Southern resident orcas

The southern resident orcas, also known as the southern resident killer whales (SRKW), are the smallest of four communities of the exclusively fish-eating ecotype of orca in the northeast Pacific Ocean. The southern resident orcas form a closed society with no emigration or dispersal of individuals, and no gene flow with other orca populations.[1] The fish-eating ecotype was historically given the name 'resident,' but other ecotypes named 'transient' and 'offshore' are also resident in the same area.

The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service listed this distinct population segment of orcas as endangered, effective from 2005, under the Endangered Species Act.[2] In Canada the SRKW are listed as endangered on Species at Risk Act Schedule 1.[3] They are commonly referred to as "fish-eating orcas", "southern residents", or the "SRKW population". Unlike some other resident communities, the SRKW is only one clan (J) that consists of 3 pods (J, K, L) with several matrilines within each pod.[4] As of July 2023, there were only 75 individuals (not counting the captive southern resident, Lolita) in the annual census conducted by the Center for Whale Research.[5] Lolita, also known as Tokitae, or as Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut to the Lummi, was captured during the 1970 Penn Cove capture, and died on August 18, 2023, at the Miami Seaquarium.[6][7]

The world's oldest known orca, Granny or J2, had belonged to and led J pod of the SRKW population. J2 was initially estimated to have been born around 1911, which would mean she would have been 105 years old at the time of her disappearance and death which occurred probably in late 2016.[8] However, this estimate was later revealed to have been based on mistaken information and more recent studies put her at 65–80 years old.[9][10][11]

Society[edit]

Social structure[edit]

All groupings in southern resident society are essentially friendly. The basic social unit is the matriline. A matriline is formed by a matriarch and all her descendants of all generations. A number of matrilines form a southern resident pod, which is ongoing and stable in membership, and has its own dialect which is stable over time. A southern resident calf is born into the pod of their mother and remains in it for life. The southern resident pod is their normal traveling unit. The three southern resident pods form the single clan of this small killer whale community. The clan is possibly a single lineage that split into pods in the past. The clan has a unique stable dialect that shares no calls with other killer whale clans.[12]

The following is a listing of southern resident social units:[13]

- Community

- Southern Resident orca community

- Clans

- J Clan

- Pods

- J Pod (25 members)[a]

- K Pod (15 members)[b]

- L Pod (34 members)

- Matrilines

Note that in several matrilines the matriarch is absent because deceased; nonetheless her descendants continue to associate as a group. Date of census is January 1, 2024.

J11s: J27, J31, J39, J56

J14s: J37, J40, J45, J49, J59

J16s: J16, J26, J36, J42

J17s: J35, J44, J46, J47, J53, J57

J19s: J19, J41, J51, J58

J22s: J22, J38

K12s: K12, K22, K33, K37, K43

K13s: K20, K27, K38, K45

K14s: K14, K26, K36, K42

K16s: K16, K35

L4s: L55, L82, L86, L103, L106, L109, L116, L118, L123, L125

L11s: L77, L94, L113, L119, L121, L124, L126, L127

L22s: L22, L85 (1st cousin), L87 (brother)

L25: L25, the oldest southern resident, has no surviving close relatives since the death of the captive southern resident Tokitae aka Lolita, probably a member of her matriline. L25 travels with the L22s and L11s.

L47s: L83, L91, L110, L115, L122

L54s: L54, L108, L117, plus the unrelated L88 who is an adult male born in 1993 with no living close relatives and who always travels with the L54s.

L72s: L72, L105

L90: L90 is an adult female born 1993 who has no living close relatives. She associates with the L47s.[13][14]

Splitting in L Pod[edit]

While J Pod always travels as a unit, and so does K Pod, L Pod orcas are usually encountered in two separate regular units traveling apart. The L4s, L47s, L90, and L72s are one consistent group; the L11s, L22s, L25, and L54s are the other; but sometimes the four L54s strikingly travel independently of all the others.[15][14] The part of L Pod containing the L11s is often referred to as the L12s after long-lived matriarch L12 Alexis, who died in 2012 after outliving L11 Squirty. L11 had been estimated by association to be L12's daughter, although her birth took place many years before research began.[16][17]

Social system research[edit]

Current knowledge of the society[edit]

The closed society[1] of the southern resident orcas has exceptionally stable social groupings, and they have been encountered with some predictability in the easily accessible, sheltered coastal waters of the Salish Sea, where scientists have been able to study them more readily than many other cetacean populations. There are no unidentified orcas in these waters, and every individual's place in their society is known. Continuous field studies since Michael Bigg's in 1973 have created a near-complete genealogy of the living Southern Residents, with only one individual born prior to the 1970s remaining alive as of August 2023: L25 Ocean Sun.[18][19]

"The social lives of resident killer whales are without doubt as rich and complex as those of the most advanced land mammals."[18] The lifelong bonds within a matriline are the most significant feature of the Southern Residents' social structure.[18] The basic rule is that individuals remain, for life, in the pod into which they were born and to which they are tied by dialect.[20] By 1990, Michael Bigg and fellow researchers had come to that conclusion,[21] and there has been no fundamental change in the Southern Resident social system documented since then.

