Zulu Dawn

| Zulu Dawn | |

|---|---|

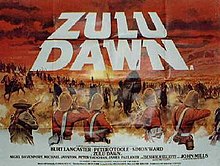

Film poster by Tom Chantrell | |

| Directed by | Douglas Hickox |

| Written by | Cy Endfield Anthony Storey |

| Produced by | Nate Kohn James Sebastian Faulkner |

| Starring | Burt Lancaster Peter O'Toole Simon Ward Nigel Davenport Michael Jayston Peter Vaughan Denholm Elliott James Faulkner John Mills |

| Cinematography | Ousama Rawi |

| Edited by | Malcolm Cooke |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | American Cinema Releasing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11.75 million[1]($48.3 million in 2023 dollars)[2] |

Zulu Dawn is a 1979 American adventure war film about the historical Battle of Isandlwana between British and Zulu forces in 1879 in South Africa. The screenplay was by Cy Endfield, from his book, and Anthony Storey. The film was directed by Douglas Hickox. The score was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

Zulu Dawn is a prequel to Zulu, released in 1964, which depicts the historical Battle of Rorke's Drift later the same day, and which was co-written and directed by Cy Endfield.

Plot[edit]

In the Cape Colony in January 1879, British Army officer Lord Chelmsford plots with diplomat Sir Henry Bartle Frere to annex the neighbouring Zulu Empire, which they perceive as a threat to the Cape Colony's emerging industrial economy. Frere issues an ultimatum to the Zulu king, Cetshwayo, demanding that he dissolve the Zulu military; an indignant Cetshwayo rebuffs the demand, providing Lord Chelmsford and Frere with a casus belli against the Zulus. Despite objections from prominent individuals in the Cape Colony and Great Britain, Frere authorises Lord Chelmsford to command a British expeditionary force to invade the Zulu Empire.

The British expeditionary force marches into the Zulu Empire, with Lord Chelmsford directing it towards the Zulu capital, Ulundi. Eager to bring the war to a swift conclusion, the British become increasingly frustrated as the Zulu military adopted a Fabian strategy, refusing to engage in a pitched battle; a few skirmishes occurred between British and Zulu scouts with indecisive results. Three Zulu warriors allowed themselves to be captured in a skirmish and are interrogated by the British, but refused to divulge any information and eventually escape, informing their commander of the British dispositions. Halfway to Ulundi, Lord Chelmsford, ordered the British force to make camp at the base of Mount Isandlwana, ignoring the advice of his Boer attendants to fortify the camp and transform his supply wagons into a laager.

Upon receiving inaccurate reports from his scouts concerning the Zulus' dispositions, Lord Chelmsford leads half the British force on a wild goose chase far from the camp against a phantom Zulu force. The next day, the British camp receives reinforcements led by Colonel Durnford, who dispatches scouts to reconnoiter the surrounding area before leaving the camp to personally scout the region. One of the British scouting parties discovers a Zulu force massing at the bottom of a nearby valley. The Zulu force quickly attacks the British camp, but are initially repulsed; however, they spread out and adopt a strategy of encircling the British, who are eventually pushed back after they run out of ammunition. A massed infantry charge by the Zulu force breaks the British lines, causing them to retreat back towards their camp. Overwhelmed by the attacking Zulus, the British force collapses and is quickly massacred.

Zulu warriors quickly hunt down any British survivors fleeing the battle, while several British soldiers attempt an unsuccessful last stand. The British camp's commander, Colonel Pulleine, entrusts a regimental colour to his soldiers who attempt to carry it safely back to the Cape Colony; they pass numerous dead and dying British soldiers during their journey. Eventually reaching the Buffalo River, the British soldiers are discovered and killed by Zulu warriors; the colour is captured by a Zulu. Lieutenant Vereker, who lies wounded and trapped under his fallen horse, shoots and kills the Zulu wielding the colour, who drops it into the river, where it floats out of reach of the Zulu force. In the evening, Lord Chelmsford returns to the scene of the battle, and receives news that a Zulu force has attacked Rorke's Drift. Zulu warriors drag captured artillery back to Ulundi.

Cast[edit]

- Peter O'Toole as Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford

- Burt Lancaster as Colonel Anthony Durnford

- Denholm Elliott as Colonel Henry Pulleine

- James Faulkner as Lieutenant Teignmouth Melvill

- Christopher Cazenove as Lieutenant Coghill

- Simon Ward as Lieutenant William Vereker

- Bob Hoskins as Colour Sergeant Williams

- Nigel Davenport as Colonel Hamilton-Brown

- Peter Vaughan as Quartermaster Bloomfield

- Michael Jayston as Colonel Henry Hope Crealock

- Ronald Pickup as Lieutenant Harford

- Ronald Lacey as Norris "Noggs" Newman

- John Mills as Sir Henry Bartle Frere

- Simon Sabela as King Cetshwayo

- Ken Gampu as Mantshonga

- Abe Temba as Uhama

- Gilbert Tiabane as Bayele

- Dai Bradley as Private Williams

- Paul Copley as Corporal Storey

- Donald Pickering as Major Russell R.A.

- Nicholas Clay as Lieutenant Raw

- Phil Daniels as Boy Pullen

- Ian Yule as Corporal Fields

- Peter J. Elliott as Sentry

- Brian O'Shaughnessy as Major Smith R.A.

