Than Shwe

Than Shwe | |

|---|---|

သန်းရွှေ | |

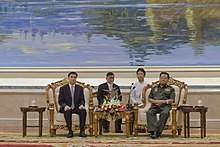

Than Shwe in 2010 | |

| Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council | |

| In office 23 April 1992 – 30 March 2011 | |

| Prime Minister | See list

|

| Deputy | Maung Aye |

| Preceded by | Saw Maung |

| Succeeded by | Thein Sein (as President) |

| Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Myanmar | |

| In office 23 April 1992 – 30 March 2011 | |

| Deputy | Maung Aye |

| Preceded by | Saw Maung |

| Succeeded by | Min Aung Hlaing |

| Prime Minister of Myanmar | |

| In office 23 April 1992 – 25 August 2003 | |

| Leader | Himself |

| Preceded by | Saw Maung |

| Succeeded by | Khin Nyunt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 February 1933[2] Kyaukse, Upper Burma, British Burma (present-day Myanmar) |

| Height | 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in) |

| Spouse | Kyaing Kyaing |

| Relations | Nay Shwe Thway Aung (grandson) |

| Children | Multiple, including: Htun Naing Shwe Kyaing San Shwe Thandar Shwe Khin Pyone Shwe Aye Aye Thin Shwe Kyi Kyi Shwe Dewa Shwe Thant Zaw Shwe |

| Alma mater | Officers Training School, Bahtoo, Frunze Military Academy (Soviet Union) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1953–2011 |

| Rank | |

Than Shwe (Burmese: သန်းရွှေ; pronounced [θáɰ̃ ʃwè]; born 2 February 1933) is a retired Burmese army general who played a role in Myanmar's political landscape.[3] As the Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), he held influential authority, contributing to a perception of centralized power.[4][5] His governance from 1992 to 2011 involved policies that some considered restrictive, alongside a notable military presence.[6][7] Than Shwe served as the head of state of Myanmar, holding the position of Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) during the same period, influencing the country's political trajectory.[8][9]

Occupying key positions, including Prime Minister of Myanmar, Commander-in-Chief of Myanmar Defence Services, and head of the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDP), Than Shwe has elicited various perspectives on his governance.[10][11][12][13] In March 2011, he officially stepped down as head of state, facilitating the transition to his chosen successor, Thein Sein.[14][15][16] As the head of the Armed Forces, he was succeeded by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.[17][18] Than Shwe continues to wield significant influence within the military.[19][20][21][22]

Early life and education[edit]

Than Shwe was born on 2 February 1933, in Minzu village, near Kyaukse, British Burma (now Myanmar), to his parents, Lay Myint and Seinn Yin.[23] His early education led him to Government High School in Kyaukse, where he completed his studies in 1949. Following his education, he began his career as a postal clerk at the Meikhtila Post Office.[24][25] However, his path shifted towards the military when he enlisted in the Burmese Army, joining the ninth intake of the Officers Training School, Bahtoo.[26]

Military career and rise to power[edit]

After graduating from the Officer Training School, Second Lieutenant Than Shwe assumed the role of a squad leader in No. 1 Infantry Battalion on 11 July 1953. Progressing through the ranks, he was promoted to platoon commander in 1955 with the rank of lieutenant.[27][28] On 21 February 1957, he advanced to the position of company commander within the same battalion, holding the rank of captain. He demonstrated early leadership and strategic capabilities during military operations in Karen State, Southern Shan State, and the Eastern Thanlwin area conducted by No. 1 Infantry Battalion.

On 26 February 1958, Than Shwe's career took an international turn as he was assigned to the newly established Directorate of Education and Psychological warfare within the War Office. Between April 1958 and November 1958, he underwent specialized army officers' training in the Soviet Union, conducted by the KGB. Subsequently, on 9 December 1961, he assumed the role of a company commander in No. 1 Psychological Warfare Battalion under Northern Regional Military Command on 9 December 1961. He later became the psychological warfare officer of the 3rd Infantry Brigade on 4 December 1961. On 18 December 1963, he was transferred to Central Political College as an instructor. He was then posted to 101 Light Infantry Battalion as a temporary company commander for the battalion headquarters unit.[29]