Evolution of social studies[edit]

In studies of resident orcas, groupings have been inferred from measurements of the association of individuals in travel patterns with the aim of quantifying social bond strength. Relationships have been quantified using two methods: by measuring the distance between whales in photographs, and by counting the number of times individuals appeared together.[22][18]

In the years after Michael Bigg's early surveys, with continuing recordings of births and observations of calves, it gradually became clear that the Southern Resident social structure is a stable ordering of a series of units from small to large according to matrilineal relatedness.[12]

During their long-term studies of resident orcas, researchers John Ford, Graeme Ellis and Ken Balcomb changed their conception of the male's position in the matriline:[23]

"It was not without some surprise that we came to the realization that resident society is so strongly matrilineal. When the study began, many speculated that killer whale pods were the primary breeding units. The mature males in the group were thought to be the "harem masters," and they mated with the pod's cows. The calves and juveniles were therefore their offspring. This was not an unreasonable assumption, however, as many social carnivores live in groups with this kind of social system. But numerous other mammals, including some of the most socially advanced species, such as primates, live in multi-generation, matrilineal societies. However, in most of these matrilineal species, offspring, usually just males, disperse from the group upon reaching maturity and join or form new groups. This is probably also the case for certain other species of toothed cetaceans, such as bottlenose dolphins and sperm whales, which appear to live in matrilineal groups for at least part of their lives. Dispersal is thought to be primarily a mechanism by which the animals prevent excessive inbreeding."

The Southern Resident social system never separates the sexes for long. The fact that the sons stay with their mothers for life and are their closest associates is exceptional.[23] The males in the smallest social unit, the matriline, are all descendants of the matriarch.[12] In the case of resident killer whales, association has only indicated maternal relatedness. Fathers are not present in the same matriline as their offspring. Paternity remained unknown prior to genetic studies.[18]

In 1978, John Ford began the highly innovative thesis research that revealed killer whale dialects.[24] Dialects came to partially supplant association modeling as a method for verifying the social structure because the orcas can "choose different travel associates at different times, based probably on social factors, such as age and sex composition. Dialects are very stable over time, however, and appear to better indicate pod genealogies than do associations."[25]

The acoustic evidence of dialects revealed the clan to be the largest vocal, and probably matrilineal, unit. Because the Southern Resident community is only a single clan, the nature of the larger, community level of social grouping is clearer in the multi-clan Northern Resident community. Unlike the clan, the community is "defined by travel patterns and not on genealogy or acoustics."[23]

Stability in social groups[edit]

The social units of resident orcas are mostly very stable. Especially in periods of population growth, however, travel patterns can reveal the gradual splitting of pods into two separate units, more evidently in the Northern Resident community.[20] In the Southern Residents, a tendency for splitting in L Pod, the largest, has been recorded since surveys began. Although pods can split, the matrilines remain stable.[26] Normally when the mother dies, moreover, her offspring maintain the matriarch's matriline. Nevertheless, a matriline in which there are no living potentially reproductive females is destined to die out as a social unit, no matter how many males or post-reproductive females are in it.[20]

Foraging implications[edit]

The foraging specializations that distinguish between orca populations appear to represent distinct animal cultures.[27] The sympatric transient (Bigg's) orcas travel in small, family groups, with individuals cooperating to kill and eat marine mammals together.[28] By contrast, the large, multi-family, multi-generation southern resident pods behave in a way that may increase their success in hunting the salmon that forms the southern resident orca diet.[29]

Salmon migrations aggregate the fish in different locations at different times of year, and the resident pods' movement patterns coincide with these salmon runs, which are especially large towards large rivers. The orcas seek to move from one good feeding spot to another, learning from elders the local seasonal movements of salmon. In the southern resident territory, Chinook salmon runs occur in every season, depending on the location.[29]

When they find the salmon, the orcas spread out, and mostly eat the fish individually, although some sharing occurs, especially from a mother to her offspring. Pod members use underwater calls from their dialect to maintain contact at a distance.[29]

Researchers concluded that "making a living on salmon undoubtedly requires specialized knowledge that is passed on from generation to generation, and a whale's survival is enhanced by staying with its pod and taking advantage of these behavioural traditions."[29]

Sport, recreation, and socializing[edit]

Orcas have good vision above the surface as well as below.[30] Southern resident socializing includes a great variety of tactile interactions and surface activities. Breaches are a speciality of the southern residents, as well as other surface behaviors including spyhopping, tail slapping, and pec slapping (with pectoral fins). Researchers wrote that in play, they “often chase one another, or roll and thrash together at the surface.”[31][32] They "have been seen riding the wake of all types of vessels, from small skiffs to the largest cruise ships."[30] Juvenile southern residents spend more time in these activities. Vocalizations produced during socializing are excited, highly variable and less confined to the stereotyped calls of the dialect.[33]

Southern residents also playfully interact with objects, in particular floating driftwood and kelp.[34][31]

Kelping[edit]

While northern resident orcas are culturally known for beach rubbing, southern residents have never been seen to do that. On the other hand, southern residents have long been observed seeking tactile pleasure in kelping. This behavior can be seen close to shore from Lime Kiln Point State Park. The orcas drape the kelp over their body or lift it above the water with their tail flukes.[35][32][36][37]

Greeting ceremony[edit]

A particular way of socializing among southern resident pods is a behaviour referred to as a "greeting ceremony." The pods in the clan sometimes forage in the same area, but often travel separately to locations far apart. Sometimes when two pods reunite after travelling apart for a period, all the members of each pod group up in formation and swim side by side at the surface in a precise line facing the other pod's line. They pause when 10 to 50 metres (33 to 164 feet) apart. “After less than a minute, the two groups then submerge and a great deal of social excitement and vocal activity ensues as they swim and mill together in tight subgroups," researchers observed.[35]

Caring behavior[edit]

Epimeletic behavior[edit]

“Epimeletic” refers to the behavior of animals standing by others in danger, or caring for injured, ill or dead individuals.[38][39] Examples in cetaceans include when a mother carries a dead calf, or when an animal is helped to survive by being lifted by others to the surface to breathe.[40] When healthy individuals stay with a distressed individual in danger, this epimeletic behavior is called standing by. The companions may also attempt to protect or rescue the individual from the danger.[38][41]

Early observations of epimeletic behavior[edit]

