band of stalwart antinuclear activists who launched the "Proposition One Campaign for a Nuclear-Free Future"[5] voter initiative in 1993 which led to a bill that has been introduced into the House of Representatives every session by Eleanor Holmes Norton. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.[6][7] International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983, at 50 sites across the United States.[8][9] There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.[10][11]

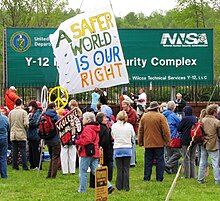

More recent campaigning by anti-nuclear groups has related to several nuclear power plants including the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant,[12][13] Indian Point Energy Center,[14] Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station,[15] Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station,[16] Salem Nuclear Power Plant,[17] and Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant.[18] There have also been campaigns relating to the Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Plant,[19] the Idaho National Laboratory,[20] Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository proposal,[21] the Hanford Site, the Nevada Test Site,[22] Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,[23] and transportation of nuclear waste from the Los Alamos National Laboratory.[24]

Some scientists and engineers have expressed safety concerns about specific nuclear power plants, including: Barry Commoner, S. David Freeman, John Gofman, Arnold Gundersen, Mark Z. Jacobson, Amory Lovins, Arjun Makhijani, Gregory Minor, M.V. Ramana, Joseph Romm and Benjamin K. Sovacool. Scientists who have opposed nuclear weapons include Paul M. Doty, Hermann Joseph Muller, Linus Pauling, Eugene Rabinowitch, M.V. Ramana and Frank N. von Hippel.

Emergence of the movement[edit]

Emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement[edit]

On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.[25]

The nuclear debate initially was about nuclear weapons policy, and began within the scientific community. Scientific concern about the adverse health effects arising from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing first emerged in 1954.[26] Professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs were involved.[27] The National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy was formed in November 1957, and surveys showed rising public uneasiness about the nuclear arms race—especially atmospheric nuclear weapons tests that sent radioactive fallout around the globe.[28] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread throughout the United States.[27]

Between 1945 and 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous nuclear weapons testing. A total of 1,054 nuclear tests and two nuclear attacks were conducted, with over 900 of them at the Nevada Test Site, and ten on miscellaneous sites in the United States (Alaska, Colorado, Mississippi, and New Mexico).[29] Until November 1962, the vast majority of the U.S. tests were above-ground; after the acceptance of the Partial Test Ban Treaty all testing was relegated underground, in order to prevent the dispersion of nuclear fallout.

The U.S. program of atmospheric nuclear testing exposed some people to the hazards of fallout. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[30][31]

Emergence of the anti-nuclear power movement[edit]

Unexpectedly high costs in the nuclear weapons program, along with competition with the Soviet Union and a desire to spread democracy through the world, created pressure on federal officials to develop a civilian nuclear power industry that could help justify the government's considerable expenditures."[32]

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954 encouraged private corporations to build nuclear reactors and a significant learning phase followed with many early partial core meltdowns and accidents at experimental reactors and research facilities.[33] This led to the introduction of the Price-Anderson Act in 1957, which was, "an implicit admission that nuclear power provided risks that producers were unwilling to assume without federal backing."[33] The Price-Anderson Act "shields nuclear utilities, vendors and suppliers against liability claims in the event of a catastrophic accident by imposing an upper limit on private sector liability." Without such protection, private companies were unwilling to become involved. No other technology in the history of American industry has enjoyed such continuing blanket protection.[32]

The first U.S. reactor to face public opposition was Fermi 1 in 1957. It was built approximately 30 miles from Detroit and there was opposition from the United Auto Workers Union.[34]

Pacific Gas & Electric planned to build the first commercially viable nuclear power plant in the US at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco. The proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958.[35] The proposed plant site was close to the San Andreas fault and the region's environmentally sensitive fishing and dairy industries. The Sierra Club became actively involved in the controversy.[36] The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the Bodega Bay power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement in the United States to the controversy over Bodega Bay.[35] Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.[35]

A small military test reactor exploded at the Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One in Idaho Falls in January 1961, causing 3 fatalities.[37] This was caused by a combination of dangerous reactor design plus either sabotage, operator error by experienced operators.[38] A further partial meltdown at the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station in Michigan in 1966.[33]

In his 1963 book Change, Hope and the Bomb, David E. Lilienthal criticized nuclear developments, particularly the nuclear industry's failure to address the nuclear waste question. He argued that it would be "particularly irresponsible to go ahead with the construction of full scale nuclear power plants without a safe method of nuclear waste disposal having been demonstrated." However, Lilienthal stopped short of a blanket rejection of nuclear power. His view was that a more cautious approach was necessary.[39]

Samuel Walker, in his book Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, explains that the growth of the nuclear industry in the U.S. occurred as the environmental movement was being formed. Environmentalists saw the advantages of nuclear power in reducing air pollution, but became critical of nuclear technology on other grounds.[40] The view that nuclear power was better for the environment than conventional fuels was partially undermined in the late 1960s when major controversy erupted over the effects of waste heat from nuclear plants on water quality. The nuclear industry "gradually and reluctantly took action to reduce thermal pollution by building cooling towers or ponds for plants on inland waterways."[40]

Several authors challenged the prevailing view that the small amounts of radioactivity released by nuclear power plants during normal operation were not a problem. They argued "that the routine releases were a severe threat to public health and could cause tens of thousands of deaths from cancer each year."[40] Exchange of views about radiation risks caused uneasiness about nuclear power, especially among those unable to evaluate the conflicting claims.[40]

The large size of nuclear plants ordered during the late 1960s raised new safety questions and created fears of a severe reactor accident that would send large quantities of radioactivity into the environment. In the early 1970s, a highly contentious debate over the performance of emergency core cooling systems in nuclear plants, designed to prevent a core meltdown that could lead to the "China syndrome", received coverage in the popular media and technical journals.[18][41] The emergency core cooling systems controversy opened up whether the AECs first priority was promotion of the nuclear industry or protection of public health and safety.[42]

By the early 1970s, anti-nuclear activity had increased dramatically in conjunction with concerns about nuclear safety and criticisms of a policy-making process that allowed little voice for these concerns. Initially scattered and organized at the local level, opposition to nuclear power became a national movement by the mid-1970s when such groups as the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, Natural Resources Defense Council, Union of Concerned Scientists, and Critical Mass became involved.[43] With the rise of environmentalism in the 1970s, the anti-nuclear movement grew substantially:[42]