Promoted to the rank of major, Than Shwe joined the 77th (LID) Light Infantry Division on 27 January 1969. Between 1969 and 1971, he successfully completed the Higher Command and Staff Course at the Frunze Military Academy in the Soviet Union. During the tenure with the 77th LID, he actively participated in military operations across Karen State, Irrawaddy Delta region and Bago Hills. He was transferred to Operations Planning Department within the Office of Chief of Staff (ARMY) as a General Staff Officer (G2) on 16 December 1969. Than Shwe was nicknamed 'the bulldog' in the military.[30]

He assumed the role of a No. 1 Infantry Battalion on 23 August 1971 and earned a promotion to the rank of lieutenant colonel on 7 September 1972. As the commanding officer of No. 1 Infantry Battalion, he actively participated in offensive operations against various insurgents carried out by the 88th Light Infantry Division (LID) in the Bhamo region, Northern Shan State, Southern Shan State, and Eastern Shan State. Than Shwe was then transferred back to the Operations Planning Department within the Office of Chief of Staff (ARMY) as a General Staff Officer (G1) on 4 August 1975. On 26 March 1977, he attained the rank of a colonel and assumed the position of deputy commander of the 88th LID Light Infantry Division on 2 May 1978.[31]

On March 1980, Than Shwe became commanding officer of the 88th LID. He oversaw various operations, including Operation Ye Naing Aung, Operation Nay Min Yang, and Operation Min Yan Aung, carried out by the 88th LID. In 1981, he was elected as a member of the ruling Burma Socialist Programme Party's Central Executive Committee during the fourth session of the Party's conference.[32]

He took on the role of commanding officer at the Southern Western Regional Military Command on 22 July 1983 and subsequently became the chairman of Irrawaddy Division Party Committee on 5 August 1983. Than Shwe was promoted to brigadier general on 16 August 1984 and assumed the position of vice chief of staff (Army) on 4 November 1985.[33]

Promoted to major general on 4 November 1986 and to lieutenant general on 4 November 1987, he assumed the position of Deputy Minister of Defence on 27 July 1988.[34]

After the military coup on 18 September 1988, following the democracy uprising of 1988, Than Shwe became vice-chairman of State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), a 21-member military cabinet headed by Senior General Saw Maung. He was promoted to the rank of full general and assumed the positions of vice-commander in chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces and commander-in-chief of the Myanmar Army on 18 March 1990.[35]

On 23 April 1992, Senior General Saw Maung unexpectedly resigned, citing health reasons.[36] Than Shwe elevated himself to the rank of senior general and replaced Saw Maung as the head of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and commander-in-chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces.

Style of leadership[edit]

Than Shwe relaxed some state control over the economy, and was a supporter of Burma's participation in the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). He also oversaw a large crackdown on corruption, which saw the sackings of a number of cabinet ministers and regional commanders in 1997.

The convention for the "Discipline Democracy New Constitution" was convened from 9 January 1993 to 3 September 2007, a period of more than 14 years and 8 months. Although the main opposition party, National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi, which won the multi-party democracy general election in 1990, did not participate, the chairman of National Convention Lieutenant General Thein Sein announced that the creation of the "Constitution" had been accomplished.

Than Shwe has continued the suppression of the free press in Burma, and has overseen the detention of journalists who oppose his regime. While he oversaw the release of Aung San Suu Kyi during the late 1990s, he also oversaw her return to detention in 2003. Despite his relaxation of some restrictions on Burma's economy, his economic policies have been often criticized as ill-planned.[37][38]

He maintains a low profile, often perceived as reserved and serious, with a reputation as a hardliner and a skilled manipulator. Some observers note that he opposes the democratization of Burma.[39] He marks national holidays and ceremonies with messages in the state-run newspapers but rarely engages with the press. The lavish wedding of his daughter, involving diamonds and champagne, was particularly controversial in a country whose people continue to suffer enormous poverty and enforced austerity.[40]

Power struggles have plagued Burma's military leadership. Than Shwe has been linked to the toppling and arrest of Prime Minister Khin Nyunt in 2004, which has significantly increased his own power.[41] The former premier, who said he supported Aung San Suu Kyi's involvement in the National Convention, was seen as a moderate at odds with the junta's hardliners.

