The Eagle Has Landed (film)

| The Eagle Has Landed | |

|---|---|

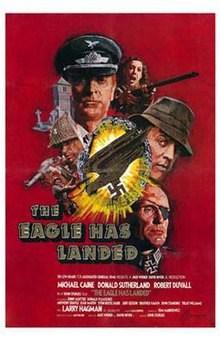

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Screenplay by | Tom Mankiewicz |

| Based on | The Eagle Has Landed by Jack Higgins |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Anthony B. Richmond |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Cinema International Corporation |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6,000,000[1] |

The Eagle Has Landed is a 1976 British war film directed by John Sturges and starring Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, and Robert Duvall.

Based on the 1975 novel The Eagle Has Landed by Jack Higgins, the film is about a fictional German plot to kidnap Winston Churchill in the middle of the Second World War. The Eagle Has Landed was Sturges's final film, and was successful upon its release.[2]

Plot[edit]

In 1943, following the successful rescue of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, Admiral Canaris, head of the Abwehr, is ordered to make a feasibility study into capturing the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. Canaris considers it a meaningless exercise that will soon be forgotten by the Führer, but he knows this will not be the case with Heinrich Himmler. Canaris therefore orders staff officer Oberst Radl to begin the study, to avoid being discredited.

Radl receives intelligence from an Abwehr sleeper agent in England, saying Churchill will stay in a Norfolk village near the coast. He begins to see potential in the operation, which he code-names "Eagle". Firstly, Radl recruits an agent, an IRA man named Liam Devlin, who lectures at a Berlin university. Secondly, he selects Kurt Steiner, a highly decorated and experienced Fallschirmjäger officer, to lead the mission. However, while the Luftwaffe parachute troops are returning from the Eastern Front, Steiner unsuccessfully attempts to save the life of a Jewish girl who is trying to escape from the SS in occupied Poland. Steiner and his loyal men are court-martialled, and sent to a penal unit on German-occupied Alderney, where their mission is to conduct near-suicidal human torpedo attacks against Allied shipping in the English Channel.

Radl is summoned to a private meeting with Himmler, without Canaris' knowledge. Himmler reveals that he knows all about the operation, and gives Radl a letter of authority, apparently signed by Hitler, authorising the operation and giving him carte blanche to use all means necessary to carry it out. He then flies to Alderney, where he recruits Steiner and his surviving men.

Operation Eagle involves the German commandos dressing as Polish paratroopers to infiltrate the village; underneath, however, they retain their German uniforms so as to avoid being shot as spies if taken prisoner. Their aim is to capture Churchill, with the help of Devlin, before making their escape by a captured motor torpedo boat. Once the operation is underway, Himmler retrieves the letter that he had given to Radl and destroys it.

On arrival in the English village, the German paratroopers take up positions under the guise of conducting friendly military exercises. However, the ruse is discovered when one of Steiner's men rescues a young girl from certain death beneath the village waterwheel. The soldier dies and the wheel brings up his mangled corpse. The villagers then see that he is wearing a German uniform underneath his Polish one. Steiner's men round up the villagers and hold them captive in the village church, but the vicar's sister, Pamela Verecker, escapes and alerts a unit of nearby United States Army Rangers.

Colonel Pitts, the Rangers’ inexperienced and rash commander, launches a poorly planned assault on the church that results in heavy American casualties. Pitts is later killed by the village's sleeper Abwehr agent, Joanna Grey. It is left to Pitts' deputy, Captain Harry Clark, to launch another attack that overruns the positions of the Germans and traps them inside the church. To delay the Americans, Steiner's men sacrifice themselves to give Devlin, Steiner, and his wounded second-in-command time to escape the church through a hidden passage. A local girl, Molly Prior, who has fallen for the charming Devlin, helps them escape. At the waiting S-boat, Steiner orders his wounded second-in-command on board, but says he is staying behind to kill Churchill.

On Alderney, Radl receives news that the operation has failed. He realises that Himmler had never really had Hitler's permission for the mission. In consequence, Radl is arrested and summarily executed by an SS firing squad under the pretext that he "exceeded his orders to the point of treason".

Back in England, Steiner succeeds in killing Churchill moments before being shot dead himself. It is then revealed that the victim was actually a body double, and that the real Churchill was on his way to the Tehran Conference. The torpedo boat is aground, at dead low tide, awaiting Steiner's return. Meanwhile Devlin, evading capture, leaves a love letter for the local girl, before slipping away.

