Vicia

| Vicia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vicia orobus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Faboideae |

| Clade: | Inverted repeat-lacking clade |

| Tribe: | Fabeae |

| Genus: | Vicia L. (1753) |

| Type species | |

| Faba sativa | |

| Species[1] | |

|

247; see text | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Vicia is a genus of over 240 species of flowering plants that are part of the legume family (Fabaceae), and which are commonly known as vetches. Member species are native to Europe, North America, South America, Asia and Africa. Some other genera of their subfamily Faboideae also have names containing "vetch", for example the vetchlings (Lathyrus) or the milk-vetches (Astragalus). The lentils are included in genus Vicia, and were formerly classified in genus Lens.[3] The broad bean (Vicia faba) is sometimes separated in a monotypic genus Faba; although not often used today, it is of historical importance in plant taxonomy as the namesake of the order Fabales, the Fabaceae and the Faboideae. The tribe Vicieae in which the vetches are placed is named after the genus' current name. The true peas (Pisum) are among the closest living relatives of vetches.

Use by humans[edit]

| |||||

| "Grains of puyr" in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bitter vetch (V. ervilia) was one of the first domesticated crops. It was grown in the Near East about 9,500 years ago, starting perhaps even one or two millennia earlier during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A. By the time of the Central European Linear Pottery culture – about 7,000 years ago – broad bean (V. faba) had also been domesticated. Vetch has been found at Neolithic and Eneolithic sites in Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia.[4] And at the same time, at the opposite end of Eurasia, the Hoabinhian people also utilized the broad bean in their path towards agriculture, as shown by the seeds found in Spirit Cave, Thailand.[5]

Bernard of Clairvaux shared a bread-of-vetch meal with his monks during the famine of 1124 to 1126, as an emblem of humility.[Note 1] However, the bitter vetch largely was dropped from human use over time. It was only used to save as a crop of last resort in times of starvation: vetches "featured in the frugal diet of the poor until the eighteenth century, and even reappeared on the black market in the South of France during the Second World War", Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, of Marseillais background, has remarked.[7] However, broad beans remained prominent. In the Near East the seeds are mentioned in Hittite and Ancient Egyptian sources dating from more than 3,000 years ago as well as in the Christian Bible,[Note 2] and in the large Celtic Oppidum of Manching from the La Tène culture in Europe some 2,200 years ago. Dishes resembling ful medames are attested in the Jerusalem Talmud which was compiled before 400 AD.

In our time, the common vetch (V. sativa) has also risen to prominence. Together with broad bean cultivars such as horse bean or field bean, the FAO includes it among the 11 most important pulses in the world. The main usage of the common vetch is as forage for ruminant animals, both as fodder and legume, but there are other uses, as tufted vetch V. cracca is grown as a mid-summer pollen source for honeybees.

In 2017, global production of vetches was 920,537 tonnes.[8] That year, 560,077 acres were devoted to the cultivation of vetches in the world. Over 54% of that output came from Europe alone. Africa (17.8% of world total), Asia (15.6% of world total), Americas (10.6% of world total) and Oceania (1.8% of world total).[14]

The bitter vetch, too, is grown extensively for forage and fodder, as are hairy vetch (V. villosa, also called fodder vetch), bard vetch (V. articulata), French vetch (V. serratifolia) and Narbon bean (V. narbonensis). V. benghalensis and Hungarian vetch (V. pannonica) are cultivated for forage and green manure.

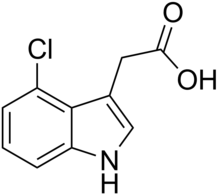

The vetches also have a broad variety of other purposes. The Hairy Vetch has well-established uses as a green manure and as an allelopathic cover crop. As regards the broad bean, it is known to accumulate aluminum in its tissue; in polluted soils it may be useful in phytoremediation, but with one per mil of aluminum in the dry plant (possibly more in the seeds), it might not be edible anymore. The robust plants are useful as a beetle bank to provide habitat and shelter for carnivorous beetles and other arthropods to keep down pest invertebrates. When the root nodules of broad bean are inoculated with the rhodospirillacean bacterium Azospirillum brasilense and the glomeracean fungus Glomus clarum, the species can also be productively grown in salty soils.[9][10][11] In the 1980s, the auxin 4-Cl-IAA was studied in V. amurensis and the broad bean,[12][13] and since 1990, the antibacterial γ-thionins fabatin-1 and -2 have been isolated from the latter species.

