Suffolk, Virginia

Suffolk, Virginia | |

|---|---|

A view of North Main Street in downtown Suffolk | |

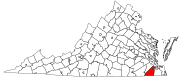

Location in the Commonwealth of Virginia. | |

| Coordinates: 36°44′28″N 76°36′35″W / 36.74111°N 76.60972°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | None (Independent city) |

| Founded | 1742 |

| Area | |

| • Independent city | 428.91 sq mi (1,110.86 km2) |

| • Land | 399.16 sq mi (1,033.82 km2) |

| • Water | 29.75 sq mi (77.05 km2) |

| Elevation | 39 ft (12 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Independent city | 94,324 |

| • Density | 220/sq mi (85/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,799,674 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 23432-23439 |

| Area code(s) | 757, 948 |

| FIPS code | 51-76432[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1500187[3] |

| Website | http://www.suffolkva.us/ |

Suffolk is an independent city in Virginia, United States. As of 2020, the population was 94,324.[4] It is the 10th-most populous city in Virginia, the largest city in Virginia by boundary land area as well as the 14th-largest in the country.[5] Suffolk is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. This also includes the independent cities of Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach, and smaller cities, counties, and towns of Hampton Roads. With miles of waterfront property on the Nansemond and James rivers, present-day Suffolk was formed in 1974 after consolidating with Nansemond County and the towns of Holland and Whaleyville. The current mayor (as of 2021) is Mike Duman.[6]

History[edit]

Prior to colonization, the region was inhabited by the indigenous Nansemond people. The settlement of Suffolk was established in 1742 by Virginian colonists as a port town on the Nansemond River. It was originally named Constant's Warehouse (for John Constant, one of the first founders of the settlement) before being renamed after Royal Governor of Virginia Sir William Gooch's home county of the same name in England. During the colonial era, Virginian colonists in the region cultivated tobacco with enslaved labor as a cash crop, before transitioning to mixed farming. Suffolk was designated as the county seat of Nansemond County in 1750.

Early in its history, Suffolk became a land transportation gateway to the areas east of it in South Hampton Roads. Before the American Civil War, both the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad and the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad were built through Suffolk, early predecessors of 21st-century Class 1 railroads operated by CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern, respectively. Other railroads and later major highways followed after the war.

Suffolk became an incorporated town in 1808. Suffolk became a stop on the Atlantic and Danville Railway in 1890.[7] In 1910, it incorporated as a city and separated from Nansemond County. However, it remained the seat of Nansemond County until 1972, when its former county became the independent city of Nansemond. In 1974, the independent cities of Suffolk and Nansemond merged under Suffolk's name and charter.

Peanuts grown in the surrounding areas became a major agricultural industry for Suffolk. Notably, Planters' Peanuts was established in Suffolk beginning in 1912. Suffolk was the 'birthplace' of Mr. Peanut, the mascot of Planters' Peanuts. For many years, the call-letters of local AM radio station WLPM stood for World's Largest Peanut Market. (WLPM's license was cancelled in 1996 [8])

Geography[edit]

Suffolk is located at 36°44′29″N 76°36′36″W / 36.741347°N 76.609881°W (36.741347, −76.609881).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 429 square miles (1,110 km2), of which 400 square miles (1,000 km2) is land and 29 square miles (75 km2) (6.7%) is water.[9] It is the largest city in Virginia by land area and second largest by total area. Part of the Great Dismal Swamp is located in Suffolk.

