Tyler Winklevoss

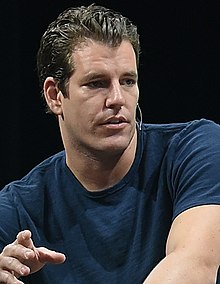

Winklevoss in 2015 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 21, 1981 Southampton, New York |

| Alma mater | Harvard University (BA) Christ Church, Oxford (MBA) |

| Height | 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) |

| Weight | 220 lb (100 kg) |

| Relative | Cameron Winklevoss |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Rowing |

| College team | Harvard College Oxford University |

| Team | United States Olympic Team |

| Achievements and titles | |

| Olympic finals | 6th place, Beijing Olympics |

Medal record | |

Tyler Howard Winklevoss (born August 21, 1981) is an American investor, founder of Winklevoss Capital Management and Gemini cryptocurrency exchange, and former Olympic rower. Winklevoss co-founded HarvardConnection (later renamed ConnectU) along with his brother Cameron Winklevoss and a Harvard classmate of theirs, Divya Narendra. In 2004, the Winklevoss brothers sued Mark Zuckerberg, claiming he stole their ConnectU idea to create the social networking service site Facebook. As a rower, Winklevoss competed in the men's pair rowing event at the 2008 Summer Olympics with his identical twin brother and rowing partner, Cameron.

Early life and education[edit]

Tyler Winklevoss was born in Southampton, New York, and raised in Greenwich, Connecticut.[1] He is the son of Carol (née Leonard) and Howard Winklevoss,[2][3] who is an author[4] and professor of actuarial science at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Winklevoss attended Greenwich Country Day School and graduated from Brunswick School.[5] Winklevoss studied classical piano for 12 years, beginning at age 6.[citation needed] He studied Latin and Ancient Greek in high school. During his junior year, he and his twin brother Cameron founded the crew program.[6][7]

On June 14, 2002, Winklevoss's older sister, Amanda, died from cardiac arrest induced by drug overdose.[8]

He matriculated to Harvard College in 2000 and majored in economics, earning an AB degree and graduating in 2004.[9] At Harvard, he was a member of the men's varsity crew, the Porcellian Club[10] and the Hasty Pudding Club.

In 2009, Winklevoss began a graduate business study at the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford and completed an MBA in 2010.[11] While at Oxford, he was a member of Christ Church,[12] an Oxford Blue, and rowed in the losing Blue Boat in the 156th Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race.[13][14][15]

ConnectU[edit]

In December 2002, Winklevoss, along with his brother Cameron Winklevoss and fellow Harvard classmate Divya Narendra, sought a better way to connect with fellow students at Harvard University and other universities.[16] The three conceived of a social network for Harvard students named HarvardConnection;[17] the concept ultimately expanded to other schools around the country.[18][19][20] What made ConnectU different from other social media platforms was the need to have a specific domain that matched the 'club' you were getting into, like harvard.edu. The idea was to make each school its own club, in which students could connect and be exclusive, similar to the infamous finals clubs at Harvard. In January 2003, they enlisted the help of fellow Harvard student, programmer and friend Sanjay Mavinkurve to begin building HarvardConnection.[21] Mavinkurve commenced work on HarvardConnection but departed the project in spring 2003 when he graduated and went to work for Google.[22]

After the departure of Mavinkurve, the Winklevosses and Narendra approached Narendra's friend, Harvard student and programmer Victor Gao, to work on HarvardConnection.[21] Gao, a senior in Mather House, opted not to become a partner in the venture, instead agreeing to be paid in a work for hire capacity.[20] He was paid $400 for his work on the website code during the summer and fall of 2003, when he left the project.[19]

Mark Zuckerberg[edit]

In November 2003, at the suggestion of Victor Gao, the Winklevosses and Narendra approached Mark Zuckerberg about joining the HarvardConnection team.[23] The previous HarvardConnection programmers had reportedly made progress on coding front-end pages, the registration system, a database, back-end coding, and a way users could connect with each other, which Gao called a "handshake".[20] In early November, Narendra emailed Zuckerberg saying, "We're very deep into developing a site which we would like you to be a part of and ... which we know will make some waves on campus."[20] Within days, Zuckerberg was talking to the HarvardConnection team and preparing to take over programming duties from Gao.[20] On the evening of November 25, 2003,[24] the Winklevosses and Narendra met with Zuckerberg in the dining hall of Harvard's Kirkland House, where they explained to Zuckerberg the HarvardConnection website, the plan to expand to other schools after launch, the confidential nature of the project, and the importance of getting there first.[18][20] During the meeting, Zuckerberg allegedly entered into an oral contract with Narendra and the Winklevosses and became a partner in HarvardConnection.[25] He was given the private server location and password for the unfinished HarvardConnection website and code,[19] with the understanding that he would finish the programming necessary for launch.[26] Zuckerberg allegedly chose to be compensated through an interest in the enterprise (sweat equity).[27]