Despite a small chromosome count of n=6, the broad bean has a high DNA content, making it easy for a micronucleus test of its root tips to recognize genotoxic compounds. A lectin from V. graminea is used to test for the medically significant N blood group.

Toxicity[edit]

The vetches grown as forage are generally toxic to non-ruminants (such as humans), at least if eaten in quantity. Cattle and horses have been poisoned by V. villosa and V. benghalensis, two species that contain canavanine in their seeds. Canavanine, a toxic analogue of the amino acid arginine, has been identified in Hairy Vetch as an appetite suppressant for monogastric animals, while Narbon bean contains the quicker-acting but weaker γ-glutamyl-S-ethenylcysteine.[14] In common vetch, γ-glutamyl-β-cyanoalanine has been found. The active part of this molecule is β-cyanoalanine. It inhibits the conversion of the sulfur amino acid methionine to cysteine.

Cystathionine, an intermediary product of this biochemical pathway, is secreted in urine.[15] This process can effectively lead to the depletion of vital protective reserves of the sulfur amino acid cysteine and thereby making Vicia sativa seed a dangerous component in mixture with other toxin sources. The Spanish pulse mix comuña contains common vetch and bitter vetch in addition to vetchling (Lathyrus cicera) seeds; it can be fed in small quantities to ruminants, but its use as a staple food will cause lathyrism even in these animals. Moreover, common vetch as well as broad bean – and probably other species of Vicia too – contain oxidants like convicine, isouramil, divicine and vicine in quantities sufficient to lower glutathione levels in G6PD-deficient persons to cause favism disease. At least broad beans also contain the lectin phytohemagglutinin and are somewhat poisonous if eaten raw. Split common vetch seeds resemble split red lentils (Lens culinaris), and has been occasionally mislabelled as such by exporters or importers to be sold for human consumption. In some countries where lentils are highly popular – e.g., Bangladesh, Egypt, India and Pakistan – import bans on suspect produce have been established to prevent these potentially harmful scams.[14][16]

Ecology[edit]

Vetches have cylindrical root nodules of the indeterminate type and are thus nitrogen-fixing plants. Their flowers usually have white to purple or blue hues, but may be red or yellow; they are pollinated by bumblebees, honey bees, solitary bees and other insects.

Vicia species are used as food plants by the caterpillars of some butterflies and moths, such as:

- Coleophora cracella – only found on Vicia species

- Coleophora fuscicornis – only found on smooth tare (V. tetrasperma)

- Paratalanta pandalis – recorded on bush vetch (V. sepium)

- Chionodes lugubrella – recorded on tufted vetch (V. cracca)

- Lime-speck pug (Eupithecia centaureata) – recorded on tufted vetch (V. cracca)

- Double-striped pug (Gymnoscelis rufifasciata) – recorded on broad bean (V. faba)

- Provençal short-tailed blue (Everes alcetas)

- Amanda's blue (Polyommatus amandus) – only found on Vicia species

- The flame (Axylia putris)

- Blackneck (Lygephila pastinum) – recorded on tufted vetch (V. cracca)

- Angle shades (Phlogophora meticulosa)

- Colias species, e.g., Clouded sulphur (C. philodice)

- Wood white (Leptidea sinapis)

- Pea moth (Cydia nigricana)

Most other parasites and plant pathogens affecting vetches have been recorded on the broad bean, the most widely cultivated and economically significant species. They include the mite Balaustium vignae whose adults are found on broad bean, the potexviruses Alternanthera mosaic virus, clover yellow mosaic virus and white clover mosaic virus, and several other virus species such as Bidens mosaic virus, tobacco streak virus, Vicia cryptic virus and Vicia faba endornavirus.

Selected species[edit]

- Vicia americana – American vetch, purple vetch, mat vetch

- Vicia amoena

- Vicia amurensis Oett. (=V. japonica sensu auct non A.Gray)

- Vicia andicola Kunth

- Vicia articulata Hornem. – bard vetch

- Vicia bakeri Ali (=V. sylvatica Benth.)

