Yakuza

The word yakuza in katakana (ヤクザ) | |

| Founded | 17th century (presumed to have originated from the Kabukimono) |

|---|---|

| Territory | Primarily Japan, particularly, Kantō/Tokyo, Kansai, Kyushu/Fukuoka, and Chūbu; also internationally in, South Korea, Australia,[1] and the Western United States (Hawaii and California) |

| Ethnicity | Primarily Japanese; occasionally Koreans and Japanese Americans |

| Membership | 10,400 members[2] 10,000 quasi-members[2] |

| Activities | Varied, including illegitimate businesses, an array of criminal and non-criminal activities. |

| Notable members | Principal clans: |

Yakuza (Japanese: ヤクザ, IPA: [jaꜜkɯza]; English: /jəˈkuːzə, ˈjækuːzə/), also known as gokudō (極道, "the extreme path", IPA: [gokɯꜜdoː]), are members of transnational organized crime syndicates originating in Japan. The Japanese police and media, by request of the police, call them bōryokudan (暴力団, "violent groups", IPA: [boːɾʲokɯꜜdaɴ]), while the yakuza call themselves ninkyō dantai (任侠団体, "chivalrous organizations", IPA: [ɲiŋkʲoː dantai]). The English equivalent for the term yakuza is gangster, meaning an individual involved in a Mafia-like criminal organization.[3]

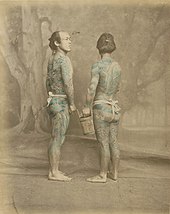

The yakuza are known for their strict codes of conduct, their organized fiefdom nature, and several unconventional ritual practices such as yubitsume, or amputation of the left little finger.[4] Members are often portrayed as males with heavily tattooed bodies and wearing fundoshi, sometimes with a kimono or, in more recent years, a Western-style "sharp" suit covering them.[5] This group is still regarded as being among "the most sophisticated and wealthiest criminal organizations".[6]

At their height, the yakuza maintained a large presence in the Japanese media, and they also operated internationally. In 1963, the number of yakuza members and quasi-members reached a peak of 184,100.[7] However, this number has drastically dropped, a decline attributed to changing market opportunities and several legal and social developments in Japan that discourage the growth of yakuza membership.[8] In 1991 it had 63,800 members and 27,200 quasi-members, but by 2023 it had only 10,400 members and 10,000 quasi-members.[2] The yakuza are aging because young people do not readily join, and their average age at the end of 2022 was 54.2 years: 5.4% in their 20s, 12.9% in their 30s, 26.3% in their 40s, 30.8% in their 50s, 12.5% in their 60s, and 11.6% in their 70s or older, with more than half of the members in their 50s or older.[9]

The yakuza still regularly engage in an array of criminal activities, and many Japanese citizens remain fearful of the threat these individuals pose to their safety.[10] There remains no strict prohibition on yakuza membership in Japan today, although many pieces of legislation have been passed by the Japanese Government aimed at impeding revenue and increasing liability for criminal activities.[10]

Etymology[edit]

The name yakuza originates from the traditional Japanese card game Oicho-Kabu, a game in which the goal is to draw three cards adding up to a score of 9. If the sum of the cards exceeds 10, its second digit is used as the score instead, and if the sum is exactly 10, the score is 0. If the three cards drawn are 8-9-3 (pronounced ya-ku-sa in Japanese), the sum is 20 and therefore the score is zero, making it a tie for the worst possible hand that can be drawn.[11][12] In Japanese, the word yakuza is commonly written in katakana (ヤクザ).

Origins[edit]

Despite uncertainty about the single origin of yakuza organizations, most modern yakuza derive from two social classifications which emerged in the mid-Edo period (1603–1868): tekiya, those who primarily peddled illicit, stolen or shoddy goods; and bakuto, those who were involved in or participated in gambling.[13]

Tekiya (peddlers) ranked as one of the lowest social groups during the Edo period. As they began to form organizations of their own, they took over some administrative duties relating to commerce, such as stall allocation and protection of their commercial activities.[14] During Shinto festivals, these peddlers opened stalls and some members were hired to act as security. Each peddler paid rent in exchange for a stall assignment and protection during the fair.

The tekiya were a highly structured and hierarchical group with the oyabun (boss) at the top and kobun (gang members) at the bottom.[15] This hierarchy resembles a structure similar to the family – in traditional Japanese culture, the oyabun was often regarded as a surrogate father, and the kobun as surrogate children.[15] During the Edo period, the government formally recognized the tekiya. At this time, within the tekiya, the oyabun were appointed as supervisors and granted near-samurai status, meaning they were allowed the dignity of a surname and two swords.[16]

Bakuto (gamblers) had a much lower social standing even than traders, as gambling was illegal. Many small gambling houses cropped up in abandoned temples or shrines at the edges of towns and villages all over Japan. Most of these gambling houses ran loan-sharking businesses for clients, and they usually maintained their own security personnel. Society at large regarded the gambling houses themselves, as well as the bakuto, with disdain. Much of the undesirable image of the yakuza originates from bakuto; this includes the name yakuza itself.

Because of the economic situation during the mid-Edo period and the predominance of the merchant class, developing yakuza groups were composed of misfits and delinquents who had joined or formed the groups to extort customers in local markets by selling fake or shoddy goods.[clarification needed]

Shimizu Jirocho (1820–1893) is Japan's most famous yakuza and folk hero.[17] He was born Chogoro Yamamoto, but changed his name when he was adopted, a common Japanese practice.[18] His life and exploits were featured in sixteen films between 1911 and 1940.

The roots of the yakuza survive today in initiation ceremonies, which incorporate tekiya or bakuto rituals. Although the modern Yakuza has diversified, some gangs still identify with one group or the other; for example, a gang whose primary source of income is illegal gambling may refer to themselves as bakuto.

Kyushu[edit]

Kyushu island (and particularly its northern prefecture Fukuoka) has a reputation for being a large source of yakuza members,[19] including many renowned bosses in the Yamaguchi-gumi.[20] Isokichi Yoshida (1867–1936) from the Kitakyushu area was considered by some scholars and political watchers as one of the first renowned modern yakuza.[21] Recently Shinobu Tsukasa and Kunio Inoue, the bosses of the two most powerful clans in the Yamaguchi-gumi, originate from Kyushu. Fukuoka, the northernmost part of the island, has the largest number of designated syndicates among all of the prefectures.[22]

Organization and activities[edit]

Structure[edit]

During the formation of the yakuza, they adopted the traditional Japanese hierarchical structure of oyabun-kobun where kobun (子分; lit. foster child) owe their allegiance to the oyabun (親分, lit. foster parent). In a much later period, the code of jingi (仁義, justice and duty) was developed where loyalty and respect are a way of life.