On November 30, 2003, Zuckerberg told Cameron Winklevoss in an email that he did not expect completion of the project to be difficult. Zuckerberg writes: "I read over all the stuff you sent and it seems like it shouldn't take too long to implement, so we can talk about that after I get all the basic functionality up tomorrow night."[23] The next day, on December 1, 2003, Zuckerberg sent another email to the HarvardConnection team. "I put together one of the two registration pages so I have everything working on my system now. I'll keep you posted as I patch stuff up and it starts to become completely functional."[18] On December 4, 2003, Zuckerberg writes: "Sorry I was unreachable tonight. I just got about three of your missed calls. I was working on a problem set."[18] On December 10, 2003: "The week has been pretty busy thus far, so I haven't gotten a chance to do much work on the site or even think about it really, so I think it's probably best to postpone meeting until we have more to discuss. I'm also really busy tomorrow so I don't think I'd be able to meet then anyway."[18] A week later: "Sorry I have not been reachable for the past few days. I've basically been in the lab the whole time working on a cs problem set which I'm still not finished with."[18] On December 17, 2003,[24] Zuckerberg met with the Winklevosses and Narendra in his dorm room, allegedly confirming his interest and assuring them that the site was almost complete.[20] On the whiteboard in his room, Zuckerberg allegedly had scrawled multiple lines of code under the heading "Harvard Connection," however, this would be the only time they saw any of his work.[20] On January 8, 2004, Zuckerberg emailed to say he was "completely swamped with work [that] week" but had "made some of the changes ... and they seem[ed] to be working great" on his computer. He said he could discuss the site starting the following Tuesday, on January 13, 2004.[23][28] On January 11, 2004, Zuckerberg registered the domain name thefacebook.com.[29] On January 12, 2004, Zuckerberg e-mailed Eduardo Saverin, saying that the Facebook site [thefacebook.com] was almost complete and that they should discuss marketing strategies.[20] Two days later, on January 14, 2004,[24] Zuckerberg met again with the HarvardConnection team; however, he allegedly failed to disclose registering the domain name thefacebook.com or developing a competing social networking website. Rather, he allegedly reported progress on HarvardConnection, told the team he would continue to work on it, and would email the group later in the week.[23] On February 4, 2004, Zuckerberg launched thefacebook.com, a social network for Harvard students, designed to expand to other schools around the country.[26]

On February 6, 2004, the Winklevosses and Narendra first learned of thefacebook.com while reading a press release in the Harvard student newspaper The Harvard Crimson.[20] According to Gao, who looked at the HarvardConnection code afterward, Zuckerberg had left the HarvardConnection code incomplete and non-functional, with a registration that did not connect with the back-end connections[clarification needed].[21] On February 10, 2004, the Winklevosses and Narendra sent Zuckerberg a cease and desist letter.[30] They also lodged a complaint with the Harvard administration regarding what they viewed as a violation of the university's honor code and student handbook.[31] The Harvard Administrative Board and university president Larry Summers reportedly viewed the matter to be outside of the university's jurisdiction.[26] President Summers advised the HarvardConnection team to take their matter to the courts.[28]

Leaked instant messages[edit]

Between November 30, 2003, and February 4, 2004, Zuckerberg exchanged a total of 52 emails with the Harvard Connection team and engaged in multiple in-person meetings.[28] During the same period of time, Zuckerberg engaged in multiple electronic instant message communications with people outside of the HarvardConnection team. On March 5, 2010, certain electronic instant messages from Mark Zuckerberg's hard drive were leaked to the public.[18] On September 20, 2010, Facebook confirmed the authenticity of these leaked instant messages in a New Yorker article.[32]

The HarvardConnection team subsequently allegedly formed a partnership The Winklevoss Chang Group with i2hub, joining the popular peer-to-peer service with ConnectU. The partnership promoted their properties through bus advertisements and press releases. i2hub integrated its popular software with ConnectU's website as part of the partnership. The team also jointly launched several projects and initiatives.[33][34]