- During an ill–conceived Marineland of the Pacific capture attempt in 1962, a female southern resident was lassoed. A male joined her to thump the collector's boat with their flukes, but she was shot and killed as a result.[42]

- During Moby Doll's capture in 1964, pod–mates raised the J Pod juvenile to the surface after he was harpooned.[43] One orca followed as the captors’ boat led Moby Doll by the harpoon line from Saturna Island to Vancouver.[44] Plausibly the same orca exchanged long–distance pulsed calls with him over two miles (3.2 kilometres) the next day when he was at Burrard Dry Dock.[45]

- In 1967, K Pod orcas were being herded in the Yukon Harbor capture operation. Two members of the pod escaped from nets. Even though they had already seen a relative die after being entangled,[46] they did not flee from the scene. Rather, they went towards their still trapped pod–mates and kept swimming around the outside of the capture net,[47][48] “squeaking” vocally at those within it.[49]

Mourning[edit]

One day in 2010, L72 Racer was seen with her dead neonate in her mouth. She then travelled carrying it on her rostrum. Despite the body regularly sliding off into the sea, she would double back and retrieve it and resume carrying it on her rostrum. This was observed throughout the day for over six hours. The next day, when she was seen again, the carcass was gone.[50][51]

In 2018, J35 Tahlequah carried her dead neonate for 17 days and an estimated minimum of 1,600 km.[52][53][54] The newborn calf was alive and swimming with her northeast from Race Rocks when first spotted by a Center for Whale Research associate. When other researchers from the center located the pod of orcas again a half hour later near Discovery Island, the neonate was dead and being carried on J35 Tahlequah's rostrum. She often had to make long dives to retrieve the dead neonate when it fell off.[55][52][56] She was likely unable to forage for the next 17 days as she carried the dead calf,[52] an act that requires a great deal of energy.[41][54] When Bearzi et al. published their retrospective survey of 78 reports of cetacean responses to dead conspecifics—coincidentally the month before J35 Tahlequah's extraordinary effort—they wrote that up to that time, cetaceans had been “documented carrying a dead and decomposing individual for up to about one week.”[57] Decomposition was significant in J35 Tahlequah's case. On day 17, the day the calf disappeared, researchers observed, “The calf's body had lost all of its form and had opened on the ventral side, exposing the inner organs.”[52]

Epimeletic behaviors including an initial rescuing response understandably aid survival of the species,[38] but when the carcass is decomposing after some time, other explanations may be needed.[57][41] Delphinidae species occurred in 92.3% of the records of postmortem attentive behaviour (PAB) by cetaceans. Attending dead or dying conspecifics correlates with sociality and the dependence of calves, as well as intelligence (measured by brain size and encephalization).[58][57] In odontocete cetaceans such as orcas and dolphins, “selective pressure towards a large brain resulted from cognitive demands imposed by mutual dependence within a network of associates, and the benefits of developing complex social skills.”[59]

Have these cetaceans failed to recognize the individual has died? When cetaceans care for the dead, possibly a strong attachment has resulted in grieving.[57] The behavior is not frequently reported, and difficulties in observing wild cetaceans make for a small sample size of verifiable incidents; there is much more to learn about cetacean responses to death.[57]

Recent births and deaths[edit]

The Center for Whale Research records all births and deaths, and collects demographic data of the southern resident orca population.[60] From 1990 to 2023, 61 southern resident orca calves have survived beyond birth, while 107 southern residents have died.[5]

In late 2014, J50 Scarlet was born into the J pod; her mother J16 Slick was 42 years old, the oldest recorded age for an orca mother.[61] In August 2018, the pod attracted international attention after the death of a female calf born to J35 Tahlequah, who carried the body for 17 days.[62]

In September 2020, J57 Phoenix was first seen traveling with J35 Tahlequah and is her second calf. His sex was determined as male a short time later.[63] On September 24, 2020, J58 Crescent's birth was observed and she was confirmed as the second calf of J41 Eclipse by the Center for Whale Research the next day. Her sex was later confirmed as female by the Center for Whale Research.[64]

Only two calves were born in 2022 and the total population of the Southern Residents fell to one of its lowest numbers since the end of the live-capture era in 1974, when 71 individuals were counted. Only 73 Southern Residents were counted in the July 1, 2022, census conducted by the Center for Whale Research. This consisted of 32 whales in L Pod, its lowest point since 1976, 16 orcas in K Pod, its lowest in the last 20 years, and 25 in J Pod, which remained stable. In the year up to July 2022, three individuals died: K21, K44, and L89.[65] On June 30, 2023, Center for Whale Research confirmed the birth of two new calves in the L12s. In the encounter on the same day, both appeared healthy, and were at least two months old. They were designated L126 and L127. The pair are cousins of the same age in the same matriline.[66]

Tokitae (Lolita), known as Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut to the Lummi, died on August 18, 2023, at the Miami Seaquarium.[6]

Sounds[edit]

Orca vocal production is classified in three categories: clicks, whistles, and pulsed calls.

Clicks made by toothed whales are very brief vocal sounds produced in rapid series for echolocation.

