Talk:Volt-ampere reactive

| This redirect does not require a rating on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lower case[edit]

The unit for Reactive power must be written with small characters "var" according the IEC 60027. Most publications use wrong spelling, like VAr, VAR or Var. Multiplication factors follow their own rules like kvar, Mvar, etc.

Robert. 62.92.243.245 11:39, 17 January 2007 (UTC)

VAR or var or Var[edit]

Robert is correct. Var is an ordinary word for the unit of reactive power. It is treated just like the units for other electrical quantities such as watt for active power and volt for voltage. Unlike volt, which has an abbreviation, V, there is no abbreviation for var. Another misconception is that VAR is an abbreviation for the unit voltampere reactive. I do not believe there is any such standard unit, although voltampere is a standard unit. Robert is also correct in indicating that the unit is misused in all sorts of technical publications including refereed journals. Since var is a unit not a quantity, it is technically incorrect to say something like "... capacitors produce vars ...". One should say instead that " ... capacitors produce reactive power ...". More information on this subject can be obtained by checking the entry under 'magner' in the IEEE Standard 100 (the standard dictionary). This also gives insight into where the sign on the direction of reactive power came from. Also, note that the IEEE dictionary defines watts as the unit for 'active' power, not 'effective' power. Thus, there is active, reactive, and apparent power in power system.Rcdugan 17:31, 23 June 2007 (UTC)

- I probably agree that it shouldn't be, but I suspect it is the WP:COMMONNAME by now. Anything used enough gets its own jargon, and we learn to live with it. Gah4 (talk) 19:35, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

- Actually, SI does specifically allow[1] both VA and var. It is in a footnote for power in the table. Note var and not VAR, though. Gah4 (talk) 19:45, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

References

- ^ Council Directive on units of measurements 80/181/EEC Chapter 1.2.3., p. 6: "Special names for the unit of power: the name volt–ampere (symbol ‘VA’) when it is used to express the apparent power of alternating electric current, and var (symbol ‘var’) when it is used to express reactive electric power."

November 24 2013 Edit by manishraje[edit]

I added a section on the physical significance of vars since the original was lacking in those aspects. Real, reactive and complex power are interconnected and very important. The real power is the peak value of the instantaneous power absorbed by resistive components of a circuit, while the reactive power is the magnitude of instantaneous power consumed/produced by reactive (inductive or capacitive) components. The complex power is the vector sum of the two, and it's magnitude is known as the Apparent power which is seen by a load at the receiving end. Reactive power may be in the imaginary domain, but it performs the function of voltage regulation. Without reactive power, magnetic elements (including transformers) would be unable to function. At the same time, an excess of reactive power leads to greater line losses (since line losses depend on the inductance which in turn is affected by Q) and a reduced power factor. The power factor shows the proportion of power that is consumed for actual purposes. A low power factor indicates excessive reactive power and reduced efficiency for the device. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Manishraje (talk • contribs) 01:32, 25 November 2013 (UTC)

Type of power ?[edit]

There is something profoundly wrong with this article. The entire article is premised on the mistaken idea that there can be different "types" of power, whereas in reality there can only be one - namely the average rate of transfer of energy, the average being over one complete cycle. In an AC circuit the instantaneous rate of transfer of energy (and therefore the instantaneous power) can be positive or negative at different moments in the cycle, and it is for this reason that the power is averaged over a cycle. If RMS values of current (I) and voltage (V) are used, the product VI is the value of average power (P) only in those cases where V and I are mutually in phase. In all other cases, where there is a phase angle phi, the average power is P = VIcos(phi). Thus when phi = 90deg, average power is zero even though VI might be finite. The product VI is thus not a measure of power, and it is for this reason that it is given a different name: volt-amperes or VA. The units of VA are not Watts, but simply VA. VA is a general term for the product VI in all cases. In the special case where voltage and current are in phase quadrature, and average power is zero, the product is termed volt-amperes-reactive (VAR), and the unit is VAR - again not Watts. The following statement is thus fundamentally wrong -

"The unit "var" does not follow the recommended practice of the International System of Units, because the quantity the unit var represents is power, and SI practice is not to include information about the type of power being measured in the unit name. [2]". There are no "types" of power corresponding to P, VA, and VAR; power is a completely general concept defined as rate of transfer of energy. Where there is no transfer of energy, power is zero. The idea that in an AC circuit the product VI is power (or a 'type' of power) is simply a mistake. This misunderstanding is likely to be made by a student who has learned that P = VI in a DC circuit, but has not progressed sufficiently to grasp that this is simply not true in AC circuits except in special cases.