- Vicia basaltica Plitmann

- Vicia benghalensis L.

- Vicia biennis L.

- Vicia bithynica (L.) L. – Bithynian vetch

- Vicia bungei Ohwi

- Vicia canescens Labill.

- Vicia cappadocica Boiss. & Balansa

- Vicia caroliniana Walter – Carolina wood vetch

- Vicia cassubica L. – Kashubian vetch[17]

- Vicia cracca – tufted vetch

- Vicia cuspidata Boiss.

- Vicia cusnae

- Vicia cypria Unger & Kotschy

- Vicia disperma DC. (=V. parviflora Loisel.)

- Vicia dumetorum L.

- Vicia ervilia – bitter vetch

- Vicia esdraelonensis Warb. & Eig

- Vicia faba – fava bean, broad bean, faba bean, horse bean, field bean, bell bean, tic bean

- Vicia galeata Boiss.

- Vicia galilaea Plitmann & Zohary

- Vicia gigantea Bunge

- Vicia graminea Sm.

- Vicia grandiflora Scop. (=V. kitaibeliana)

- Vicia hassei S.Watson

- Vicia hirsuta – hairy tare

- Vicia hololasia Woronow

- Vicia hulensis Plitmann

- Vicia hybrida L.

- Vicia japonica A.Gray

- Vicia lathyroides – spring vetch

- Vicia lens – lentil

- Vicia lilacina Ledeb.

- Vicia linearifolia Hook. & Arn. (=V. parviflora Hook. & Arn.)

- Vicia loiseleurii (M.Bieb.) Litv. (=V. pubescens sensu auct. fl. Cauc.)

- Vicia lutea – yellow vetch

- Vicia menziesii Spreng. – Hawaiian vetch

- Vicia minutiflora F.G. Dietr. – pygmyflower vetch

- Vicia monantha Retz. – single-flowered vetch

- Vicia nana Vogel

- Vicia narbonensis L. – Narbon bean, moor's pea (=V. serratifolia sensu auct. non Jacq.)

- Vicia nigricans – black vetch

- Vicia nigricans ssp. gigantea (=V. gigantea Hook.) – giant vetch

- Vicia onobrychioides L.

- Vicia oroboides Wulfen

- Vicia orobus DC. – upright vetch, wood bitter-vetch

- Vicia palaestina Boiss.

- Vicia pannonica – Hungarian vetch

- Vicia parviflora Cav. – slender vetch, slender tare (=V. tenuissima)

- Vicia peregrina L.

- Vicia pisiformis L. – pea-flowered vetch

- Vicia pseudo-orobus Fisch. & C. A. Mey.

- Vicia pubescens (DC.) Link

- Vicia pyrenaica

- Vicia sativa – common vetch, narrow-leaved vetch, tare

- Vicia sepium – bush vetch

- Vicia sericocarpa Fenzl

- Vicia serratifolia Jacq. – French vetch (formerly in V. narbonensis)

- Vicia sylvatica L. – wood vetch

- Vicia tenuifolia Roth. – fine-leaved vetch

- Vicia tenuifolia ssp. dalmatica (A.Kern.) Greuter (=V. dalmatica, V. tenuifolia sensu auct. non Roth.)

- Vicia tetrasperma – smooth tare, smooth vetch

- Vicia tsydenii Malyschev

- Vicia unijuga A.Br.

- Vicia villosa – hairy vetch, fodder vetch, winter vetch

Plants formerly placed in Vicia include:

- Lens nigricans (as V. nigricans (M.Bieb.) Janka)

Etymology[edit]

Vicia means 'binder' in Latin; this was the name used by Pliny for vetch.[18]

The vetch is also referenced by Horace in his account of 'The town mouse and country mouse' as ervum.[19] This is said to be a source of comfort for the country mouse after a disturbing insight into urban life.