The oyabun-kobun relationship is formalized by ceremonial sharing of sake from a single cup. This ritual is not exclusive to the yakuza – it is also commonly performed in traditional Japanese Shinto weddings, and may have been a part of sworn brotherhood relationships.[23]

During the World War II period in Japan, the more traditional tekiya/bakuto form of organization declined as the entire population was mobilised to participate in the war effort and society came under the control of the strict military government. However, after the war, the Yakuza adapted again.

Prospective yakuza come from all walks of life. The most romantic tales tell how yakuza accept sons who have been abandoned or exiled by their parents. Many yakuza start out in junior high school or high school as common street thugs or members of bōsōzoku gangs. Perhaps because of its lower socio-economic status, numerous yakuza members come from Burakumin and ethnic Korean backgrounds. Low-ranking youth may be referred to as chinpira or chimpira.[24][25]

Yakuza groups are headed by an oyabun or kumichō (組長, family head) who gives orders to his subordinates, the kobun. In this respect, the organization is a variation of the traditional Japanese senpai-kōhai (senior-junior) model. Members of yakuza gangs cut their family ties and transfer their loyalty to the gang boss. They refer to each other as family members—fathers and elder and younger brothers. The yakuza is populated almost entirely by men and the very few women who are acknowledged are the wives of bosses, who are referred to by the title ane-san (姐さん, older sister). When the 3rd Yamaguchi-gumi boss (Kazuo Taoka) died in the early 1980s, his wife (Fumiko) took over as boss of Yamaguchi-gumi, albeit for a short time.

Yakuza have a complex organizational structure. There is an overall boss of the syndicate, the kumicho, and directly beneath him are the saiko komon (senior advisor) and so-honbucho (headquarters chief). The second in the chain of command is the wakagashira, who governs several gangs in a region with the help of a fuku-honbucho who is himself responsible for several gangs. The regional gangs themselves are governed by their local boss, the shateigashira.[26]

Each member's connection is ranked by the hierarchy of sakazuki (sake sharing). Kumicho is at the top and controls various saikō-komon (最高顧問, senior advisors). The saikō-komon control their own turfs in different areas or cities. They have their own underlings, including other underbosses, advisors, accountants, and enforcers.

Those who have received sake from oyabun are part of the immediate family and ranked in terms of elder or younger brothers. However, each kobun, in turn, can offer sakazuki as oyabun to his underling to form an affiliated organization, which might in turn form lower-ranked organizations. In the Yamaguchi-gumi, which controls some 2,500 businesses and 500 yakuza groups, there are fifth-rank subsidiary organizations.

Rituals[edit]

Yubitsume, also referred to as otoshimae, or the cutting off of one's finger, is a form of penance or apology. Upon a first offence, the transgressor must cut off the tip of his left little finger and give the severed portion to his boss. Sometimes an underboss may do this in penance to the oyabun if he wants to spare a member of his own gang from further retaliation. This practice has started to wane amongst the younger members, due to it being an easy identifier for police.[27]

Its origin stems from the traditional way of holding a Japanese sword. The bottom three fingers of each hand are used to grip the sword tightly, with the thumb and index fingers slightly loose. The removal of digits starting with the little finger and moving up the hand to the index finger progressively weakens a person's sword grip.

The idea is that a person with a weak sword grip then has to rely more on the group for protection—reducing individual action. In recent years, prosthetic fingertips have been developed to disguise this distinctive appearance.[23]

Many yakuza have full-body tattoos (including their genitalia). These tattoos, known as irezumi in Japan, are still often "hand-poked", that is, the ink is inserted beneath the skin using non-electrical, hand-made, and handheld tools with needles of sharpened bamboo or steel. The procedure is expensive and painful, and can take years to complete.[28]

When yakuza play Oicho-Kabu cards with each other, they often remove their shirts or open them up and drape them around their waists. This enables them to display their full-body tattoos to each other. This is one of the few times that yakuza display their tattoos to others, as they normally keep them concealed in public with long-sleeved and high-necked shirts. When new members join, they are often required to remove their trousers as well and reveal any lower body tattoos.[citation needed]

Syndicates[edit]

Number of members and quasi-members[edit]

The total number of yakuza members and quasi-members peaked at 184,100 in 1963, and then continued to decline due to police crackdowns.[7] The number of regular members decreased with the implementation of the Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members (暴力団員による不当な行為の防止等に関する法律) in 1992,[29] and the total number of members and quasi-members began to decline rapidly with the implementation of the yakuza exclusion ordinances in all 47 prefectures around 2010. Between 1990 and 2020, the total number of members and quasi-members decreased by 70 percent.[30]

The National Police Agency reported that Japanese yakuza organizations had 10,400 members and 10,000 quasi-members in 2023.[2]

Designated yakuza (Shitei Bōryokudan)[edit]

A designated yakuza (指定暴力団, Shitei Bōryokudan)[31] is a "particularly harmful" yakuza group[32] registered by the Prefectural Public Safety Commissions under the Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members (暴力団対策法, Bōryokudan Taisaku Hō) enacted in 1991.[33] Groups are designated as Shitei Bōryokudan (designated yakuza) if their members take advantage of the gang's influence to do business, are structured to have one leader, and have a large portion of their members hold criminal records.[6] After the Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members was enacted, many yakuza syndicates made efforts to restructure to appear more professional and legitimate.[6]

As of 2023, Under the Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members, the Prefectural Public Safety Commissions have registered 25 syndicates as the designated yakuza groups. Three of these organizations have more than 1,000 regular members, eight have more than 100, and 14 have less than 100. Fukuoka Prefecture has the largest number of designated yakuza groups among all of the prefectures, at 5; the Kudo-kai, the Taishu-kai, the Fukuhaku-kai, the Dojin-kai, and the Namikawa-kai.[2]

In August 2021, the Fukuoka District Court sentenced Satoru Nomura, the fifth head of Kudo-kai, to death for murder and attempted murder. This was the first death sentence handed down to a designated yakuza head. Kudo-kai is the only one of the designated yakuza to be designated as a especially dangerous designated yakuza (特定危険指定暴力団, Tokutei Kiken Shitei Bōryokudan), a more dangerous type of yakuza.[34]

Three largest syndicates and six major syndicates[edit]

