William the Silent

| William the Silent | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Adriaen Thomasz. Key, c. 1570–1584 | |

| Prince of Orange | |

| Reign | 15 July 1544 – 10 July 1584 |

| Predecessor | René |

| Successor | Philip William |

| Stadtholder of Friesland | |

| In office 1580–1584 | |

| Preceded by | George de Lalaing |

| Succeeded by | William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg |

| Stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland | |

| In office 1572–1584 | |

| Preceded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Succeeded by | Maurice of Nassau |

| In office 1559–1567 | |

| Monarch | Philip II of Spain |

| Preceded by | Maximilian of Burgundy |

| Succeeded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Stadtholder of Utrecht | |

| In office 1572–1584 | |

| Preceded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Succeeded by | Adolf van Nieuwenaar |

| In office 1559–1567 | |

| Monarch | Philip II of Spain |

| Preceded by | Maximilian of Burgundy |

| Succeeded by | Maximilien de Hénin-Liétard |

| Born | 24 April 1533 Dillenburg, County of Nassau, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 10 July 1584 (aged 51) Delft, County of Holland, Dutch Republic |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | 16 |

| House | Born into the House of Nassau; founder of the Orange-Nassau branch; ancestor of the monarchy of the Netherlands |

| Father | William I, Count of Nassau-Siegen |

| Mother | Juliana of Stolberg-Werningerode |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | |

William the Silent or William the Taciturn (Dutch: Willem de Zwijger;[1][2] 24 April 1533 – 10 July 1584), more commonly known in the Netherlands[3][4] as William of Orange (Dutch: Willem van Oranje), was the leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish Habsburgs that set off the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) and resulted in the formal independence of the United Provinces in 1648. Born into the House of Nassau, he became Prince of Orange in 1544 and is thereby the founder of the Orange-Nassau branch and the ancestor of the monarchy of the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, he is also known as Father of the Fatherland (Latin: Pater Patriae; Dutch: Vader des Vaderlands).

A wealthy nobleman, William originally served the Habsburgs as a member of the court of Margaret of Parma, governor of the Spanish Netherlands. Unhappy with the centralisation of political power away from the local estates and with the Spanish persecution of Dutch Protestants, William joined the Dutch uprising and turned against his former masters. The most influential and politically capable of the rebels, he led the Dutch to several successes in the fight against the Spanish. Declared an outlaw by the Spanish king in 1580, he was assassinated by Balthasar Gérard in Delft in 1584.

Early life and education[edit]

William was born on 24 April 1533 at Dillenburg Castle in the County of Nassau-Dillenburg, in the Holy Roman Empire (now in Hesse, German Federal Republic). He was the eldest son of Count William I of Nassau-Siegen and his second wife, Countess Juliana of Stolberg. William's father had one surviving daughter by his previous marriage to Walburga of Egmont, and his mother had four surviving children by her previous marriage to Philipp II, Count of Hanau-Münzenberg. His parents had twelve children together, of whom William was the eldest; he had four younger brothers and seven younger sisters. The family was religiously devout and William was raised a Lutheran.[5]

In 1544, William's agnatic first cousin, René of Châlon, Prince of Orange, died in the siege of St Dizier, childless. In his testament, René of Chalon named William the heir to all his estates and titles, including that of Prince of Orange, on the condition that he receive a Roman Catholic education.[5] William's father acquiesced to this condition on behalf of his 11-year-old son, and this was the founding of the House of Orange-Nassau. Besides the Principality of Orange (located today in France) and significant lands in Germany, William also inherited vast estates in the Low Countries (present-day Netherlands and Belgium) from his cousin. Because of William's young age, Emperor Charles V, who was the overlord of most of these estates, served as regent until William was old enough to rule them himself.

William was sent to the Netherlands to receive the required Roman Catholic education, first at the family's estate in Breda and later in Brussels, under the supervision of the Emperor's sister Mary of Hungary, governor of the Habsburg Netherlands (Seventeen Provinces). In Brussels, he was taught foreign languages and received a military and diplomatic education[6] under the direction of Jérôme Perrenot de Champagney, brother of Cardinal de Granvelle.

On 6 July 1551, William married Anna, daughter and heir of Maximiliaan van Egmond, an important Dutch nobleman, a match that had been secured by Charles V.[5] Anna's father had died in 1548, and therefore William became Lord of Egmond and Count of Buren upon his wedding day. The marriage was a happy one and produced three children, one of whom died in infancy. Anna died on 24 March 1558, aged 25, leaving William much grieved.

Career[edit]

Imperial favourite[edit]

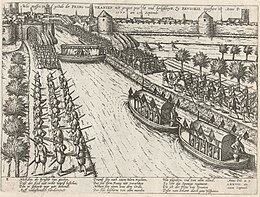

Being a ward of Charles V and having received his education under the tutelage of the Emperor's sister Mary, William came under the particular attention of the imperial family, and became a favourite. He was appointed captain in the cavalry in 1551 and received rapid promotion thereafter, becoming commander of one of the Emperor's armies at the age of 22. This was in 1555, when Charles sent him to Bayonne with an army of 20,000 to take the city in a siege from the French. William was also made a member of the Raad van State, the highest political advisory council in the Netherlands.[7] It was in November of the same year (1555) that the gout-afflicted Emperor Charles leaned on William's shoulder during the ceremony when he abdicated the Low Countries in favour of his son, Philip II of Spain.[8] William was also selected to carry the insignia of the Holy Roman Empire to Charles's brother Ferdinand, when Charles resigned the imperial crown in 1556 and was one of the Spanish signatories for the April 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis.[5]

In 1559, Philip II appointed William stadtholder (governor) of the provinces of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, thereby greatly increasing his political power.[9] A stadtholdership over Franche-Comté followed in 1561.