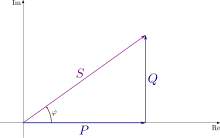

Vectorially, the complex quantity VA can be resolved into real and imaginary components corresponding to power (P) and VAR in the same way that impedance can be resolved into resistance and reactance. Note that in this latter case, the 3 quantities are also given particular names which distinguish them, and are not considered to be different "types" of resistance. However, it is perfectly correct to say that power and VAR are both 'types' of VA, just as resistance and reactance are 'types' of impedance - real and imaginary types respectively. g4oep — Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.37.54.83 (talk) 15:06, 20 May 2016 (UTC)

Edits to article mainly changing the section on Physical significance of reactive power[edit]

I suggested a change in title of the page to Reactive power instead as I will that is what the article is really talking about as opposed to the unit of measurement VAR and there is no comprehensive article on reactive power besides a small section in AC power. I added a sentence at the start about measurement of VAR by a varmeter and I wanted to submit a picture from a textbook but I guess there may be copyright issues. A more major edit was on the physical significance of reactive power. Generally, I find the original paragraph very convoluted and difficult to understand. A more important mistake, I think, is that the author seems to convey that reactive power is supplied on purpose to drive inductive loads and the failure of doing this will lead to failure to blackouts. However, I think it is better explanation would be that by virtue of the fact that most loads (transformers, motors etc) have high reactance and hence will consume reactive power due to the lagging current. The challenge electric power providers face is to balance generators and loads in such a way that reactive power is kept at the minimum to reduce line losses as well as to ensure stability of the system (stable voltage and frequency). Hence, I changed the paragraph to what I believe is a more accurate, understandable and generic explanation. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Ezrapeh (talk • contribs) 09:53, 4 December 2016 (UTC)

what electrical components cause reactive power to be consumed/generated?[edit]

OK, electric motors do -- but do they do so only when spinning freely, not under load? or only when the mechanical load is heavy? So transformers do .. does that include the transformer in my back yard, that steps down from 20KV to 120V? What about switching power supplies in my computer/TV? mercury vapor lamps? Are there any capacitative loads, anywhere, in a typical house? How about a factory? 67.198.37.16 (talk) 13:07, 20 October 2017 (UTC)

- An unloaded transformer is just an inductor, so usual inductor phase shift applies. Similarly, an unloaded motor running at full speed also looks pretty much like an inductor. Under load, a back EMF occurs, corresponding to the actual load. I believe that the unloaded reactive component stays, but becomes a smaller part of the actual load, but I never tried to compute it. A lightly loaded transformer or motor will still have a significant inductive component. Gah4 (talk) 06:47, 4 November 2017 (UTC)

This article just duplicates content already in AC power. Volt-amperes reactive are just the units in which reactive power is measured; reactive power and apparent power are already defined in AC power, which discusses them in more context, so I'd question whether this topic merits a separate article. I'd suggest merging into AC power. Failing that, I'd suggest moving it to Reactive power, as that title more accurately describes what this article is about, keeping Volt-ampere reactive as a redirect. --ChetvornoTALK 18:33, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

- Reactive power is a link into a section of AC power. I suppose I might believe that everyone who knows what AC power is, should also know about power factor and reactive power. I suspect others would disagree. Since there is an article on power factor, though, that might be a more reasonable merge. Gah4 (talk) 19:24, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

