Zardoz

| Zardoz | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Ron Lesser | |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Written by | John Boorman |

| Produced by | John Boorman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | John Merritt |

| Music by | David Munrow |

Production company | John Boorman Productions Ltd. (uncredited) |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox (United States) Fox-Rank Distributors Ltd. (United Kingdom) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$1.57 million[3] |

| Box office | US$1.8 million (U.S. and Canada rentals)[4] |

Zardoz is a 1974 science fantasy film written, produced, and directed by John Boorman and starring Sean Connery and Charlotte Rampling. It depicts a post-apocalyptic world where barbarians (the Brutals) worship the stone idol Zardoz while growing food for a hidden elite, the Eternals. The Brutal Zed becomes curious about Zardoz, and his curiosity forces a confrontation between the two camps.

Boorman decided to make the film after his abortive attempt at dramatising The Lord of the Rings. Burt Reynolds was originally given the role, but subsequently declined the role due to illness. Sean Connery, in an attempt to reinvent himself after portraying James Bond, signed on.[5] It was shot entirely in County Wicklow, in the east of Ireland, and used locations at the Glencree Centre for Reconciliation, Hollybrook Hall (now Brennanstown Riding School) in Kilmacanogue, and Luggala mountain for the dramatic wasteland sequences.[6]

Plot[edit]

In the year 2293, the human population is divided into the immortal "Eternals" and mortal "Brutals". The Brutals live in an irradiated wasteland, growing food for the Eternals, who live apart in "the Vortex," leading a luxurious but aimless existence on the grounds of a country estate. The Brutal Exterminators kill and terrorize other "Brutals" at the orders of Zardoz, a flying stone head which supplies them with weapons in exchange for the food they collect. Zed, a Brutal Exterminator, hides aboard Zardoz during one trip, temporarily "killing" its Eternal operator-creator Arthur Frayn.

Arriving in the Vortex, Zed meets two Eternals – Consuella and her assistant May. Overcoming Zed with psychic powers, they make him a prisoner and menial worker within their community. Consuella wants Zed destroyed so that the resistance cannot use him to start a revolution; others, led by May and the subversive Eternal Friend, insist on keeping him alive for further study, while secretly planning to overthrow the government and end humanity's suffering.

In time, Zed learns the nature of the Vortex. The Eternals are overseen and protected from death by the Tabernacle, an artificial intelligence. Given their limitless lifespan, the Eternals have grown bored and corrupt, and are descending into madness. The needlessness of procreation has rendered the men impotent and meditation has replaced sleep. Others fall into catatonia, forming the social stratum the Eternals have named the "Apathetics". The Eternals spend their days stewarding humankind's vast knowledge, baking special bread from the grain deliveries and participating in communal meditation rituals. To give life more meaning and in a failed attempt to stop humanity from becoming permanently catatonic, the Vortex developed complex social rules whose violators are punished with artificial aging. The most extreme offenders are condemned to permanent old age. Eternals who have managed to die, usually by accident, are then reborn into another healthy, synthetically reproduced body that is identical to the one they lost.

Zed is less brutal and far more intelligent than the Eternals think he is. Genetic analysis reveals he is the ultimate result of long-running eugenics experiments devised by Arthur Frayn, who controlled the outlands with the Exterminators. Zardoz's aim was to breed a superman who would penetrate the Vortex and save human-kind from its hopelessly stagnant status quo. In the ruins of the old world, Arthur Frayn encouraged Zed to learn to read and led him to the book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Understanding the origin of the name Zardoz – Wizard of Oz – brought Zed to a true awareness of Frayn as a manipulator. Infuriated with this realization, Zed decided to further investigate the mystery of Zardoz.

As Zed divines the nature of the Vortex and its problems, the Eternals use him to fight their internecine quarrels. Led by Consuella, the Eternals decide to kill Zed and to age Friend. Zed escapes and, aided by May and Friend, absorbs all the Eternals' knowledge, including that of the Vortex's origin, to destroy the Tabernacle. While absorbing their knowledge Zed impregnates May and a few of her followers as he is transformed from a revenge-seeking Exterminator. Zed shuts down the Tabernacle, thus disabling the force-fields and perception filters surrounding the Vortex. This helps the Exterminators invade the Vortex and kill most of the Eternals—who welcome death as a release from their boring existence. May and several of her followers escape the massacre, heading out to bear their offspring as enlightened but mortal beings among the Brutals.

Consuella, having fallen in love with Zed, gives birth within the remains of the stone head. The baby boy matures as his parents age. When the youth leaves his parents, they keep growing old and eventually die. Nothing remains in the space but painted handprints on the wall and Zed's revolver.