From politician to rebel[edit]

Although he never directly opposed the Spanish king, William soon became one of the most prominent members of the opposition in the Council of State, together with Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn, and Lamoral, Count of Egmont. They were mainly seeking more political power for themselves against the de facto government of Count Berlaymont, Granvelle and Viglius of Aytta, but also for the Dutch nobility and, ostensibly, for the Estates, and complained that too many Spaniards were involved in governing the Netherlands. William was also dissatisfied with the increasing persecution of Protestants in the Netherlands. Brought up as a Lutheran and later a Catholic, William was very religious but was still a proponent of freedom of religion for all people. The activity of the Inquisition in the Netherlands, directed by Cardinal Granvelle, prime minister to the new governor Margaret of Parma (1522–1583, natural half-sister to Philip II), increased opposition to Spanish rule among the then mostly Catholic population of the Netherlands. Lastly, the opposition wished to see an end to the presence of Spanish troops.

According to the Apology, William's letter of justification, which was published and read to the States General in December 1580, his resolve to expel the Spaniards from the Netherlands had originated when, in the summer of 1559, he and the Duke of Alba had been sent to France as hostages for the proper fulfilment of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis following the Hispano-French war. During his stay in Paris, on a hunting trip to the Bois de Vincennes, King Henry II of France started to discuss with William a secret understanding between Philip II and himself aimed at the violent extermination of Protestantism in France, the Netherlands "and the entire Christian world".[11] The understanding was being negotiated by Alba, and Henry had assumed, incorrectly, that William was aware of it. At the time, William did not contradict the king's assumption, but he had decided for himself that he would not allow the slaughter of "so many honourable people", especially in the Netherlands, for which he felt a strong compassion.[12]

On 25 August 1561, William of Orange married for the second time. His new wife, Anna of Saxony, was described by contemporaries as "self-absorbed, weak, assertive, and cruel", and it is generally assumed that William married her to gain more influence in Saxony, Hesse and the Palatinate.[13] The couple had five children. The marriage used Lutheran rites, and marked the beginning of a gradual change in his religious opinions, which was to lead William to revert to Lutheranism and eventually moderate Calvinism. Still, he remained tolerant of other religious opinions.[5]

Up to this time William's life had been marked by lavish display and extravagance. He surrounded himself with a retinue of young noblemen and dependents and kept open house in his magnificent Nassau palace at Brussels. Consequently, the revenue of his vast estates was not sufficient to prevent him being crippled by debt. But after his return from France, a change began to come over William. Philip made him councillor of state, knight of the Golden Fleece, and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, but there was a latent antagonism between the natures of the two men.[5]

Up to 1564, any criticism of governmental measures voiced by William and the other members of the opposition had ostensibly been directed at Granvelle; however, after the latter's departure early that year, William, who may have found increasing confidence in his alliance with the Protestant princes of Germany following his second marriage,[14] began to openly criticise the King's anti-Protestant politics. In August of that year, Philip issued an order for carrying out the decrees of the anti-Protestant Council of Trent.[5] But, in an iconic speech to the Council of State, William to the shock of his audience justified his conflict with Philip by saying that, even though he had decided for himself to keep to the Catholic faith (at the time), he could not agree that monarchs should rule over the souls of their subjects and take from them their freedom of belief and religion.[15]

In early 1565, a large group of lesser noblemen, including William's younger brother Louis, formed the Confederacy of Noblemen. On 5 April, they offered a petition to Margaret of Parma, requesting an end to the persecution of Protestants. From August to October 1566, a wave of iconoclasm (known as the Beeldenstorm) spread through the Low Countries. Calvinists (the major Protestant denomination), Anabaptists, and Mennonites, angered by Catholic oppression and theologically opposed to the Catholic use of images of saints (which in their eyes conflicted with the Second Commandment), destroyed statues in hundreds of churches and monasteries throughout the Netherlands.

Following the Beeldenstorm, unrest in the Netherlands grew, and Margaret agreed to grant the wishes of the Confederacy, provided the noblemen would help to restore order. She also allowed more important noblemen, including William of Orange, to assist the Confederacy, and William went to Antwerp where he succeeded in quelling the riot. In late 1566, and early 1567, it became clear that she would not be allowed to fulfil her promises, and when several minor rebellions failed, many Calvinists and Lutherans fled the country. Following the announcement that Philip II, unhappy with the situation in the Netherlands, would dispatch his loyal general Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, or Alva (also known as "The Iron Duke"), to restore order, William laid down his functions and retreated to his native Nassau in April 1567. He had been financially involved with several of the rebellions.

After his arrival in August 1567, Alba established the Council of Troubles (known to the people as the Council of Blood) to judge those involved in the rebellion and the iconoclasm. William was one of the 10,000 to be summoned before the council, but he failed to appear. He was subsequently declared an outlaw, and his properties were confiscated. As one of the most prominent and popular politicians of the Netherlands, William of Orange emerged as the leader of armed resistance. He financed the Watergeuzen, refugee Protestants who formed bands of corsairs and raided the coastal cities of the Netherlands (often killing Spanish and Dutch alike). He also raised an army, consisting mostly of German mercenaries, to fight Alba on land. William allied with the French Huguenots, following the end of the second Religious War in France when they had troops to spare.[16] Led by his brother Louis, the army invaded the northern Netherlands in 1568. However, the plan failed almost from the start. The Huguenots were defeated by French royal troops before they could invade, and a small force under Jean de Villers was captured within two days. Villers gave all the plans of the campaign to the Spanish following his capture.[17] On 23 May, the army under the command of Louis won the Battle of Heiligerlee in the northern province of Groningen against a Spanish army led by the stadtholder of the northern provinces, Jean de Ligne, Duke of Arenberg. Arenberg was killed in the battle, as was William's brother Adolf. Alba countered by killing a number of convicted noblemen (including the Counts of Egmont and Hoorn on 6 June), and then by leading an expedition to Groningen. There, he annihilated Louis' forces on German territory in the Battle of Jemmingen on 21 July, although Louis managed to escape.[18] These two battles are now considered to be the start of the Eighty Years' War.

