Zaju chuishao fu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

| Zaju chuishao fu | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

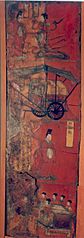

Female figures dressed in the Zaju chuishao fu along with cross hairstyle and golden headpiece, early Northern Wei period: guichang (left) and guipao (middle and right) | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 雜裾垂髾服 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 杂裾垂髾服 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Guiyi | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 袿衣 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Zaju chuishao fu (traditional Chinese: 雜裾垂髾服; simplified Chinese: 杂裾垂髾服; pinyin: zájū chuíshāo fú), also called Guiyi (Chinese: 袿衣),[1] and sometimes referred as "Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing" or "swallow tail" clothing for short in English,[2]: 62–64 [3] is a form of set of attire in hanfu which was worn by Chinese women. The zaju chuishao fu can be traced back to the pre-Han period and appears to have originated the sandi (Chinese: 三翟) of the Zhou dynasty;[4] it then became popular during the Han,[4] Cao Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern dynasties.[5] It was a common form of aristocratic costumes in the Han and Wei dynasties[4] and was also a style of formal attire for elite women.[3] The zaju chuishao fu can be further divided into two categories of clothing style based on its cut and construction: the guipao, and the guichang (or guishu).[1][4]

The guipao falls in the category of paofu (long robe);[1][4] however, some Chinese scholars also classify it as being a type of shenyi.[6]: 62 On the other hand, the guichang follows yichang (or ruqun) system consisting of a ru, an upper garment, and a qun, a long skirt.[1][4]

The zaju chuishao fu was multi-layered and was decorated with an apron-like decorative cloth at the waist with triangular-strips at the bottom and with pieces of ribbons worn underneath the apron which would hung down from the waist.[3] The popularity of ribbons later fell and the decorative hems were eventually enlarged.[3]

This form of attire also spread to Goguryeo, where it is depicted in the tomb murals found in the Anak Tomb No.3.

Terminology[edit]

The Chinese character gui《袿》in the term guiyi (袿衣) refers to the shape of its hanging part which is broad at the top region but becomes narrow at the bottom making it look like a daogui, an ancient measuring tool for Chinese medicine, in appearance.[2]: 38

History[edit]

The term guiyi was recorded prior to the Han dynasty in the Ode to Goddess written by Song Yu, a Chinese poet from the late Warring States Period, which demonstrates that the zaju chuishao fu originated earlier than the Han dynasty.[4] The guipao, which is a form of paofu in the broad sense, appears to have originated from one of the Queen's ceremonial clothing dating from the Zhou dynasty called sandi (Chinese: 三翟).[1][4] According to some Chinese scholars, the attire called guiyi in the Han dynasty was in the style of the quju shenyi.[2]: 38 However, according In the Han and Wei period, the guipao was one of the common aristocratic costumes.[4]

Han dynasty[edit]

The type of guiyi, which was worn in the Han dynasty, was in the form of a guipao.[1][4] In the Han dynasty, the silk decorations were cut into the shapes of arch; these originated from the sandi recorded in the Rites of Zhou.[4] The guipao was popular in the Han dynasty, but its popularity started to fade in the late Eastern Han dynasty.[4] The guiyi which follows the ruqun system also appeared in the Han dynasty, where it was called guichang or guishu.[4]

Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties[edit]

On the whole, the costumes of the Wei and Jin period still followed the patterns of Qin and Han dynasties. However, the clothing of women in this period were generally large and loose. The carefree lifestyle brought about the development of women's garments in the direction of extravagant and ornate beauty.[7][5] This carefree lifestyle, which was reflected in the garment and apparel of the people living in this period, can be explained by the historical circumstances which impacted the mood of the people: during the Northern and Southern dynasties was a period of volatility, the barbarians invaded Central Plain, thus, various wars and battles occurred. The once dominant laws and orders collapsed, so did the once unchallenged power of Confucianism.[5] At the meantime, the philosophy of Laozi and Zhuangzi became popular. Buddhist scriptures were translated, Taoism was developed, and Humanitarian ideology emerged among the aristocrats.[5] However, all these posed a threat to the conservative and imperial power, which tried to crush them by force. These policies forced these scholars to seek comfort and relief in life.[7] They were interested in various kinds of philosophy and studied a lot of the "mysterious learning". They preferred a life of truth and freedom. They dressed themselves in free and casual elegance.

The zaju chuishao fu (or guiyi), which was worn in the Wei, Jin, Northern, and Southern dynasties, was quite different from the style worn in the Han dynasty.[6]: 62 [2]: 62–64 It had evolved from the one-piece long robe, either from the paofu[5] or the shenyi[6]: 62 worn in the Han dynasty, and had wide sleeves.[5]

The guiyi are depicted with in the paintings of Gu Kaizhi.[5][1] The guichang eventually became more popular than the guipao during this period as the set of attire ruqun itself had become more popular.[1][4]

The guiyi also evolved in terms of shape in the Northern and Southern dynasties when the long ribbons were no longer seen and the swallow-tailed corner became bigger; as a result the flying ribbons and the swallow-tailed corners were combined into one.[2]: 62–64 These changes can be found in the paintings Wise and Benevolent Women and Nymph of the Luo River by Gu Kaizhi, as well as the lacquered paintings unearthed from the Sima Jinlong tomb in Datong and the Goguryeo tomb murals from the Anak Tomb No. 3.[2]: 62–64 [6]: 62

Construction and Formation[edit]