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 1,395 | — | |

| 1870 | 930 | −33.3% | |

| 1880 | 1,963 | 111.1% | |

| 1890 | 3,354 | 70.9% | |

| 1900 | 3,827 | 14.1% | |

| 1910 | 7,008 | 83.1% | |

| 1920 | 9,123 | 30.2% | |

| 1930 | 10,271 | 12.6% | |

| 1940 | 11,343 | 10.4% | |

| 1950 | 12,339 | 8.8% | |

| 1960 | 12,609 | 2.2% | |

| 1970 | 9,858 | −21.8% | |

| 1980 | 47,621 | 383.1% | |

| 1990 | 52,141 | 9.5% | |

| 2000 | 63,677 | 22.1% | |

| 2010 | 84,585 | 32.8% | |

| 2020 | 94,324 | 11.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] 2010-2020[14] | |||

2020 census[edit]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[15] | Pop 2010[16] | Pop 2020[14] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 33,940 | 43,034 | 43,837 | 53.30% | 50.88% | 46.47% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 27,524 | 35,771 | 39,194 | 43.22% | 42.29% | 41.55% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 185 | 232 | 255 | 0.29% | 0.27% | 0.27% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 487 | 1,324 | 1,672 | 0.76% | 1.57% | 1.77% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 15 | 50 | 68 | 0.02% | 0.06% | 0.07% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 64 | 109 | 543 | 0.10% | 0.13% | 0.58% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 653 | 1,650 | 4,503 | 1.03% | 1.95% | 4.77% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 809 | 2,415 | 4,252 | 1.27% | 2.86% | 4.51% |

| Total | 63,677 | 84,585 | 94,324 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 Census[edit]

As of the census[17] of 2010, there were 84,585 people, 23,283 households, and 17,718 families residing in the city. The population density was 159.2 inhabitants per square mile (61.5/km2). There were 24,704 housing units at an average density of 61.8 per square mile (23.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 50.1% White, 42.7% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.6% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 2.3% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 2.9% of the population.

There were 23,283 households, out of which 36.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.1% were married couples living together, 16.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.9% were non-families. 20.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.09.

The age distribution was 27.8% under the age of 18, 7.1% from 18 to 24, 31.1% from 25 to 44, 22.5% from 45 to 64, and 11.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.4 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 87.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $41,115, and the median income for a family was $47,342. Males had a median income of $35,852 versus $23,777 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,836. About 10.8% of families and 13.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.2% of those under age 18 and 11.2% of those age 65 or over.

As of 2005, the city's median income jumped to $60,484. A number of government-related, contractor high-tech jobs had developed with new businesses in the city's northern corridor, bringing in wealthier residents. Suffolk ranked a close second in median income to its neighbor Chesapeake in South Hampton Roads.[18]

Adjacent counties and cities[edit]

- Norfolk

- Portsmouth

- Chesapeake

- Newport News (water boundary)

- Isle of Wight County

- Southampton County

- Camden County, North Carolina

- Gates County, North Carolina

National protected areas[edit]

2008 tornado[edit]

The city was hit by an EF3 tornado which produced a large swath of extensive damage through the city and nearby communities during the late afternoon of April 28, 2008.[19] After 4:00 PM EDT on April 28, a tornado touched down multiple times, causing damage and leaving more than 200 injured in Suffolk. the path of the storm passed north and west of the downtown area, striking near Sentara Obici Hospital and in the unincorporated town of Driver. The storm seriously damaged more than 120 homes and 12 businesses. The subdivisions of Burnett's Mill and Hillpoint Farms were severely damaged, as were several older historic structures in Driver. Near Driver, the large radio and television broadcast towers, which were located in an antenna farm serving most of Hampton Roads, were spared serious damage.

Governor Tim Kaine declared a state of emergency and directed state agencies to assist the recovery and cleanup efforts. Police officers and firefighters from across Hampton Roads were sent to Suffolk to help in a quarantine and cleanup of the damaged areas. On May 1, the state estimated property damages at $20 million.

Education[edit]

Suffolk Public Schools, the local public school system, operates 12 elementary schools, four middle schools, three high schools, and one alternative school. Nansemond-Suffolk Academy is a private college preparatory school located on Pruden Blvd.

Paul D. Camp Community College has a campus in Suffolk.

Transportation[edit]

Suffolk's early growth depended on its waterfront location, with access to the waterways for power and transportation. Subsequent transportation infrastructure upgraded its connections with other markets. These continue to be major factors in the 21st century.