Facebook lawsuits[edit]

In 2004, ConnectU filed a lawsuit against Facebook alleging that creator Mark Zuckerberg had broken its oral contract. The suit alleged that Zuckerberg had copied ConnectU's idea[35][36] and illegally used source code intended for the website Zuckerberg was hired to develop.[28][37][38][39] Facebook countersued with respect to Social Butterfly, a Winklevoss Chang Group project. The countersuit named among the defendants ConnectU, Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, Divya Narendra, and Wayne Chang, founder of i2hub.[40] An agreement settling both cases was reached in February 2008, with the Winklevoss party receiving $20 million in cash and $45 million in Facebook stock.[41][42] In May 2010, however, ConnectU accused Facebook of misrepresenting the value of the stock that it turned over to the ConnectU plaintiffs as part of the settlement and sought to void the settlement. ConnectU alleged that the value of the stock was $11 million rather than $45 million, as represented by Facebook at the time of settlement.[41] As a result, the total settlement value would have been $31 million, rather than the $65 million reported.[43][44] On August 26, 2010, the New York Times reported that Facebook shares were then trading at $76 per share in the secondary market, putting the value of the total settlement at close to $120 million.[45][46] If the lawsuit to revise the settlement were to succeed, the settlement value would rise to $466 million.[47] In April 2011, Ninth Circuit judge Alex Kozinski opined that "[a]t some point, litigation must come to an end. ... That point has now been reached." The twins' lawyer stated that they would seek a rehearing with the entire appeals court bench.[48] In June 2011 it was announced that a decision to pursue the case in the Supreme Court had been withdrawn.[49]

Quinn Emanuel lawsuits[edit]

One of ConnectU's law firms, Quinn Emanuel, inadvertently disclosed the confidential settlement amount in marketing material by printing "WON $65 million settlement against Facebook".[50] Quinn Emanuel sought $13 million as its contingency fee related to the original settlement. ConnectU fired Quinn Emanuel and sued the law firm for malpractice.[51] On August 25, 2010, an arbitration panel ruled that Quinn Emanuel "earned its full contingency fee." The panel also found that Quinn Emanuel committed no malpractice.[52]

The Winklevoss Chang Group lawsuit[edit]

On December 21, 2009, i2hub founder Wayne Chang and The i2hub Organization launched a lawsuit against ConnectU and its founders, Cameron Winklevoss, Tyler Winklevoss, and Divya Narendra, seeking 50% of the settlement proceeds from the original lawsuit. The complaint says "The Winklevosses and Howard Winklevoss filed [a] patent application, U.S. Patent Application No 20060212395, on or around March 15, 2005, but did not list Chang as a co-inventor. It also states "Through this litigation, Chang asserts his ownership interest in The Winklevoss Chang Group and ConnectU, including the settlement proceeds."[34] Lee Gesmer of Gesmer Updegrove, LLP posted the detailed 33-page complaint online.[33][53]

On May 13, 2011, it was reported that Judge Peter Lauriat made a ruling against the Winklevosses. Chang's case against them could proceed. The Winklevosses had argued that the court lacks jurisdiction because the settlement with Facebook has not been distributed and therefore Chang hasn't suffered any injury. Judge Lauriat wrote, "The flaw in this argument is that defendants appear to conflate loss of the settlement proceed with loss of rights. Chang alleges that he has received nothing in return for the substantial benefits he provided to ConnectU, including the value of his work, as well as i2hub's users and goodwill." Lauriat also wrote that, although Chang's claims to the settlement are "too speculative to confer standing, his claims with respect to an ownership in ConnectU are not. They constitute an injury separate and distinct from his possible share of the settlement proceeds. The court concludes that Chang has pled sufficient facts to confer standing with respect to his claims against the Winklevoss defendants."[54][55][56][57][58][59]

Rowing[edit]

Winklevoss began rowing at the age of 15, encouraged by family friends and the example of a neighbor, Ethan Ayer, who rowed at Harvard University and Cambridge University.[6] He began rowing at the Saugatuck Rowing Club on the Saugatuck River in 1997.[60] His first coach was Irishman James Mangan who coached him and his brother throughout high school.[61] Winklevoss's high school did not have a crew. In his junior year, he and his identical twin brother, Cameron Winklevoss, co-founded the crew program at their high school.[6] In the summer of 1999, he earned a place in the United States Junior National Rowing Team, competing in the coxed pair event with his brother at the World Rowing Junior Championships in Plovdiv, Bulgaria.[61]