- Freddie Jones as Bishop John Colenso

Production[edit]

The script was originally written by Cy Endfield.[3]

The Lamitas Property Investment Corporation raised money for the film. They financed a series of films, including several in South Africa, such as The Wild Geese (1978). The company committed about £5 million to Zulu Dawn, most of it raised from a Swiss bank, the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas.[4] HBO helped guarantee finance.[5] The budget was initially set at $6.5 million but the budget kept increasing and eventually cost $11.75 million, despite coming in only two days over schedule.[1]

Jake Eberts was involved in raising finance for the film. He had to guarantee Burt Lancaster's salary when Lancaster's agent insisted on one. This meant Eberts was liable for the loan. In 1983 the interest made this £450,000. Eberts spent years paying it back.[6]

John Hurt was cast in a lead role but was refused entry to South Africa. This confused Hurt who was not particularly political. It was thought South African Intelligence may have confused him with the actor John Heard, who had been arrested in an anti-Apartheid march.[7]

Orion Pictures picked the film up for worldwide distribution through Warner Bros. and other companies.[1]

Shooting[edit]

Every day over 1,000 people were involved in filming,[8] with Zulu extras being paid £2.70 per day.[9]

In 1978, the producers and financiers agreed to defer their fees and no completion guarantee was in place to get the film finished.[1] Norma Foster was a liaison between the South African government (notably the Minister of Information, Dr Connie Mulder) and the filmmakers; she later claimed the producers owed her £20,000. Co-producers, James Faulkner and Barrie Saint Clair, claimed they were owed £100,000 in deferred fees. Over 100 creditors in South Africa claimed they were owed £250,000. Faulkner and Saint Clair sought an injunction to block screening of the film until they were paid.[1] Lamitas denied liability for the money, claiming expenses exceeded the agreed budget and the injunction was lifted May 21, 1979.[1] They later offered to settle for 25 pence on the pound.[4]

In 1978, David Japp, founder and MD of London-based composers agency The First Composers Company, met the film's producer Nate Kohn and suggested he use composer Mike Batt to write the score for the film. Although possibly best known for his pop compositions for children's' TV series "The Wombles" and the pop-chart hits of the songs from the series, and in particular for the song "Bright Eyes" from the animated film "Watership Down", Batt was an accomplished composer and arranger of orchestral music.

Batt was commissioned to write the score, but shortly after the commissioning agreement was signed and the first 1/3rd of the fee paid, Kohn informed Japp that the producers had changed their minds and wanted a "name" to help with the films promotion. Batt was devastated and refused to accept the rest of the "pay or play" fee, due under the terms of the signed commissioning agreement

Japp sent his US client list to Kohn, who selected Elmer Bernstein, composer of such films as the Magnificent Seven, The Ten Commandments, The Great Escape, To Kill a Mockingbird and Thoroughly Modern Millie, for which Bernstein had won an Oscar. Japp managed to negotiate the highest fee that Bernstein had ever been paid and it was only after the score had been recorded at Abbey Road studios and the film shown the Cannes Film Festival that Japp found out the producers mistakenly thought they were hiring Leonard Bernstein, famed conductor and composer of dozens of orchestral compositions and films, possibly the best known of which is West Side Story - which was the reason the producers wanted "Bernstein" as composer.

Reception[edit]

The film has received mixed reviews. On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, Zulu Dawn has an approval rating of 50% based on 8 reviews and an average rating of 6.03/10.[10]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Free 'Zulu Dawn' From Restraint". Variety. 23 May 1979. p. 3.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Dineen, Michael (18 June 1978). "Cy's is right to type fast: Small businesses bureau". The Observer. p. 16.

- ^ a b Beresford, D. (10 August 1979). "Zulu victory starts a second battle". The Guardian.

- ^ "BUSY BUYING FOR TELEVISION". The Irish Times. 25 May 1979. p. 10.

- ^ Eberts, Jake; Illott, Terry (1990). My indecision is final. Faber and Faber. p. 156-157. ISBN 9780571148882.

- ^ Hall, Ruth (28 July 1978). "London Diary". New Statesman. Vol. 96, no. 2471. p. 119.

- ^ Lukk, Tiiu (February 1979). "Filming "Zulu Dawn" on Location in South Africa". American Cinematographer. Vol. 60, no. 2.

- ^ "A High Shine for Olivier's Star". Los Angeles Times. 20 July 1978. p. i15.

- ^ "Zulu Dawn". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

External links[edit]

- Zulu Dawn at IMDb

- Zulu Dawn at Rotten Tomatoes

- Zulu Dawn at AllMovie

- http://www.takeoneinplease.com for commentary in British film section on how Victorians managed to change perceptions of battles of Rorke's Drift and Isandhlwana.

- 1979 films

- Prequel films

- 1970s war films

- 1970s historical films

- American historical films

- 1970s English-language films

- War films based on actual events

- Films directed by Douglas Hickox

- Films scored by Elmer Bernstein

- Films set in South Africa

- Films set in the British Empire

- Films shot in South Africa

- Films set in 1879

- Works about the Anglo-Zulu War

- 1970s American films

- American prequel films

- British Empire war films