Than Shwe is said to rely heavily on advice from his soothsayers, a style of ruling dating back to General Ne Win, a leader who once shot his mirror to avoid bad luck.[42]

In May and November 2006 he met with the United Nations special envoy Ibrahim Gambari in the newly built capital of Naypyidaw, which had replaced Yangon in the previous year, and permitted Gambari to meet with Aung San Suu Kyi. However, Than Shwe refused to meet Gambari when he visited Burma in November 2007 and again on 10 March 2008.[43]

In early May 2008, Than Shwe refused many foreign aid workers from entering the country in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis (May 2, 2008).[44] This led to many criticisms from the UN as well as the international community.

In early July 2009, the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon visited Burma and held talks with Senior General Than Shwe. The military junta rejected UN Secretary General's request to meet with Aung San Suu Kyi. Than Shwe also commented on the upcoming 2010 Burmese election, saying that by the time the UN chief next visits Burma, "I will be an ordinary citizen, a lay person, and my colleagues will too because it will be a civilian government."[45]

On 27 August 2010, rumours surfaced that Than Shwe and his deputy, Vice Senior General Maung Aye, along with six other top military officers, had resigned their military posts, and that he was expected to remain head of state until at least the end of the 2011 fiscal year, when he would transfer his position to the elected president.[46] The rumor was proven false as the Burmese state media referred to him as "Senior General" three days later.[47]

Human rights controversies[edit]

Than Shwe's leadership has faced criticism for violence and human rights abuses. According to Amnesty International, human rights violation in Myanmar were described as "widespread and systematic."[48] Reports suggested that a significant number of Burmese individuals, potentially reaching up to a million, were allegedly subjected to forced labor in "jungle gulags". The absence of free speech and intolerance towards dissent were notable characteristics of the government. In 2007, during the Saffron Revolution, mass demonstrations led by Buddhist monks were suppressed by security forces, resulting in casualties and detentions.[49] Persistent rumors circulated that thousands of monks and others being rounded up and summarily executed, with their bodies reportedly dumped in the jungle.[48]

In 1998 Than Shwe ordered the execution of 59 civilians living on Christie Island. The local commander initially hesitated, expressing concerns about the issuing commander's alleged intoxication, but was informed that the instruction came from "Aba Gyi" or "Great Father"—a term used to refer to Senior General Than Shwe.[50]

Health and family[edit]

Than Shwe's wife, Kyaing Kyaing, is of Chinese and Pa'O descent. They have five daughters, Aye Aye Thit Shwe, Dewa Shwe, Khin Pyone Shwe, Kyi Kyi Shwe, and Thandar Shwe, and three sons, Kyaing San Shwe, Thant Zaw Shwe and Htun Naing Shwe.[51][52] Than Shwe is known to be a diabetic,[41] and he is rumored to have intestinal cancer.[53] Little else is known about his private life as he rarely makes public appearances or discloses personal information.[54]

Than Shwe flew to Singapore on 31 December 2006. Concerns about Than's health intensified after he failed to appear at an official Independence Day dinner for military leaders, officials, and diplomats on 4 January 2007. It was the first time since he took power in 1992 that Shwe did not host the annual dinner. Than Shwe had checked out of the Singapore General Hospital, where he had been receiving treatment, and returned to Burma two weeks later.

In 2006, a home video footage of the wedding of Than Shwe's daughter, Thandar Shwe, was leaked on the Internet, which sparked controversy and criticism from Burmese and foreign media for the lavish and seemingly ostentatious reception.[40][55] After days of Saffron Revolution, there were unconfirmed reports that Than Shwe's wife and pets fled the country on 27 September 2007, possibly to Laos.

In January 2009, Than Shwe was talked into buying one of the world's most popular football clubs, Manchester United, for $1 billion by his favourite grandson Nay Shwe Thway Aung. However, he reportedly abandoned the plan, because such an investment only months after nearly 150,000 people were killed by Cyclone Nargis was deemed inappropriate.[56]

In August 2021, Than Shwe and his wife tested positive for COVID-19. They have been warded at the 1,000-bed military-owned hospital in Thaik Chaung.[57][58]

Yadaya rituals[edit]

Than Shwe often performed superstitious yadaya rituals to maintain his power and followed the advice of astrologers and shamans. A seated jade Buddha statue that Than Shwe had carved in his image was erected in 1999 at the southern entrance of Shwedagon pagoda. It is on a list of unorthodox statues drawn up by the religious affairs ministry. Former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon and Chinese President Xi Jinping are among those who have paid respects at the statue during visits to Yangon.[59]