Cast[edit]

- Sean Connery as Zed

- Charlotte Rampling as Consuella

- Sara Kestelman as May

- Niall Buggy as Arthur Frayn / Zardoz

- John Alderton as Friend

- Sally Anne Newton as Avalow

- Bosco Hogan as George Saden

- Jessica Swift as Apathetic

- Reginald Jarman as voice of Death

- Bairbre Dowling as Star

- Christopher Casson as Old Scientist

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Boorman was inspired to write Zardoz while preparing to adapt J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings for United Artists, but when the studio became hesitant about the cost of producing film versions of Tolkien's books, Boorman continued to be interested in the idea of inventing a strange new world.[8] He wrote Zardoz with William (Bill) Stair, a long time collaborator. Boorman said that he "wanted to make a film about the problems of us hurtling at such a rate into the future that our emotions are lagging behind."[9] The original draft was set five years in the future and was about a university lecturer who became obsessed with a young girl whose disappearance prompted him to seek her out in the communes where she had lived. Boorman visited some communes for research, but decided to set the story far in the future, when society had collapsed.[9]

In the audio commentary Boorman says he developed the emergent society, focusing on a central character "who penetrated it. He'd be mysteriously chosen and at the same time manipulated — and I wanted the story to be told in the form of a mystery, with clues and riddles which unfold, the truth slowly peeled away."[9] The script was influenced by the writings of Frank L. Baum, T.S. Eliot and Tolkien but, above all, on the Philosophy, ‚Quasi’ Religion called Gnosis(The Tabernacle proclaims Himself as ‚The Sum of all Knowledge (and in this, echoing the ‚Demiurge’, a lesser God, that seeks to hinder and harm Human Development)),and drew inspiration from medieval Arthurian quests, viewed under its later encarnations(Wolfram von Eschenbach and Thomas Mallory, from where Boorman Tool Material for his 1981 Movie, ‚Excalibur‘).[10] "It's about inner rather than outer space," said Boorman. "It's closer to the better science fiction literature which is more metaphysical. Most of the science fiction that gives the genre a bad name is adventure stories in space clothes."[10]

"Nobody wanted to do it. Warners didn’t want to do it, even though I'd made a shitload of money for them," Boorman said. His then-agent David Begelman knew the head of 20th Century Fox wanted to make a film with the director, and offered the executive the script to read, but insisted on a decision within two hours. "It's either yes or no," Begelman told him. "You have no approvals, and it’s a million dollars negative pick-up". Boorman said that "[the] Fox guy came to London, and I was very nervous, so we went for lunch whilst he read the script. When he finally came out of the office his hand was shaking, clearly with no idea of what to make of it. Begelman went straight up to him and said, 'Congratulations!' He never gave the poor guy a chance."[11]

Casting[edit]

In April 1973, Boorman announced the film would star Burt Reynolds and Charlotte Rampling.[12] Reynolds had previously starred in Boorman's film Deliverance (1972). However, Reynolds had to pull out due to illness and was replaced by Sean Connery.[13] Boorman stated, "Connery had just stopped doing the Bond films and he wasn’t getting any jobs, so he came along and did it."[11] Connery's casting was announced in May 1973 the week before filming was to begin.[14] Rampling said she did the film because it is "poetry. It clearly states: love your body, love nature, and love what you come from".[15] Boorman had a cameo, as did his three daughters, Daisy, Katrine, and Telsche.

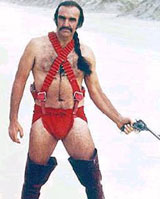

Locals were hired to help with the production. A group of County Wicklow artisans were hired to create many of the film's futuristic costumes. The costumes were designed by Boorman's first wife, Christel Kruse (the credits say they were made by La Tabard Boutique in Dublin), and were creations based on "pure intuition". She decided that, because the Eternals' lives were purely metaphysical and colorless, this should be incorporated in their costumes too. As The Brutals were lower, more primitive beings, Christel decided that they would not care much about what they were wearing, only what was functional and comfortable.[16] As stated in the magazine Dark Worlds Quarterly "functional" and "comfortable" costumes ended up meaning that the costumes were extremely revealing, "It is the costumes for the Brutal Exterminators, and Zed in particular, that raise the eyebrows. [In] thigh-high leather boots, crossed bandoliers and ... shorts that can be described as 'skimpy', the Brutals, and Connery in particular, exude raw masculinity, particularly as they ride their steeds and fire their guns."[17]

Filming[edit]

The film was financed by 20th Century Fox and produced by Boorman's own self-titled company, John Boorman Productions Ltd., which was based in Dublin,[18][19] principal photography for Zardoz took place from May to August 1973.[20] It was reported that Stanley Kubrick was an uncredited technical advisor on the film.[1]

The production was shot entirely on location in Republic of Ireland and was based out of Ardmore Studios in Bray, County Wicklow where the interior shots were completed. Connery lived in Bray while shooting; his house went on the market in 2020, some months before his death.[21] Boorman used the location for several films, including Excalibur (1981).[22][23][24]

