Theology of Martin Luther

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Christian theology |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Lutheranism |

|---|

|

The theology of Martin Luther was instrumental in influencing the Protestant Reformation, specifically topics dealing with justification by faith, the relationship between the Law and Gospel (also an instrumental component of Reformed theology), and various other theological ideas. Although Luther never wrote a systematic theology or a "summa" in the style of St. Thomas Aquinas, many of his ideas were systematized in the Lutheran Confessions.

Justification by faith[edit]

"This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification," insisted Luther, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness."[1] Lutherans tend to follow Luther in this matter. For the Lutheran tradition, the doctrine of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone is the material principle upon which all other teachings rest.[2]

Luther came to understand justification as being entirely the work of God. Against the teaching of his day that the believers are made righteous through the infusion of God's grace into the soul, Luther asserted that Christians receive that righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ, it actually is the righteousness of Christ, and remains outside of us but is merely imputed to us (rather than infused into us) through faith. "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," said Luther. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ".[3] Thus faith, for Luther, is a gift from God, and ". . .a living, bold trust in God's grace, so certain of God's favor that it would risk death a thousand times trusting in it."[4] This faith grasps Christ's righteousness and appropriates it for itself in the believer's heart.

Luther's study and research led him to question the contemporary usage of terms such as penance and righteousness in the Roman Catholic Church. He became convinced that the church had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity — the most important being the doctrine of justification by faith alone. He began to teach that salvation is a gift of God's grace through Christ received by faith alone.[5] As a result of his lectures on the Psalms and Paul the Apostle's Epistle to the Romans, from 1513–1516, Luther "achieved an exegetical breakthrough, an insight into the all-encompassing grace of God and all-sufficient merit of Christ."[6] It was particularly in connection with Romans 1:17 "For therein is the righteousness of God revealed from faith, to faith: as it is written: 'The just shall live by faith.'" Luther came to one of his most important understandings, that the "righteousness of God" was not God's active, harsh, punishing wrath demanding that a person keep God's law perfectly in order to be saved, but rather Luther came to believe that God's righteousness is something that God gives to a person as a gift, freely, through Christ.[7] "Luther emerged from his tremendous struggle with a firmer trust in God and love for him. The doctrine of salvation by God's grace alone, received as a gift through faith and without dependence on human merit, was the measure by which he judged the religious practices and official teachings of the church of his day and found them wanting."[7]

Luther explained justification this way in his Smalcald Articles:

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24-25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23-25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law, or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us...Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[8]

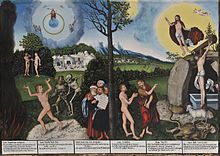

Law and Gospel[edit]

Another essential aspect of his theology was his emphasis on the "proper distinction"[9] between Law and Gospel. He believed that this principle of interpretation was an essential starting point in the study of the scriptures and that failing to distinguish properly between Law and Gospel was at the root of many fundamental theological errors.[10]

Universal priesthood of the baptized[edit]

Luther developed his expositions of the "universal priesthood of believers" from New Testament scripture. Through his studies, Luther recognized that the hierarchical division of Christians into clergy and laity, stood in contrast to the Apostle Peter's teaching (1Peter 2:1-10).

. . . 9But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light. 10Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.

Simul justus et peccator[edit]

(Latin simul, "simultaneous" + Latin justus, "righteous" + Latin et, "and" + Latin peccator, "sinner")[11] Roman Catholic theology maintains that baptism washes away original sin. However, "concupiscence" remains as an inclination to sin, which is not sin unless actualized.[12] Luther and the Reformers, following Augustine, insisted that what was called "concupiscence" was actually sin. While not denying the validity of baptism, Luther maintains that the inclination to sin is truly sin.[13]

Simul justus et peccator means that a Christian is at the same time both righteous and a sinner. Human beings are justified by grace alone, but at the same time they will always remain sinners, even after baptism. The doctrine can be interpreted in two different ways. From the perspective of God, human beings are at the same time totally sinners and totally righteous in Christ (totus/totus). However, it would also be possible to argue that human beings are partly sinful and partly righteous (partim/partim). The doctrine of simul justus is not an excuse for lawlessness, or a license for continued sinful conduct; rather, properly understood, it comforts the person who truly wishes to be free from sin and is aware of the inner struggle within him. Romans 7 is the key biblical passage for understanding this doctrine.

Luther also does not deny that the Christian may ever "improve" in his conduct. Instead, he wishes to keep Christians from either relying upon or despairing because of their own conduct or attitude.