Tyler's rowing discipline is sweep rowing.[62] He has identified Italian cyclist Mario Cipollini and Italian rowers the Abbagnale brothers (Agostino Abbagnale and Giuseppe Abbagnale) as the most influential people in his sporting career.[60]

Harvard[edit]

Winklevoss rowed at Harvard for four years, under coach Harry Parker.[7] In 2004, he sat 5-seat in the "engine room" of the Harvard men's varsity heavyweight eight boat.[61] The 2004 crew was nicknamed the "God Squad" because, according to Winklevoss, some of them believed in God while the rest believed they were god.[63] As a Harvard Crimson in 2004, he helped the "God Squad" win the Eastern Sprints, the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championship, and the Harvard–Yale Regatta to complete an undefeated collegiate racing season.[64]

In the summer of 2004, Winklevoss and the "God Squad" traveled to Lucerne, Switzerland to compete in the Lucerne Rowing World Cup. They defeated the 2004 British and French Olympic eight boats in the semi-final to earn a spot in the grand-final, in which they placed 6th.[65] The team then traveled to the Henley Royal Regatta where they competed in the Grand Challenge Cup. Winklevoss helped his team defeat the Cambridge University Blue Boat in the semi-final before they fell to the Dutch Olympic eight boat team (of the Hollandia Roeiclub) in the final by 2⁄3 of a boat length.[66] The Dutch team went on to win the Olympic silver medal at the Athens Olympic Games a month later.[67]

2007 Pan American Games[edit]

In 2007, Winklevoss was named to the United States Pan American Team and competed at the 2007 Pan American Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[68] He won a silver medal in the men's coxless four event[69] and stroked the men's eight boat to a gold medal on the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas.[70]

2008 Olympic Games[edit]

In 2008, Winklevoss was named to the United States Olympic Team and competed at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, China.[71] He rowed with his brother in the men's coxless pair event which took place at the Shunyi Olympic Rowing-Canoeing Park. The brothers were coached by the renowned Ted Nash.[7] In their first heat, they failed to finish in the top three and did not qualify for the Semifinals. In the repechage (a last chance to make the semifinals), they took first place, advancing them to the semifinals. A strong finish in semifinal 2 put them in the final competition. They ended up finishing sixth out of the fourteen countries which had qualified for the Olympics.[72]

Winklevoss Capital Management[edit]

In 2012, Tyler and his brother Cameron founded Winklevoss Capital Management, a firm that invests across multiple asset classes with an emphasis on providing seed funding and infrastructure to early-stage startups. The company is headquartered in New York's Flatiron District.

Gemini[edit]

In 2014, Tyler and his brother Cameron founded Gemini, a digital currency exchange and custodian that allows customers to buy, sell, and store digital assets. It is a New York trust company that is regulated by the SEC.

In January 2022, Gemini began sponsoring Real Bedford F.C., an English non-league football club owned by bitcoin podcaster Peter McCormack; in April 2024 the Winklevoss twins were announced as co-owners of the club following a major investment.[73]

Popular culture[edit]

Tyler and his brother Cameron are both played by actor Armie Hammer in The Social Network (2010), a film directed by David Fincher about the founding of Facebook. Actor Josh Pence was the body double for Tyler with Hammer's face superimposed.

The twins were depicted on the animated television show The Simpsons in the eleventh episode of Season 23 in the episode called "The D'oh-cial Network" which aired on January 15, 2012. The Winklevoss twins are seen rowing in the 2012 Olympic Games against Marge Simpson's sisters Patty and Selma. There is a reference made to the $65 million Facebook settlement.[74]

Tyler and Cameron are featured as the main protagonists in the 2019 book Bitcoin Billionaires: A True Story of Genius, Betrayal, and Redemption.[75]

References[edit]

- ^ "Tyler Winklevoss Athlete Bio". NBCOlympics.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Chamoff, Lisa (27 March 2010). "Friendships forged in devastating nor'easter". GreenwichTime.com.

- ^ "The Wave". The Rockaway Wave. 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Winklevoss Technologies About Us". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Gustafson, Colin (16 August 2010). "Twins back in spotlight with upcoming Facebook film". GreenwichTime.com.