In 1975–76, ballot initiatives to control or halt the growth of nuclear power were introduced in eight western states. Although they enjoyed little success at the polls, the controls they sought to impose were sometimes adopted in part by state legislature, most notably in California. Interventions in plant licensing proceedings increased, often focusing on technical issues related to safety. This widespread popular ferment kept the issue before the public and contributed to growing public skepticism about nuclear power.[42]

Another major area of ongoing concern was nuclear waste management. The absence of a working waste management facility became an important issue by the mid-1970s:

In 1976, the California Energy Commission announced that it would not approve any more nuclear plants unless the utilities could specify fuel and waste disposal costs, an impossible task without decision on reprocessing, spent fuel storage and waste disposal. By the late 1970s, over thirty states had passed legislation regulating various activities associated with nuclear waste.[44]

Many technologies and materials associated with the creation of a nuclear power program have a dual-use capability, in that they can be used to make nuclear weapons if a country chooses to do so.[45] In 1975 over 2,000 prominent scientists signed a Declaration on Nuclear Power, prepared by the Union of Concerned Scientists, warning of the dangers of nuclear proliferation and urging the President and Congress to suspend the exportation of nuclear power to other countries, and reduce domestic construction until major problems were resolved.[46] Theodore Taylor, a former nuclear weapons designer, explained, "the ease with which nuclear bombs could be manufactured if fissionable material was available."[41]

In 1976, four nuclear engineers -three from GE and one from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission- resigned, stating that nuclear power was not as safe as their superiors were claiming.[47][48] These men were engineers who had spent most of their working life building reactors, and their defection galvanized anti-nuclear groups across the country.[49][50] They testified to the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy that:

the cumulative effect of all design defects and deficiencies in the design, construction and operations of nuclear power plants makes a nuclear power plant accident, in our opinion, a certain event. The only question is when, and where.[47]

These issues, together with a series of other environmental, technical, and public health questions, made nuclear power the source of acute controversy. Public support, which was strong in the early 1960s, had been shaken. Forbes, in the September 1975 issue, reported that "the anti-nuclear coalition has been remarkably successful ... [and] has certainly slowed the expansion of nuclear power."[18] By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism, fueled by dissenting experts, had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence. Although it lacked a single coordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, it emerged as a movement sharply focused on opposing nuclear power, and the movement's efforts gained a great deal of national attention.[18]

On March 28, 1979, equipment failures and operator error contributed to loss of coolant and a partial core meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant in Pennsylvania. The World Nuclear Association has stated that cleanup of the damaged nuclear reactor system at TMI-2 took nearly 12 years and cost approximately US$973 million.[51] Benjamin K. Sovacool, in his 2007 preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, estimated that the TMI accident caused a total of $2.4 billion in property damages.[33] The health effects of the Three Mile Island accident are widely, but not universally, agreed to be very low level.[51][52] The accident triggered protests around the world.[53]

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident inspired Perrow's book Normal Accidents, where a nuclear accident occurs, resulting from an unanticipated interaction of multiple failures in a complex system. TMI was an example of a normal accident because it was "unexpected, incomprehensible, uncontrollable and unavoidable."[54]

Perrow concluded that the failure at Three Mile Island was a consequence of the system's immense complexity. Such modern high-risk systems, he realized, were prone to failures however well they were managed. It was inevitable that they would eventually suffer what he termed a 'normal accident'. Therefore, he suggested, we might do better to contemplate a radical redesign, or if that was not possible, to abandon such technology entirely.[55]

Nuclear power plants are a complex energy system.[56][57][39] and opponents of nuclear power have criticized the sophistication and complexity of the technology. Helen Caldicott has said: "in essence, a nuclear reactor is just a very sophisticated and dangerous way to boil water – analogous to cutting a pound of butter with a chain saw."[58] These critics of nuclear power advocate the use of energy conservation, efficient energy use, and appropriate renewable energy technologies to create our energy future.[59] Amory Lovins, from the Rocky Mountain Institute, has argued that centralized electricity systems with giant power plants are becoming obsolete. In their place are emerging "distributed resources"—smaller, decentralized electricity supply sources (including efficiency) that are cheaper, cleaner, less risky, more flexible, and quicker to deploy. Such technologies are often called "soft energy technologies" and Lovins viewed their impacts as more gentle, pleasant, and manageable than hard energy technologies such as nuclear power.[60]

Nuclear energy systems have a long stay time. The completion of the sequence of activities related to one commercial nuclear power station, from the start of construction through the safe disposal of its last radioactive waste, may take 100–150 years.[56]

Emergence of the anti-uranium movement[edit]

Uranium mining is the process of extraction of uranium ore from the ground. A prominent use of uranium from mining is as fuel for nuclear power plants. After mining uranium ores, they are normally processed by grinding the ore materials to a uniform particle size and then treating the ore to extract the uranium by chemical leaching. The milling process commonly yields dry powder-form material consisting of natural uranium, "yellowcake", which is sold on the uranium market as U3O8, and uranium mining can use large amounts of water.

The Church Rock uranium mill spill occurred in New Mexico on July 16, 1979, when United Nuclear Corporation's Church Rock uranium mill tailings disposal pond breached its dam.[61][62] Over 1,000 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and 93 million gallons of acidic, radioactive tailings solution flowed into the Puerco River, and contaminants traveled 80 miles (130 km) downstream to Navajo County, Arizona and onto the Navajo Nation.[61] The accident released more radioactivity than the Three Mile Island accident that occurred four months earlier and was the largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history.[61][63][64][65] Groundwater near the spill was contaminated and the Puerco rendered unusable by local residents, who were not immediately aware of the toxic danger.[66]

Despite efforts made in cleaning up uranium sites, significant problems stemming from the legacy of uranium development still exist today on the Navajo Nation and in the states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. Hundreds of abandoned mines have not been cleaned up and present environmental and health risks in many communities.[67] The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that there are 4000 mines with documented uranium production, and another 15,000 locations with uranium occurrences in 14 western states,[68] most found in the Four Corners area and Wyoming.[69] The Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act is a United States environmental law that amended the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 and gave the Environmental Protection Agency the authority to establish health and environmental standards for the stabilization, restoration, and disposal of uranium mill waste.[70]

Anti-uranium activists in the US include: Thomas Banyacya, Manuel Pino and Floyd Red Crow Westerman.