18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant's doctrine of radical evil has been described as an adaptation of the Lutheran simul justus et peccator.[14]

Sacraments and the means of grace[edit]

Two Kingdoms[edit]

Martin Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms (or two reigns) of God teaches that God is the ruler of the whole world and that he rules in two ways, both by the law and by the gospel.

God rules the earthly kingdom through secular government, by means of law and the sword. As creator, God would like to promote social justice, and this is done through the political use of the law. At the same time, God rules his spiritual kingdom in order to promote human righteousness before God. This is done through the gospel, according to which all humans are justified by God's grace alone.

This distinction has in Lutheran theology often been related to the idea that there is no particular Christian contribution to political and economic ethics. Human reason is enough to understand what is a right act in political and economic life. The gospel does not give any contribution to the content of social ethics. From this perspective Lutheran theology has often supported those in political and economic power.

New Finnish School[edit]

Finnish scholarship in recent years has presented a distinctive view of Luther. Tuomo Mannermaa at the University of Helsinki led "The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther" that presents Luther's views on salvation in terms much closer to the Eastern Orthodox doctrine of theosis rather than established interpretations of German Luther scholarship.[15]

Mannermaa's student Olli-Pekka Vainio has argued that Luther and other Lutherans in the sixteenth century (especially theologians who later wrote the Formula of Concord) continued to define justification as participation in Christ rather than simply forensic imputation. Vainio concludes that the Lutheran doctrine of justification can deny merit to human actions, "only if the new life given to the sinner is construed as participation in the divine Life in Christ. . . . The faith that has Christ as its object, and which apprehends Him and His merit, making Him present as the form of faith, is reckoned as righteousness".[16]

The Finnish approach argues that it is due to a much later interpretation of Luther that he is popularly known as centering his doctrine of human salvation in the belief that people are saved by the imputation to them of a righteousness not their own, Christ's own ("alien") righteousness. This is known as the theological doctrine of forensic justification. Rather, the Finnish School asserts that Luther's doctrine of salvation was similar to that of Eastern Orthodoxy, theosis (divinization). The Finnish language is deliberately borrowed from the Greek Orthodox tradition, and thus it reveals the intention and context of this theological enterprise: it is an attempt by Lutherans to find common ground with Orthodoxy, an attempt launched amid the East-West détente of the 1970s, but taking greater impetus in a post-1989 world as such dialogue appears much more urgent for churches around the Baltic.[17]

The New Finnish Interpretation has been challenged because it ignores Luther's roots and theological development in Western Christendom, and it characterizes Luther's teaching on Justification as based on Jesus Christ's righteousness which indwells the believer rather than his righteousness as imputed to the believer.[18] Kolb and Arand (2008) argue that, "These views ignore the radically different metaphysical base of Luther's understanding and that of the Eastern church, and they ignore Luther's understanding of the dynamic, re-creative nature of God's Word."[19] In the anthology Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther the topic of Osiandrianism is addressed because the Finnish School is perceived as a repristination of Andreas Osiander's doctrine of salvation through Christ's indwelling the believer with his divine nature.

Demonology[edit]

Luther continued a tradition of Christian engagement with the demonic from his medieval predecessors. For instance, during his Table Talks, he references Mechthild of Magedburg's The Flowing Light of the Godhead, an example of the pre-reformation piety which Luther was immersed in that associate the Devil with excrement. Luther references Mechtihild's work, suggesting that those in a state of mortal sin are eventually excreted by the Devil.[20] Joseph Smith states that Luther's advice regarding the Devil, is "that one should address the devil as such" quoting:

"Devil, I also shat into my pants, did you smell it, and did you record it with my others sins?’ (Tischreden 261,b)

Other instances include him rehearsing medieval scatalogical limericks:

Devil: You monk on the latrine,

you may not read the matins here!

Monk: I am cleansing my bowels

and worshipping God Almighty;

You deserve what descends

and God what ascends."[21]

He separately states:

Reader, be commended to God, and pray for the increase of preaching against Satan. For he is powerful and wicked, today more dangerous than ever before because he knows that he has only a short time left to rage.[21]

See also[edit]

- Apology of the Augsburg Confession

- Augsburg Confession

- Book of Concord

- Criticism of Protestantism

- Formula of Concord

- Luther's Large Catechism

- Luther's Small Catechism

- Lutheran Mariology

- Sacramental union

- Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

Further reading[edit]

- Althaus, Paul. The theology of Martin Luther (1966) 464 pages

- Bagchi, David, and David C. Steinmetz, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Reformation Theology (2004) 289 pp.