"Whistles are non-pulsed continuous signals with much simpler harmonic structure"[67] than pulsed calls. Whistling is a minor component of southern resident orca vocalizations, "whereas whistles are the primary social vocalization among the majority of Delphinidae species."[67][68]

The pulsed calls of orcas may sound to humans like forms of speech, music, or wordless squeals,[69][70] "with distinct tonal qualities and harmonic structure. These calls, typically 0.5–1.5 s in duration, are the primary social vocalization of killer whales."[67] "By varying the timbre and frequency structure of the calls, the whales can generate a variety of signals...Most calls contain sudden shifts or rapid sweeps in pitch, which give them distinctive qualities recognizable over distance and background noise," wrote the researchers.[71]

Echolocation[edit]

Echolocation in an orca was first described by William E. Schevill and William A. Watkins in their study of the J Pod orca Moby Doll.[72]

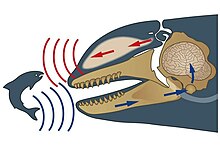

The orca produces vocalizations inside the blowhole, its nose. Echolocation clicks are anatomically reflected forwards, and focused and directed by fats in the melon.[73] The orca's anatomy is adapted to hearing underwater rather than in air. Incoming sounds, including echoes, are collected by the lower mandible, which functions as the orca's outer ear. The remaining parts of the two ears, in the auditory bullae, are connected to the rear of the lower mandible. Inside the lower mandible, sound travels through wide fat pads acting as ear canals, reaching the orca's version of eardrums, bony tympanic plates, which vibrate in response. From there, sound data are transmitted through the middle and inner ears to the brain, which is able to resolve echoes into information.[74]

Dialect[edit]

Cetacean cultures are marked by socially-determined vocal traditions. Toothed whales, including orcas, are known for large brains and complex social structure with correspondingly complex vocal communication systems.[75]

Some vocalizations produced by southern residents are unrepeated, but the majority are repetitions of the same calls that have been produced for many years in a specific social group. These distinct and traditional calls are referred to as discrete, or stereotyped calls. Each southern resident pod's set of discrete calls is their dialect.[67]

The three southern resident pods share some calls with one another, and also have unique calls. Together, the three pods form a clan, J-Clan. Clans share no calls with other clans. Thus the three clans of northern resident orcas and the single southern resident clan share no calls.[69]

Among orcas born and observed in captivity, calves at first babbled without making the discrete calls of adults. The calves gradually began to make the calls their mother made, but never made the calls of other, unrelated orcas. In the wild, juvenile southern residents use only their matrilineal pod's dialect, including a limited number of vocalizations shared with other pods. Southern residents do not make the calls unique to a different pod's dialect even though southern resident pods frequently mix with the other pods in the clan and the orcas could in theory learn the other pods' calls.[76] Discussing the function of resident orca dialects, researchers John Ford, Graeme Ellis and Ken Balcomb wrote, "It may well be that dialects are used by the whales as acoustic indicators of group identity and membership, which might serve to preserve the integrity and cohesiveness of the social unit."[69]

Identifying calls and whistles[edit]

Discrete orca calls "can be readily identified by the trained ear or sound analyzer—some dialects are so distinctive that even an inexperienced listener can immediately discern the differences."[69]

"J-Clan discrete calls were classified alphanumerically"[67] by John Ford[77] "with the letter “S” preceding the number to indicate that it is from a Southern Resident (S1, S2, etc.). All three pods share some calls in common, while other calls are produced by only a single pod,"[67] or by K Pod and only one of the other two pods. For example, the S42 is one of three pulsed calls produced in all three pods, whereas the S17 is not produced in J Pod. It is unsurprising and perhaps genealogically significant that it is K Pod that 'pairs' with the other two pods, while J Pod and L Pod are vocally far apart.[77][69]

Because it is unique to a particular group of orcas, a dialect makes it possible to identify which orcas are present from acoustic evidence without visual detection.[78] At the Center for Whale Research, Ken Balcomb identified which pods were passing from their pulsed calls relayed by distant hydrophones.[70]

The most common call for identifying each pod is:

S1: J Pod, also produced in K Pod

S16: K Pod, also produced in L Pod

S2iii: L12s

S19: rest of L Pod

Vocal divergence between the two parts of L Pod supports the idea that L Pod may actually (almost?) be two pods.[77] [78]

While whistles are rarer than pulsed calls among southern resident orcas, many are also stereotyped and form part of their dialects. Southern resident orca stereotyped whistles have been given "a similar alphanumeric designation (SW1, SW2, etc.)."[67]

Meaning of vocalizations[edit]

Early research found that most sequences of orca calls included the same call being repeated at least five times.[79][80] This would not occur if the calls were letters or words in a syntactical language.[80]

In the example of the northern resident orcas, shared discrete calls are not necessary for social interactions, as the three clans in this community mix without sharing any discrete calls in their dialects. On the other hand, as markers of group identity, unique discrete calls may help matriarchs keep track of their pod mates when navigating or mixing with other pods in murky waters.[81] The discrete calls "appear to serve generally as contact signals, coordinating group behaviour and keeping pod members in touch when they are out of sight of each other."[71]

Researchers have been unable to find a consistent correlation of specific calls with specific behaviors. Alexandra Morton's observations of the captured northern residents Corky and Orky found a different kind of correlation, a finding supported by observers of orcas in the wild.[81] The pair of orcas repetitively called in "long 'conversations' while floating side by side" without engaging in any behaviors requiring the exchange of any information. Morton found, nonetheless, an association of some calls with particular moods, or shifts in mood.[82]

Ken Balcomb spoke with Carl Safina about the issues:[83]

"They don’t seem to be saying stuff to each other like 'Big fish here,' or whatever. They don’t seem to have one call for ‘prey’ and another for 'hello.'" Each of their calls may be heard whenever the whales are vocalizing; it doesn’t matter what they’re doing. Ken feels certain, however, that "they know—from just a peep—who that was and what it’s about. I’m sure that to them, their voices are as different and recognizable as our voices are to us. I’m pretty sure they have names for each other like other dolphins do, and that right now some of what we’re hearing repeated are those signature calls." There may be more communicated in the emotion that comes across. "A call might sound like Ee-rah’i, ee-rah’i," says Ken. "Does that mean something specific? Or does its intensity carry meaning? When the pods congregate, you sense intensity, excitement; it sounds like a party. When they’re excited, the calls get higher and shorter—in other words, shrill." The calls might not have syntax, but what comes across among the whales is who, where, mood, and, perhaps, food.