Cast[edit]

- Michael Caine as Colonel (Oberst) Kurt Steiner

- Donald Sutherland as Liam Devlin

- Robert Duvall as Colonel (Oberst) Max Radl

- Jenny Agutter as Molly Prior

- Donald Pleasence as Heinrich Himmler

- Anthony Quayle as Admiral Wilhelm Canaris

- Jean Marsh as Joanna Grey

- Sven-Bertil Taube as Captain (Hauptmann) Hans Ritter von Neustadt

- John Standing as Philip Verecker

- Judy Geeson as Pamela Verecker

- Treat Williams as Captain Harry Clark

- Larry Hagman as Colonel Clarence E. Pitts

- Siegfried Rauch as Hauptfeldwebel Hans Brandt

- Michael Byrne as Feldwebel Karl Hofer

- Maurice Roeves as Major Corcoran

- Keith Buckley as Hauptmann Peter Geriecke

- Terry Plummer as Arthur Seymour

- John Barrett asLaker Armsby

- David Gilliam as Sergeant Moss

- Jeff Conaway as Lieutenant Frazier

- Kent Williams as Lieutenant Mallory

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

In October 1974, Paramount announced they had purchased the film rights to Jack Higgins' The Eagle Has Landed in partnership with Jack Wiener, formerly an executive at Paramount.[3] The book came out in 1975 and was a bestseller,[4] but the author had doubted whether anyone would be interested in making a film of the novel because its protagonists were German soldiers. He was amazed that the rights were not only sold within a fortnight but that the film was brought to production so swiftly.[5]

Casting[edit]

Michael Caine was originally offered the part of Devlin but did not want to play a member of the IRA, so asked if he could have the role of Steiner. Richard Harris was in line to play Devlin, but ongoing comments he had made in support of the IRA and attendance at an IRA fundraising event in America embroiled him in scandal and drew threats to the film's producers, so he was removed from the production and Donald Sutherland was given the role instead.[1][6]

In March 1976, The New York Times announced that David Bowie would play a German Nazi in the film if his schedule could be worked out.[7] Jean Marsh's role was originally offered to Deborah Kerr, who turned it down.[8]

Filming[edit]

Filming took place in 1976 over sixteen weeks.[9] Tom Mankiewicz thought the script was the best he had ever written but felt "John Sturges, for some reason, had given up" and did a poor job, and that editor Anne V. Coates was the one who saved the movie and made it watchable.[10]

Michael Caine had initially been excited at the prospect of working with Sturges. During shooting, Sturges told Caine that he only worked to earn enough money to go fishing. Caine wrote later in his autobiography: "The moment the picture finished he took the money and went. [Producer] Jack Wiener later told me [Sturges] never came back for the editing nor for any of the other good post-production sessions that are where a director does some of his most important work. The picture wasn't bad, but I still get angry when I think of what it could have been with the right director. We had committed the old European sin of being impressed by someone just because he came from Hollywood."[11]

Cornwall was used to represent the Channel Islands, and Berkshire for East Anglia.[12] The majority of the film, set in the fictional village of Studley Constable, was filmed at Mapledurham on the A4074 in Oxfordshire and features the village church, Mapledurham Watermill and Mapledurham House, which represented the manor house where Winston Churchill was taken.[12] A fake water wheel was added to the 15th-century structure for the film.[12] Mock buildings such as shops and a pub were constructed on site in Mapledurham while interiors were filmed at Twickenham Studios. The "Landsvoort Airfield" scenes were filmed at RAF St Mawgan, five miles (8 km) from Newquay.[12]

The sequence set in Alderney was filmed in Charlestown, near St Austell in Cornwall.[12] Some of the filming took place at Rock in Cornwall. The railway station sequence where Steiner and his men make their first appearance was filmed in Rovaniemi, Finland.[12] The parachuting scenes were carried out by members of the REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) Parachute Display Team on Wednesday 28 April 1976. The exit shots were filmed from a DC-3 at Dunkeswell Airfield in Devon. The landings onto the beach were filmed on Holkham Beach in Norfolk.

Reception[edit]

The film was a success, with Lew Grade saying "it made quite a lot of money".[13] ITC made two more films with the same production team, Escape to Athena and Green Ice.[14] The Eagle Has Landed spent a week as the number one film in the United Kingdom (9 April 1977) and was the fifteenth-most successful film of 1977.[15]

In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby called the film "a good old-fashioned adventure movie that is so stuffed with robust incidents and characters that you can relax and enjoy it without worrying whether it actually happened or even whether it's plausible."[2] Canby singled out the writing and directing for praise:

Tom Mankiewicz's screenplay, based on a novel by Jack Higgins, is straightforward and efficient and even intentionally funny from time to time. Mr. Sturges ... obtains first-rate performances building the tension until the film's climactic sequence, which, as you might suspect, concludes with a plot twist. ... With so many failed suspense melodramas turning up these days, it's refreshing to see one made by people who know what they're about.[2]

When another ITC production, March or Die, faltered in US theatres during initial engagements in the fall of 1977, Columbia Pictures repackaged it into a double-feature combo with Eagle for its remaining playdates.