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Their bread like the prophets of old, was made of barley, millet and vetch and was of such miserable quality that once a visiting monk, lamenting sadly their plight, took away with him some of what had been set before him in the guest-house, that he might show to everybody the marvel of men, and such men, living on the like." (Vita Prima I.v.25, quoted in Williams (1952), p. 24).[6]

- ^ Usually translated simply as "beans"; the green beans (Phaseolus) are native to the Americas and were unknown in Europe before about 1500 AD.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Vicia L. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ a b Woodgate K, Maxted N, Bennett SJ (1999). "A generic conspectus of the forage legumes of the Mediterranean basin". In Bennett S, Cocks PS (eds.). Genetic Resources of Mediterranean Pasture and Forage Legumes. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture. Vol. 33 (1st ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 182–226. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4776-7. ISBN 978-94-010-6007-3. S2CID 29588535.

- ^ Lens Mill. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Daniel Zohary; Maria Hopf & Ehud Weiss (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954906-1.

- ^ Chester F. Gorman (1969). "Hoabinhian: a pebble tool complex with early plant associations in Southeast Asia". Science. 163 (3868): 671–673. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..671G. doi:10.1126/science.163.3868.671. PMID 17742735. S2CID 34052655.

- ^ Watkin Wynn Williams (1952). Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Manchester University Press.

- ^ Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat & Anthea Bell (2008). The History of Food (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4051-8119-8.

- ^ Citation error. See inline comment how to fix. [verification needed]

- ^ L. Lehle & W. Tanner (1973). "The function of myo-inositol in the biosynthesis of raffinose – purification and characterization of galactinol: sucrose 6-galactosyltransferase from Vicia faba seeds". European Journal of Biochemistry. 38 (1): 103–110. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03039.x. PMID 4774118.

- ^ H. Matsuda & Y. Suzuki (1984). "γ-guanidinobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase of Vicia faba leaves" (PDF). Plant Physiology. 76 (3): 654–657. doi:10.1104/pp.76.3.654. PMC 1064350. PMID 16663901.

- ^ H. A. Ross & H. V. Davies (1992). "Purification and characterization of sucrose synthase from the cotyledons of Vicia fava L." (PDF). Plant Physiology. 100 (8): 1008–1013. doi:10.1104/pp.100.2.1008. PMC 1075657. PMID 16653008.

- ^ Tanja Pless; Michael Boettger; Peter Hedden & Jan Graebe (1984). "Occurrence of 4-Cl-indoleacetic acid in broad beans and correlation of its levels with seed development" (PDF). Plant Physiology. 74 (2): 320–323. doi:10.1104/pp.74.2.320. PMC 1066676. PMID 16663416.

- ^ Masato Katayama; Singanallore V. Thiruvikraman & Shingo Marumo (1987). "Identification of 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid and its methyl ester in immature seeds of Vicia amurensis (the tribe Vicieae), and their absence from three species of Phaseoleae" (PDF). Plant and Cell Physiology. 28 (2): 383–386.

- ^ a b D. Enneking (1994). The toxicity of Vicia species and their utilisation as grain legumes (PDF) (Ph.D. (Ag.Sc.) thesis). University of Adelaide.

- ^ Charlotte Ressler; Jeanne Nelson & Morris Pfeffer (1964). "A pyridoxal-β-cyanoalanine relation in the rat". Nature. 203 (4951): 1286–1287. Bibcode:1964Natur.203.1286R. doi:10.1038/2031286a0. PMID 14230211. S2CID 39261988.

- ^ "Vetch scandal". The Health Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. April 19, 1999. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ^ "Kashubian Vetch". Luontoportti. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ Gledhill, David (2008). "The Names of Plants". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521866453 (hardback), ISBN 9780521685535 (paperback). pp 401

- ^ Satires II.6, 117

- "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

External links and further reading[edit]

- G. Laghetti; A. R. Piergiovanni; I. Galasso; K. Hammer & P. Perrino (2000). "Single-flowered vetch (Vicia articulata Hornem.): a relic crop in Italy". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 47 (4): 461–465. doi:10.1023/A:1008711022396. S2CID 22502363.

- Vicia plant profiles, United States Department of Agriculture

- Mansfeld's database for cultivated plants (search for Vicia, 17 cultivated taxa listed)

- FAO's Neglected crops: 1492 from a different perspective Chapter 26: Grain legumes for animal feed

- R. Fitter & A. Collins (1974). The Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe.