Suanmeitang

| Suanmeitang | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

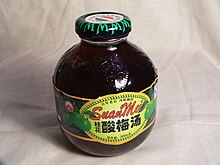

A bottle of suanmeitang | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 酸梅湯 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 酸梅汤 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | sour plum drink | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Suanmeitang[1] or sour prune drink[2] is a traditional[3][4] Chinese beverage made from smoked plums,[5] rock sugar, and other ingredients such as sweet osmanthus.[4] Due to the sour plums used in its production, suanmeitang is slightly salty in addition to being sweet and rather sour.

Suanmeitang is commercially available in China and other parts of the world with Chinese communities. It is often drunk chilled during the summertime, as relief from the heat,[6][7] and is one of the most common summer drinks in China.[4][8] In addition to being widely considered an effective drink for cooling off in the heat, it is also popularly believed to have minor health benefits, such as improving digestion and possibly inhibiting the buildup of lactic acid in the body.[4]

History[edit]

Suanmeitang has existed in some form for over 1,000 years,[4] at least since the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE);[9] there are also reports of a variation called "white suanmeitang" (白酸梅汤) during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 CE).[10] The recipe used today is thought to have been developed at the request of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty during the early 18th century, at which time it was first common in the imperial courts, and was later popularized among common folk when a Hebei citizen created and produced the Xinyuanzhai (信远斋) brand.[4][10] By the 1980s, companies had begun to use industrial methods and technology to mass-produce suanmeitang.[4]

Ingredients and production[edit]

Suanmeitang is made by first soaking sour plums in water, then adding haw, liquorice root,[4] and sweet osmanthus and boiling them together.[9] Rose blossoms may also be added.[2][11] After the mixture is boiled, rock sugar is added to the residue, it is boiled again, and after the beverage has cooled off it is chilled.[2][9]

See also[edit]

- Umeshu – Japanese liqueur

- Maesil-ju – Korean plum wine

- Prune juice

- List of plum dishes

- List of smoked foods

References[edit]

- ^ Garnaut, Anthony (2006). Mandarin: With 3500-word Two-way Dictionary. Lonely Planet. p. 167. ISBN 9781741042306.

- ^ a b c Li-chʻên Tun (1936). Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking as Recorded in the Yen-ching Sui-shih-chi by Tun Li-ch'en. trans. Derk Bodde. Oxford: H. Vetch. p. 58.

- ^ Brown Chiang, Lydia (1995). "Peking Cuisine: The Food of Emperors". Travel In Taiwan. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Li, Rocky (1 July 2008). "Suanmeitang, Cool and Refreshing, Like a Summer Breeze". Beijing This Month. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "Pick up something Chinese". China Daily. 4 June 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Yue, Diana. "This week: Words about plant symbolism" (PDF). Character Builder. The Standard. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Chung-kuo fu li hui (1979). China Reconstructs. University of Michigan. p. 48.

- ^ Rushton, Peter Halliday (1994). The Jin Ping Mei and the Non-linear Dimensions of the Traditional Chinese Novel. Mellen University Press. p. 345. ISBN 9780773498310.

...a favorite Chinese hot weather drink, suanmeitang...

- ^ a b c "Suan Mei Tang". Cocina China (in Spanish). 9 August 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ a b "酸梅汤渐行渐远". 饮食杂谈. 深圳饮食网 (in Chinese). 香港商报 [Hong Kong Commercial Daily]. 30 June 2005. Retrieved 25 September 2023. Translation into English: https://www-szeat-net.translate.goog/news/html/2005-06/3009560010159.shtml?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp.

{{cite web}}: External link in|postscript= - ^ Leung, Albert Y; Leung, Steven Foster (2003). Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients. Wiley-Interscience.