Specific groups[edit]

Anti-nuclear organizations oppose nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and/or uranium mining. More than eighty anti-nuclear groups operate, or have operated, in the United States. These include:

- Abalone Alliance

- Arms Control Association

- Bailly Alliance

- Beyond Nuclear

- Clamshell Alliance

- Committee for Nuclear Responsibility

- Corporate Accountability International

- Council for a Livable World

- Critical Mass

- Friends of the Earth

- Greenpeace USA

- Mothers for Peace

- Musicians United for Safe Energy

- NAU Against Uranium

- Nevada Desert Experience

- No Nukes group

- Nuclear Age Peace Foundation

- Nuclear Control Institute

- Nuclear Information and Resource Service

- Peace Action

- Physicians for Social Responsibility

- Plowshares Movement

- Public Citizen

- The Seneca Women's Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice

- Shad Alliance

- Sierra Club

- Three Mile Island Alert

- Women Strike for Peace

Some of the most influential groups in the anti-nuclear movement have had some members who were elite scientists, including Nobel Laureates Linus Pauling and Hermann Joseph Muller. In the United States, these scientists have belonged primarily to three groups: the Union of Concerned Scientists, the Federation of American Scientists, and the Committee for Nuclear Responsibility.[71]

Many American religious organizations have a long record of opposing nuclear weapons. Rejecting the development and use of nuclear weapons is "one of the most widely shared convictions across faith traditions".[72] In the 1980s religious groups organized large anti-nuclear protests involving hundreds of thousands of people, and specific groups involved included the Southern Baptist Convention, and the Episcopal Church. The Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish communities published explicitly anti-nuclear statements, and in 2000 Muslims also began to take a stance against nuclear weaponry.[72]

The platform adopted by the delegates of the Green Party at their annual Green Congress May 26–28, 2000, reflecting the majority views of the membership, included the creation of self-reproducing, renewable energy systems and use of federal investments, purchasing, mandates, and incentives to shut down nuclear power plants and phase out fossil fuels.[73]

Recent campaigning by anti-nuclear groups has related to several nuclear power plants including the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant,[12][13] Indian Point Energy Center,[14] Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station,[15] Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station,[16] Salem Nuclear Power Plant,[17] and Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant.[18] There have also been campaigns relating to the Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Plant,[19] the Idaho National Laboratory,[20] proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository,[21] the Hanford Site, the Nevada Test Site,[22] Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,[23] and transportation of nuclear waste from the Los Alamos National Laboratory.[24]

Anti-nuclear protests[edit]

On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.[25][74]

There were many anti-nuclear protests in the United States which captured national public attention during the 1970s and 1980s. These included the well-known Clamshell Alliance protests at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant and the Abalone Alliance protests at Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, where thousands of protesters were arrested. Other large protests followed the 1979 Three Mile Island accident.[1]

A large anti-nuclear demonstration was held in May 1979 in Washington, D.C., when 65,000 people including the Governor of California, attended a march and rally against nuclear power.[75] In New York City on September 23, 1979, almost 200,000 people attended a protest against nuclear power.[76] Anti-nuclear power protests preceded the shutdown of the Shoreham, Yankee Rowe, Millstone I, Rancho Seco, Maine Yankee, and about a dozen other nuclear power plants.[77]

On June 3, 1981, Thomas launched the White House Peace Vigil in Washington, D.C.[78] He was later joined on the vigil by anti-nuclear activists Concepcion Picciotto and Ellen Benjamin.[79]

On June 6, 1982, a crowd of 85,000 gathers at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, CA for "Peace Sunday: We Have a Dream" a rally and concert in support of the United Nations Special Session on Nuclear Disarmament. Performers include Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder and Crosby, Stills & Nash.

On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history.[6][7] International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983, at 50 sites across the United States.[8][9] In 1986, hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament.[80] There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.[10][11]

In the 1980s, when fewer nuclear power plants remained in the construction and licensing pipeline, and interest in energy policy as a national issue declined, many anti-nuclear activists switched their focus to nuclear weapons and the arms race.[81] There has also been an institutionalization of the anti-nuclear movement,[82] where the anti-nuclear movement carried its contests into less visible, and more specialized institutional areas, such as regulatory and licensing hearings, and legal challenges.[82] At the state level, anti-nuclear groups were also successful in placing several anti-nuclear referendums on the ballot.[3]

On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[83][84] This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades.[85] In 2008, 2009, and 2010, there have been protests about, and campaigns against, several new nuclear reactor proposals in the United States.[86][87]

There is an annual protest against U.S. nuclear weapons research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California and in the 2007 protest, 64 people were arrested.[88] There have been a series of protests at the Nevada Test Site and in the April 2007 Nevada Desert Experience protest, 39 people were cited by police.[89] There have been anti-nuclear protests at Naval Base Kitsap for many years, and several in 2008.[90][91][92] Also in 2008 and 2009, there have been protests about several proposed nuclear reactors.[93][86]

People with anti-nuclear views[edit]

Al Gore[edit]

Former vice president Al Gore says he is not anti-nuclear, but has stated that the "cost of the present generation of reactors is nearly prohibitive."[94] In his 2009 book, Our Choice, Gore argues that nuclear power was once "expected to provide virtually unlimited supplies of low-cost electricity", but the reality is that it has been "an energy source in crisis for the last 30 years."[95] Worldwide growth in nuclear power has slowed in recent years, with no new reactors and an "actual decline in global capacity and output in 2008." In the United States, "no nuclear power plants ordered after 1972 have been built to completion."[95]

Of the 253 nuclear power reactors originally ordered in the United States from 1953 to 2008, 48 percent were canceled, 11 percent were prematurely shut down, 14 percent experienced at least a one-year-or-more outage, and 27 percent are operating without having a year-plus outage. Thus, only about one fourth of those ordered, or about half of those completed, are still operating and have proved relatively reliable.[96]

Amory Lovins[edit]

In his 2005 book Winning the Oil Endgame, Amory Lovins praises nuclear power engineers, but is critical of the nuclear industry:

No vendor has made money selling power reactors. This is the greatest failure of any enterprise in the industrial history of the world. We don't mean that as a criticism of nuclear power's practitioners, on whose skill and devotion we all continue to depend; the impressive operational improvements in U.S. power reactors in recent years deserve great credit. It is simply how technologies and markets evolved, despite the best intentions and immense effort. In nuclear power's heyday, its proponents saw no competitors but central coal-fired power stations. Then, in quick succession, came end-use efficiency, combined-cycle plants, distributed generation (including versions that recovered valuable heat previously wasted), and competitive windpower. The range of competitors will only continue to expand more and their costs to fall faster than any nuclear technology can match.[97]

In 1988, Lovins argued that improving energy efficiency can simultaneously ameliorate greenhouse warming, reduce acid rain and air pollution, save money, and avoid the problems of nuclear power. Given the urgency of abating global warming, Lovins stated that we cannot afford to invest in nuclear power when those same dollars put into efficiency would displace far more carbon dioxide.[98]

In "Nuclear Power: Climate Fix or Folly," published in 2010, Lovins argued that expanded nuclear power "does not represent a cost-effective solution to global warming and that investors would shun it were it not for generous government subsidies lubricated by intensive lobbying efforts."[99]

Joseph Romm[edit]

Joseph Romm contends that nuclear power generates about 20 percent of all U.S. electricity, and is a low-carbon source of around-the-clock power, which has received renewed interest in recent years.[100] Yet, Romm says, nuclear power's "own myriad limitations will constrain its growth, especially in the near term", and the limitations include:[100]

- "Prohibitively high, and escalating, capital costs

- Production bottlenecks in key components needed to build plants

- Very long construction times

- Concerns about uranium supplies and importation issues

- Unresolved problems with availability and security of radioactive waste storage, which has a 100,000 year shelf life

- Large-scale water use and contamination amid shortages

- High electricity prices from new plants".[100]

Randall Forsberg[edit]

Randall Forsberg (née Watson, 1943–2007) became interested in arms control issues while working at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1974, she returned to the United States, and became a graduate student in international studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1979, Forsberg wrote Call to Halt the Arms Race, which later was the manifesto of the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign. The document advocated a bilateral halt to the testing, production, deployment and delivery of nuclear weapons.[101]

Forsberg was awarded a doctorate in 1980 and she started the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies, which became an important resource for the peace movement and anti-nuclear weapons movement. In 1983 Forsberg was awarded a MacArthur Foundation genius grant. In 2005 she became Spitzer Professorship in Political Science at the City College of New York, and died of cancer in 2007 when she was 64 years old.[101]

Christopher Flavin[edit]

Many advocates of nuclear power argue that, given the urgency of doing something about climate change quickly, it must be pursued. Christopher Flavin, however, contends that speedy implementation is not one of nuclear power's strong points:[102]

Planning, licensing, and constructing even a single nuclear plant typically takes a decade or more, and plants frequently fail to meet completion deadlines. Due to the dearth of orders in recent decades, the world currently has very limited capacity to manufacture many of the critical components of nuclear plants. Rebuilding that capacity will take a decade or more.[102]

Given the urgency of the climate problem, Flavin emphasizes the rapid commercialization of renewable energy and efficient energy use:

Improved energy productivity and renewable energy are both available in abundance—and new policies and technologies are rapidly making them more economically competitive with fossil fuels. In combination, these energy options represent the most robust alternative to the current energy system, capable of providing the diverse array of energy services that a modern economy requires. Given the urgency of the climate problem, that is indeed convenient.[103]

Other people[edit]

Selected other notable individuals who have expressed reservations about nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and/or uranium mining in the US include:[104][105][106]

- Larry Bogart

- Helen Caldicott

- Barry Commoner

- Frances Crowe

- Carrie Barefoot Dickerson

- Paul M. Doty

- Jane Fonda

- Randall Forsberg

- Paul Gunter

- John Hall

- Jackie Hudson

- Sam Lovejoy

- Amory Lovins

- Arjun Makhijani

- Gregory Minor

- Hermann Joseph Muller

- Ralph Nader

- Linus Pauling

- Eugene Rabinowitch

- Bonnie Raitt

- Martin Sheen

- Karen Silkwood

- Thomas

- Louie Vitale

- Harvey Wasserman

Criticism[edit]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: poor referencing and sloppy referencing format; some newer scholarly sources and improved copyediting would also help. (July 2016) |

In November 2009, The Washington Post reported that nuclear power is emerging as "perhaps the world's most unlikely weapon against climate change, with the backing of even some green activists who once campaigned against it."[94] The article said that rather than deride the potential for nuclear power, some environmentalists are embracing it, and that presently there is only "muted opposition"—nothing like the protests and plant invasions that helped define the anti-nuclear movement in the United States during the 1970s.[94]

Patrick Moore, one of the initial founders of Greenpeace, said in a 2008 interview that, "It wasn't until after I'd left Greenpeace and the climate change issue started coming to the forefront that I started rethinking energy policy in general and realized that I had been incorrect in my analysis of nuclear as being some kind of evil plot."[108] Bernard Cohen, Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Pittsburgh, calculates that nuclear power is many times safer than any other form of power generation.[109]

Critics of the movement point to independent studies showing the capital costs of renewable energy sources are higher than those from nuclear power.[110]

Critics argue that the amount of waste generated by nuclear power is very small, as all the high-level nuclear waste from 50+ years of operation of the world's nuclear reactors would fit into a single football field to the depth of five feet.[111] Furthermore, U.S. coal power plants presently create nearly a million tons of low-level radioactive waste per day and therefore release more total radioactivity than the nation's nuclear plants,[112] due to the uranium and thorium found naturally within the coal. Nuclear proponents also point out that cost and the quantity of waste figures for the operation of nuclear power plants are commonly derived from nuclear reactors built using second generation designs, dating from the 1960s. Advanced reactor designs are estimated to be even cheaper to operate and generate less than 1% the amount of waste of current designs, like Integral Fast Reactors or Pebble Bed Reactors.[citation needed]

It is because of these facts that proponents argue that nuclear fission power is the safest means currently available to entirely replace the use of fossil fuels, and pro-nuclear environmentalists argue that a combination of both nuclear energy and renewable energy would be the fastest, safest, and cheapest way forward.[113]

In 2007 Gwyneth Cravens outlined the message of her newest book, Power to Save the World: The Truth About Nuclear Energy. It argues for nuclear power as a safe energy source and an essential preventive of global warming. Pandora's Promise is a 2013 documentary film, directed by Robert Stone. It presents an argument that nuclear energy, typically feared by environmentalists, is in fact the only feasible way of meeting humanity's growing need for energy while also addressing the serious problem of climate change. The movie features several notable individuals (some of whom were once vehemently opposed to nuclear power, but who now speak in support of it), including: Stewart Brand, Gwyneth Cravens, Mark Lynas, Richard Rhodes and Michael Shellenberger.[114] Anti-nuclear advocate Helen Caldicott appears briefly.[115]