As of 2023, the National Police Agency has designated Yamaguchi-gumi, Kobe Yamaguchi-gumi, Kizuna-kai, Ikeda-gumi (ja), Sumiyoshi-kai, and Inagawa-kai as Shuyō dantai (主要団体, major organizations) among the designated yakuza. These six organizations have a total of 7,700 members and 6,800 quasi-members, for a total of 14,500 members, or 71.1 percent of the total 20,400 yakuza members and quasi-members in Japan.[2]

Kobe Yamaguchi-gumi split off from Yamaguchi-gumi in August 2015, Kizuna-kai split off from Kobe Yamaguchi-gumi in April 2017, and Ikeda-gumi split off from Kobe Yamaguchi-gumi in July 2020. These Yamaguchi-gumi and the three organizations that split from them are fighting each other.[2]

In recent years, the three major yakuza syndicates have formed a loose alliance, and in April 2023, Kiyoshi Takayama, the wakagashira (second-in-command) of the Yamaguchi-gumi, Shuji Ogawa, the kaichō (chairman) of the Sumiyoshi-kai, and Kazuya Uchibori (ja), the kaichō of the Inagawa-kai, held a social gathering.[35]

| Principal families | Description | Mon (crest) |

|---|---|---|

| Yamaguchi-gumi (山口組, Yamaguchi-gumi) | The Yamaguchi-gumi is the largest yakuza family, accounting for 30% of all yakuza in Japan, with 3,500 members and 3,800 quasi-members as of 2023.[2] From its headquarters in Kobe, it directs criminal activities throughout Japan. It is also involved in operations in Asia and the United States. Shinobu Tsukasa, also known as Kenichi Shinoda, is the Yamaguchi-gumi's current oyabun. He follows an expansionist policy and has increased operations in Tokyo (which has not traditionally been the territory of the Yamaguchi-gumi.)

One of the best-known bosses of the Yamaguchi-gumi was Kazuo Taoka, the "Godfather of all Godfathers", who was responsible for the syndicate's massive growth and success during the 20th century.[36] |

"Yamabishi" (山菱) |

| Sumiyoshi-kai (住吉会) | The Sumiyoshi-kai is the second-largest yakuza family, with an estimated 2,200 members and 1,300 quasi-members as of 2023.[2] Sumiyoshi-kai is a confederation of smaller yakuza groups. Its current head (会長 kai-cho) is Shūji Ogawa. Structurally, Sumiyoshi-kai differs from its principal rival, the Yamaguchi-gumi, in that it functions like a federation. The chain of command is more relaxed, and its leadership is distributed among several other members. |

|

| Inagawa-kai (稲川会) | The Inagawa-kai is the third-largest yakuza family in Japan, with roughly 1,700 members and 1,200 quasi-members as of 2023.[2] It is based in the Tokyo-Yokohama area and was one of the first yakuza families to expand its operations outside of Japan. |

|

Current activities[edit]

Japan[edit]

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2013) |

The yakuza and its affiliated gangs control drug trafficking in Japan, especially methamphetamine.[37] While many yakuza syndicates, notably the Yamaguchi-gumi, officially forbid their members from engaging in drug trafficking, some other yakuza syndicates, like the Dojin-kai, are heavily involved in it.

Some yakuza groups are known to deal extensively in human trafficking.[38] In the Philippines Yakuza trick girls from impoverished villages into coming to Japan by promising them respectable jobs with good wages. Instead, they are forced into becoming sex workers and strippers.[39]

Yakuza frequently engaged in a unique form of Japanese extortion known as sōkaiya. In essence, this is a specialized form of protection racket. Instead of harassing small businesses, the Yakuza harass a stockholders' meeting of a larger corporation. Yakuza operatives obtain the right to attend by making a small purchase of stock, and then at the meeting physically intimidate other stockholders. The number of sōkaiya has decreased over the years, and in 2023 there were only about 150 sōkaiya, of whom 30 worked in groups and 120 worked alone.[40]

Yakuza also have ties to the Japanese real estate market and banking sector through jiageya. Jiageya specializes in inducing holders of small real estate to sell their property so that estate companies can carry out much larger development plans. The Japanese bubble economy of the 1980s is often blamed on real estate speculation by banking subsidiaries. After the collapse of the property bubble, a manager of a major bank in Nagoya was assassinated, prompting much speculation about the banking industry's indirect connection to the Japanese underworld.[41]

Yakuza have been known to make large investments in legitimate, mainstream companies. In 1989, Susumu Ishii, the Oyabun of the Inagawa-kai (a well-known yakuza group) bought US$255 million worth of Tokyo Kyuko Electric Railway's stock.[42] Japan's Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission has knowledge of more than 50 listed companies with ties to organized crime, and in March 2008, the Osaka Securities Exchange decided to review all listed companies and expel those with yakuza ties.[43]

As a matter of principle, theft is not recognized as a legitimate activity of yakuza. This is in line with the idea that their activities are semi-open; theft by definition would be a covert activity. More importantly, such an act would be considered a trespass by the community. Yakuza also usually do not conduct the actual business operation by themselves. Core business activities such as merchandising, loan sharking, or management of gambling houses are typically managed by non-yakuza who pay protection fees for their activities.

Numerous pieces of evidence tie yakuza to international criminal activity. There are many tattooed yakuza imprisoned in various Asian prisons for drug trafficking, arms smuggling, and other crimes. In 1997, one verified yakuza member was caught smuggling 4 kilograms (8.82 pounds) of heroin into Canada.[citation needed]

Because of their history as a legitimate feudal organization and their connection to the Japanese political system through the uyoku dantai (extreme right-wing political groups), yakuza are somewhat a part of the Japanese establishment, with six fan magazines reporting on their activities.[44] Yakuza involvement in politics functions similarly to that of a lobbying group, with them backing those who share in their opinions or beliefs.[45]

One study found that 1 in 10 adults under the age of 40 believed that the yakuza should be allowed to exist.[46]

In the 1980s in Fukuoka, a large conflict between the Yamaguchi-gumi and Dojin-kai groups known as the Yama-Ichi War spiraled out of control, and civilians were hurt. The police response was to mediate and force the yakuza bosses on both sides to publicly declare a truce.