War[edit]

In October 1568, William responded by leading a large army into Brabant, but Alba carefully avoided a decisive confrontation, expecting the army to fall apart quickly. As William advanced, disorder broke out in his army, and with winter approaching and money running out, William turned back and crossed into France.[19] William made several more plans to invade in the next few years, but little came of them, since he lacked support and money. He remained popular with the public, in part through an extensive propaganda campaign conducted through pamphlets. One of his most important claims, with which he attempted to justify his actions, was that he was not fighting the rightful ruler of the land, the King of Spain, but only the inadequate rule of the foreign governors in the Netherlands, and the presence of foreign soldiers.

On 22 August 1571, his second wife Anna gave birth to a daughter, named Christina von Dietz, and fathered by Jan Rubens, best known as the father of painter Peter Paul Rubens; Jan Rubens had been sent by Anna's uncle in 1570 to manage her finances.[20] Later that year, William had this marriage legally dissolved on the grounds that Anna was insane.

On 1 April 1572, a group known as the Watergeuzen ("Sea Beggars") captured the city of Brielle, which had been left unattended by the Spanish garrison. Contrary to their normal "hit and run" tactics, they occupied the town and claimed it for the prince by raising the Prince of Orange's flag above the city.[21] This event was followed by other cities opening their gates for the Watergeuzen, and soon most cities in Holland and Zeeland were in the hands of the rebels, notable exceptions being Amsterdam and Middelburg. The rebel cities then called a meeting of the Staten Generaal (which they were technically unqualified to do), and reinstated William as the stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland.

Concurrently, rebel armies captured cities throughout the entire country, from Deventer to Mons. William himself then advanced with his own army and marched into several cities in the south, including Roermond and Leuven. William had counted on intervention from the Huguenots as well, but this plan was thwarted after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre on 24 August, which signalled the start of a wave of violence against the Huguenots. After a successful Spanish attack on his army, William had to flee and he retreated to Enkhuizen, in Holland. The Spanish then organised countermeasures, and sacked several rebel cities, sometimes massacring their inhabitants, such as in Mechelen or Zutphen. They had more trouble with the cities in Holland, where they took Haarlem after seven months and a loss of 8,000 soldiers, and they had to break off their siege of Alkmaar.

In 1573, William joined the Calvinist Church.[22] He appointed a Calvinist theologian, Jean Taffin (1573–1581) as his court preacher. Taffin was later joined by Pierre Loyseleur de Villiers (1577–1584), who also became an important political advisor to the prince.

In 1574, William's armies won several minor battles, including several naval encounters. The Spanish, led by Don Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens since Philip replaced Alba in 1573, also had their successes. Their decisive victory in the Battle of Mookerheyde in the south east, on the Meuse embankment, on 14 April cost the lives of two of William's brothers, Louis and Henry. Requesens's armies also besieged the city of Leiden. They broke off their siege when nearby dykes were breached by the Dutch. William was content with the victory, and established the University of Leiden, the first university in the Northern Provinces.

William married for the third time on 24 April 1575 to Charlotte de Bourbon-Montpensier, a former French nun, who was also popular with the public, although less so with the Catholic faction.[23] They had six daughters. The marriage, which seems to have been a love match on both sides, was happy.

After failed peace negotiations in Breda in 1575, the war continued. The situation improved for the rebels when Don Requesens died unexpectedly in March 1576, and a large group of Spanish soldiers, not having received their salary in months, mutinied in November of that year and unleashed the "Spanish Fury" on Antwerp, sacking the city in what became a tremendous propaganda coup for the rebels. While the new governor, Don Juan of Austria, was en route, William of Orange got most of the provinces and cities to sign the Pacification of Ghent, in which they declared themselves ready to fight for the expulsion of Spanish troops together. However, he failed to achieve unity in matters of religion. Catholic cities and provinces would not allow freedom for Calvinists.

When Don Juan signed the Perpetual Edict in February 1577, promising to comply with the conditions of the Pacification of Ghent, it seemed that the war had been decided in favour of the rebels. However, after Don Juan took the city of Namur in 1577, the uprising spread throughout the entire Netherlands. Don Juan attempted to negotiate peace, but the prince intentionally let the negotiations fail. On 24 September 1577, he made his triumphal entry into Brussels, the capital. At the same time, Calvinist rebels grew more radical, and attempted to forbid Catholicism in areas under their control. William was opposed to this both for personal and political reasons. He desired freedom of religion, and he also needed the support of the less radical Protestants and Catholics to reach his political goals. On 6 January 1579, several southern provinces, unhappy with William's radical following, signed the Treaty of Arras, in which they agreed to accept their Catholic governor, Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma (who had succeeded Don Juan).

Five northern provinces, later followed by most cities in Brabant and Flanders, then signed the Union of Utrecht on 23 January, confirming their unity. William was initially opposed to the Union, as he still hoped to unite all provinces. Nevertheless, he formally gave his support on 3 May. The Union of Utrecht would later become a de facto constitution, and would remain the only formal connection between the Dutch provinces until 1797.

Declaration of Independence[edit]

In spite of the renewed union, the Duke of Parma was successful in reconquering most of the southern part of the Netherlands. Because he had agreed to remove the Spanish troops from the provinces under the Treaty of Arras, and because Philip II needed them elsewhere subsequently, the Duke of Parma was unable to advance any further until the end of 1581.