As of 2014, the U.S. nuclear industry has begun a new lobbying effort, hiring three former senators—Evan Bayh, a Democrat; Judd Gregg, a Republican; and Spencer Abraham, a Republican—as well as William M. Daley, a former staffer to President Obama. The initiative is called Nuclear Matters, and it has begun a newspaper advertising campaign.[116]

Recent developments[edit]

As of early 2010, anti-nuclear groups such as Physicians for Social Responsibility, NukeFree.org, and NIRS were actively fighting federal loan guarantees for new nuclear plant construction. In February 2010, several groups coordinated a national call-in day to Congress to attempt to stop $54 billion in federal loan guarantees for new nuclear plants. However, the first such loan guarantee of $8.3 billion was offered to Southern Company that same month.[117]

In January 2010, about 175 anti-nuclear activists participated in a 126-mile walk in an effort to block the re-licensing of Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant.[118] In February 2010, numerous anti-nuclear activists and private citizens gathered in Montpelier, to be at hand as the Vermont Senate voted 26 to 4 against the "Public Good" certificate needed for continued operation of Vermont Yankee past 2012.[119]

In April 2010 a dozen environmental groups (including Friends of the Earth, South Carolina's Sierra Club, Nuclear Watch South, the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, Georgia Women's Action for New Directions) stated that the proposed AP1000 reactor containment design is "inherently less safe than current reactors."[120] Arnold Gundersen, a nuclear engineer, authored a 32-page report arguing that the new AP1000 reactors will be vulnerable to leaks caused by corrosion holes. There are plans to construct the Westinghouse AP1000 reactors at seven sites across the southeast, including Plant Vogtle in Burke County, Georgia.[120][121]

In October 2010, Michael Mariotte, executive director of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service anti-nuclear group, predicted that the U.S. nuclear industry will not experience a nuclear renaissance, for the most simple of reasons: "nuclear reactors make no economic sense". The economic slump has driven down electricity demand and the price of competing energy sources, and Congress has failed to pass climate change legislation, making nuclear economics very difficult.[122]

When Peter Shumlin was Governor of Vermont, he was a prominent opponent of the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant and two days after Shumlin was elected in November 2010, Entergy put the plant up for sale.[123]

Post-Fukushima[edit]

Following the 2011 Japanese nuclear accidents, activists who were involved in the movement's emergence (such as Graham Nash and Paul Gunter), suggest that Japan's nuclear crisis may rekindle an anti-nuclear protest movement in the United States. The aim, they say, is "not just to block the Obama administration's push for new nuclear construction, but to convince Americans that existing plants pose dangers."[126]

In March 2011, 600 people gathered for a weekend protest outside the Vermont Yankee plant. The demonstration was held to show support for the thousands of Japanese people who are endangered by possible radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[127]

In April 2011, Rochelle Becker, executive director of the Alliance for Nuclear Responsibility said that the United States should review its nuclear accident liability limits, in the light of the economic impacts of the Fukushima disaster.[128]

The New England region has a long history of anti-nuclear activism and 75 people held a State House rally on April 6, 2011, to "protest the region's aging nuclear plants and the increasing stockpile of radioactive spent fuel rods at them."[129] The protest was held shortly before a State House hearing where legislators were scheduled to hear representatives of the region's three nuclear plants – Pilgrim in Plymouth, Vermont Yankee in Vernon, and Seabrook in New Hampshire—talk about the safety of their reactors in the light of the Japanese nuclear crisis. Vermont Yankee and Pilgrim have reactor designs similar to the crippled Japanese nuclear plants.[129]

As of April 2011, a total of 45 groups and individuals from across the nation are formally asking the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to immediately suspend all licensing and other activities at 21 proposed nuclear reactor projects in 15 states until the NRC completes a thorough post-Fukushima reactor crisis examination. The petitioners also are asking the NRC to supplement its own investigation by establishing an independent commission comparable to that set up in the wake of the serious, though less severe, 1979 Three Mile Island accident. The petitioners include Public Citizen, Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, and San Luis Obispo Mothers for Peace.[130][131][132]

Thirty two years after the No Nukes concert in New York, on August 7, 2011, a Musicians United for Safe Energy benefit concert was held Mountain View, California, to raise money for MUSE and for Japanese tsunami/nuclear disaster relief. The show was powered off-grid and artists included Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, John Hall, Graham Nash, David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Kitaro, Jason Mraz, Sweet Honey and the Rock, the Doobie Brothers, Tom Morello, and Jonathan Wilson.

In February 2012, the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved the construction of two additional reactors at the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, the first reactors to be approved in over 30 years since the Three Mile Island accident,[133] but NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko cast a dissenting vote citing safety concerns stemming from Japan's 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, and saying "I cannot support issuing this license as if Fukushima never happened".[134] One week after Southern received the license to begin major construction on the two new reactors, a dozen environmental and anti-nuclear groups are suing to stop the Plant Vogtle expansion project, saying "public safety and environmental problems since Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor accident have not been taken into account".[135]

The nuclear reactors to be built at Vogtle are new AP1000 third generation reactors, which are said to have safety improvements over older power reactors.[133] However, John Ma, a senior structural engineer at the NRC, is concerned that some parts of the AP1000 steel skin are so brittle that the "impact energy" from a plane strike or storm driven projectile could shatter the wall.[136] Edwin Lyman, a senior staff scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is concerned about the strength of the steel containment vessel and the concrete shield building around the AP1000.[136] Arnold Gundersen, a nuclear engineer commissioned by several anti-nuclear groups, released a report which explored a hazard associated with the possible rusting through of the steel liner of the containment structure.[121]

In March 2012, activists protested at San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station to mark the one-year anniversary of the nuclear meltdowns in Fukushima, Japan. Around 200 people rallied in San Onofre State Beach to listen to several speakers, including two Japanese residents who lived through the Fukushima meltdowns. Residents Organizing for Safe Environment and several other anti-nuclear energy organizations, organized the event and about 100 activists came in from San Diego.[137]

As of March 2012, 23 aging nuclear power plants continue to operate, including some similar in design to those that melted down in Fukushima, such as Vermont Yankee, and Indian Point 2 just 24 miles north of New York City. Vermont Yankee has reached the end of its projected lifetime operation but, despite strong local opposition, the NRC favored extending its license; however, on August 27, 2013, Entergy (VT Yankee's owner) announced it was decommissioning the plant and that "The station is expected to cease power production after its current fuel cycle and move to safe shutdown in the fourth quarter of 2014."[138] On March 22, 2012, "more than 1,000 people marched to the plant in protest, and about 130 engaging in civil disobedience were arrested".[139]