Yakuza's aid in earthquakes[edit]

In 1995 Kobe earthquake, the Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza group, who are based in the area, mobilized to provide disaster relief services (including the use of a helicopter). Media reports contrasted this rapid response with the much slower pace at which the Japanese government's official relief efforts took place.[47][48]

Following the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011, the yakuza sent hundreds of trucks filled with food, water, blankets, and sanitary accessories to aid the people in the affected areas of the natural disaster.[46] CNN México said that although the yakuza operates through extortion and other violent methods, they "[moved] swiftly and quietly to provide aid to those most in need."[49]

United States[edit]

The presence of individuals affiliated with the yakuza in the United States has increased tremendously since the 1960s, and although much of their activity is concentrated in Hawaii, they have made their presence known in other parts of the country, especially in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as Seattle, Las Vegas, Arizona, Virginia, Chicago, and New York City.[50][51] The yakuza are said to use Hawaii as a midway station between Japan and mainland America, smuggling methamphetamine into the country and smuggling firearms back to Japan. They easily fit into the local population, since many tourists from Japan and other Asian countries visit the islands on a regular basis, and there is a large population of residents who are of full or partial Japanese descent. They also work with local gangs, funneling Japanese tourists to gambling parlors and brothels.[50]

In California, the yakuza have made alliances with local Korean gangs as well as Chinese triads and Vietnamese gangs. The yakuza identified these gangs as useful partners due to the constant stream of Vietnamese cafe shoot-outs and home invasion burglaries throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. In New York City, they appear to collect finder's fees from Russian, Irish and Italian gang members and businessmen for guiding Japanese tourists to gambling establishments, both legal and illegal.[50]

Handguns manufactured in the US account for a large share (33%) of handguns seized in Japan, followed by handguns manufactured in China (16%) and in the Philippines (10%). In 1990, a Smith & Wesson .38 caliber revolver that cost $275 in the US could sell for up to $4,000 in Tokyo.[citation needed]

In 2001, the FBI's representative in Tokyo arranged for Tadamasa Goto, the head of the group Goto-gumi, to receive a liver transplant at the UCLA Medical Center in the United States, in return for information of Yamaguchi-gumi operations in the US. This was done without prior consultation of the NPA. The journalist who uncovered the deal received threats from Goto and was given police protection in the US and in Japan.[43]

The FBI suspects that the yakuza were using various operations to launder money in the US as of 2008[update].[43]

Asia (outside Japan)[edit]

The yakuza have engaged in illegal activities in Southeast Asia since the 1960s; they are working there to develop sex tourism and drug trafficking.[52] This is the area where they are still the most active today.

In addition to their presence in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam, yakuza groups also operate in South Korea, China, Taiwan, and in the Pacific Islands (mainly Hawaii).[53]

Yakuza groups also have a presence in North Korea; in 2009, yakuza Yoshiaki Sawada was released from a North Korean prison after spending five years there attempting to bribe a North Korean official and smuggle drugs.[54]

Constituent members[edit]

According to a 2006 speech by Mitsuhiro Suganuma, a former officer of the Public Security Intelligence Agency, around 60 percent of yakuza members come from burakumin, the descendants of a feudal outcast class and approximately 30 percent of them are Japanese-born Koreans, and only 10 percent are from non-burakumin Japanese and Chinese ethnic groups.[55][56]

Burakumin[edit]

The burakumin is a group that Japanese society socially discriminates against, and its recorded history goes back to the Heian period in the 11th century. The burakumin are the descendants of outcast communities which originated in the pre-modern, especially the feudal era, mainly those people with occupations which are considered tainted because they are associated with death or ritual impurity, such as butchers, executioners, undertakers, or leather workers. They traditionally lived in their own secluded hamlets and villages away from other groups.

According to David E. Kaplan and Alec Dubro, burakumin account for about 70% of the members of Yamaguchi-gumi, the largest yakuza syndicate in Japan.[57]

Ethnic Koreans[edit]

While ethnic Koreans make up only 0.5% of the Japanese population, they are a prominent part of yakuza because they suffer discrimination in Japanese society along with the burakumin.[58][59] In the early 1990s, 18 of 90 top bosses of Inagawa-kai were ethnic Koreans. The Japanese National Police Agency suggested Koreans composed 10% of the yakuza proper and 70% of burakumin in the Yamaguchi-gumi.[58] Some of the representatives of the designated Bōryokudan are also Koreans.[60] The Korean significance had been an untouchable taboo in Japan and one of the reasons that the Japanese version of Kaplan and Dubro's Yakuza (1986) had not been published until 1991 with the deletion of Korean-related descriptions of the Yamaguchi-gumi.[61]

Japanese-born people of Korean ancestry who retain South Korean nationality are considered resident aliens and are embraced by the yakuza precisely because they fit the group's "outsider" image.[62][27]

Notable yakuza of Korean ancestry include Hisayuki Machii the founder of the Tosei-kai, Tokutaro Takayama the head of the 4th-generation Aizukotetsu-kai, Jiro Kiyota (1940–) the head of the 5th-generation Inagawa-kai, Shinichi Matsuyama (1927–) the head of the 5th-generation Kyokuto-kai and Hirofumi Hashimoto (1947–) the founder of the Kyokushinrengo-kai (affiliated with Yamaguchi-gumi, dissolved in 2019).

Law enforcement and indirect enforcement[edit]

Operation Summit[edit]

Between 1964 and 1965, the Japanese police carried out mass arrests of yakuza leaders and executives in what they called the Daiichiji chōjō sakusen (第一次頂上作戦, First Operation Summit) in response to public demands for the yakuza to be banished from society. As a result, crime declined and the number of arrested yakuza fell from about 59,000 in 1964 to 38,000 in 1967. The number of yakuza organizations and members also declined, from 5,216 organizations and 184,091 members in 1963 to 3,500 organizations and 139,089 members in 1969.[63] As a result, 1963, the year before the First Operation Summit was launched, was the peak of yakuza power.[7]

From around 1970, yakuza leaders and executives who had been imprisoned began to be released from prison, and yakuza organizations that had been disbanded during the First Operation Summit were revived and reorganized, leading the police to conduct the Second Operation Summit in 1970 and the Third Operation Summit in 1975. These series of police crackdowns led to a decline in the number of yakuza organizations and members, from 2957 organizations with 123,044 members in 1972 to 2517 organizations with 106,754 members in 1979. As a result, small yakuza organizations were forced to dissolve, and the total number of members decreased, but some members transferred to large yakuza organizations, so the number of members of large organizations actually increased during this period. The three major organizations, Yamaguchi-gumi, Sumiyoshi-kai, and Inagawa-kai, expanded during this period. During this period, Japan was in a recession following the energy crisis of the 1970s, and it became difficult for the yakuza to acquire sufficient financial resources through traditional methods alone, so it was inevitable that they would consolidate into large yakuza organizations with diverse or legal sources of funding.[7][64]

Anti-yakuza laws[edit]

The Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members (暴力団員による不当な行為の防止等に関する法律), passed in 1991 and enacted in 1992, was a landmark piece of legislation that cracked down on the yakuza. The law prohibited 27 acts by yakuza, including demanding hush money or donations, collecting debts and conducting land grabbing activities in an unjustified manner. The law also made it illegal to demand and collect so-called mikajime-ryō (protection racket) from downtown restaurants and bars, which were the yakuza's main source of funding. Police could issue two cease-and-desist orders to offenders who demanded mikajime-ryō, and could arrest offenders who still refused to comply. Until then, the yakuza had charged bouncer fees to restaurants and bars in their territory, especially those open at night, and made various threats, such as ramming dump trucks into businesses that refused, and business owners, fearing reprisals, had paid mikajime-ryō, but the new law resulted in more businesses refusing mikajime-ryō and the yakuza's financial resources were lost. In 1991, the yakuza had 63,800 members, but by 1992, when the new law took effect, the number had dropped sharply to about 56,600, then to about 48,000 in 1994 and 43,100 in 2001.[29][65]

Additional regulations can be found in a 2008 anti-yakuza amendment which allows prosecutors to place the blame on any yakuza-related crime on crime bosses. Specifically, the leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi has since been incarcerated and forced to pay upwards of 85 million yen in damages of several crimes committed by his gangsters, leading to the yakuza's dismissal of around 2,000 members per year; albeit, some analysts claim that these dismissals are part of the yakuza's collective attempt to regain a better reputation amongst the populace. Regardless, the yakuza's culture, too, has shifted towards a more secretive and far less public approach to crime, as many of their traditions have been reduced or erased to avoid being identified as yakuza.[66]

Beginning in 2009, led by agency chief Takaharu Ando, Japanese police began to crack down on the gangs. Yamaguchi-gumi's number two and Kodo-kai chief Kiyoshi Takayama was arrested in late 2010. In December 2010, police arrested Yamaguchi-gumi's alleged number three leader, Tadashi Irie.[67]

Yakuza exclusion ordinances[edit]

In addition to the anti-yakuza laws, the Yakuza exclusion ordinances enacted by each of Japan's 47 prefectures between 2009 and 2011 also contributed significantly to the decline of the yakuza.[68][30] Ordinances were enacted in Osaka and Tokyo in 2010 and 2011 to try to combat yakuza influence by making it illegal for any business to do business with the yakuza.[69][70] While the anti-yakuza laws prohibited the yakuza from making unreasonable demands on businesses and citizens, these ordinances prohibited businesses and citizens from offering benefits to the yakuza. This made it increasingly difficult for the yakuza to raise funds, as fewer businesses and citizens succumbed to the yakuza's threats and offered benefits to the yakuza, such as contracting work or paying money to the yakuza.[68][30] According to the media, encouraged by tougher anti-yakuza laws and yakuza exclusion ordinances, local governments and construction companies have begun to shun or ban yakuza activities or involvement in their communities or construction projects.[67]

In addition, these ordinances have made it difficult for yakuza members to lead normal civilian lives. The ordinances also require businesses and citizens to refuse to rent meeting rooms or parking spaces to the yakuza, or to print business cards with the name of yakuza organizations on them. Companies can now also refuse to open bank accounts, sign mobile phone contracts, credit card contracts, lease real estate, or process various loans for people identified as yakuza under the anti-yakuza laws, making it more difficult for yakuza to live in society.[68][71][72] Even companies that provide lifelines have become tough on the yakuza, with Osaka Gas terminating contracts if a contractor is discovered to be a yakuza. To prevent yakuza from nominally leaving the organization and signing contracts with companies, these ordinances allow companies to treat a person as a yakuza for five years even if he or she has nominally left the yakuza and become a civilian.[68][71][72]

Since 2011, regulations outlawing business with yakuza members, government-ordered audits of yakuza finances, and the enactment of yakuza exclusion ordinances have hastened a decline in yakuza membership. The number of yakuza members and quasi-members fell from 78,600 in 2010 to 25,900 in 2020.[68]

Outside Japan[edit]

Yakuza organizations also face pressure from the US government; in 2011, a federal executive order required financial institutions to freeze yakuza assets, and as of 2013, the U.S. Treasury Department had frozen about US$55,000 of yakuza holdings, including two Japan-issued American Express cards.[73]

Current situation[edit]

The number of yakuza members and quasi-members fell by about 70 percent in the 30 years between 1990, before the anti-yakuza law, and 2020, after the anti-yakuza laws and the yakuza exclusion ordinances took effect.[30]

On top of the already staggering anti-yakuza legislation, Japan's younger generation may be less inclined to gang-related activity, as modern society has made it easier especially for young men to gain even semi-legitimate jobs such as ownership in bars and massage parlors and pornography that can be more profitable than gang affiliation all while protecting themselves by abiding by the strict anti-yakuza laws.[66]

Citizens who take a stronger stance seem to also have taken action that does not lead to violent reactions from the yakuza. In Kyushu, although store owners initially were attacked by gang members, the region has reached stability after local business owners banned known yakuza and posted warnings against yakuza entering their premises.[74]

On August 24, 2021, Nomura Satoru became the first "designated yakuza" (指定暴力団, Shitei Bōryokudan) boss to be sentenced to death. Nomura was involved in one murder and assaults of three people. The presiding judge Adachi Ben of the Fukuoka District Court characterized the murders as extremely vicious attacks.[75] On March 12, 2024, the Fukuoka High Court overturned Nomura's death sentence and downgraded it to life imprisonment. The High Court found him not guilty of murder.[76]

Legacy[edit]

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Yakuza in society[edit]

The yakuza have had mixed relations with Japanese society. Despite their pariah status, some of their actions may be perceived to have positive effects on society. For example, they stop other criminal organizations from acting in their areas of operation.[77][unreliable source?] They have been known to provide relief in times of disaster. These actions have at times painted yakuza in a fairly positive light within Japan. The yakuza also attract membership from traditionally scorned minority groups, such as the Korean-Japanese.[78][79] However, gang wars and the use of violence as a tool have caused their approval to fall with the general public.[80]

Film[edit]

The yakuza have been in media and culture in many different fashions. Creating its own genre of movies within Japan's film industry, the portrayal of the yakuza mainly manifests in one of two archetypes; they are portrayed as either honorable and respectable men or as criminals who use fear and violence as their means of operation.[81] Movies like Battles Without Honor and Humanity and Dead or Alive portray some of the members as violent criminals, with the focus being on the violence, while other movies focus more on the "business" side of the yakuza.

The 1992 film Minbo, a satirical view of yakuza activities, resulted in retaliation against the director, as real-life yakuza gangsters attacked the director Juzo Itami shortly after the release of the film.[82]

Yakuza films have also been popular in the Western market with films such as the 1975 film The Yakuza, the 1989 film Black Rain and The Punisher, the 2005 film Into the Sun, 2013's The Wolverine, 2018 film The Outsider, and Snake Eyes in 2021.