In the audio commentary, Boorman related how political and cultural conditions in Ireland at the time affected the production, saying that it was "very difficult to get women to bare their breasts" as nudity was a prominent feature in several sequences. He added that a ban on importing rifles, which had been imposed because of the Irish Republican Army, nearly prevented the movie from being made.[24]

Soundtrack[edit]

Boorman commissioned David Munrow, director of the Early Music Consort, to compose the score. While the film is set in the distant future (the 23rd century approximately), Boorman believed futuristic music would contain a variety of old-world instruments. Boorman instructed Munrow to use a variety of medieval instruments including notch flutes, medieval bells and gemshorns. These instruments, plus snatches of Beethoven's Seventh, gave the movie a truly unusual soundtrack.

Along with David Munrow's medieval ensemble, the Zardoz soundtrack features Beethoven's "Symphony No.7" in A, 2nd movement, played by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Conducted by Eugen Jochum.[25]

Release[edit]

Zardoz was released in theaters on February 6, 1974, in Los Angeles and New York. When the film was released, it was immediately met with terrible reviews. Along with the scathing reviews, the public reacted very poorly to the confusing world of Zardoz. According to a Starlog Magazine article on the film, "these reviewers (and the general public) failed to understand many of Boorman's analogies and philosophical statements".[16] Moviegoers reported that "when dissatisfied patrons from the previous showing exited the lobby, they would encourage those waiting to leave. Many times they did".[16] Zardoz barely made back its budget, and ultimately earned $1.8 million in box office rentals in the United States and Canada.[4]

Home media[edit]

Zardoz was first released on VHS in 1984.[26] The film was released on Blu-Ray on April 14, 2015.[27]

Reception[edit]

Nora Sayre of The New York Times wrote Zardoz "is science fiction that rarely succeeds in fulfilling its ambitious promises... Despite its pseudo-scientific gimcracks and a plethora of didactic dialogue, Zardoz is more confusing than exciting even with a frenetic, shoot-em-up climax".[28] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave it two-and-a-half stars out of four and called it a "genuinely quirky movie, a trip into a future that seems ruled by perpetually stoned set decorators... The movie is an exercise in self-indulgence (if often an interesting one) by Boorman, who more or less had carte blanche to do a personal project after his immensely successful Deliverance".[29] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave it one star out of four and called it "a message movie all right, and the message is that social commentary in the cinema is best restrained inside of a carefully-crafted story, not trumpeted with character labels, special effects, and a dose of despair that celebrates the director's humanity while chastising the profligacy of the audience".[30] Variety reported the "direction, good; script, a brilliant premise which unfortunately washes out in climactic sound and fury; and production, outstanding, particularly special visual effects which are among the best in recent years and belie the film's modest cost".[31]

Jay Cocks of Time magazine called the film "visually bounteous", with "bright intervals of self-deprecatory humor that lighten the occasional pomposity of the material".[32] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times was generally positive and wrote that its $1.5 million budget was "an unbelievably low price for the dazzle on the screen and a tribute to creative ingenuity and personal dedication. It is a film which buffs and would-be filmmakers are likely to be examining with interest for years to come".[33] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote that the script "lacks the human dimensions that would make us care about the big visual sequences" and burdened the actors with "unspeakable dialogue", and also remarked that Connery "acts like a man who agreed to do something before he grasped what it was".[34]

Re-appraisal[edit]

It has been noted that Zardoz has developed a cult following.[16][35][36] In 1992, Geoff Boucher, writing in the Los Angeles Times, felt that Boorman achieved his vision to a degree, and that "for fans of wild science fiction, the film is a trippy examination of what happens when intellect overpowers humanity and humans taste immortality".[37] Jonathan Rosenbaum, reviewing in the Chicago Reader, called it "John Boorman's most underrated film – an impossibly ambitious and pretentious but also highly inventive, provocative, and visually striking SF adventure with metaphysical trimmings".[38]

In 2007, Will Thomas of Empire Magazine wrote of Zardoz: "You have to hand it to John Boorman. When he's brilliant, he's brilliant (Point Blank, Deliverance) but when he's terrible, he's really terrible. A fascinating reminder of what cinematic science fiction used to be like before Star Wars, this risible hodge-podge of literary allusions, highbrow porn, sci-fi staples, half-baked intellectualism and a real desire to do something revelatory misses the mark by a hundred miles but has elements – its badness being one of them – that make it strangely compelling".[5] Channel 4 called it "Boorman's finest film" and a "wonderfully eccentric and visually exciting sci-fi quest" that "deserves reappraisal".[7] In his audio commentary to the DVD/Blu-ray (first released in 2000, and included in subsequent releases), Boorman claimed it "was a very indulgent and personal film" but one he admits he may not have had the budget to properly achieve.[24] It has since been the subject of re-appraisal and become a cult classic, described by Reader's Digest as "one of the wildest, most ambitious films of the 1970s."[39]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported an approval rating of 49%, with an average score of 5.6/10, based on 39 reviews. Its consensus reads, "Zardoz is ambitious and epic in scope, but its philosophical musings are rendered ineffective by its supreme weirdness and rickety execution".[40] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 46 out of 100 based on nine critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[41]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Zardoz at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ "Zardoz". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 257.