- Thinking about it more, there is electric power transmission and electric power distribution. I now suspect it would be better to redirect AC power to one of those, and rename AC power. I still believe, though, that there is enough for two articles, one giving the less technical details, and one more technical. That is, one that maybe third graders could understand, and one for more advanced readers. Gah4 (talk) 19:24, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

- I am hesitant to merge AC power (or at least the technical aspects) into a broad article like Electric power transmission or Electric power distribution that has to cover so much else. However I strongly agree about the need for nontechnical explanations for non technically educated readers (maybe not literally third grade, but middle school?). Maybe we could just write third-grade-level overview sections for the technical articles? I notice that Power factor has a lot of specialized technical content about nonlinear loads, and also must cover power factor correction gear; maybe that one should not be merged? I like the idea of merging this article into either AC power or Power factor, I'm okay with either. --ChetvornoTALK 21:56, 6 April 2019 (UTC)

- Yes, I didn't want to merge, but redirect. When most people think AC power, they think about what comes out of the wall, or the wires they see on poles. That is, that it would be the WP:COMMONNAME. I suspect that those articles cover what people would want to know. By third grade, kids should learn to plug things in, and start wondering about where the power comes from. Also, about time to learn about little transformers. Not long after that, I built my first power supply with a little filament transformer, diodes, and capacitors. But yes, maybe middle school or high school to learn about power factor and such. In any case, I believe we can have two article, with different amounts of details, on reactive power and power factor. For power factor, one doesn't have to know as much, that closer to 1 is good, and you need bigger wire with small power factor. Reactive power, and power factor correction, can get into more detail. Gah4 (talk) 00:37, 7 April 2019 (UTC)

- I'm not quite clear on your proposal. Redirect what to what? Are you proposing to have Reactive power and Power factor articles, and Introduction to reactive power and Introduction to power factor articles (as mentioned in WP:TECHNICAL) for lower level readers? --ChetvornoTALK 01:30, 7 April 2019 (UTC)

- Oppose. This article is about a unit. Merging it to AC Power is like merging kilogram to Mass. Nedim Ardoğa (talk) 14:41, 12 April 2019 (UTC)

- @Nedim Ardoğa: @Gah4: Not exactly. Kilogram is a base unit of the SI system and can support an article of its own. Volt-ampere reactive is the derived unit of reactive power, an obscure specialized quantity used only in AC electric power. In Wikipedia most similar derived units do not have their own article but are appropriately defined in the article of the relevant quantity. For example the unit of permittivity, farads per meter, does not have its own article but is defined in Permittivity. Henries per meter does not have its own article but is defined in Permeability.

- In order to explain what Volt-ampere reactive is, this article has to explain complex power to nontechnically-educated readers: real power, reactive power, apparent power and its unit Volt-ampere, voltage-current phase angle, and the power triangle. This is already explained in AC power and Power factor. This is a huge amount of redundant explanation to have to include in each separate article about these quantities. Instead why not define and explain all these quantities in one or more central articles: AC power and/or Power factor and/or Complex power? --ChetvornoTALK 11:42, 16 April 2019 (UTC)

- We have links for explaining things - leave this article as " unit of reactive power" and if a keen reader needs to know more, all the brilliant prose is only a mouse click away. --Wtshymanski (talk) 17:17, 16 April 2019 (UTC)

- I have revised this article to be much more similar to the volt ampere article. --Wtshymanski (talk) 17:27, 16 April 2019 (UTC)

- We have links for explaining things - leave this article as " unit of reactive power" and if a keen reader needs to know more, all the brilliant prose is only a mouse click away. --Wtshymanski (talk) 17:17, 16 April 2019 (UTC)

- In order to explain what Volt-ampere reactive is, this article has to explain complex power to nontechnically-educated readers: real power, reactive power, apparent power and its unit Volt-ampere, voltage-current phase angle, and the power triangle. This is already explained in AC power and Power factor. This is a huge amount of redundant explanation to have to include in each separate article about these quantities. Instead why not define and explain all these quantities in one or more central articles: AC power and/or Power factor and/or Complex power? --ChetvornoTALK 11:42, 16 April 2019 (UTC)