Bike trails[edit]

The Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge includes dozens of miles of trails accessible via White Marsh Road at Washington Ditch and other entry sites. Additional bike trails can be found at Lone Star Lakes City Park off Godwin Blvd. This city park provides over 4 miles (6.4 km) of rock trails. There are many rural roads with light traffic available for road riding. Adjacent to Suffolk is Isle of Wight County, where a county facility called Nike Park includes a bike trail approximately 21⁄2 miles in a loop.

Waterways[edit]

Suffolk was initially a port at the head of navigation of the Nansemond River. The Nansemond flows into the James River near its mouth and the ice-free harbor of Hampton Roads.

Railroads[edit]

The two railroads completed through Suffolk before the American Civil War were later joined by four more. These were eventually consolidated during the modern merger era of North American railroads which began around 1960. Suffolk was served by several passenger lines, concluding with Amtrak's Mountaineer, which ended in 1977. At least two former passenger stations are still standing, the Seaboard Coast Line station, now the Seaboard Station Railroad Museum, and the Norfolk and Western Railway station at 100 Hollady Street. The N&W station was used by Amtrak (as "Holiday Street"[20]) until 1977 when the Mountaineer was replaced by a bus connection to the Hilltopper.[21] Currently, Amtrak's Northeast Regional between Norfolk and Petersburg passes by the N&W station without stopping.

Today, Suffolk is served by three freight railroads. It is located on a potential branch line for the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor between Petersburg, Virginia and South Hampton Roads, being studied by the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation.

Highways[edit]

Suffolk is served by U.S. Highways 17, 13, 58, 258, and 460. Interstate 664, part of the Hampton Roads Beltway, crosses through the northeastern edge of the city. State Route 10 is also a major highway in the area.

In 2006, Suffolk assumed control of its road system from the Virginia Department of Transportation, which is customary among Virginia's independent cities. Since the Byrd Road Act of 1932 created Virginia's Secondary Roads System, the state maintains the roads in most counties and towns. An exception was made by the General Assembly when the former Nansemond County became an independent city and consolidated Suffolk in the 1970s. The state maintained the primary and secondary routes in Suffolk until July 1, 2006.

Bridges, bridge-tunnel[edit]

The Monitor–Merrimac Memorial Bridge–Tunnel connects Suffolk to the independent city of Newport News on the Virginia Peninsula from South Hampton Roads. It is part of the Hampton Roads Beltway, a circumferential interstate highway that links the seven largest cities of Hampton Roads. Completed in 1992, it provided a third major vehicle crossing of the Hampton Roads harbor area and cost $400 million to build.

The city and VDOT have had disputes over ownership and responsibility for the Kings Highway Bridge (circa 1928) across the Nansemond River on State Route 125. VDOT closed it in 2005 for safety reasons.[22][23]

About 3,300 motorists a day used the bridge that connected Chuckatuck and Driver. The closure forced detours of as much as 19 miles (31 km). The cost of a new bridge for the King's Highway crossing is estimated at $48 million, far more than could be recovered through collection of tolls at that location.[24] In 2007, VDOT announced that it would contract for demolition and removal of the bridge. According to newspaper accounts, this was the first time in VDOT's history that it did not plan for a replacement facility.[25]

Virginia is reviewing proposals under a public-private partnership for a major realignment and upgrade of U.S. 460 from Suffolk west to Interstate 295 near Petersburg. In 1995, the Virginia General Assembly passed the Public-Private Transportation Act, allowing private entities to propose innovative solutions for designing, constructing, financing, and operating transportation improvements. The new roadway would be funded through collection of tolls.

As part of the Suffolk 2026 Comprehensive Plan, the city plans to bypass the crossroads community of Whaleyville in southwestern Suffolk City. US 13 (along with NC Highway 11) is a strategic highway corridor in North Carolina toward Greenville.[26][27]

Public transportation[edit]

The City of Suffolk operates Suffolk Transit, which provides local bus service.[28]

Economy[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

In modern times, Suffolk remains a major peanut processing center and railroad and highway transportation hub. It hosts a diverse combination of industrial, manufacturing, distribution, retail, and hospitality businesses, as well as active farming.

In 2002, the new Louise Obici Memorial Hospital was completed and dedicated. It was acquired in 2005 by the Sentara Health System. Planters' Peanuts has been a major employer, now owned by Kraft Foods. Each fall since 1977, the City of Suffolk hosts Suffolk Festivals Incorporated's annual Peanut Fest.

Other large employers in the City of Suffolk include Unilever, Lipton Tea, Massimo Zanetti Beverage Group, Wal-Mart, Target, QVC, and two major modeling and simulation companies, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon. Lockheed Martin built its "Center for Innovation" around a lighthouse in Suffolk, for which the campus is called 'The Lighthouse'. Raytheon won a DoD contract to manufacture 'Miniature Air-Launched Decoy Jammers'(MALD-J), which it has been producing with Cobham Composite Products: 202 vehicles for a price of $81 million.[29]

The U.S. Joint Forces Command (JFCOM) facility, near the intersection of US 17 and Interstate 664, has resulted in a growth in defense contracting and high-tech jobs since 1999. Through the following decade, JFCOM employed a growing number of defense contractors until it reached over 3,000. [citation needed] By September 2010, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates recommended to decommission JFCOM, as a matter of reallocating and rebalancing the U.S. Department of Defense budget, to better address changing needs and fiscal demands.

The announcement led to speculation about the effects the loss of JFCOM would have on the Hampton Roads economy in general and (more specifically), on the future of related businesses located in the Harborview section of Suffolk. In August 2011 JFCOM was disestablished. But many critical JFCOM functions, such as joint training, joint exercises, and joint development were retained in the buildings vacated by JFCOM, under the auspices of the Joint Staff J7 Directorate, referred to as either "Pentagon South"[29] or "Joint and Coalition Warfighting".

By summer 2013, city officials expected the Naval Network Warfare Command, NNWC Global Network Operations Center Detachment, Navy Cyber Defense Operations Command and Navy Cyber Forces to occupy buildings vacated by JFCOM. These commands have been considered a boon to north Suffolk, bringing an estimated 1,000 additional employees, counting military, civilians and contractors, with an estimated annual payroll of $88.9 million.[29] The buildup in these defense functions resulted in Suffolk's median income increasing markedly in this period.

Media[edit]

Suffolk's daily newspapers are the local Suffolk News-Herald, the Virginian-Pilot from Norfolk and the Daily Press of Newport News. Other papers include the New Journal and Guide, and Inside Business.[30] Coastal Virginia Magazine serves as a bi-monthly regional magazine for Suffolk and the Hampton Roads area.[31] Hampton Roads Times serves as an online magazine for all the Hampton Roads cities and counties. Suffolk is served by a variety of radio stations on the AM and FM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area.[32]

Suffolk is also served by several television stations. The Hampton Roads designated market area (DMA) is the 42nd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[33] The major network television affiliates are WTKR-TV 3 (CBS), WAVY 10 (NBC), WVEC-TV 13 (ABC), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (FOX), and WPXV 49 (ION Television). The Public Broadcasting Service station is WHRO-TV 15. Suffolk residents also can receive independent stations, such as WSKY broadcasting on channel 4 from the Outer Banks of North Carolina and WGBS-LD broadcasting on channel 11 from Hampton. Suffolk is served by Charter Communications.[34] The City of Suffolk Media & Community Relations Department operates Municipal Channel 8 on the local Charter Cable television system. Programming includes television coverage of many City activities and events, including live Government-access television (GATV) broadcasts of all regular City Council meetings, and special features including "On The Scene", "Suffolk Seniorcize", and "Suffolk Business Today". DirecTV and Dish Network are also popular as an alternative to cable television in Suffolk.

Boroughs[edit]

Suffolk is divided politically into seven boroughs,[35] one corresponding to the former city of Suffolk and one corresponding to each of the six magisterial districts of the former Nansemond County.[36] The boroughs are Chuckatuck,[37] Cypress,[38] Holy Neck,[39] Nansemond,[40] Sleepy Hole,[41] Suffolk,[42] and Whaleyville.[43]

Sister cities[edit]

In 1981, the county of Suffolk in England became Suffolk's first sister city as a result of the personal interest in the Sister Cities concept by Virginia's Governor, Mills E. Godwin. A native of the city, Governor Godwin believed that Sister Cities would benefit the community culturally and educationally. Suffolk's second sister city relationship with Oderzo, Italy, began in 1995 because of one man, Amedeo Obici. Mr. Obici was a native of Oderzo and the founder of Planters Nut and Chocolate Company in Suffolk.

Suffolk Sister Cities International, Inc. (SSCI) is a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit established to promote international relationships as directed by Suffolk City Council through its appointed Suffolk Sister Cities Commission. Its membership is open to all who are interested in fostering the goals of the organization.

SSCI and its international youth association, SIYA, have won national awards for Youth and Education and for the Best Overall Program for cities with populations less than 100,000.[44]

Notable people[edit]

- James Avery (1945–2013), actor who portrayed the father on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air was from Pughsville, Virginia, much of which is now located in Suffolk

- Johnnie Barnes, former NFL player

- Darius Bea, Negro league outfielder and pitcher[45]

- Jessie Britt, former NFL player

- Rose Marie Brown (1919-2015), Broadway performer, Miss Virginia and fourth runner-up Miss America 1939

- Charlie Byrd, guitarist

- Judith Godwin, abstract expressionist artist

- Mills E. Godwin Jr., Virginia governor

- Phyllis Gordon (1889-1964), actress, born in Suffolk

- Ryan Speedo Green, bass-baritone opera singer

- D. Arthur Kelsey, Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia

- Joe Kenda, retired homicide detective

- Lex Luger (musician), musician

- Joe Maphis, country music guitarist

- Jeff W. Mathis III, U.S. Army major general

- Amedeo Obici, founder of Planters' Peanuts

- Lewis F. Powell Jr. (1907-1998), US Supreme Court Justice 1972-1987

- Sugar Rodgers, (WNBA) Basketball player for the Las Vegas Aces

- M. Virginia Rosenbaum, surveyor and newspaper editor

- Hope Spivey, gymnast, participated in 1988 Olympics in Seoul

- Deatrich Wise Jr., football player for New England Patriots

- Shane Dollar, hip hop artist

Attractions[edit]

Suffolk's boundaries include many rural areas and towns, as well central Suffolk itself. For historic districts throughout Suffolk, see National Register of Historic Places listings in Suffolk, Virginia.

- Driver Historic District

- Great Dismal Swamp

- Nansemond County Training School

- Phoenix Bank of Nansemond

- Riddick's Folly

- St. John's Church, Chuckatuck

- Suffolk Center for Cultural Arts

- Suffolk Historic District

- The Seaboard Station Railroad Museum, located at 326 North Main Street, is housed in a historic Seaboard Coast Line station. The museum features a model train layout depicting Suffolk, and railroad memorabilia. Admission is free, with donations accepted, and open year-round. A few blocks away from the railroad museum is the former Norfolk and Western Railway and Amtrak station at 100 Holladay Street.

-

Driver Historic District

-

Great Dismal Swamp

-

Phoenix Bank of Nansemond

-

St. John's Chuckatuck

Climate[edit]

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Suffolk has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[46]

| Climate data for Suffolk, Virginia (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1945–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