- ^ a b c Riley, Cailin (10 July 2008). "Twin rowers headed to Olympics". 27east.com. The Southampton Press. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Matson, Barbara (27 July 2008). "Rowing Machines: Winklevoss twins hope to form successful pair in Beijing". The Boston Globe – via Boston.com.

- ^ "In One of the Stars You Have Been Singing". Medium. 29 July 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Kidd, Patrick (15 January 2010). "'Facebook twins' Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss offer Oxford experience in Boat Race". The Times. London.

- ^ Mezrich, Ben (2009). The Accidental Billionaires. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 28.

- ^ Betts, Hannah (20 March 2010). "Muscle-bound, Oxford-educated and multi-millionaires-meet the Winklevoss twins". The Times. London.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (3 March 2010). "Is there anything the Winklevoss twins can't do?". The Independent. London.

- ^ Rossingh, Danielle (1 April 2010). "Harvard Twins Who Sue Facebook Now Take on Cambridge in 156th Boat Race". Bloomberg.

- ^ Whittle, Natalie (5 March 2010). "Social networking pioneers...and killer oarsmen". Financial Times.

- ^ "Cambridge surprise favourites Oxford to win the 156th Boat Race". The Guardian. 3 April 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Bourne, Claire (23 November 2004). "Web sites click on campus". USA Today.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (12 August 2007). "Who owns the concept if no one signs the papers?". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carlson, Nicholas (5 March 2010). "At Last--The full story of how Facebook was founded". The Business Insideer.

- ^ a b c ConnectU, Inc. v. Facebook, Inc. et al, Declaration of Victor Gao (Massachusetts Federal Court 2007-09-21), Text.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j O'Brien, Luke (3 December 2007). "Polking Facebook". 02138 Magazine.

- ^ a b c McGinn, Timothy (28 May 2004). "Online facebooks duel over tangled web of authorship". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Richtel, Matt (11 April 2009). "Tech recruiting clashes with immigration rules". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d "Facebook accused of stealing idea". The Daily Free Press, Boston University. 9 September 2004.

- ^ a b c ConnectU, Inc. v. Facebook, Inc. et al, Complaint against all defendants, filed by Connectu, Inc. (Massachusetts Federal Court 2007-03-28), Text.

- ^ Bombardieri, Marcella (17 September 2004). "Online Adversaries: Rivalry between college-networking websites spawns lawsuit". The Boston Globe.

- ^ a b c Sharif, Shirin (5 August 2004). "Harvard grads face off against thefacebook.com". The Stanford Daily. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010.

- ^ Milcetich, Jess (16 March 2005). "Thefacebook.com faces lawsuit from rival site". The Diamondback, University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d Maugeri, Alexander (20 September 2004). "TheFacebook.com faces lawsuit". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ "WHOIS Lookup thefacebook.com". Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Glenn, Malcolm (27 July 2007). "For now, Facebook foes continue fight against site". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Hale, David (6 October 2004). "Facebook faces litigation over design concept". The Daily Orange. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010.

- ^ Vargas, Jose (20 September 2010). "The face of facebook". The New Yorker.

- ^ a b Lee Gesmer (18 January 2010). "Chang v. Winklevoss Complaint". Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- ^ a b Caroline McCarthy (4 January 2010). "Fresh legal woes for ConnectU founders". CNET News. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Levenson, Michael (27 June 2008). "Facebook, ConnectU settle dispute:Case an intellectual property kerfuffle". Boston Globe.

- ^ Glenn, Malcom A. (27 July 2007). "For Now, Facebook Foes Continue Fight Against Site". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ O'Brien, Luke (November–December 2007). "Poking Facebook". 02138. p. 66. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ McGinn, Timothy J. (13 September 2004). "Lawsuit Threatens To Close Facebook". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Tryhorn, Chris (25 July 2007). "Facebook in court over ownership". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ "The Facebook, Inc. v. Connectu, LLC et al". California Northern District Court. 9 March 2007 – via Justia.

- ^ a b Helft, Miguel (30 December 2010). "Winklevoss Twins' Facebook Fight Rages On". The New York Times.

- ^ Stone, Brad (28 June 2008). "Judge Ends Facebook's Feud With ConnectU". The New York Times.

- ^ Thomas, Owen (19 May 2010). "Facebook CEO's latest woe: accusations of securities fraud". VentureBeat.com.