According to a 2012 Pew Research Center poll, 44 percent of Americans favor and 49 percent oppose the promotion of increased use of nuclear power, while 69 percent favor increasing federal funding for research on wind power, solar power, and hydrogen energy technology.[139][140]

In 2013, four aging, uncompetitive, reactors were permanently closed: San Onofre 2 and 3 in California, Crystal River 3 in Florida, and Kewaunee in Wisconsin.[141][142] Vermont Yankee closed in 2014. New York State has closed Indian Point Energy Center, in Buchanan, 30 miles from New York City.[142]

With reference to the pro-nuclear film Pandora's Promise, economics professor, John Quiggin, comments that it presents the environmental rationale for nuclear power, but that reviving nuclear power debates is a distraction, and the main problem with the nuclear option is that it is not economically viable. Quiggin says that we need more efficient energy use and more renewable energy commercialization.[143]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements p. 44.

- ^ Brown & Brutoco 1997, p. 198.

- ^ a b Kitschelt, Herbert P. (January 1986). "Political Opportunity Structures and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies". British Journal of Political Science. 16 (1): 57–85. doi:10.1017/S000712340000380X. S2CID 154479502.

- ^ Lynch, Lisa (June 1, 2012). "'We Don't Wanna Be Radiated': Documentary Film and the Evolving Rhetoric of Nuclear Energy Activism" (PDF). American Literature. 84 (2): 327–351. doi:10.1215/00029831-1587368.

- ^ "Let's End the Whole Nuclear Era". Proposition 1 Campaign. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Jonathan Schell. The Spirit of June 12 Archived May 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The Nation, July 2, 2007.

- ^ a b 1982 – a million people march in New York City Archived June 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Harvey Klehr. Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today Transaction Publishers, 1988, p. 150.

- ^ a b 1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested Miami Herald, June 21, 1983.

- ^ a b Lindsey, Robert (February 6, 1987). "438 PROTESTERS ARE ARRESTED AT NEVADA NUCLEAR TEST SITE". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "493 Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site". The New York Times. The Associated Press. April 20, 1992.

- ^ a b Slat, Charles. "Groups petition against new nuclear plant". Monroe News. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Fermi 3 opposition takes legal action to block new nuclear reactor Archived March 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Hudson River Lovers Fight to Shutter Aging Nuclear Power Plant". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Oyster Creek's time is up, residents tell board Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Examiner, June 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Pilgrim Watch (undated). Pilgrim Watch

- ^ a b Unplugsalem.org (undated). UNPLUG Salem Archived September 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Stop the Bombs! April 2010 Action Event at Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Complex Archived October 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ a b Keep Yellowstone Nuclear Free (2003). Keep Yellowstone Nuclear Free Archived November 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Sierra Club. (undated). Deadly Nuclear Waste Transport Archived March 8, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b 22 Arrested in Nuclear Protest The New York Times, August 10, 1989.

- ^ a b Hundreds Protest at Livermore Lab Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The TriValley Herald, August 11, 2003.

- ^ a b Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (undated). About CCNS

- ^ a b Woo, Elaine (January 30, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson dies at 94; organizer of women's disarmament protesters". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Rüdig 1990, p. 55.

- ^ a b Brown & Brutoco 1997, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Lawrence S. Wittner. Preserving the Golden Rule as a Piece of Anti-Nuclear History Archived February 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine History News Network, February 8, 2010.

- ^ Carey Sublette, Gallery of U.S. Nuclear Tests

- ^ What governments offer to victims of nuclear tests The Associated Press, March 24, 2009.

- ^ "Radiation Exposure Compensation System: Claims to Date" (PDF). usdoj.gov.

- ^ a b John Byrne and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers, p. 136.

- ^ a b c d Sovacool, Benjamin K. (May 2008). "The costs of failure: A preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, 1907–2007". Energy Policy. 36 (5): 1802–1820. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.01.040.

- ^ Michael D. Mehta (2005). Risky business: nuclear power and public protest in Canada Lexington Books, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Paula Garb. Review of Critical Masses Archived June 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Political Ecology, Vol 6, 1999.

- ^ Thomas Raymond Wellock (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 27–28.

- ^ McKeown, William (2003). Idaho Falls: The Untold Story of America's First Nuclear Accident. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-562-4.

- ^ Hathaway, William (2006). Idaho Falls. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0738548708.

- ^ a b Rüdig 1990, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press), p. 10

- ^ a b Rüdig 1990, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c John Byrne and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers, p. 144.

- ^ John Byrne and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers, p. 205.

- ^ John Byrne and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers, p. 219.

- ^ Steven E. Miller & Scott D. Sagan (Fall 2009). "Nuclear power without nuclear proliferation?". Dædalus. 138 (4): 7–18. doi:10.1162/daed.2009.138.4.7. S2CID 57568427.

- ^ Ann Morrissett Davidon (December 1979). "The U.S. Anti-nuclear Movement". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^ a b Mark Hertsgaard (1983). Nuclear Inc. The Men and Money Behind Nuclear Energy, Pantheon Books, New York, p. 72.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 95.

- ^ "The San Jose Three". Time. February 16, 1976.

- ^ "The Struggle over Nuclear Power". Time. March 18, 1976. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ^ a b World Nuclear Association. Three Mile Island Accident Archived February 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine January 2010.

- ^ Mangano, Joseph (September 2004). "Three Mile Island: Health Study Meltdown". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 60 (5): 30–35. doi:10.2968/060005010. S2CID 143984619. Gale A122104566.

- ^ Mark Hertsgaard (1983). Nuclear Inc. The Men and Money Behind Nuclear Energy, Pantheon Books, New York, p. 95 & 97.

- ^ Perrow, C. (1982), 'The President's Commission and the Normal Accident', in Sils, D., Wolf, C. and Shelanski, V. (Eds), Accident at Three Mile Island: The Human Dimensions, Westview, Boulder, pp.173–184.

- ^ Pidgeon, N. (2011). "In retrospect: Normal Accidents". Nature. 477 (7365): 404–405. Bibcode:2011Natur.477..404P. doi:10.1038/477404a.