Merge discussion?[edit]

I might not be against the recent merge, but was there any discussion about it? The above merge discussion ended with not merge. It is nice to discuss first, as undoing the merge is more work. Anyone want to discuss it now? Gah4 (talk) 00:11, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- I support this merge, for reasons I gave in the previous thread. Volt-ampere reactive is a specialized unit derived from volt-ampere, which itself is a specialized unit derived from watt. Having a separate article (or stub) for each specialized derived unit either requires an enormous amount of redundant exposition, or leaves non-technically-educated readers without the context needed to understand. --ChetvornoTALK 00:56, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- I think I support it, but I don't agree with your reason. It isn't the unit, but the quantity behind the unit. Well, OK, var is the unit for reactive power, but VA is the unit for volt-amperes. That is, the quantity and unit have the same name. In theory volts measure electromotive force, but everyone just says voltage. Amperage for current isn't common, but not unusual. Many quantities with a unit are commonly named after the unit. Kilos are commonly used for mass. volt-ampere, which itself is a specialized unit derived from watt doesn't seem right, though. Note, for example, that torque and energy both have the same units, but you don't want to get them mixed up. VA is mostly used for sizing transformers, and the wires and such connecting them. The wattage isn't what is important. Gah4 (talk) 03:39, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- Regardless, VAs and VARs are extremely closely related, readers need to understand their relationship to use either, so both can benefit by being explained in the same article. It seems ridiculous to me that WP ever split these two tiny specialized units into separate (inadequate) articles. --ChetvornoTALK 22:17, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- I suppose they should be in the same article, but I don't think they are as closely related, in actual use, as you make it sound. You use VA when sizing transformers. You don't need to know watts, only VA, which you can find adding up all the little plates on the loads you plan to connect. (Most useful for not so variable loads, like a parking lot full of HID lamps.) Now you buy the appropriate transformer. Or, given an already bought transformer, decide what loads to buy. Note also that you don't care at all about var. The power company, on the other hand, wants to keep var low. It requires larger wire and such. So the power company might find it useful to buy devices to reduce var. Now, sometimes power companies will write contracts, quoting a price based on power factor, and so might need to know about var, especially mixed over a variety of loads, like a factory. Gah4 (talk) 22:30, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- Regardless, VAs and VARs are extremely closely related, readers need to understand their relationship to use either, so both can benefit by being explained in the same article. It seems ridiculous to me that WP ever split these two tiny specialized units into separate (inadequate) articles. --ChetvornoTALK 22:17, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- I think I support it, but I don't agree with your reason. It isn't the unit, but the quantity behind the unit. Well, OK, var is the unit for reactive power, but VA is the unit for volt-amperes. That is, the quantity and unit have the same name. In theory volts measure electromotive force, but everyone just says voltage. Amperage for current isn't common, but not unusual. Many quantities with a unit are commonly named after the unit. Kilos are commonly used for mass. volt-ampere, which itself is a specialized unit derived from watt doesn't seem right, though. Note, for example, that torque and energy both have the same units, but you don't want to get them mixed up. VA is mostly used for sizing transformers, and the wires and such connecting them. The wattage isn't what is important. Gah4 (talk) 03:39, 18 May 2020 (UTC)