88 (31) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49.3 (9.6) |

52.4 (11.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

69.2 (20.7) |

76.1 (24.5) |

83.4 (28.6) |

86.8 (30.4) |

85.1 (29.5) |

79.6 (26.4) |

70.5 (21.4) |

60.5 (15.8) |

52.7 (11.5) |

68.8 (20.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 40.2 (4.6) |

42.7 (5.9) |

49.1 (9.5) |

58.6 (14.8) |

66.4 (19.1) |

74.2 (23.4) |

78.3 (25.7) |

76.8 (24.9) |

71.3 (21.8) |

61.0 (16.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

43.7 (6.5) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 31.1 (−0.5) |

32.9 (0.5) |

38.9 (3.8) |

48.0 (8.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

65.1 (18.4) |

69.7 (20.9) |

68.6 (20.3) |

63.0 (17.2) |

51.5 (10.8) |

40.8 (4.9) |

34.8 (1.6) |

50.1 (10.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

4 (−16) |

14 (−10) |

24 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

49 (9) |

46 (8) |

39 (4) |

23 (−5) |

18 (−8) |

4 (−16) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.66 (93) |

2.96 (75) |

4.07 (103) |

3.62 (92) |

3.95 (100) |

4.70 (119) |

5.69 (145) |

5.77 (147) |

5.80 (147) |

4.26 (108) |

3.65 (93) |

3.69 (94) |

51.82 (1,316) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.1 (7.9) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

5.8 (15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.7 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 123.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.6 |

| Source: NOAA[47][48] | |||||||||||||

Politics[edit]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 20,082 | 40.45% | 28,676 | 57.77% | 884 | 1.78% |

| 2016 | 18,006 | 41.64% | 23,280 | 53.84% | 1,954 | 4.52% |

| 2012 | 17,820 | 41.86% | 24,267 | 57.01% | 479 | 1.13% |

| 2008 | 17,165 | 43.01% | 22,446 | 56.24% | 297 | 0.74% |

| 2004 | 16,763 | 52.08% | 15,233 | 47.32% | 193 | 0.60% |

| 2000 | 11,836 | 47.99% | 12,471 | 50.57% | 354 | 1.44% |

| 1996 | 8,572 | 41.30% | 10,827 | 52.17% | 1,355 | 6.53% |

| 1992 | 8,697 | 43.01% | 9,196 | 45.47% | 2,330 | 11.52% |

| 1988 | 9,742 | 54.27% | 8,080 | 45.01% | 128 | 0.71% |

| 1984 | 10,128 | 52.97% | 8,842 | 46.25% | 149 | 0.78% |

| 1980 | 7,179 | 42.82% | 9,064 | 54.07% | 522 | 3.11% |

| 1976 | 6,066 | 38.86% | 9,246 | 59.24% | 297 | 1.90% |

| 1972 | 2,137 | 69.54% | 898 | 29.22% | 38 | 1.24% |

| 1968 | 1,277 | 37.95% | 1,044 | 31.03% | 1,044 | 31.03% |

| 1964 | 1,463 | 48.06% | 1,579 | 51.87% | 2 | 0.07% |

| 1960 | 1,406 | 49.61% | 1,419 | 50.07% | 9 | 0.32% |

| 1956 | 1,617 | 57.50% | 1,103 | 39.22% | 92 | 3.27% |

| 1952 | 1,622 | 57.17% | 1,209 | 42.62% | 6 | 0.21% |

| 1948 | 741 | 35.80% | 1,030 | 49.76% | 299 | 14.44% |

| 1944 | 569 | 29.73% | 1,342 | 70.11% | 3 | 0.16% |

| 1940 | 383 | 23.97% | 1,215 | 76.03% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 281 | 17.12% | 1,360 | 82.88% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 265 | 20.59% | 1,013 | 78.71% | 9 | 0.70% |

| 1928 | 573 | 47.36% | 637 | 52.64% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 179 | 23.55% | 557 | 73.29% | 24 | 3.16% |

| 1920 | 302 | 28.12% | 761 | 70.86% | 11 | 1.02% |

| 1916 | 158 | 26.16% | 437 | 72.35% | 9 | 1.49% |

| 1912 | 71 | 11.22% | 480 | 75.83% | 82 | 12.95% |

| Borough | Incumbent | Title |

|---|---|---|

| At Large | Michael D. Duman | Mayor |

| Cypress | Leroy Bennett | Council Member |

| Chuckatuck | Shelley Butler Barlow | Council Member |

| Nansemond | Lue R. Ward Jr. | Vice Mayor |

| Sleepy Hole | Roger W. Fawcett | Council Member |

| Holy Neck | Timothy J. Johnson | Council Member |

| Suffolk | John Rector | Council Member |

| Whaleyville | LeOtis Williams | Council Member |

| Borough | Incumbent | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Cypress | Karen Jenkins | School Board Member |