- ^ a b Storm van Leeuwen, Jan (2008). Nuclear power – the energy balance

- ^ Rüdig 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Helen Caldicott (2006). Nuclear Power is Not the Answer to Global Warming Or Anything Else, Melbourne University Press, ISBN 0-522-85251-3, p.xvii

- ^ Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (undated). Why Nuclear is Risky Archived March 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amory B. Lovins (1977). Soft Energy Paths: Toward a Durable Peace, Penguin Books.

- ^ a b c d Pasternak, Judy (2010). Yellow Dirt: A Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed. Free Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1416594826.

- ^ "Navajos mark 20th anniversary of Church Rock spill", The Daily Courier, Prescott, Arizona, July 18, 1999

- ^ US Congress, House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment. Mill Tailings Dam Break at Church Rock, New Mexico, 96th Cong, 1st Sess (October 22, 1979):19–24.

- ^ Brugge, D.; DeLemos, J.L.; Bui, C. (2007), "The Sequoyah Corporation Fuels Release and the Church Rock Spill: Unpublicized Nuclear Releases in American Indian Communities", American Journal of Public Health, 97 (9): 1595–600, doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.103044, PMC 1963288, PMID 17666688

- ^ Quinones, Manuel (December 13, 2011), "As Cold War abuses linger, Navajo Nation faces new mining push", E&E News, retrieved December 28, 2012

- ^ Pasternak 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Pasternak, Judy (November 19, 2006). "A peril that dwelt among the Navajos". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Uranium Mining Waste". U.S. EPA, Radiation Protection. August 30, 2012. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ "Uranium Mining and Extraction Processes in the United States Figure 2.1. Mines and Other Locations with Uranium in the Western U.S." (PDF). epa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ^ Laws We Use (Summaries):1978 – Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act(42 USC 2022 et seq.), EPA, retrieved December 16, 2012

- ^ Jerome Price (1982). The Anti-nuclear Movement, Twayne Publishers, p. 65.

- ^ a b Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite. Let’s Take Religious Nuclear Opposition to the Next Level Center for American Progress, April 12, 2010.

- ^ Green Party USA (undated). The Greens/Green Party USA Archived July 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (January 23, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson, Anti-Nuclear Leader, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- ^ Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements p. 45.

- ^ Herman, Robin (September 24, 1979). "Nearly 200,000 Rally to Protest Nuclear Energy". The New York Times. p. B1.

- ^ Williams, Estha. Nuke Fight Nears Decisive Moment Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Valley Advocate, August 28, 2008.

- ^ Colman McCarthy (February 8, 2009). "From Lafayette Square Lookout, He Made His War Protest Permanent". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The Oracles of Pennsylvania Avenue". Al Jazeera Documentary Channel. April 17, 2012. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ Hundreds of Marchers Hit Washington in Finale of Nationwaide Peace March Gainesville Sun, November 16, 1986.

- ^ John Byrne and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Brown & Brutoco 1997, pp. 195–199.

- ^ Lance Murdoch. Pictures: New York MayDay anti-nuke/war march Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine IndyMedia, May 2, 2005.

- ^ Anti-Nuke Protests in New York Archived October 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Fox News, May 2, 2005.

- ^ Wittner, Lawrence S. (June 15, 2009). "Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 7 (25).

- ^ a b Southeast Climate Convergence occupies nuclear facility Indymedia UK, August 8, 2008.

- ^ "Anti-Nuclear Renaissance: A Powerful but Partial and Tentative Victory Over Atomic Energy". commondreams.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ Police arrest 64 at California anti-nuclear protest Reuters, April 6, 2007.

- ^ Anti-nuclear rally held at test site: Martin Sheen among activists cited by police Las Vegas Review-Journal, April 2, 2007.

- ^ For decades, faith has sustained anti-nuclear movement Seattle Times, April 7, 2006.

- ^ Bangor Protest Peaceful; 17 Anti-Nuclear Demonstrators Detained and Released Archived October 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Kitsap Sun, January 19, 2008.

- ^ Twelve Arrests, But No Violence at Bangor Anti-Nuclear Protest Archived October 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Kitsap Sun, June 1, 2008.

- ^ Protest against nuclear reactor Chicago Tribune, October 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Faiola, Anthony (November 24, 2009). "Nuclear power regains support". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Al Gore (2009). Our Choice, Bloomsbury, p. 152.

- ^ Al Gore (2009). Our Choice, p. 157.

- ^ Lovins, Amory (2005). Winning the Oil Endgame Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine p. 259.

- ^ Rocky Mountain Institute (1988). E88-31, Global Warming Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Folbre, Nancy (March 28, 2011). "Renewing Support for Renewables". Economix Blog.

- ^ a b c Romm, Joe (2008). The Self-Limiting Future of Nuclear Power Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine p. 1.

- ^ a b Redekop, Benjamin (April 2010). "'Physicians to a dying planet': Helen Caldicott, Randall Forsberg, and the anti-nuclear weapons movement of the early 1980s". The Leadership Quarterly. 21 (2): 278–291. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.007.

- ^ a b Worldwatch Institute (2008). Building a Low-Carbon Economy Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine in State of the World 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Worldwatch Institute (2008). Building a Low-Carbon Economy Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine in State of the World 2008, p. 80.

- ^ "The Rise of the Anti-nuclear Power Movement" (PDF). utexas.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2005. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ^ Ancient Rockers Try to Recharge Anti-Nuclear Movement Archived November 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Business & Media Institute, November 8, 2007.

- ^ Falk, Jim (1982). Global Fission:The Battle Over Nuclear Power, p. 95.

- ^ "Stewart Brand + Mark Z. Jacobson: Debate: Does the world need nuclear energy?". TED (published June 2010). February 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ Kanellos, Michael. "Newsmaker: From ecowarrior to nuclear champion". CNET News. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Bernard L. "The Nuclear Energy Option". www.phyast.pitt.edu.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Mondragón: The Model For A Vibrant New Economy - EVWORLD.COM". evworld.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Hvistendahl, Mara (December 13, 2007). "Coal Ash Is More Radioactive Than Nuclear Waste". Scientific American.

- ^ Monbiot, George (May 27, 2011). "Nuclear power (Environment), Renewable energy (Environment), Energy (Environment), Environment". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (May 29, 2013). "Paul Allen Lends Support to Pro-Nuclear Doc 'Pandora's Promise'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Michael (June 13, 2013). "'Pandora's Promise' movie review". Washington Post.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (April 27, 2014). "Nuclear Industry Gains Carbon-Focused Allies in Push to Save Reactors". The New York Times.