- ^ Farrell, Nick (21 May 2010). "Facebook's Zuckerberg faces security fraud allegation". TechEye.net. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Investors Value Facebook at Up to $33.7 Billion". The New York Times. 26 August 2010.

- ^ Eldon, Eric (12 February 2009). "Financial wrinkle lost ConnectU some Facebook settlement dollars". VentureBeat.com.

- ^ Thomas, Owen (19 May 2010). "Facebook CEO's latest woe: accusations of securities fraud". VentureBeat.com.

- ^ Morrison, Scott (12 April 2011). "Winklevoss Twins Can't Back Out of Deal on Facebook, Judge Says". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil (22 June 2011). "Winklevoss twins finally give up fighting Facebook". ZDNet. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Dan Slater (10 February 2009). "Quinn Emanuel Inadvertently Discloses Value of Facebook Settlement". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Zusha Elinson (10 February 2010). "Quinn Emanuel Brochure Spills Value of Confidential Facebook Settlement". The Recorder.

- ^ Nate Raymond (15 September 2010). "Arbitrators Confirm Quinn Emanuel's Fee in Facebook Settlement". The National Law Journal.

- ^ Lee Gesmer (18 January 2010). "The Road Goes on Forever, But the Lawsuits Never End: ConnectU, Facebook, Their Entourages". Mass Law Blog.

- ^ Bianca Bosker (13 May 2011). "Wayne Chang's Suit Against Winklevoss Twins Can Proceed, Judge Rules". Huffington Post.

- ^ Sheri Qualters (13 May 2011). "Winklevoss Twins Loses Again in Court". The National Law Journal.

- ^ "Winklevoss Twins Sued For Part Of Their Facebook Fortunes". Fox News. 13 May 2011.

- ^ Nick O'Neill (13 May 2011). "Developer Sues Winklevoss Twins, Everybody Cheers". AllFacebook.

- ^ Chloe Albanesius (13 May 2011). "Winklevoss Twins Face Lawsuit Over Facebook Funds". PC Magazine.

- ^ Sophia Pearson (13 May 2011). "Winklevoss Twins Face Suit Over Failed Alliance, Judge Says". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b "Tyler Winklevoss Athlete Bio". USRowing.org. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Berg, Aimee (26 July 2008). "Rowing Twins Take Control". TeamUSA.org. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010.

- ^ "Tyler Winklevoss Athlete Bio". TeamUSA.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Saint Sing, Susan. The Eight: A Season in the Tradition of Harvard Crew. p. 52.

- ^ McGinn, Timothy (10 June 2004). "Team of the Year: Harvard Heavies Rout All Comers, Crimson caps second undefeated season with another national title". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ McGinn, Timothy (2 July 2004). "M. Heavyweight Crew Downs U.K., France: Crimson takes sixth at World Cup". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ McGinn, Timothy (9 July 2004). "Dutch Edge Out Harvard First Varsity". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ "Men's Eight 2004 Olympic Games Results". WorldRowing.com. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "USRowing 2007 Pan American Games Roster Announcement". USRowing.com. 26 June 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Pan American Games Results". LA Times. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Pan American Games Results". San Diego Union-Tribune. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "Meet Team USA". USA Today. 2 August 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ "2008 Summer Olympics Rowing Results". ESPN. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ Fullbrook, Danny (12 April 2024). "Billionaire twins invest in ninth-tier football club". BBC News. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "Winklevoss twins pitch plan to regulate digital money". Business Times. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Mezrich, Ben (21 May 2019). Bitcoin Billionaires: A True Story of Genius, Betrayal, and Redemption. Flatiron Books. p. 288. ISBN 978-1250217745.

External links[edit]

- 1981 births

- Living people

- American male rowers

- Rowers at the 2008 Summer Olympics

- Olympic rowers for the United States

- Oxford University Boat Club rowers

- People from Southampton (town), New York

- American computer businesspeople

- American Internet celebrities

- American information technology businesspeople

- Harvard Crimson rowers

- Identical twins

- Brunswick School alumni

- Alumni of Saïd Business School

- Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

- American twins

- Winklevoss family

- Harvard College alumni

- People associated with cryptocurrency

- Rowers at the 2007 Pan American Games

- Medalists at the 2007 Pan American Games

- Pan American Games gold medalists for the United States in rowing

- Pan American Games silver medalists for the United States in rowing

- American soccer chairmen and investors

- Chairmen and investors of football clubs in England