| Chuckatuck | Kimberly A. Slingluff | School Board Member |

| Nansemond | Dr. Judith Brooks-Buck | School Board Member |

| Sleepy Hole | Heather S. Howell | Vice Chair |

| Holy Neck | Dr. DawnMarie Brittingham | School Board Member |

| Suffolk | Tyron Riddick | Chairman |

| Whaleyville | Phyllis C. Byrum | School Board Member |

| Title | Incumbent |

|---|---|

| Clerk of the Circuit Court | W. Randolph Carter Jr. |

| Commonwealth Attorney | C. Phillips Ferguson |

| Commissioner of the Revenue | Susan L. Draper |

| Sheriff | Everett "E.C." Harris |

| City Treasurer | Ronald H. Williams |

| Incumbent | Legislative Body | District | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clint Jenkins | House of Delegates | 76th | Democrat |

| Emily M. Brewer | 64th | Republican | |

| C.E. "Cliff" Hayes Jr. | 77th | Democrat | |

| Don Scott | 80th | ||

| John Cosgrove | Senate | 14th | Republican |

| Thomas K. "Tommy" Norment | 3rd | ||

| T. Montgomery "Monty" Mason | 1st | Democrat | |

| L. Louise Lucas | 18th | ||

| Jen Kiggans | House of Representatives | 2nd | Republican |

See also[edit]

- List of people from Hampton Roads, Virginia.

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Suffolk, Virginia

References[edit]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Suffolk population increases 5.1% in 26-month period; Check out your city's report". WTKR. July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "Suffolk has officially surpassed Portsmouth in population. But Hampton Roads as a whole is lagging in growth". The Virginian-Pilot. July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ "Suffolk, Virginia". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Burns, Adam. "American Rails". Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ "Station Search Details".

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing from 1790". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Suffolk city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Suffolk city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Suffolk city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Content.hamptonroads.com". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Erh.noaa.gov

- ^ "The Museum of Railway Timetables (timetables.org)".

- ^ "Suffolk VA Railfan Guide".

- ^ Aaron Applegate, VDOT, city of Suffolk battle over closed Kings Highway Bridge Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, The Virginian-Pilot, May 1, 2006

- ^ John Warren, Flooding blamed on clogged ditches[permanent dead link], The Virginian-Pilot, July 11, 2006

- ^ Content.hamptonroads.com Archived 2007-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Contant.hamptronroads.com Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "City of Suffolk, Virginia". Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived May 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Suffolk Transit | Suffolk, VA". Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "'Pentagon South'". Suffolk News Herald. July 12, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "Hampton Roads News Links". abyznewslinks.com. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ "Coastal Virginia Magazine". Vista Publishing. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ "Hampton Roads Radio Links". ontheradio.net. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ Holmes, Gary. "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006–2007 Season Archived July 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Nielsen Media Research. September 23, 2006. Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Charter Communications Archived 2009-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sheler, Jeff (July 21, 2011). "Redrawn Suffolk boroughs would shift racial makeup". The Virginian-Pilot.

- ^ "Approved Borough Plan". City of Suffolk, Virginia. October 5, 2011. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Chuckatuck Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Cypress Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Holy Neck Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Nansemond Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Sleepy Hole Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Suffolk Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "City Council: Whaleyville Borough". City of Suffolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Zabitka, Matt (July 30, 1952). "UC's Doc Bea Shoots Pool to Sharpen Batting Eye; Triple Off Satchel Paige Brought Words of Warning". Chester Times. p. 16. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ "Suffolk, Virginia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Suffolk Lake Kilby, VA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ David Leip. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved December 8, 2020.