In March 1580 Philip issued a royal ban of outlawry against the Prince of Orange, promising a reward of 25,000 crowns to any man who would succeed in killing him. William responded with his Apology, a document (in fact written by Villiers) in which his course of actions was defended, the person of the Spanish king viciously attacked,[24] and his own Protestant allegiance restated.

In the meantime, William and his supporters were looking for foreign support. The prince had already sought French assistance on several occasions, and this time he managed to gain the support of Francis, Duke of Anjou, brother of King Henry III of France. On 29 September 1580, the Staten Generaal (with the exception of Zeeland and Holland) signed the Treaty of Plessis-les-Tours with the Duke of Anjou. The Duke would gain the title "Protector of the Liberty of the Netherlands" and become the new sovereign. This, however, required that the Staten Generaal and William renounce their formal support of the King of Spain, which they had maintained officially up to that moment.

On 22 July 1581, the Staten Generaal declared that they no longer recognised Philip II of Spain as their ruler, in the Act of Abjuration. This formal declaration of independence enabled the Duke of Anjou to come to the aid of the resisters. He did not arrive until 10 February 1582, when he was officially welcomed by William in Flushing. On 18 March, the Spaniard Juan de Jáuregui attempted to assassinate William in Antwerp. Although William suffered severe injuries, he survived thanks to the care of his wife Charlotte and his sister Mary. While William slowly recovered, Charlotte became exhausted from providing intensive care and died on 5 May. The Duke of Anjou was not very popular with the population. The provinces of Zeeland and Holland refused to recognise him as their sovereign, and William was widely criticised for what was called his "French politics". When Anjou's French troops arrived in late 1582, William's plan seemed to pay off, as even the Duke of Parma feared that the Dutch would now gain the upper hand.

However, Anjou himself was displeased with his limited powers and secretly decided to seize Antwerp by force. The citizens, who had been warned in time, ambushed Anjou and his troops as they entered the city on 18 January 1583, in what is known as the "French Fury". Almost all of Anjou's men were killed, and he was reprimanded by both Catherine de Medici and Elizabeth I of England (whom he had courted). Anjou's position became untenable, and he subsequently left the country in June. His departure discredited William, who nevertheless maintained his support for Anjou. William stood virtually alone on this issue and became politically isolated. Holland and Zeeland nevertheless maintained him as their stadtholder and attempted to declare him count of Holland and Zeeland, thus making him the official sovereign. In the middle of all this, William married for the fourth and final time on 12 April 1583 to Louise de Coligny, a widowed French Huguenot and daughter of Gaspard de Coligny. She was to be the mother of Frederick Henry (1584–1647), William's fourth legitimate son. With her, "Father William", as he was affectionately styled, settled at the Prinsenhof at Delft, and lived like a simple Dutch burgher.[25]

Assassination[edit]

The Burgundian Catholic Balthasar Gérard (born 1557) was a subject and supporter of Philip II, and regarded William of Orange as a traitor to the king and to the Catholic religion. In 1581, when Gérard learned that Philip II had declared William an outlaw and promised a reward of 25,000 crowns for his assassination, he decided to travel to the Netherlands to kill William. He served in the army of the governor of Luxembourg, Peter Ernst I von Mansfeld-Vorderort, for two years, hoping to get close to William when the armies met. This never happened, and Gérard left the army in 1584. He went to the Duke of Parma to present his plans, but the Duke was unimpressed. In May 1584, he presented himself to William as a French nobleman, and gave him the seal of the Count of Mansfelt. This seal would allow forgeries of the messages of Mansfelt to be made. William sent Gérard back to France to pass the seal on to his French allies.

Gérard returned in July, having bought two wheel-lock pistols on his return journey. On 10 July, he made an appointment with William of Orange in his home in Delft, the Prinsenhof. That day, William was having dinner with his guest Rombertus van Uylenburgh. After William left the dining room and walked downstairs, van Uylenburgh heard Gérard shoot William in the chest at close range. Gérard fled immediately.

According to official records,[26] William's last words were:[27]

Mon Dieu, ayez pitié de mon âme; mon Dieu, ayez pitié de ce pauvre peuple. (My God, have pity on my soul; my God, have pity on this poor people).

Gérard was caught before he could escape Delft, and was imprisoned. He was tortured before his trial on 13 July, where he was sentenced to an execution brutal even by the standards of that time. The magistrates decreed that the right hand of Gérard should be burned off with a red-hot iron, that his flesh should be torn from his bones with pincers in six different places, that he should be quartered and disembowelled alive, that his heart should be torn from his chest and flung in his face, and that, finally, his head should be cut off.[28]

William was the first politician to be assassinated by handgun. (The Scottish Regent Moray had been shot 13 years earlier in the first firearm assassination of a head of government.)[29]

Burial and tomb[edit]

Traditionally, members of the Nassau family were buried in Breda, but as that city was under royal control when William died, he was buried in the New Church in Delft. The monument on his tomb was originally very modest, but it was replaced in 1623 by a new one, made by Hendrik de Keyser and his son Pieter.