Spectrograms do depict subtle differences among instances of discrete calls, which might communicate emotional state and current behavior.[84]

Not all vocalizations are repetitive and discrete. When closely socializing, for example, the "whales employ a wide range of highly variable" vocalizations, according to researchers.[35]

Excitement sound[edit]

In the SRKW catalog, one call, the S10, has come to be viewed in a different light to the others. Shared by all three pods and common in multi-pod aggregations such as superpods, the S10, with a duration of several seconds, has been likened to human laughter by many listeners over the years.[84]

A 2011 study compared sixty-nine calls in tests in which the nine listeners were blind to the sources of the calls. The samples were drawn from multiple North Pacific clans. The results categorized the S10 in a group of calls that showed some variations but seemed associated. The researchers concluded that, with minor variation, this was one call that crossed the cultures of clans and even ecotypes, and was not acquired through social learning like the rest of the repertoire. They identified it as being an 'excitement' call "associated with arousal behaviours" of various kinds.[85] Recordings of this 'excitement call' included northern as well as southern residents, and also Gulf of Alaska transients, who produce it in characteristic celebrations after a kill. Each ecotype's behavior may be different, but the happy emotional state of excitement is common to both behaviors.[84]

Moby Doll[edit]

A southern resident initiated the scientific study of orca sounds. When the juvenile J Pod member later named Moby Doll was captured in 1964, it was a watershed for the then very misunderstood and hated species. He began the transformation of the species' public image,[86] and made possible the first closeup studies of a live orca.

Orcas had been recorded in the field five times previously; three of the recordings had been of J Pod. J Pod had been recorded in Dabob Bay on October 20, 1960, by US Navy personnel;[87][88] and in Saanich Inlet by Canada's Defence Research Establishment Pacific on February 19, 1958, and in spring, 1961.[88] These historical field recordings would ultimately provide a suggestive reference for the stability in time of discrete calls.[89]

Harold Dean Fisher recorded Moby Doll at Burrard Dry Dock, and the tape he kept at UBC would years later have great significance for pivotal researcher John Ford (see below), who heard it as a student.[90]

Schevill and Watkins' study of Moby Doll created the fundamental basis for understanding orca sounds.

William E. Schevill first heard the underwater sounds of whales during World War II, in the fight against U-boats. He was inspired to become a cetologist and pioneer in the study of whale sounds. He had already studied 20 other species of cetacean when in August 1964 he travelled to Vancouver with his Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution colleague William A. Watkins to study Moby Doll for three days.[91][92]

At Moby Doll's seapen at Jericho Beach the scientists found an acoustically exceptional site for their work. Following Donald Griffin's pioneering work with bats, Schevill had been the first to describe echolocation in whales.[93] The little southern resident gave him proof that orcas were among its users. Schevill also found that Moby Doll did not use it continually, but was content to use only his memory or eyesight if they sufficed.[94][90] The scientists demonstrated the sharp, directional nature of his echolocation, giving support to Kenneth Norris's new hypothesis that the fatty melon of a delphinid might function as an acoustic lens.[95] The orca's clicks were narrower-band and lower-frequency than those of other delphinids.[94]

Schevill and Watkins examined orca pulsed calls for the first time, too. They labeled them "screams." Moby Doll never produced the "whistle-like squeal" of other delphinids.[92] Rather, these 'screams' were produced in the same way as echolocation, but in pulses of clicks at a much faster repetition-rate, with the strong harmonic structure masking the individuality of the clicks. Moreover, whereas other delphinids could produce clicks and whistles concurrently, Moby Doll never produced clicks and pulsed calls simultaneously, which was supporting evidence that both of his types of sound were produced by the same mechanism.[94] (In later research, however, John Ford did find some whistling to be a minor component of southern resident vocalizations, "whereas whistles are the primary social vocalization among the majority of Delphinidae species.")[67] The scientists noted that there was much variation in their recordings, but certain patterns were general. The pulses had a "strident" quality due to their harmonic structure, with many strong harmonics, and they were much louder than the echolocation. Moby Doll was able to change the frequency and harmonics in the pulses and vary the signals.[96]

John K.B. Ford saw Moby Doll the day the captured orca was on display at Burrard Dry Dock. Ford was nine at the time. While he was studying science at UBC, he recorded whale sounds. He heard zoology professor H.D. Fisher's tape of Moby Doll’s pulsed calls. "These calls were burnt into my acoustic memory," Ford said when interviewed by Mark Leiren-Young.[90] In time, the calls would make it possible for Ford to posthumously identify that Moby Doll had come from J Pod.

In 1978, Ford began making the recordings of orcas in British Columbia that he would use for his Ph. D. thesis. After starting with northern residents, in the autumn he traveled to the mouth of the Fraser River to make his first recordings of southern residents.[90][97]

Ford recalled the moment he heard a call by Moby Doll being produced by living southern residents:[90]

"I put the hydrophone on the side of the boat, and I was recording the sounds, and they all sounded pretty alien to me, because the dialects are very different from the northern residents, which I had started becoming familiar with, and then, all of the sudden, in the middle of these calls, is the one I remembered so vividly from the Moby Doll tapes. I realized, in that moment, that this was the pod Moby Doll must have come from. It was J pod."