As a notoriously superstitious, the unusual clothing choices, namely the wearing of traditional female acheik-patterned longyi (sarongs) by Than Shwe and other military generals at public appearances, including Union Day celebrations in February 2011 and at the reception of the Lao Prime Minister Bouasone Bouphavanh in June 2011 have also been attributed to yadaya, as a way to divert power to neutralize Aung San Suu Kyi's power.[60][61]

References[edit]

- ^ by His Excellency Senior General Than Shwe Chairman of the State Law and Order Restoration Council Prime Minister of the Union of Myanmar

- ^ "Than Shwe". Alternative Asean Network on Burma. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ "Than Shwe – Myanmar soldier and politician, leader of the ruling military leadership in Myanmar (Burma) from 1992 to 2011". Britannica.

- ^ "Hearty Congratulations to Burmese Military Leader Senior General Than Shwe". Amnesty International.

- ^ Egreteau, Renaud (19 October 2009). "Born in February 1933, Senior-General Than Shwe has been the leader of the Burmese junta since 1992". SciencesPo.

- ^ Sa Tun, Aung (26 October 2023). "How a protected coastline became the private property of Than Shwe's daughters". Myanmar Now.

- ^ "Than Shwe had by now risen through the ranks of the military regime and its 'Burma Socialist Programme Party'. Born in 1933 – prior to Burma's invasion by Japan during World War Two, and its independence from Britain thereafter – he began his working life delivering mail". New Internationalist. 1 September 2005.

- ^ "Senior General Than Shwe, the Burmese military's 'old fox'". Reuters. 4 October 2007.

- ^ Nyi Nyi, Kyaw (27 October 2021). "Burmese army general Senior General Than Shwe created a sheltered Tatmadaw family. Living side by side in cantonments, soldiers train and farm. Their wives go to meetings with fellow military wives, and their children go to military-run public schools or attend schools outside in Tatmadaw trucks". East Asia Forum.

- ^ "Military Watch: Regime boss targets 'Western culture'; Than Shwe Falls From Favor; and More". The Irrawaddy. 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Whatever happened to the leader of Myanmar Senior General Than Shwe?". Southeast Asia Globe.

- ^ "For Suu Kyi and Than Shwe, an Inconvenient Truce". The Irrawaddy. 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Has former Burmese army general Than Shwe retained his influence?". Frontier Myanmar. 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Myanmar's Military Chief Staged a Coup. But He Did Not Act Alone". The Irrawaddy. 13 August 2021.

- ^ Anne, Gearan (19 May 2013). "Burma's Thein Sein says military 'will always have a special place' in government". The Washington Post.

- ^ "This political transition was a top-down approach, initiated and implemented by the regime—particularly by Than Shwe's successor, President Thein Sein, along with the vital participation of Aung San Suu Kyi in the latter stages of reform". Oxford Academic.

- ^ "Later that month, an envoy from the CCP came and met former military leader Senior General Than Shwe — now 90 years old — who had nurtured closer relations with China than Min Aung Hlaing. The envoy also met former president Thein Sein". East Asia Forum. 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar Army Chief Min Aung Hlaing Visits Former leader of Myanmar Than Shwe". The Irrawaddy. 21 April 2022.

- ^ "During his visit to Myanmar, Qin Gang also met with former Chairman of the Myanmar State Peace and Development Council Than Shwe". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China.

- ^ "Has former army leader Senior General Than Shwe retained his influence?". Frontier Myanmar. 11 September 2016.

- ^ Robert, Horn (11 April 2011). "Is Burma's leader Than Shwe Really Retiring?". TIME Magazine.

- ^ Bill, Ide (23 November 2011). "Burmese Press Mention 'Retired' Former Leader Than Shwe". Voice of America News.

- ^ "၂၀၁၅ အထွေထွေ ရွေးကောက်ပွဲ မဲဆန္ဒရှင်စာရင်း (Voter list)" (Press release). Union Election Commission. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Top 10 Sensational Facts about Than Shwe". Discover Walks. 7 August 2022.