Since then, most of the members of the House of Orange-Nassau, including all Dutch monarchs, have been buried in the same church. His great-grandson William III and II, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, and Stadtholder in the Netherlands, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Legacy[edit]

Succession and family ties[edit]

Philip William, William's eldest son by his first marriage, to Anna of Egmond, succeeded him as the Prince of Orange. However, as Philip William was a hostage in Spain and had been for most of his life, his brother Maurice of Nassau was appointed Stadholder and Captain-General at the suggestion of Johan van Oldenbarneveldt, and as a counterpoise to the Earl of Leicester. Phillip William died in Brussels on 20 February 1618 and was succeeded by his half-brother Maurice, the eldest son by William's second marriage, to Anna of Saxony, who became Prince of Orange. A strong military leader, he won several victories over the Spanish. Van Oldenbarneveldt managed to sign a very favourable twelve-year armistice in 1609, although Maurice was unhappy with this. Maurice was a heavy drinker and died on 23 April 1625 from liver disease. Maurice had several sons by Margaretha van Mechelen, but he never married her. So, Frederick Henry, Maurice's half-brother (and William's youngest son from his fourth marriage, to Louise de Coligny) inherited the title of Prince of Orange. Frederick Henry continued the battle against the Spanish. Frederick Henry died on 14 March 1647 and is buried with his father William "The Silent" in Nieuwe Kerk, Delft.[30] The Netherlands became formally independent after the Peace of Münster in 1648.

The son of Frederick Henry, William II of Orange succeeded his father as stadtholder, as did his son, William III of Orange. The latter also became king of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1689. Although he was married to Mary II, Queen of Scotland and England for 17 years, he died childless in 1702. He appointed his cousin Johan Willem Friso (William's great-great-great-grandson) as his successor. Because Albertine Agnes, a daughter of Frederick Henry, married William Frederik of Nassau-Dietz, the present royal house of the Netherlands is descended from William the Silent through the female line. See House of Orange for a more extensive overview. As the chief financer and political and military leader of the early years of the Dutch revolt, William is considered a national hero in the Netherlands, even though he was born in Germany, and usually spoke French.

In the 19th century the Netherlands became a constitutional monarchy, currently with King Willem-Alexander as head of state: he has cognatic descent from William of Orange. All stadtholders after William of Orange were drawn from his descendants or the descendants of his brother.

Many of the Dutch national symbols can be traced back to William of Orange:

- He is the ancestor of the Dutch monarchy

- The flag of the Netherlands (red, white and blue) is derived from the flag of the prince, which was orange, white and blue.

- The coat of arms of the Netherlands is based on that of William of Orange. Its motto Je maintiendrai (French, "I will maintain") was also used by William, who based it on the motto of his cousin René of Châlon, who used Je maintiendrai Châlon.

- The national anthem of the Netherlands, the Wilhelmus, was originally a propaganda song for William. It was probably written by Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, a supporter of him.

- The national colour of the Netherlands is orange, and it is used, among other things, in the clothing of Dutch athletes.

- The Prussian Order of the Black Eagle, founded by Frederick I of Prussia in 1702, had an orange sash in honour of his mother, Louise Henriette of Nassau, who was the granddaughter of William the Silent.

Other remembrances of William of Orange:

- A statue of William the Silent was erected in 1928 on the main campus of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, a legacy of the university's founding by ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church in 1766. The statue is commonly known to students and alumni as "Willie the Silent" and contains an inscription referring to William as "Father of his Fatherland".[31][32]

- Another statue of William the Silent was erected in 1908 in front of the Marktkirche, Wiesbaden, Germany. The statue is a copy of the original statue by Walter Schott in front of the Berlin Palace, which was destroyed in the World War II.

- In January 2008, the asteroid 12151 Oranje-Nassau was named after him.[33]

Epithet[edit]

There are several explanations for the origin of the style, "William the Silent". The most common one relates to his prudence in regard to a conversation with Henry II, the king of France.

One day, during a stag-hunt in the Bois de Vincennes, Henry, finding himself alone with the Prince, began to speak of the great number of Protestant sectaries who, during the late war, had increased so much in his kingdom to his great sorrow. His conscience, said the King, would not be easy nor his realm secure until he could see it purged of the "accursed vermin," who would one day overthrow his government, under the cover of religion, if they were allowed to get the upper hand. This was the more to be feared since some of the chief men in the kingdom, and even some princes of the blood, were on their side. But he hoped by the grace of God and the good understanding that he had with his new son, the King of Spain, that he would soon get the better of them. The King talked on thus to Orange in the full conviction that he was aware of the secret agreement recently made with the Duke of Alba for the extirpation of heresy. But the Prince, subtle and adroit as he was, answered the good King in such a way as to leave him still under the impression that he, the Prince, knew all about the scheme proposed by Alba; and on this understanding the King revealed all the details of the plan which had been arranged between the King of Spain and himself for the rooting out and rigorous punishment of the heretics, from the lowest to the highest rank, and in this service the Spanish troops were to be mainly employed.[34]

Exactly when and by whom the nickname "the Silent" was used for the first time is not known with certainty. It is traditionally ascribed to Cardinal de Granvelle, who is said to have referred to William as "the silent one" sometime during the troubles of 1567. Both the nickname and the accompanying anecdote are first found in a historical source from the early 17th century.[35][36]

In the Netherlands, William is known as the Vader des Vaderlands, "Father of the Fatherland", and the Dutch national anthem, the Wilhelmus,[37] was written in his honour.

Popular culture[edit]

This proverb is often attributed to William,[38] but it has not been found in his written texts,[39] and it is also attributed to William II, William III[39] and Charles the Bold.[40]One need not hope to undertake, nor succeed to persevere.

- He is featured as a playable leader in the computer strategy game series Civilization, appearing in Civilization III: Conquests, Civilization IV: Beyond the Sword, and Civilization V: Gods & Kings.

- A Dutch YouTube channel called Studio Massa has a series of videos featuring him as a rapper who goes by the artistic name of Stille Willem (Silent William). The most famous of such videos are Fijn Uitgedoste Barbaar (Finely Clothed Barbarian) and Specerijen (Spices).