What Ford was hearing was a scientific breakthrough in the study of mammals: it was evidence of an acoustic culture unique to a single pod which outlived an individual mammal. "It was a wonderful moment out there in the boat when I recognized the sounds coming from J pod to be Moby Doll’s signature sounds," Ford said.[90]

Location[edit]

The southern residents have been seen off the coast of California, Oregon, Washington, and Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Historic sightings and more recent data from satellite-tagged individuals show frequent use of coastal waters as far south as Monterey Bay, California in the winter and early spring. Members of L pod have been seen as far north as southeast Alaska. During the late spring through fall, the southern residents tend to travel around the inland waterways of Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and southern Georgia Strait - an area known as the Salish Sea.[98] More information is now available about their range and movements during the winter months, which appears to follow the return of Chinook salmon to major rivers in California and North America's Pacific Northwest region.

Relationship with the Lummi Nation[edit]

The Lummi Nation has had a relationship with southern resident killer whales in the Salish Sea for thousands of years. Early proof of this can be seen in the recorded oral tradition of the tribes in the Puget Sound with the story "The Two Brothers' Journey to the North", which was first recorded in the mid-1850s.[99] The Lummi Nation refer to the southern resident killer whales as qwe'lhol'mechen, which translates to "people beneath the waves".[7] The term Sk'aliCh'elh is used to refer to the J, K, and L pods of the Southern Resident orcas by their "Lummi family name".[7] The Lummi Nation considers the southern resident killer whales as kin and has sacred ceremonies dedicated to them.[100]

Due to pollution, lack of prey, and previous whaling efforts, the orcas’ populations have recently been in decline. The Lummi have been making efforts using Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)[clarification needed] to support the orca population.[101] They are concerned about the future of the orcas if environmental issues that negatively impact the orcas continue to persist, and have been seeking support from agencies with the government to work harder in upholding the integrity of orca populations.[100]

J17, or Princess Angeline, is one such orca that has been under the care of the Lummi people in recent years. Before J17 passed away in 2019, the Lummi people practiced orca feeding ceremonies with J17.[100][102] The ceremony for the spiritual feeding involves first leaving the mainland on a boat to find a proper location. Next is the releasing of live and dead salmon, the live salmon to feed J17, and the dead salmon to honor the qwe'lhol mechen ancestors. The purpose of the ceremony is to hope that the condition of the orcas improves as well as to honor the orcas' ancestors.[100] In relation to such feedings, Lummi matriarch Raynell Morris has explained that "Here at Lummi when we see a relative starving, we don’t go in and do medical tests to see how much they are starving. We know they are and we do the right thing and we feed them."[103]

Distinguishing features[edit]

- Dorsal fin: rounded at the tip (leading edge) and positioned over the rear insertion of the fin towards the back.

- Saddle patch: typically seen as an "open" saddle patch; five different pigmentation patterns have been reported with similarities noted among clans within a community.[104]

Diet[edit]

Southern residents are exclusively fish-eating orcas. From visual sources, necropsy, and feces collection, the following food preferences have been reported:[4]

- Salmon 97%

- Other fish 3%

- e.g. Pacific herring and quillback rockfish

While Chinook are less abundant than other salmon, they are larger and have a high fat content, both of which make them apparently preferable to other species.[105]

Although resident orcas are often in the vicinity of seals and porpoises, which are eaten by transient (Bigg's) orcas, they typically ignore them. Even when on rare occasions they attack them, they do not eat them—the attacks are harassment or sport.[105]

Threats[edit]

The primary, interactive threats to this very small population have been listed as:[106]

- Insufficient prey

- High levels of contaminants in prey and water

- Impacts and sound from vessels

Decline in prey[edit]

The depletion of large quantities of fish in the marine environments, while personal fishing in the salmon's upstream spawning grounds has continued, have further depleted stock replenishment.[107] Aquaculture has had a negative effect on world fish supplies,[108] including through the spread of pathogens to the wild fish stock. A study also found that Chinook salmon found in South Puget Sound have less fat than those farther north, causing an increased need for consumption.[109] Due to four dams in the Lower Snake River Dam System, native salmon flow has been heavily restricted, endangering both Chinook Salmon and Southern Resident Killer Whales.

Chemical contamination[edit]

Pacific Northwest orca are among the most contaminated marine mammals in the world, due to the high levels of toxic anthropogenic chemicals that accumulate in their tissues.[110] Implicated in the decline of the southern resident orca population, these widespread contaminants pose a large problem for conservation efforts. While many chemicals can be found in the tissues of orca, the most common are the insecticide DDT, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).[111] Each of these have detrimental physiological effects on orca,[112] and can be found in such high concentrations in dead individuals that those individuals must be disposed of in hazardous waste sites.[113]

Correlative evidence shows orca may be vulnerable to effects of PCBs on many levels. Research has identified PCBs as being linked to restricting development of the reproductive system in orcas and dolphins.[114] High contamination levels leads to low pregnancy rates and high mortality in dolphins. Further effects include endocrine and immune system disruption, both systems being critical to mammalian health and survival.[112] A study examining 35 Northwest orcas found key genetic alterations that caused changes to normal physiological functions.[115] These genetic level interferences, combined with the varied effects of PCBs at other physiological levels, suggest these contaminants may be partially responsible for declines in orca populations.