- ^ "Southern Co. negotiating on nuke loan guarantees". ajc.com.

- ^ Anti-nuclear protesters reach capitol[permanent dead link] Rutland Herald, January 14, 2010.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (February 24, 2010). "Vermont Senate Votes to Close Nuclear Plant". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Rob Pavey. Groups say new Vogtle reactors need study Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Augusta Chronicle, April 21, 2010.

- ^ a b Matthew L. Wald. Critics Challenge Safety of New Reactor Design The New York Times, April 22, 2010.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (October 11, 2010). "Sluggish Economy Curtails Prospects for Building Nuclear Reactors". The New York Times.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (November 5, 2010). "Vermont Nuclear Plant Up for Sale". The New York Times.

- ^ Richard Schiffman (March 12, 2013). "Two years on, America hasn't learned lessons of Fukushima nuclear disaster". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (June 1, 2011). "Report Finds Japan Underestimated Tsunami Danger". The New York Times.

- ^ Kaufman, Leslie (March 19, 2011). "Japan Crisis Could Rekindle U.S. Antinuclear Movement". The New York Times.

- ^ "Vermont Yankee: Countdown to closure". WCAX. March 21, 2011. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Rochelle Becker (April 18, 2011). "Who would pay if nuclear disaster happened here?". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b Martin Finucane (April 6, 2011). "Anti-nuclear sentiment regains its voice at State House rally". Boston.com.

- ^ "Fukushima Fallout: 45 Groups and Individuals Petition NRC to Suspend All Nuclear Reactor Licensing and Conduct a "Credible" Three Mile Island-Style Review". Nuclear Power News Today. April 14, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Renee Schoof (April 12, 2011). "Japan's nuclear crisis comes home as fuel risks get fresh look". McClatchy.

- ^ Carly Nairn (April 14, 2011). "Anti nuclear movement gears up". San Francisco Bay Guardian.

- ^ a b Hsu, Jeremy (February 9, 2012). "First Next-Gen US Reactor Designed to Avoid Fukushima Repeat". Live Science (hosted on Yahoo!). Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Ayesha Rascoe (February 9, 2012). "U.S. approves first new nuclear plant in a generation". Reuters.

- ^ Kristi E. Swartz (February 16, 2012). "Groups sue to stop Vogtle expansion project". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ a b Adam Piore (June 2011). "Nuclear energy: Planning for the Black Swan". Scientific American.

- ^ Jameson Steed (March 12, 2012). "Anti nuclear groups protest San Onofre". Daily Titan.

- ^ Media Relations (August 27, 2013O). "Entergy to Close, Decommission Vermont Yankee". Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Nancy Folbre (March 26, 2012). "The Nurture of Nuclear Power". The New York Times.

- ^ The Pew Research Center For The People and The Press (March 19, 2012). "As Gas Prices Pinch, Support for Oil and Gas Production Grows" (PDF).

- ^ Mark Cooper (June 18, 2013). "Nuclear aging: Not so graceful". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^ a b Matthew Wald (June 14, 2013). "Nuclear Plants, Old and Uncompetitive, Are Closing Earlier Than Expected". The New York Times.

- ^ John Quiggin (November 8, 2013). "Reviving nuclear power debates is a distraction. We need to use less energy". The Guardian.

Bibliography[edit]

- Aron, Joan (1998). Licensed to Kill? The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Shoreham Power Plant, University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Brown, Jerry; Brutoco, Rinaldo (1997). Profiles in Power: The Antinuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-3879-7.

- Byrne, John and Steven M. Hoffman (1996). Governing the Atom: The Politics of Risk, Transaction Publishers.

- Clarfield, Gerald H. and William M. Wiecek (1984). Nuclear America: Military and Civilian Nuclear Power in the United States 1940–1980, Harper & Row.

- Cragin, Susan (2007). Nuclear Nebraska: The Remarkable Story of the Little County That Couldn't Be Bought, AMACOM.

- Dickerson, Carrie B. and Patricia Lemon (1995). Black Fox: Aunt Carrie's War Against the Black Fox Nuclear Power Plant, Council Oak Publishing Company, ISBN 1-57178-009-2

- Fradkin, Philip L. (2004). Fallout: An American Nuclear Tragedy, University of Arizona Press.

- Giugni, Marco (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective, Rowman and Littlefield.

- Jasper, James M. (1997). The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39481-6

- Lovins, Amory B. and Price, John H. (1975). Non-Nuclear Futures: The Case for an Ethical Energy Strategy, Ballinger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 0-88410-602-0

- McCafferty, David P. (1991). The Politics of Nuclear Power: A History of the Shoreham Power Plant, Kluwer.

- Miller, Byron A. (2000). Geography and Social Movements: Comparing Anti-nuclear Activism in the Boston Area, University of Minnesota Press.

- Natti, Susanna and Acker, Bonnie (1979). No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power, South End Press.

- Ondaatje, Elizabeth H. (c1988). Trends in Antinuclear Protests in the United States, 1984–1987, Rand Corporation.

- Peterson, Christian (2003). Ronald Reagan and Antinuclear Movements in the United States and Western Europe, 1981–1987, Edwin Mellen Press.

- Polletta, Francesca (2002). Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-67449-5

- Pope, Daniel (2008). Nuclear Implosions: The Rise and Fall of the Washington Public Power Supply System, Cambridge University Press.

- Price, Jerome (1982). The Antinuclear Movement, Twayne Publishers.

- Smith, Jennifer (Editor), (2002). The Antinuclear Movement, Cengage Gale.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K. (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific.

- Surbrug, Robert (2009). Beyond Vietnam: The Politics of Protest in Massachusetts, 1974–1990, University of Massachusetts Press.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective, University of California Press.

- Wellock, Thomas R. (1998). Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978, The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-15850-0

- Wills, John (2006). Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon, University of Nevada Press.

- Rüdig, Wolfgang (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy. Longman Current Affairs. ISBN 978-0-582-90269-5.

External links[edit]

- Cancelled Nuclear Units Ordered in the United States

- Nuclear Reactor Shutdown List

- Public support for new nuclear power plants low, according to UN-backed poll

- Anti-nuclear renaissance: a powerful but partial and tentative victory over atomic energy

- Nuclear Power's Global Expansion: Weighing Its Costs and Risks Archived January 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Beyond Nuclear 2013 response Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine to the views of Hansen, Caldeira, Emanuel, and Wigley, about nuclear power.