Television[edit]

The yakuza feature prominently in the 2015 American dystopian series The Man in the High Castle. They are also the basis for the 2019 BBC TV Series Giri/Haji, which features a character whose life is put in danger after he comes under suspicion for a murder tied to the yakuza. The 2022 HBO Max series Tokyo Vice explores the dealings of the yakuza from the perspective of an American reporter Jake Adelstein.

Video games[edit]

The video game series Like A Dragon, formerly known as Yakuza outside of Japan, launched in 2005, portrays the actions of several different ranking members of the yakuza, as well as criminal associates such as dirty cops and loan sharks. The series addresses some of the same themes as the yakuza genre of film does, like violence, honor, politics of the syndicates, and the social status of the yakuza in Japan. The series has been successful, spawning sequels, spin-offs, a live-action movie and a web TV series.

Grand Theft Auto III features a yakuza clan that assists the protagonist in the second and third act after they cut their ties with the Mafia. The yakuza derive most of their income from a casino, Kenji's, and are currently fighting to keep other gangs from peddling drugs in their territory while seeking to protect their activities from police interference. Towards the end of the third act, the player assassinates the leader of the clan, and the other members are later executed by Colombian gangsters. In Grand Theft Auto III's prequel, Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories, the yakuza play a major role in the storyline. In Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, the yakuza are mentioned, presumably operating in Vice City.

Hitman 2: Silent Assassin features a mission set in Japan that sees Agent 47 assassinating the son of a wealthy arms dealer during his dinner meeting with a yakuza boss at his private estate. A mission in the 2016 game, Hitman, set at a secluded mountaintop hospital, features a notorious yakuza lawyer and fixer as one of two targets to be assassinated.

Manga, anime and television dramas[edit]

- Stop!! Hibari-kun!: manga (1981–1983), anime (1983–1984). The story focuses on Kōsaku Sakamoto, a high school student who goes to live with yakuza boss Ibari Ōzora and his four children—Tsugumi, Tsubame, Hibari and Suzume—after the death of his mother. Kōsaku is shocked to learn that Hibari, who looks and behaves as a girl, is male.

- Gokusen: manga (2000), drama (2002, 2005 and 2008) and anime (2004). The heiress of a clan becomes a teacher in a difficult high school and is assigned a class of delinquents, the 3-D. She will teach them mathematics, while gradually getting involved in several other levels, going so far as to get her students out of a bad situation by sometimes using her skills as heir to the clan.

- My Boss My Hero: Film stock (2001), drama (2002). A young gang leader, who seems to be too stupid to do his job, misses a big deal because he cannot count correctly, and on the other hand, is practically illiterate. In order to access the succession of the clan, his father then forces him to return to high school, to obtain his diploma. He must not reveal his membership in the yakuza, under penalty of being immediately excluded.

- Twittering Birds Never Fly: manga of the shōnen-ai genre (2011–?). Yashiro, a totally depraved masochist, boss of a yakuza clan and the Shinsei finance company, hires Chikara Dômeki, a secretive and not very talkative man, as his bodyguard. While Yashiro would like to take advantage of Dômeki's body, the latter is helpless.[83]

- Like the Beast: manga, yaoi (2008). Tomoharu Ueda, a police officer in a small local post, meets Aki Gotôda, son of the leader of a yakuza clan, in pursuit of an underwear thief. The next morning, Aki shows up at his house to thank him for his help and finds himself making a declaration of love for him. Taken aback, Ueda replies that it is better that they get to know each other, but that's without counting Aki's stubbornness, ready to do anything to achieve his ends.

- Odd Taxi: anime, manga (2021). A taxi driver becomes entangled in the rivalry of competing kobun and uses his position to undermine the local yakuza organization.

Several manga by Ryoichi Ikegami are located in the middle of the Japanese underworld:

- Sanctuary (1990): Hôjô and Asami, childhood friends, have only one goal: to give the Japanese back a taste of life, and to shake up the country. For this, they decide to climb the ladder of power, one in the light, as a politician, the other in the shadows, as yakuza.

- Heat (1999): Tatsumi Karasawa is the owner of a club in Tokyo who plans to expand his business. He gives a hard time not only to the police but also to the yakuza, of which he manages, however, to rally a certain number at his side.

- Nisekoi (2014): Nisekoi follows high school students Raku Ichijo, the son of a leader in the yakuza faction Shuei-gumi, and Chitoge Kirisaki, the daughter of a boss in a rival gang known as Muchi-Konkai.

[edit]

| English | Japanese Rōmaji |

|---|---|

| association/society | -kai |

| behind-the-scenes fixer, godfather, or power broker (lit. "black curtain") | kuromaku |

| boss (lit. "parent role") | oyabun |

| gambler | bakuto |

| gang/company | -gumi |

| hoodlum/ruffian | gurentai |

| loan sharks (lit. "salary man financiers") | sarakin |

| motorcycle gang | bosozoku |

| nightclubs, bars, restaurants, etc. (lit. "water business") | mizu shobai |

| outcasts (by birth) | burakumin |

| peddlers, street stall operators | tekiya |

| ritual cutting of the joint of the little finger to atone for a mistake | yubitsume |

| ritual sharing of sake to form a binding relationship; rooted in Shinto tradition | sakazuki |

| underling (lit. "child role") | kobun |

| violence group | bōryokudan |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Japanese Organised Crime in Australia".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Organized Crime Situation 2023" (PDF). National Police Agency. pp. 2–6, 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Britannica Academic, s.v. "Yakuza", accessed 30 September 2018, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/yakuza/77739.

- ^ Bosmia, Anand N.; Griessenauer, Christoph J.; Tubbs, R. Shane (2014). "Yubitsume: ritualistic self-amputation of proximal digits among the Yakuza". Journal of Injury and Violence Research. 6 (2): 54–56. doi:10.5249/jivr.v6i2.489. PMC 4009169. PMID 24284812.

- ^ "Feeling the heat; The yakuza". The Economist. Vol. 390, no. 8620. 28 February 2009. Gale A194486438.

- ^ a b c Reilly, Edward (1 January 2014). "Criminalizing Yakuza Membership: A Comparative Study of the Anti-Boryokudan Law". Washington University Global Studies Law Review. 13 (4): 801–829. Gale A418089219.

- ^ a b c d 第4章 暴力団総合対策の推進. National Police Agency. 1999.

- ^ Hill, Peter (February 2004). "The Changing Face of the Yakuza". Global Crime. 6 (1): 97–116. doi:10.1080/1744057042000297007. S2CID 153495517.