Personal life[edit]

First marriage[edit]

In the castle of Buren on 6 July 1551, the 18-year-old William married Anna van Egmond en Buren, aged 18 and the wealthy heiress to the lands of her father. William thus gained the titles Lord of Egmond and Count of Buren. The couple had a happy marriage and became the parents of three children together; their son Philip William would succeed William as prince. Anna died on 24 March 1558, leaving William much grieved.

A couple of years after Anna's death, William had a brief relationship with Eva Elincx, a commoner, leading to the birth of an illegitimate son, Justinus van Nassau:[41][42] William officially recognised Justinus as his son and took responsibility for his education – Justinus would become an admiral in adult life.

Second marriage[edit]

On 25 August 1561, William of Orange married for the second time. His new wife, Anna of Saxony, was tumultuous, and it is generally assumed that William married her to gain more influence in Saxony, Hesse and the Palatinate.[13] The couple had two sons and three daughters. One of the sons died in infancy and the other son, the famous Maurice of Nassau, who was to eventually succeed his father as stadtholder, never married. Anna died after William renounced her and her own family imprisoned her in one of their castles. The cause was due to the accusation that she committed adultery with the lawyer Jan Rubens, and became pregnant by him, giving birth to a daughter. Before her death William had already announced his third marriage, which drew the disapproval of her family who argued that, despite the adultery, the two were still married.

Third marriage[edit]

William married for the third time on 12 June 1575 to Charlotte de Bourbon-Montpensier, a former French nun, who was also popular with the public. They had six daughters. The marriage, which seems to have been a love match on both sides, was happy. Charlotte allegedly died from exhaustion while trying to nurse her husband after an assassination attempt in 1582.[43] Though William was outwardly stoical, it was feared that his grief might cause a fatal relapse. Charlotte's death was widely mourned.

Fourth marriage[edit]

William married for the fourth and final time on 12 April 1583 to Louise de Coligny, a French Huguenot and daughter of Gaspard de Coligny. She was to be the mother of Frederick Henry (1584–1647), William's fourth legitimate son and fifteenth legitimate child. This youngest of William's children, who was born only a few months before William's death, was to be the only one of his sons to bear children and carry the dynasty forward. Incidentally, Frederick Henry's only male-line grandson, William III, would become king of England, Scotland and Ireland, but he would die childless, at which point the lineage of William the Silent would end, to be succeeded by that of his brother John VI.

Issue[edit]

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Anna of Egmond (married 6 July 1551; b. est. 1534, d. 24 March 1558) | |||

| Countess Maria of Nassau | 22 November 1553 | c. 23 July 1555 | Died in infancy. |

| Philip William, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

19 December 1554 | 20 February 1618 | Married Eleonora of Bourbon-Condé. No issue. |

| Countess Maria of Nassau | 7 February 1556 | 10 October 1616 | married Count Philip of Hohenlohe-Neuenstein |

| By Anna of Saxony (married 25 August 1561, annulled 22 March 1571; b. 23 December 1544, d. 18 December 1577) | |||

| Countess Anna of Nassau | 31 October 1562 | Died at birth. | |

| Countess Anna of Nassau | 5 November 1563 | 13 June 1588 | Married Count Wilhelm Ludwig von Nassau-Dillenburg |

| Count Maurice August Phillip of Nassau | 8 December 1564 | 3 March 1566 | Died in infancy. |

| Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

13 November 1567 | 23 April 1625 | Never married. |

| Countess Emilia of Nassau | 10 April 1569 | 6 March 1629 | Married Manuel de Portugal (son of pretender to the Portuguese throne António, Prior of Crato), 10 children. |

| By Charlotte of Bourbon (married 24 June 1575; b. c. 1546, d. 5 May 1582) | |||

| Countess Louise Juliana of Nassau | 31 March 1576 | 15 March 1644 | Married Frederick IV, Elector Palatine, 8 children. Her son, Frederick V, Elector Palatine would be the grandfather of George I of Great Britain. |

| Countess Elisabeth of Nassau | 26 April 1577 | 3 September 1642 | Married to Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, and had issue, including Frédéric Maurice, duc de Bouillon and Henri de la Tour d'Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne. |

| Countess Catharina Belgica of Nassau | 31 July 1578 | 12 April 1648 | Married to Count Philip Louis II of Hanau-Münzenberg. |

| Countess Charlotte Flandrina of Nassau | 18 August 1579 | 16 April 1640 | A nun. After her mother's death in 1582 her French grandfather asked for Charlotte Flandrina to stay with him. She converted to Roman Catholicism and entered a convent in 1593. |

| Countess Charlotte Brabantina of Nassau | 17 September 1580 | August 1631 | Married Claude, Duc de Thouars, and had issue including Charlotte de la Trémoille wife of James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby. |

| Countess Emilia Antwerpiana of Nassau | 9 December 1581 | 28 September 1657 | Married Frederick Casimir, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken-Landsberg. |

| By Louise de Coligny (married 24 April 1583; b. 23 September 1555, d. 13 November 1620) | |||

| Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and Count of Nassau |

29 January 1584 | 14 March 1647 | Married to Countess Amalia of Solms-Braunfels, father of William II and grandfather of William III, King of England, Scotland, Ireland and Stadtholder of the Netherlands. |

Between his first and second marriages, William had a common law relationship with Eva Elincx. They had a son, Justinus van Nassau (1559–1631), whom William acknowledged. On 4 December 1597 Justinus van Nassau married Anne, Baronesse de Mérode (9 January 1567 – Leiden, 8 October 1634). They had three children.