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 67%, based on reviews from 12 critics.[16] On Metacritic, it has a score of 61%, based on reviews from seven critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[17]

Home media[edit]

While US and UK VHS cassettes had the 123-minute US cut, most DVDs and Blu-rays available worldwide feature the original UK theatrical cut, which in DVD region 2 and 4 countries runs 130 minutes at 25fps (PAL speed). There are two exceptions:

- The first US (NTSC) DVD, from Artisan Entertainment, had some missing scenes reinstated for a runtime of 131 minutes. It has been superseded by a Shout! Factory Blu-ray/DVD dual format set, containing the UK theatrical cut and various extras.

- In 2004 Carlton Visual Entertainment in the UK released a two-disc Special Edition PAL DVD version, which contains various extras and two versions of the film: the UK theatrical version and a newly restored, extended 145-minute version, equivalent to 151 minutes at 24fps (film speed).[18] Although the packaging claims otherwise, both versions have a 2.0 stereo surround soundtrack.

The extended version contains a number of scenes that were deleted even before the European cinema release:[18]

- Alternative opening: originally, the film was intended to start with Heinrich Himmler (Donald Pleasence) arriving at Schloss Hohenschwangau for a conference with Hitler, Canaris, Martin Bormann and Joseph Goebbels. It precedes the scenes under the opening credits which are a long aerial shot of a staff car leaving the castle in question. The deleted scene explains why Schloss Hohenschwangau appears in the credits but not in the film.

- Extended scene in which Radl arrives at Abwehr headquarters; he discusses his health with a German Army doctor, played by Ferdy Mayne.

- Scene at the Berlin University where Liam Devlin is a lecturer.

- Scene in Landsvoort where Steiner and von Neustadt discuss the mission, its merits, and consequences.

- Extended scene of Devlin's arrival at Studley Constable in which he and Joanna Grey discuss their part in the mission.

- Scene of Devlin driving his motorbike through the centre of the village and on to the cottage, where he inspects the barn before returning to the village.

- Scene in which Devlin reads poetry to Molly Prior.

- Extended scene in which Molly interrupts Devlin shortly after he receives the army vehicles.

- Scene on the boat at the end of the film showing the fate of von Neustadt; the scene is also featured in the Special Edition DVD stills gallery.

See also[edit]

- Cultural depictions of Winston Churchill

- Went the Day Well?, a 1942 British film about German paratroopers taking over an English village

References[edit]

- ^ a b Lovell, Glenn. Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press, 2008, pp. 284–288.

- ^ a b c Canby, Vincent (26 March 1977). "The Eagle Has Landed (1976)". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ A. M. Weller, "News of the Screen: Churchill Inspires A Thriller", The New York Times, 6 October 1974: 63.

- ^ "Best Seller List", The New York Times, 10 August 1975: 202.

- ^ Carroll, Jack (March–April 2000). "Jack Higgins Has It Made And Harry Patterson Hasn't Fared Badly Either". WRITERS' Journal.

- ^ Richard Harris: Sex, Death and the Movies (2004) Michael Feeney Callan p. 267

- ^ Henry Edwards, "Bowie's Back But the Glitter's Gone", The New York Times 21 March 1976: 57. NY Times Archive

- ^ Braun, Eric (1978). Deborah Kerr. St. Martin's Press. p. 233.

- ^ Nigel Wigmore, "The roar of the director and the snap of the clapper board", The Guardian, 17 July 1976: 9.

- ^ Tom Mankiewicz and Robert Crane, My Life as a Mankiewicz, University Press of Kentucky, 2012, p. 179

- ^ Nixon, Rob. "The Eagle Has Landed". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Eagle Has Landed film locations". Movie Locations. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008.

- ^ Alexander Walker, National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and Eighties, 1985 p 197 ISBN 978-0752857077

- ^ Lew Grade, Still Dancing: My Story, William Collins & Sons, 1987, p. 250

- ^ Swern, Phil (1995). The Guinness Book of Box Office Hits. Guinness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-85112-670-7.

- ^ "The Eagle Has Landed (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "The Eagle Has Landed". Metacritic.

- ^ a b Koemmlich, Herr (22 August 2009). "The Eagle Has Landed". Movie Censorship. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

External links[edit]

- 1976 films

- 1970s thriller films

- 1970s war films

- British spy films

- British thriller films

- British war films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Winston Churchill

- Cultural depictions of Heinrich Himmler

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films directed by John Sturges

- Films set in England

- Films set in Norfolk

- Films about United States Army Rangers

- Films shot in Cornwall

- Films shot in Finland

- ITC Entertainment films

- Films with screenplays by Tom Mankiewicz

- War adventure films

- World War II spy films

- Films scored by Lalo Schifrin

- Films set in 1943

- British World War II films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s British films