- ^ 暴力団勢力、2万2400人 18年連続減少 組員、平均年齢上昇. The Asahi Shimbun. 27 March 2023

- ^ a b Shikata, Ko (October 2006). "Yakuza – organized crime in Japan". Journal of Money Laundering Control. 9 (4): 416–421. doi:10.1108/13685200610707653. ProQuest 235850419.

- ^ Hessler, Peter (2 January 2012). "All Due Respect". The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

The name refers to an unlucky hand at cards—yakuza means "eight-nine-three"—and bluffing has always been part of the image. Many gangsters are Korean-Japanese or members of other minority groups that traditionally have been scorned.

- ^ "Yakuza" definition. Kotobank (in Japanese)

- ^ Dubro, A.; Kaplan, David E. (1986). Yakuza: The Explosive Account of Japan's Criminal Underworld. Da Capo Press. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0-201-11151-4.

- ^ Joy, Alicia. "A Brief History of the Yakuza Organization". Culture Trip. Last modified 31 October 2016. https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/a-brief-history-of-the-yakuza-organization/ Archived 1 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Raz, Jacob. "Insider Outsider: The Way of the Yakuza." Kyoto Journal. Last modified 17 April 2011. https://kyotojournal.org/society/insider-outsider/.

- ^ Dubro, A.; Kaplan, David E. (1986). Yakuza: The Explosive Account of Japan's Criminal Underworld. Da Capo Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-201-11151-4.

- ^ Kaplan, David E.; Dubro, Alec (2012). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld (25th Anniversary ed.). the University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520215627.

- ^ "Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures". National Diet Library, Japan. 22 May 2007. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019.

- ^ Johnson, David T. (2002). The Japanese way of justice: prosecuting crime in Japan. Oxford [England] ; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195119862.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Baradel, Martina (2 January 2021). "Yakuza Grey: The Shrinking of the Il/legal Nexus and its Repercussions on Japanese Organised Crime". Global Crime. 22 (1): 74–91. doi:10.1080/17440572.2020.1813114. ISSN 1744-0572.

- ^ Siniawer, E. M. (1 March 2012). "Befitting Bedfellows: Yakuza and the State in Modern Japan". Journal of Social History. 45 (3): 623–641. doi:10.1093/jsh/shr120. ISSN 0022-4529.

- ^ High concentration of, Yakuza within Fukuoka (20 February 2018). "Fukuoka to offer financial help for gangsters trying to leave crime syndicates". www.japantimes.co.jp. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b Bruno, Anthony. "The Yakuza – Oyabun-Kobun, Father-Child". truTV. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ Ronald Philip Dore (8 March 2015). Aspects of Social Change in Modern Japan. Princeton University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4008-7206-0.

- ^ Luis Frois SJ (14 March 2014). The First European Description of Japan, 1585: A Critical English-Language Edition of Striking Contrasts in the Customs of Europe and Japan by Luis Frois, S.J. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-317-91781-6.

- ^ "The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia –The Crime Library – Crime Library on truTV.com".

- ^ a b "The Yakuza: Inside Japan's murky criminal underworld". CNN.

- ^ Japanorama, BBC Three, Series 2, Episode 3, first aired 21 September 2006

- ^ a b "「億単位のカネが簡単に集まった」暴対法から約30年…指定暴力団の幹部が明かす「バブル時代の暴力団のヤバすぎる実態」". Kodansha. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d "30年で構成員7割減…令和時代 暴力団はいま". NHK. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Police of Japan 2011, Criminal Investigation : 2. Fight Against Organized Crime" Archived 10 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, December 2009, National Police Agency

- ^ "Act on Prevention of Unjust Acts by Organized Crime Group Members" Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Fukuoka Prefectural Center for the Elimination of Boryokudan (in Japanese)

- ^ "Boryokudan Comprehensive Measures – The Condition of the Boryokudan", December 2010, Hokkaido Prefectural Police (in Japanese)

- ^ 工藤会と"91人の証言者" 暴力団トップ死刑判決の内幕. NHK. 5 October 2021

- ^ 六代目山口組髙山清司若頭、住吉会&稲川会トップと"ヤクザサミット"開催 緊張感漂う内部写真公開. Yahoo Japan News. 13 April 2023

- ^ Britannica, Encyclopedia. "Taoka Kazuo, Japanese crime boss". www.britannica.com. The editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Vorobyov, Niko (2019) Dopeworld. Hodder, UK. p. 91–93

- ^ "HumanTrafficking.org, "Human Trafficking in Japan"". Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia – The Crime Library – Crime Library on truTV.com".

- ^ "Organized Crime Situation 2023" (PDF). National Police Agency. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "US clamps down on Japanese Yakuza mafia". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Kaplan, David E.; Dubro, Alec (2012). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27490-7.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Jake Adelstein. This Mob Is Big in Japan, The Washington Post, 11 May 2008

- ^ "The Yakuza's Ties to the Japanese Right Wing". Vice Today.

- ^ "The Yakuza Lobby". Foreign Policy.

- ^ a b Adelstein, Jake (18 March 2011). "Japanese Yakuza Aid Earthquake Relief Efforts". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Sterngold, James (22 January 1995), "Quake in Japan: Gangsters; Gang in Kobe Organizes Aid for People in Quake", The New York Times.

- ^ Sawada, Yasuyuki; Shimizutani, Satoshi (March 2008). "How Do People Cope with Natural Disasters? Evidence from the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) Earthquake in 1995". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 40 (2–3): 463–488. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00122.x.

- ^ "La mafia japonesa de los 'yakuza' envía alimentos a las víctimas del sismo". CNN México (in Spanish). 25 March 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Yakuza Archived 11 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Crimelibrary.com

- ^ Kaplan, David E.; Dubro, Alec (2003). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21562-7.[page needed]

- ^ Bouissou, Jean-Marie (1999). "Le marché des services criminels au Japon. Les yakuzas et l'État" [The criminal services market in Japan. The Yakuza and the State] (PDF). Critique Internationale (in French). 3 (1): 155–174. doi:10.3406/criti.1999.1602.

- ^ Jean-François Gayraud, Le Monde des mafias, édition 2008, p. 104

- ^ Yakuza returns after five years in North Korea jail on drug charge 2009-01-16 The Japan Times

- ^ "Mitsuhiro Suganuma, "Japan's Intelligence Services"". The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Capital punishment – Japan's Yakuza Vie for Control of Tokyo" (PDF). Jane's Intelligence Review: 4. December 2009.