Typically the guiyi was decorated with "xian" (襳) and "shao" (髾).[2]: 62–64 The Shao refers to pieces of silk cloth sewn onto the lower hem of the dress, which were wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, so that triangles were formed overlapping each other.[2]: 62–64 "Xian" refers to some relatively long, silk ribbons which extended from the short-cut skirt.[8][5] While the wearer was walking, these lengthy ribbons made the sharp corners and the lower hem wave like a flying swallow, hence the Chinese phrase "beautiful ribbons and flying swallowtail" (華帶飛髾).[2]: 62–64 There are also two types of guiyi. The guiyi which follows the 'one-piece system' is called guipao while the other form of guiyi, guichang (or guishu), follows the 'separate system', consisting of ruqun which is a set of attire composed of a ru, an upper garment, and a qun as a long skirt.[4]

The change in the shape and structure of the guiyi reflects the historical trend of the fading popularity of guipao in the late Eastern Han and the increase popularity of the guichang (or guishu) which eventually became the mainstream style in the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern dynasties.[4]

In the guichang, the upper garment was opened at the front and was tied at the waist. The sleeves were broad and fringed at the cuffs with decorative borders of a different colour. The skirt had spaced coloured stripes and was tied with a white silk band at the waist. There was also an apron between the upper garment and skirt for the purpose of fastening the waist. Apart from wearing a multi-coloured skirt, women also wore other kinds such as the crimson gauze-covered skirt, the red-blue striped gauze double skirt, and the barrel-shaped red gauze skirt. Many of these styles are mentioned in historical records.[8] Wide sleeves and long robes, flying ribbons and floating skirts, elegant and majestic hair ornaments,[7] all these became the fashion style of Wei and Jin female appearance.

During the Northern and Southern dynasties, the guiyi underwent further changes in style.[2]: 62–64 The long flying ribbons were no longer seen and the swallow-tailed corners became enlarged; as a result, the flying ribbons and swallow-tailed corners were combined into one.[9][2]: 62–64

Influences and derivatives[edit]

Goguryeo[edit]

Depictions of women wearing guiyi can also be found in Goguryeo tomb murals, as found in the Anak Tomb No.3.[2] The wife of the tomb owner of Anak Tomb No.3 dresses in Chinese guiyi,[2][10] which may indicate the clothing style worn in the Six dynasties.[11] The tomb belongs to a male refugee called Dong Shou (died in 357 AD) who fled from Liaotong to Goguryeo according to Chinese scholar Yeh Pai, a conclusion which is also accepted in the formal Korean report issued in 1958 although some Korean scholars believe the tomb to belong to King Mi-chon.[12]

Gallery[edit]

-

Mogao fresco of a woman dressing in Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing, Western Wei dynasty (535–557)

-

Virtuous women of ancient Cathay (China), lacquer painting

-

Women dressing in Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing, a lacquer painting over a four-panel wooden folding screen, 5th century

-

Consort Ban and Emperor Cheng of Han, Consort Pan wearing a Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing

-

Female figures dressing in Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing, 5th century

-

The virtuous women in Cathayan (Chinese) history, 5th century

-

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Nymph of the Lo River (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Nymph of the Lo River (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Nymph of the Lo River (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Nymph of the Lo River (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Nymph of the Lo River (detail) by Gu Kaizhi

-

Modern pictorial reconstruction of Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing as in Admonitions of the Court Instructress and Nymph of the Lo River

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h 周方; 服装·艺术设计学院, 东华大学; 周方; 卞向阳; 服装·艺术设计学院,上海200051, 东华大学 (2018-07-02). "罗袿徐转红袖扬 ——关于古代袿衣的几个问题 [Abstract]". 丝绸 (2018年 06). ISSN 1001-7003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Xun Zhou, Chunming Gao, 周汛, Shanghai Shi xi qu xue xiao. Zhongguo fu zhuang shi yan jiu zu. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. 1987. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Howard, Michael C. (2016). Textiles and clothing of Viet Nam : a history. Jefferson, North Carolina. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4766-6332-6. OCLC 933520702.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bian, Xiang Yang; Zhou, Fang (2018). "A Study on the Origin and Evolution of Shape and Structure of 'Gui-Yi' in Ancient China". Researchgate.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hua, Mei; 华梅 (2004). Chinese clothing. 于红. Beijing: China International Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 7-5085-0612-X. OCLC 61214922.

- ^ a b c d Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming; Zhou, Zuyi; Jin, Baoyuan. Zhongguo fu shi wu qian nian 中國服飾五千年 [5000 years of Chinese costumes] (in Chinese). 上海市戲曲學校中國服裝史硏究組編著. Hongkong: Shang wu yin shu guan Xianggang fen guan [商務印書館香港分館 學林出版社]. OCLC 973669827.

- ^ a b c "The elegant Wei and Jin Period".

- ^ a b Duong, Nancy (2013). "Evolution of Chinese Clothing and Cheongsam".

- ^ "Evolution of Chinese Clothing and Cheongsam/Qipao". 2013.

- ^ a b Chung, Young Yang (2005). Silken threads : a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. New York: H.N. Abrams. p. 294. ISBN 0-8109-4330-1. OCLC 55019211.

- ^ Lee, Junghee. "The Evolution of Koguryo Tomb Murals". eng.buddhapia.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Japan. John Whitney Hall, 耕造. 山村. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1988–1999. p. 300. ISBN 0-521-22352-0. OCLC 17483588.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)