- Ok, I see where you are coming from, but you are looking at it from the point of view of an electrical engineer. WP is an encyclopedia for general readers. Many, probably most, people coming to this page will not be engineers. For a reader who is not an electrical engineer to understand what volt-ampere reactive is, they need to understand real power, reactive power, apparent power, phase angle, power factor, the units watts, volt amperes, and the power triangle. That's why, as I said in the previous thread, I am in favor of defining all these terms in one article. Failing that, I think any consolidation of these little inadequate stub definitions is a good step. --ChetvornoTALK 00:11, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- I am not sure who is now called an electrical engineer, but for VA, I tend to think about what I would call an electrician. Someone who installs HID light fixtures in factories, for example. All they need to know is how to add up the numbers and make sure that it is low enough for the transformer in use. People who build power plants and power distribution systems, using var, I also wouldn't call electrical engineer, though I am less sure about electrician. But again, they need fairly simple rules, and maybe not know the reason behind the rules. Gah4 (talk) 01:37, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- : Buildings full of people would weep when they find out they aren't practicing electrical engineering and yet they have a keen interest in measurements involving both vars and voltamperes. --Wtshymanski (talk) 01:53, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- Ok, I see where you are coming from, but you are looking at it from the point of view of an electrical engineer. WP is an encyclopedia for general readers. Many, probably most, people coming to this page will not be engineers. For a reader who is not an electrical engineer to understand what volt-ampere reactive is, they need to understand real power, reactive power, apparent power, phase angle, power factor, the units watts, volt amperes, and the power triangle. That's why, as I said in the previous thread, I am in favor of defining all these terms in one article. Failing that, I think any consolidation of these little inadequate stub definitions is a good step. --ChetvornoTALK 00:11, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- @Gah4: "Torque and energy have the same units". Since when? They do not have the same units (though they do have the same dimensions - ML2T-2).

- Torque: Unit - Newton Metre

- Energy: Unit - Joule

- In spite of having the same dimensions, they are not the same thing. It is common place for a shaft to experience a torque with zero energy being transmitted through that shaft (though not vice versa). This occurs if the shaft is stationary. A torque motor is specifically designed to provide torque without providing any mechanical power (and hence energy). 86.164.109.84 (talk) 13:15, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- Yes. VA and watts have the same dimensions, but they are not the same unit. Potential energy of a rock on a hill might be described in terms of gravitational force and height. If you are in a country where the Joule is a common energy unit, then all is well. In the US, though, the foot pound is an energy unit, and also a torque unit. BTU is used for thermal energy, but not usually for mechanical energy. The Horsepower-hour might be used for mechanical energy. Gah4 (talk) 17:58, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- The big error here is that the pound is not a unit of force. It is a unit of mass. The point is usually fudged by referring to the 'pound-force' as in the downward force exerted by a mass of one pound. It is unofficially defined as the gravitational force exerted on a mass of one avoirdupois pound on the surface of Earth. Thus it is not a constant over the planet's surface and cannot be used for anything other than measurements where an error of around ±1% can be tolerated.

- The unit of force is the poundal, defined as that force required to accelerate a mass of one pound at one foot per second squared. Although attempts have been made to define the pound-force more precisely, the poundal is preferred. 86.164.109.84 (talk) 12:53, 20 May 2020 (UTC)

- Pound force is defined in terms of a standard g, such that the unit doesn't change as you move around, though the difficulty of calibration might. Yes it is mostly useful when 1% is good enough. Actually, though, I think it is better than that. It is, for example, used as the unit for jet (and rocket) engine thrust, where a mass unit is completely wrong. I know a museum with a jet engine exhibit, with the thrust given in pounds and kg, as someone didn't figure out that pounds were force. It seems that there is an official Smithsonian document that says pounds and newtons, but someone forgot to read it. Poundal is completely different, as far as I know only used for ChE. Any physics done in English units uses the foot-slug-second system, with pound as the unit of force. Gah4 (talk) 17:42, 20 May 2020 (UTC)

- In the past, I have done lots of calculations using poundals. Enough to convince anyone of the superiority of the SI system.

- The thrust of jet (and rocket) engines is indeed expressed in pounds and kilogrammes. In this specific case the kilogramme (thrust) is precisely defined. One kilogramme of thrust is equal to 9.8206 Newtons exactly. This makes the pound (thrust) equal to 4.45454+ Newtons. The kilogramme (thrust) is not the same as the (unofficial for SI purposes) definition of the kilogramme (force), the difference being that it is slightly over 1% larger. Correspondingly, the pound (thrust) though nowadays defined in terms of the kilogramme (thrust) is not the same as any definition of pound (force).

- Specifying engine thrust in kilogrammes or pounds is a more useful measure when trying to work out the lift that the engine(s) generate via the wings and how effectively this would overcome the weight of the aeroplane taking into account drag etc. Using a slightly larger definition for kilogramme (thrust) gives a margin of error as measuring it is not that exact. The De Haviland Comet was famous for only having the lower half of the fuselage painted, the upper being bare polished aluminium. Regardless of how impressive everyone thought it looked, the reality was the weight of the extra paint would mean that the aircraft's fully loaded weight would exceed the available lift and it would not unstick. 86.164.109.84 (talk) 12:36, 21 May 2020 (UTC)

- I don't know about other places, but it is supposed to be pounds and newtons for museums. That was told to me by the person at the museum that had it in kg. And for propeller airplanes, I might not have guessed, in HP and kW. Another interesting unit for rockets and jets is specific impulse, which is commonly thrust divided by propellant (fuel for jets) weight flow rate. That is, not mass, but mass times g. The result, then, is the same in metric and English units. Gah4 (talk) 13:53, 21 May 2020 (UTC)

- Pound force is defined in terms of a standard g, such that the unit doesn't change as you move around, though the difficulty of calibration might. Yes it is mostly useful when 1% is good enough. Actually, though, I think it is better than that. It is, for example, used as the unit for jet (and rocket) engine thrust, where a mass unit is completely wrong. I know a museum with a jet engine exhibit, with the thrust given in pounds and kg, as someone didn't figure out that pounds were force. It seems that there is an official Smithsonian document that says pounds and newtons, but someone forgot to read it. Poundal is completely different, as far as I know only used for ChE. Any physics done in English units uses the foot-slug-second system, with pound as the unit of force. Gah4 (talk) 17:42, 20 May 2020 (UTC)

- Yes. VA and watts have the same dimensions, but they are not the same unit. Potential energy of a rock on a hill might be described in terms of gravitational force and height. If you are in a country where the Joule is a common energy unit, then all is well. In the US, though, the foot pound is an energy unit, and also a torque unit. BTU is used for thermal energy, but not usually for mechanical energy. The Horsepower-hour might be used for mechanical energy. Gah4 (talk) 17:58, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

- In spite of having the same dimensions, they are not the same thing. It is common place for a shaft to experience a torque with zero energy being transmitted through that shaft (though not vice versa). This occurs if the shaft is stationary. A torque motor is specifically designed to provide torque without providing any mechanical power (and hence energy). 86.164.109.84 (talk) 13:15, 19 May 2020 (UTC)

What has museum got to do with rating the output of aeroplane engines? Specific impulse has little to do with the actual thrust but is more a measure of the efficiency (more connected with the amount of fuel that you need to carry to achieve a particular thrust over a period of time, bearing in mind the necessity of carrying fuel to transport the fuel (and carrying fuel to transport that fuel etc. etc.). And, of course, not forgetting the mass of the tanks required to hold that fuel. It's a complicated issue.

This latter is why aeroplanes make fuel stops when travelling long distances. Although half way around the world has always been possible, it has historically been more cost efficient to make fuel stops as the fuel consumed landing, taxying, and taking off again (not forgetting landing and take off fees plus refuelling fees) has been less than the fuel to carry the fuel. However: engine efficiency has improved to the point where half way around the globe is now cost effective, once the extra fees are deducted.

It is the reason that rockets that launch space craft are so large. Virtually all of the rocket is fuel tanks to carry the fuel required to lift the fuel (refuelling stops part way not being an option at present) not to mention fuel to lift the fuel tanks. Only a very small fraction of the fuel carried actually gets the payload into orbit. 86.164.109.84 (talk) 15:59, 22 May 2020 (UTC)

- I have only looked into what museums do for exhibits. It might be that aeronautical engineers have their own special units. Specific impulse is an interesting case, though. If you multiply by g, you get a velocity. For rockets, this is related to exhaust velocity. For jets, since it includes fuel but not air, it isn't very related to exhaust velocity. For any unit that is a combination of length and time, you can multiply by the appropriate power of g, to leave only time dimensions. That will make it the same for metric and non-metric units. Gah4 (talk) 22:30, 22 May 2020 (UTC)