- ^ Aung, Zaw (28 February 2013). "Every calculation and decision the opposition makes must have at its foundation an awareness of this history, because it reveals Than Shwe and his fellow generals' current propensities. And every Burma watcher, whether full-blown participant or armchair analyst, should also be familiar with the two leaders that have turned Burma into the country that it is—and is not—today". The Irrawaddy.

- ^ "Members of State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)". The Irrawaddy. 2003-11-01. Archived from the original on 2023-02-19. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ "The Day Ex-military leader Than Shwe's Reign Began". The Irrawaddy. 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Disreputable Commanders-in-Chief of the Myanmar's Military". The Irrawaddy. 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Burma's generals have a history of juggling relations with Washington and Beijing". The Irrawaddy. November 2009.

- ^ "Myanmar's military figure known as 'the bulldog'". NBC News. 2007-10-02. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Than Shwe was slowly, steadily and mostly anonymously working his way up the regime hierarchy". The Irrawaddy. 28 March 2013.

- ^ New Internationalist

- ^ "Biography of Than Shwe, Burmese senior general". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Than Shwe Consolidating Hold on Burma's Military?". Asia Sentinel. 26 August 2011.

- ^ "Shwe, Than | Sciences Po Violence de masse et Résistance - Réseau de recherche". www.sciencespo.fr (in French). 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ Wheeler, Ned (28 July 1997). "Obituary: General Saw Maung". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Independence Online Newsletter" (PDF). Shan Herald Agency for News. January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2010.

- ^ Smith, Matthew; Htoo, Naing (2008). "Energy Security: Security for Whom?". Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal.

- ^ "'The General must not be disturbed' | Democratic Voice of Burma". Dvb.no. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ a b Beaumont, Peter; Smith, Alex Duval (7 October 2007). "Drugs and astrology: how 'Bulldog' wields power". The Observer. London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ a b McCurry, Justin; Watts, Jonathan; Smith, Alex Duval (30 September 2007). "How Junta stemmed a saffron tide". The Observer. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ "Inside Burma :: DGMoen.net :: Promoting Social Justice, Human Rights, and Peace". DGMoen.net. 19 September 1988. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "How Myanmar leader snubs U.N. envoy". CNN. 11 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ "The Worst of the Worst – By George B.N. Ayittey". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Koyakutty, Haseenah (15 July 2009). "UN gains leverage over Myanmar". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009.

- ^ "Junta Chiefs Resign in Military Reshuffle". The Irrawaddy News. 27 August 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Burma's Than Shwe 'remains senior general'". BBC News. 31 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b "The world's enduring dictators". CBS News. 16 May 2011. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Johnson (2005), p. 67

- ^ "Defector tells of Burmese atrocity". www.theaustralian.com.au. 8 June 2008. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Than Shwe's Dynastic Family Dream on Parade at State Function". Irrawaddy.org. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Consolidated List Of Financial Sanctions Targets In The UK". Hm-treasury.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Than Shwe Watch". Irrawaddy.org. 10 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Burma's hardline generals". BBC News. 12 October 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Cropley, Ed (2 November 2006). "Lavish Myanmar junta wedding video sparks outrage". The Star Online. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ "Soccerleaks: The football files". CNN. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Ex-Myanmar military leader Than Shwe recovers from COVID-19". ABC News. August 24, 2021. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ "Former Myanmar strongman Than Shwe in hospital with COVID". www.aljazeera.com. 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Zaw, Aung (December 25, 2008). "Than Shwe, Voodoo and the Number 11". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Horn, Robert (2011-02-24). "Why Did Burma's Leader Appear on TV in Women's Clothes?". TIME. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ WAI MOE (2011-02-17). "Than Shwe Skirts the Issue". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

Bibliography[edit]

- Johnson, Robert (2005). A region in turmoil: South Asian conflicts since 1947. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-257-7.

External links[edit]

Media related to Than Shwe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Than Shwe at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Than Shwe at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Than Shwe at Wikiquote- Than Shwe Watch at the Irrawaddy

- Than Shwe's daughter's wedding on YouTube

- Heads of state of Myanmar

- Prime Ministers of Myanmar

- 1933 births

- Age controversies

- Burma Socialist Programme Party politicians

- Deputy Prime Ministers of Myanmar

- Burmese generals

- Living people

- People from Mandalay Region

- Frunze Military Academy alumni

- Family of Than Shwe

- Militarism

- Officers Training School, Bahtoo alumni

- Burmese anti-communists