Many of the chemicals that have been found to be toxic to the orca population continue to be widely used.[116] Conservation efforts are said to have difficulty making progress if the chemicals that harm the orcas continue to pollute the water they live in.[116]

Marine noise[edit]

Noise and crowding from tour boats and larger vessels interrupt foraging behavior, or scare away prey. The noise can mask echolocation causing difficulty with catching prey.[117] Also, sonar is speculated to cause hemorrhaging, and possibly death.[118]

Capture era[edit]

The Southern Residents "deal with an unnatural age gap within the population, for which the capture era is to blame. Female whales that would have been the current generation’s matriarchs, born in the 60s and early 70s, are gone—many were victims of a life of imprisonment that claimed them at much too young of an age. By 1987, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut [Tokitae] was the last known survivor of the Southern Resident population still in captivity."[119] The effects of the capture era have been felt in the reduced population ever since.[119]

Population numbers[edit]

Before the 20th century, orca populations in the Salish Sea likely numbered over 200.[120] Fishermen considered the orcas to be nuisances and competition. About 25% of captured, immature orcas carried evidence of already having been wounded by shootings.[27] Between 1962 and 1977, 68 orcas in total were identifiably captured or killed during capture operations in British Columbia and Washington State. By pod or capture location, 48 of them were identified as southern residents. The captures were selective for physically immature orcas less than 4.5m in length: 30 of the 48 southern residents lost to their community were in this category.[121][19] Until the capture of these whales was banned in Canada and the US in 1976, the number of whales was reduced significantly.[120] Michael Bigg censused a total of 67 southern residents in 1976. 53 were older orcas, and 14 were assessed by size to be "young"—born during the capture period or after the last southern resident capture in 1973.[122][121] The community recovered to a size of 99 in 1995 then declined[35] to reach the status of endangered that it holds today.[120][123]

Yukon Harbor capture[edit]

The first large capture event was the trapping of probably much of K Pod[122] in Yukon Harbor on the west side of Puget Sound in 1967.[124] Of the 15 trapped southern residents, three died in the operation, and five were taken into captivity,[125][48][126] roughly halving the population of K Pod.[122]

How many of the other southern residents lost to the community in the 1965–1973 captures were from K Pod is unclear.[121] As of 2023, the one living K Pod survivor of the capture era was grandmother and matriarch K12 Sequim, who was born in 1971 or 1972.[127][13]

1970 Penn Cove capture[edit]

On a single day in 1970 in Penn Cove off Whidbey Island in Washington state, approximately 80 orcas were herded into net pens and 7 young orcas were captured to be placed in aquariums and theme parks.[7] The orca commonly known as Tokitae, or as Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut to the Lummi, was captured during this event, and died on August 18, 2023, at the Miami Seaquarium. [6][7]

Conservation efforts[edit]

United States[edit]

Both NOAA and the Lummi Nation have been making efforts to feed bolster the Southern Resident population, however, there is disagreement in the types of conservation efforts that should be implemented.[101] The Lummi believe that immediate action is necessary in order to sustain the already unhealthy orca populations, while NOAA believes in observing before taking action. The Lummi are using "traditional ecological knowledge" practices to help sustain the orca population, including feeding of malnourished individuals, which has been criticized by NOAA as unsustainable.[101] The groups have worked together though to create "helpful protocols" and strive for the overall wellbeing of the orcas.[100]

Current conservation efforts are listed as:[128]

- Support salmon restoration efforts

- Clean up existing contaminated sites

- Continue evaluating and improving guidelines for vessel activity

- Prevent oil spills

- Continue Agency coordination

- Enhance public awareness

- Improve responses to live and dead orcas

- Coordinate monitoring, research, enforcement

- Conduct research

- Cooperation and coordination

Washington state[edit]

There was a Washington state-wide task force created in March 2018 to make recommendations on how to preserve the Southern Residents from extinction.[129] Some of the recommendations include stopping the use of hormone disruptors and other toxins in consumer products[130] and removing dams that interfere with the salmon's access to breeding grounds.[131]

The city council of Port Townsend issued a non-binding resolution in 2022 declaring that the Southern resident orcas have rights of nature and should be protected due to the orca's significant "cultural, spiritual, and economic" value to the state and its citizens.[132]

Canada[edit]

On October 31, 2018, the Government of Canada committed $61.5 million to implement new protections for the Southern Residents.[133]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Research". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "The Endangered Species Act - Protecting Marine Resources". www.federalregister.gov. Office of the Federal Register. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "Recovery Strategy for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Canada". April 27, 2011.

- ^ a b National Marine Fisheries Service (2008). "Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca)". National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Region, Seattle, Washington. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "Southern Resident Orca Community Demographics". Orca Network. July 6, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Our hearts are broken. Our beloved Toki has passed away". Friends of Toki. August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "One stolen whale, the web of life, and our collective healing". Grist. October 28, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Balcomb, Kenneth C. (December 31, 2016). "J2: In Memoriam". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ "Oldest Puget Sound Orca, 'Granny,' Missing and Presumed Dead". abcnews.go.com. ABC News. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Tegna. "Oldest Southern Resident killer whale considered dead". KING5.com. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Podt, Annemieke (December 31, 2016). "Orca Granny: was she really 105?". Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c "Orca Identification". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "2022 Encounters". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ "2021 Encounters". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, pp. 71–78.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 23.

- ^ a b "Orca Population". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Bigg et al. 1990, pp. 403–404.

- ^ a b c Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Ford 1984.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 26.

- ^ a b Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 20.

- ^ a b Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 32.

- ^ a b Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 30.

- ^ a b "Behaviors". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, p. 95.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Bearzi, Giovanni; Reggente, Melissa A.L. (2018). "Epimeletic Behavior". In Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M.; Kovacs, Kit M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third ed.). Academic Press. pp. 337–338. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00121-7. ISBN 9780128043271.

- ^ "epimeletic". Collins English Dictionary. 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ "Altruistic behaviour". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c Castro, Joana; Oliveira, Joana M.; Estrela, Guilherme; Cid, André; Quirin, Alicia (2022). "Epimeletic Behavior in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the South of Portugal: Underwater and Aerial Perspectives". Aquatic Mammals. 48 (6): 646–651. doi:10.1578/AM.48.6.2022.646. S2CID 253393219.

- ^ Hoyt, Erich (2013). Orca: the whale called killer (eBook ed.). Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 9781770880672.

- ^ Colby 2018, p. 52.

- ^ Colby 2018, p. 58.

- ^ Colby 2018, p. 61.