Coats of arms and titles[edit]

A noble's power was generally based on his ownership of vast tracts of land and lucrative offices. Besides being ruler over the principality of Orange and a Knight of the Golden Fleece, William possessed other estates, mostly enfeoffed to some other sovereign, either the King of France or the imperial Habsburgs. As holder of these fiefs, he was inter alia:

- Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen

- Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, Katzenelnbogen, and Vianden

- Viscount of Antwerp

- Baron of Breda, Lands of Cuijk, City of Grave, Diest, Herstal, Warneton, Beilstein, Arlay, and Nozeroy; Lord of Dasburg, Geertruidenberg, Hooge en Lage Zwaluwe, Klundert, Montfort, Naaldwijk, Niervaart, Polanen, Steenbergen, Willemstad, Bütgenbach, Sankt Vith, and Besançon

William used two sets of arms in his lifetime. The first one shown below was his ancestral arms of Nassau. The second arms he used most of his life from the time he became Prince of Orange on the death of his cousin René of Châlon. He placed the arms of Châlon-Arlay as princes of Orange as an inescutcheon on his father's arms. In 1582, William purchased the marquisate of Veere and Vlissingen in Zeeland. It had been the property of Philip II since 1567, but had fallen into arrears to the province. In 1580, the Court of Holland ordered it sold. William bought it as it gave him two more votes in the States of Zeeland. He owned the government of the two towns, and so could appoint their magistrates. He already had one as First Noble for Philip William, who had inherited Maartensdijk. This made William the predominant member of the States of Zeeland. It was a smaller version of the countship of Zeeland (and Holland) promised to William, and was a potent political base for his descendants. William then added the shield of Veere and Buren to his arms as shown in the third coat of arms below. It shows how arms were used to represent political power in general, and the growing political power of William.[44]

Ancestry[edit]

| Ancestors of William the Silent |

|---|

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Abelous, Louis David (1872). William the Taciturn. Translated by Lacroix, J. P. The Library of Congress catalogued with subject "William I, Prince of Orange (1534–1584). New York: Nelson & Phillips; [etc.]

- ^ John Whitehead Historian, Oxford, Oriel College, weblog page about William I Once I was a clever boy

- ^ "Willem van Oranje". Canon van Nederland (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Hoe wordt Willem van Oranje vader des vaderlands?". NPO Kennis (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edmundson 1911, p. 672.

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 29.

- ^ As of 1549, the Low Countries, also known as the "Seventeen Provinces" comprised the present-day Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of northern France and Western Germany.

- ^ J. Thorold Rogers, The Story of Nations: Holland. London, 1889; Romein, J., and Romein-Verschoor, A. Erflaters van onze beschaving. Amsterdam 1938–1940, p. 150. (Dutch, at DBNL.org).

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 34.

- ^ Motley, John Lothrop (1885). The Rise of the Dutch Republic. Vol. I. Harper Brothers.

As Philip was proceeding on board the ship which was to bear him forever from the Netherlands, his eyes lighted upon the Prince. His displeasure could no longer be restrained. With angry face he turned upon him, and bitterly reproached him for having thwarted all his plans by means of his secret intrigues. William replied with humility that every thing which had taken place had been done through the regular and natural movements of the states. Upon this the King, boiling with rage, seized the Prince by the wrist, and shaking it violently, exclaimed in Spanish, "No los estados, ma vos, vos, vos!—Not the estates, but you, you, you!" repeating thrice the word vos, which is as disrespectful and uncourteous in Spanish as "toi" in French.

- ^ See William of Orange, Apologie contre l'édit de proscription publié en 1580 par Philippe II, Roi d'Espagne, ed. A. Lacroix (Brussels, 1858), pp. 87–89 (French version); Apologie, ofte Verantwoordinghe, ed. C. A. Mees (Antwerpen, 1923), pp. 48–50 (Dutch version); Pontus Payen, Mémoires, I, ed. A. Henne (Brussels, 1860), pp. 6–9.

- ^ Lacroix (1858), p. 89; Mees (1923), p. 50.

- ^ a b Wedgwood (1944) pp. 49–50.

- ^ Herman Kaptein, De Beeldenstorm (2002), p. 22.

- ^ "Et quamquam ipse Catholicae Religioni adhaerere constituerit, non posse tamen ei placere, velle Principes animis hominum imperare, libertatemque Fidei & Religionis ipsis adimere." C. P. Hoynck van Papendrecht, Vita Viglii ab Aytta, in Analecta belgica I, 41–42 (F. Postma, "Prefigurations of the future? The views on the boundaries of Church and State of William of Orange and Viglius van Aytta (1565–1566)", in A. A. McDonald and A. H. Huussen (eds.), Scholarly environments: centres of learning and institutional contexts, 1560–1960 (2004), 15–32, esp. 15).

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 104.

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 105.

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 108.

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 109.

- ^ Midelfort, H. C. Erik (1994). Mad Princes of Renaissance Germany. Virginia, United States: University of Virginia Press (published 22 January 1996). p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8139-1501-2.

- ^ Wedgwood (1944) p. 120.

- ^ Parker, G., The Dutch Revolt (revised edition, 1985), p. 148.

- ^ Edmundson 1911, p. 673.

- ^ H. R. Rowen, The Princes of Orange: The Stadholders in the Dutch Republic (Cambridge, 1990), p. 25; M. van Gelderen, The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555–1590 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 151.

- ^ Edmundson 1911, p. 674.

- ^ Minutes of the States-General of 10 July 1584, quoted in J. W. Berkelbach van der Sprenkel, De Vader des Vaderlands, Haarlem 1941, p. 29: "Ten desen daghe es geschiet de clachelycke moort van Zijne Excellentie, die tusschen den een ende twee uren na den noen es ghescoten met een pistolet gheladen met dry ballen, deur een genaempt Baltazar Geraert ... Ende heeft Zijne Excellentie in het vallen gheroepen: Mijn God, ontfermpt U mijnder ende Uwer ermen ghemeynte (Mon Dieu ayez pitié de mon âme, mon Dieu, ayez pitié de ce pauvre peuple)."