- Bainton, Roland H. Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (1950) 386 pages

- Bayer, Oswald, Martin Luther's Theology: A Contemporary Interpretation (2008) 354 pages

- Brendler, Gerhard. Martin Luther: theology and revolution (1991) 383 pages

- Gerrish, B. A. Grace and Reason: A Study in the Theology of Luther (2005) 188 pages

- Kolb, Robert. Bound Choice, Election, and Wittenberg Theological Method: From Martin Luther to the Formula of Concord. (2005) 382 pp.

- Kramm, H. H. The Theology of Martin Luther (2009) 152 pages

- Lehninger, Paul. Luther and theosis: deification in the theology of Martin Luther (1999) 388 pages

- McKim, Donald K., ed. The Cambridge companion to Martin Luther (2003) 320 pages

- Osborne, Thomas M. "Faith, Philosophy, and the Nominalist Background to Luther's Defense of the Real Presence," Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 63, Number 1, January 2002, pp. 63–82

- Paulson, Steven D., Luther for Armchair Theologians (2004) 208 pages

- Trigg, Jonathan D. Baptism in the theology of Martin Luther (2001) 234 pages

- Wengert, Timothy J. The Pastoral Luther: Essays on Martin Luther's Practical Theology (2009) 380 pages

- Zachman, Randall C. The Assurance Of Faith: Conscience In The Theology Of Martin Luther And John Calvin (2005), 272pp

Notes[edit]

- ^ Herbert Bouman, "The Doctrine of Justification in the Lutheran Confessions," Concordia Theological Monthly 26 (November 1955) No. 11:801."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Herbert J. A. Bouman, "The Doctrine of Justification," 801-802.

- ^ "Martin Luther's Definition of Faith". projectwittenberg.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Preface to Romans by Martin Luther". www.ccel.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Markus Wriedt, "Luther's Theology," in The Cambridge Companion to Luther (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 88-94.

- ^ Lewis W. Spitz, The Renaissance and Reformation Movements, Revised Ed. (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1987), 332.

- ^ a b Spitz, 332.

- ^ Martin Luther, The Smalcald Articles in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005), 289, Part two, Article 1.

- ^ Ewald Plass, "Law and Gospel", in What Luther Says: An Anthology (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959), 2:732, no. 2276

- ^ Preus, Robert D. "Luther and the Doctrine of Justification" Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine Concordia Theological Quarterly 48 (1984) no. 1:11-12.

- ^ "Simul justus et peccator | Theological Word of the Day". Archived from the original on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, 4.4 (30)

- ^ Apology of the Augsburg Confession 2.38-41

- ^ Patrick Frierson (2007) Providence And Divine Mercy In Kant's Ethical Cosmopolitanism, Faith and Philosophy Volume 24, Issue 2, April 2007, page 151

- ^ See Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson, eds. Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther (1998); also Ted Dorman, Review of "Union With Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther". First Things, 1999. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ^ Olli-Pekka Vainio, Justification and Participation in Christ: The Development of Justification from Luther to the Formula of Concord (1580) Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions (Leiden: Brill, 2008). p 227

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, "Protestantism in Mainland Europe: New Directions," Renaissance Quarterly, Volume 59, Number 3, Fall 2006, pp. 698-706

- ^ William Wallace Schumacher, "'Who Do I Say That You Are?' Anthropology and the Theology of Theosis in the Finnish School of Tuomo Mannermaa" (Ph.D. diss., Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, 2003), 260ff.

- ^ Robert Kolb and Charles P. Arand, The Genius of Luther's Theology: A Wittenberg Way of Thinking for the Contemporary Church, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2008), 48

- ^ Mechthild of Magdeburg, Das fliessende Licht der Gottheit ("The Glowing Light of the Godhead"), Chapter 3, 21 in Schmidt, Joseph with Mary Simon. "Holy and Unholy Shit: The Pragmatic Context of Scatological Curses in Early German Reformation Satire". In Fecal Matters in Early Modern Literature and Art: Studies in Scatology. Edited by Jeff Persels andRussell Ganim, 109-117. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2004. see page 170 EPUB edition

- ^ a b D. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Tischreden [Table Talk], vols. I -6 (Weimar, 1912-21). WAT no. 2307; 413, 14-19; 1531. in Oberman, Heiko Augustinus. Luther : Man Between God and the Devil New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. page 154,