Around 60% of yakuza members come from burakumin, the descendants of a feudal outcast class, according to a 2006 speech by Mitsuhiro Suganuma, a former officer of the Public Security Intelligence Agency. He also said that approximately 30% of them are Japanese-born Koreans, and only 10% are from non-burakumin Japanese and Chinese ethnic groups.

- ^ Dubro, A.; Kaplan, David E. (1986). Yakuza: The Explosive Account of Japan's Criminal Underworld. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-201-11151-4.[page needed]

- ^ a b Kaplan, David E.; Dubro, Alec (2003). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-520-21562-7.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (30 November 1995). "Japan's Invisible Minority: Better Off Than in Past, but StillOutcasts". The New York Times.

- ^ (in Japanese) "Boryokudan Situation in the Early 2007", National Police Agency, 2007, p. 22. See also Bōryokudan#Designated bōryokudan.

- ^ Kaplan and Dubro (2003) Preface to the new edition.

- ^ Bruno, A. (2007). The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia. CrimeLibrary: Time Warner

- ^ "White Paper on Crime 1989 3 頂上作戦とその影響(昭和30年代末~40年代前半)". Ministry of Justice (Japan). Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "White Paper on Crime 1989 4 広域化・寡占化による再編の時代(昭和40年代後半~50年代前半)". Ministry of Justice (Japan). Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "暴力的要求行為の禁止内容". National Center for Removal of Criminal Organizations. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b "21st-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends in Organized Crime in Japan ~Part 1 21 ――". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b Zeller, Frank (AFP-Jiji), "Yakuza served notice days of looking the other way are over," Japan Times, 26 January 2011, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "「早くやめておけば」あえぐ組員、強まる排除 「暴排」条例の10年". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Botting, Geoff, "Average Joe could be collateral damage in war against yakuza", Japan Times, 16 October 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Schreiber, Mark, "Anti-Yakuza Laws are Taking their Toll", Japan Times, 4 March 2012, p. 9.

- ^ a b "元暴5年条項とは?定義や反社会的勢力排除に必要な理由を解説". Socialwire Co.,Ltd. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b "暴力団から足を洗って5年以上なのに、どうして銀行口座つくれないの? 元組員が「不合理な差別」と提訴". Tokyo Shimbun. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Yakuza Bosses Whacked by Regulators Freezing AmEx Cards". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Citizens battle Kudo-kai yakuza gang to take back their streets | The Asahi Shimbun: Breaking News, Japan News and Analysis". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ RJ Endra (24 August 2021). "Yakuza boss is first ever to be sentenced to death in Japan". The Japan Story. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Japanese high court overturns death sentence against yakuza gang leader". NHK. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "The Yakuza's Impact On Japanese Society | ipl.org". www.ipl.org. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Martin, Alexander (30 November 1999). "5 Things to Know About Japan's Yakuza". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Gragert, Lt. Bruce (25 August 2010). "Yakuza: The Warlords of Japanese Organized Crime". Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law. 4 (1). Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Where Have Japan's Yakuza Gone?". Daily Beast.

- ^ "Yakuza: Kind-hearted criminals or monsters in suits?". Japan Today. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Reposted: The high price of writing about anti-social forces – and those who pay. 猪狩先生を弔う日々 : Japan Subculture Research Center". japansubculture.com. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Serie –Twittering birds never fly". taifu-comics.com. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bruno, A. (2007). "The Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia" CrimeLibrary: Time Warner

- Blancke, Stephan. ed. (2015). East Asian Intelligence and Organised Crime. China – Japan – North Korea – South Korea – Mongolia Berlin: Verlag Dr. Köster (ISBN 978-3895748882)

- Kaplan, David, Dubro Alec. (1986). Yakuza Addison-Wesley (ISBN 0-201-11151-9)

- Kaplan, David, Dubro Alec. (2003). Yakuza: Expanded Edition University of California Press (ISBN 0-520-21562-1)

- Hill, Peter B.E. (2003). The Japanese Mafia: Yakuza, Law, and the State Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-925752-3)

- Johnson, David T. (2001). The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-511986-X)

- Miyazaki, Manabu. (2005) Toppamono: Outlaw. Radical. Suspect. My Life in Japan's Underworld Kotan Publishing (ISBN 0-9701716-2-5)

- Seymour, Christopher. (1996). Yakuza Diary Atlantic Monthly Press (ISBN 0-87113-604-X)

- Saga, Junichi., Bester, John. (1991) Confessions of a Yakuza: A Life in Japan's Underworld Kodansha America

- Schilling, Mark. (2003). The Yakuza Movie Book Stone Bridge Press (ISBN 1-880656-76-0)

- Sterling, Claire. (1994). Thieves' World Simon & Schuster (ISBN 0-671-74997-8)

- Sho Fumimura (Writer), Ryoichi Ikegami (Artist). (Series 1993–1997) "Sanctuary" Viz Communications Inc (Vol 1: ISBN 0-929279-97-2; Vol 2:ISBN 0-929279-99-9; Vol 3: ISBN 1-56931-042-4; Vol 4: ISBN 1-56931-039-4; Vol 5: ISBN 1-56931-112-9; Vol 6: ISBN 1-56931-199-4; Vol 7: ISBN 1-56931-184-6; Vol 8: ISBN 1-56931-207-9; Vol 9: ISBN 1-56931-235-4)

- Tendo, Shoko (2007). Yakuza Moon: Memoirs of a Gangster's Daughter Kodansha International [1] (ISBN 978-4-7700-3042-9)

- Young Yakuza. Dir. Jean-Pierre Limosin. Cinema Epoch, 2007.

External links[edit]

- The Secret Lives of Yakuza Women – BBC Reel (Video)

- 101 East – Battling the Yakuza – Al Jazeera (Video)

- FBI What We Investigate – Asian Transnational Organized Crime Groups

- Yakuza Portal site

- Blood Ties: Yakuza Daughter Lifts Lid on Hidden Hell of Gangsters' families

- Crime Library: Yakuza

- Japanese Mayor Shot Dead; CBS News, 17 April 2007

- Yakuza: The Japanese Mafia

- Yakuza: Kind-Hearted Criminals or Monsters in Suits?

- Yakuza

- 17th-century establishments in Japan

- Organizations established in the 17th century

- Japanese secret societies

- Secret societies related to organized crime

- Criminal subcultures

- Japanese subcultures

- Culture of Japan

- Organized crime by ethnic or national origin

- Transnational organized crime

- Organized crime groups in Japan

- Organized crime groups in the United States

- Gangs in Hawaii

- Gangs in Los Angeles

- Gangs in New York City

- Gangs in San Francisco

- Anti-communist organizations in Japan