- ^ a b Solomon 1989, p. 232.

- ^ a b Thomas, Will (2 February 2007). "Zardoz". Empire Magazine.

- ^ "Filming Locations for John Boorman's Zardoz (1973), in the Republic of Ireland". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations.

- ^ a b Review of Zardoz from Channel 4

- ^ Champlin, Charles (11 January 1974). "Visions of the Future". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Strick, Philip (Spring 1974). "Zardoz and John Boorman". Sight & Sound. 43 (2): 73 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Blume, Mary (7 April 1974). "Boorman at 40: Losing a Millstone at a Milestone". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 24 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Thrift, Matt. "John Boorman on Kubrick, Connery and the lost Lord of The Rings script". Little White Lies.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (22 April 1973). "'Hair' Turns Silver (Screen)". The New York Times. p. 107.

- ^ Haber, Joyce (21 May 1973). "Laying to Rest Burt-Is-Dying Rumor". Los Angeles Times. Part VI, p. 10.

- ^ Murphy, Mary (18 May 1973). "Movie Call Sheet: Kubrick Sets 'Barry Lyndon'". Los Angeles Times. Part VII, p. 16.

- ^ Kramer, Carol (17 March 1974). "Movies: Self-searching, on a rambling Rampling route". Chicago Tribune. Section 4, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Maronie, Sam J. (March 1982). "Return to the Vortex". Starlog. No. 56. pp. 19, 48–49 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jackson, M. D. (17 April 2020). "The 'Barely-There' Costumes (and Plot) of Zardoz". Dark Worlds Quarterly. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Trade and Industry, Volume 15, April to June 1974. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1974. p. 62. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "John Boorman Productions Limited". DueDil. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "John Boorman's Zardoz". Sight & Sound. 42 (4): 210. Autumn 1973 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "It's 007 on the double with two former homes of James Bond star Sean Connery being offered for sale in Ireland and France". independent. 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Filming Locations for John Boorman's Zardoz (1973), in the Republic of Ireland". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations.

- ^ "Sean Connery-Did you know?". WicklowNews. 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "35 Things We Learned From John Boorman's Zardoz Commentary". Film School Rejects. 18 May 2015.

- ^ Zardoz (1974) - IMDb, retrieved 28 April 2020

- ^ "Zardoz | VHSCollector.com". VHS Collector. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Zardoz Blu-ray Release Date April 14, 2015, retrieved 28 April 2020

- ^ Sayre, Nora (7 February 1974). "The Screen: Wayne, Off the Range". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Zardoz (review)". Chicago Sun Times.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (19 March 1974). "Gloom and doom infect 'Zardoz'". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 4.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Zardoz". Variety. 13 January 1974. p. 13.

- ^ Cocks, Jay (18 February 1974). "Cinema: Celtic Twilight". Time.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (3 February 1974). "'Zardoz': It's Not Nice to Fool Mother Nature". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, pp. 1, 24, 45.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (18 February 1974). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Shankel, Jason; Stamm, Emily; Krell, Jason (7 March 2014). "30 Cult Movies That Absolutely Everybody Must See". Gizmodo. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Telotte, J. P.; Duchovnay, Gerald (2015). Science Fiction Double Feature: The Science Fiction Film as Cult Text. Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-78138183-0.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (22 October 1992). "Visual Technology Goes Wild in 'Zardoz'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (26 October 1985). "Zardoz". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Retro review: Zardoz—the wildest film of the 70s - Reader's Digest". www.readersdigest.co.uk.

- ^ "Zardoz (1974)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ "Zardoz Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

Bibliography[edit]

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

External links[edit]

- Zardoz at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Zardoz at TCMDB

- Zardoz at Letterbox DVD

- Zardoz at IMDb

- Zardoz at Box Office Mojo

- 1974 films

- 1970s dystopian films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s fantasy films

- 1970s science fiction films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Irish fantasy films

- Irish science fiction films

- American science fantasy films

- American dystopian films

- Films directed by John Boorman

- Films set in the 23rd century

- Films shot in County Wicklow

- Internet memes

- Film and television memes

- American post-apocalyptic films

- Religion in science fiction

- 1970s American films

- British dystopian films