- ^ Although commonly accepted, his last words might have been modified for propaganda purposes. See Charles Vergeer, "De laatste woorden van prins Willem", Maatstaf 28 (1981), no. 12, pp. 67–100. The debate has some history, with critics pointing to sources saying that William died immediately after having been shot and proponents stating that there would have been little opportunity to fabricate the words between the time of the assassination and the announcement of the murder to the States-General. Of the final words themselves, several slightly different versions are in circulation, the main differences being of style.

- ^ Motley, John L. (1856). The Rise of the Dutch Republic, Vol. 3.

- ^ Harvey, A. D. (1 June 1991). "The pistol as assassination weapon: A case of technological lag". Terrorism and Political Violence. 3 (2): 92–98. doi:10.1080/09546559108427107. ISSN 0954-6553.

- ^ Nieuwekerk-Delft, NL.

- ^ "Willie". Libraries: Special Collections and University Archives. Rutgers University. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Father of His Fatherland, Founder of the United States of the Netherlands". Flickr. Yahoo!. 9 May 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Planetoïde (12151) Oranje-Nassau". NL: Xs4all. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ William the Silent by Frederic Harrison pp. 22–23

- ^ "den swijger", "den Schweiger": Emanuel van Meteren, 1608 and 1614; cf. "Taciturnus": Famiano Strada, 1635. The Dutch historian Robert Fruin (1864) has argued that this is in fact an erroneous rendering of the phrase "astutus Gulielmus", "cunning William", found in a Latin source of 1574 and attributed there to the Flemish inquisitor Pieter Titelmans. See Leiden University, De Tachtigjarige Oorlog. Willem de Zwijger.

- ^ Fruin, Robert (1903). "Verspreide geschriften. Deel 8. Kritische studiën over geschiedbronnen. Deel 2. Historische schetsen en boekbeoordeelingen. Deel 1. 'Willem de Zwijger (1864)'". DBNL Digitale bibiotheek voor de Nederlandse letteren (in Dutch). pp. 404–407. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ The song is named after the first word of the first line, Wilhelmus, a Latinised form of the prince's first name.

- ^ For example: Wilson, Edmund (1963). O Canada: An American's Notes on Canadian Culture. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374505160.

- ^ a b Schaper, Bertus Willem (1954–1955). "Het werkende woord. Het Adagium van Willem de Zwijger" [The working word. The Adage of William the Silent]. Maatstaf: Maandblad voor letteren (in Dutch). 2: 24–31. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ For example: van der Merwe, Pieter Ben (2004). Mobile Commerce Over GSM: A Banking Perspective on Security (PDF). University of Pretoria. p. vii.

- ^ "Justinus of Nassau is the son, probably born in September 1559, of the Prince and Eva Elinx, who, according to some, was the daughter of a mayor of Emmerich." (Adriaen Valerius, Nederlandtsche gedenck-clanck. P.J. Meertens, N.B. Tenhaeff and A. Komter-Kuipers (eds.). Wereldbibliotheek, Amsterdam 1942; p. 148, note. (Dutch, on DBNL)).

- ^ "...our son Justin van Nassau" in letter from William of Orange to Diederik Sonoy dated 16 July 1582, facsimile at Inghist.nl

- ^ Wedgwood, C.V. (1944). William the Silent. Jonathan Cape. pp. 235.

- ^ Rowen, Herbert H. (1988). The princes of Orange: the stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780521345255.

References[edit]

- Petrus Johannes Blok, History of the People of the Netherlands. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1898.

- Herbert H. Rowen, The Princes of Orange: The Stadholders in the Dutch Republic. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Edmundson, George (1911). "William of Orange". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 672–674.

- Jardine, Lisa. The Awful End of William the Silent: The First Assassination of a Head of State with A Handgun. London: HarperCollins: 2005: ISBN 0-00-719257-6

- John Lothrop Motley. The Rise of the Dutch Republic. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1855.

- John Lothrop Motley. History of the United Netherlands from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort. London: John Murray, 1860.

- John Lothrop Motley. The Life and Death of John of Barneveld: Advocate of Holland. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1874.

- van der Lem, Anton. 1995. De Opstand in de Nederlanden 1555–1609. Utrecht: Kosmos. ISBN 90-215-2574-7.

- Various authors. 1977. Winkler Prins – Geschiedenis der Nederlanden. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 90-10-01745-1.

- Wedgwood, Cicely Veronica. William the Silent: William of Nassau, Prince of Orange, 1533–1584. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1944.

Further reading[edit]

- Shorto, Russell (2013). Amsterdam: A History of the World's Most Liberal City. New York: Doubleday.

External links[edit]

- The Revolt of the Netherlands

- Het Huis van Oranje-Nassau en de Nederlandse geschiedenis (in Dutch)

- Willem van Oranje[permanent dead link]. Dutch history website (in Dutch)

- The Complete Correspondence of William I of Orange. Digital archive by the Huygens Institute for Dutch History (in Dutch)

- William the Silent

- 1533 births

- 1584 deaths

- People from Dillenburg

- Assassinated Dutch politicians

- Burials in the Royal Crypt at Nieuwe Kerk, Delft

- Counts in Germany

- Deaths by firearm in the Netherlands

- Dutch Protestants

- Dutch rebels

- Stadtholders in the Low Countries

- German people of the Eighty Years' War

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Leiden University

- Lords of Breda

- Child monarchs

- People murdered in the Netherlands

- People of the French Wars of Religion

- Princes of Orange

- House of Nassau

- House of Orange-Nassau

- 16th-century rebels

- Politicians assassinated in the 16th century

- 16th-century governors

- Stadtholders of Frisia