- ^ Colby 2018, p. 106.

- ^ Hannula, Don (February 23, 1967). "Female Whale Dies in Griffin's Pen". The Seattle Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b Hannula, Don (February 25, 1967). "Whale Calf Moved To Griffin Aquarium". The Seattle Times. p. A.

- ^ "LSD Tests on Griffin's Whales By U. of W. Scientist Possible". The Seattle Times. February 24, 1967. p. 44.

- ^ Reggente Melissa A. L.; et al. (2016). "Nurturant behavior toward dead conspecifics in free-ranging mammals: new records for odontocetes and a general review". Journal of Mammalogy. 97 (5): 1428–1434. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyw089.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Shedd, Taylor; Northey, Allison; Larson, Shawn (2020). "Epimeletic behaviour in a Southern Resident Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 134 (4). doi:10.22621/cfn.v134i4.2555.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda V. (July 24, 2018). "Southern-resident killer whales lose newborn calf, and another youngster is ailing". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ a b Mapes, Lynda V. (August 10, 2018). "Researchers won't take dead orca calf away from mother as she carries it into a 17th day". phys.org. The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ "Encounter #52 - 24 July, 2018". Center for Whale Research. July 24, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Killer whale spotted pushing dead calf for two days". BBC. July 27, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Bearzi Giovanni; et al. (2018). "Whale and dolphin behavioural responses to dead conspecifics". Zoology. 128. Elsevier GmbH: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2018.05.003. hdl:10023/17672. PMID 29801996.

- ^ Reggente Melissa A. L. V.; et al. (July 16, 2018). "Social relationships and death-related behaviour in aquatic mammals: a systematic review". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 373 (1754). doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0260. hdl:2318/1688965. PMC 6053979. PMID 30012746.

- ^ Bekoff, Marc (May 24, 2018). "Dolphins' Big Social Brains Linked to Attention to the Dead". Psychology Today. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ "Orca Survey Since 1976". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Gamby, Sonja (January 7, 2015). "Endangered species has hope with the birth of a baby killer whale". modvive.com. Modus Vivendi. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda V. (August 6, 2018). "Lummi Nation, biologists prepare to feed starving orca. But where is she?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "J57". Center for Whale Research. September 6, 2020. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ "Update: J58 is a girl!". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda V. (September 29, 2022). "Southern resident orca pod falls to lowest number in 46 years". The Seattle Times. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Not ONE But TWO New Babies in L Pod!". Center for Whale Research. June 30, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Souhaut M; Shields MW (2021). "Stereotyped whistles in southern resident killer whales". Aquatic Biology. 9. PeerJ: e12085. doi:10.7717/peerj.12085. PMC 8404572. PMID 34532160.

- ^ Vincent M Janik; Peter J.B Slater (1998). "Context-specific use suggests that bottlenose dolphin signature whistles are cohesion calls". Animal Behaviour. 56 (4). Elsevier Ltd.: 829–838. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0881. ISSN 0003-3472. PMID 9790693. S2CID 32367435.

- ^ a b c d e Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 21.

- ^ a b Safina 2015, p. 308.

- ^ a b Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 96.

- ^ Schevill & Watkins 1966, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Cranford TW (2000). "In Search of Impulse Sound Sources in Odontocetes". In Au WW, Popper AN, Fay RR (eds.). Hearing by Whales and Dolphins. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research series. Vol. 12. New York: Springer. pp. 109–155. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1150-1_3. ISBN 978-1-4612-7024-9.

- ^ Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J.G.M.; Bajpai, Sunil; Hussain, Taseer; Kumar, Kishor (2007). "Sound transmission in archaic and modern whales: Anatomical adaptations for underwater hearing". The Anatomical Record. 290 (6): 716–733. doi:10.1002/ar.20528. PMID 17516434. S2CID 12140889.

- ^ Marino L; Connor RC; Fordyce RE; Herman LM; Hof PR; Lefebvre L; et al. (2007). "Cetaceans Have Complex Brains for Complex Cognition". PLoS Biol. 5 (5): e139. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050139. PMC 1868071. PMID 17503965.

- ^ Wieland Shields 2019, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c Ford, John (1987). "A catalogue of underwater calls produced by killer whales (Orcinus orca) in British Columbia". Canadian Data Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 633: 1–165. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Orca Acoustics". Orca Behavior Institute. January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Hoelzel, AR; Osborne, RW (1986). "Killer whale call characteristics: implications for cooperative foraging strategies". In Kirkevold, Barbara C; Lockard, Joan S (eds.). Behavioral Biology of Killer Whales. Zoo biology monographs. Vol. 1. A.R. Liss New York.

- ^ a b Wieland Shields 2019, p. 82.

- ^ a b Wieland Shields 2019, p. 84.

- ^ Hubbard-Morton, Alexandra (2002). Listening To Whales: What the Orcas Have Taught Us. Toronto: Random House. pp. 97–99. ISBN 9780307487544.

- ^ Safina 2015, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Wieland Shields 2019, p. 85.

- ^ Rehn, Nicola; Filatova, Olga A; Durban, John W; Foote, Andrew D (2011). "Cross-cultural and Cross-ecotype Production of a Killer Whale 'Excitement' Call Suggests Universality". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (1). Springer Nature Switzerland AG: 1–6. Bibcode:2011NW.....98....1R. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0732-5. PMID 21072496. S2CID 9927522.

- ^ White, Don (April 12, 1975). "Let's not lose our remaining killer whales". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database: 25 master tapes for Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Ford 1984, p. 287.

- ^ Ford 1984, p. ii.

- ^ a b c d e f Leiren-Young, Mark (2016). The Killer Whale Who Changed the World (epub ed.). Vancouver, B.C.: Greystone Books Ltd. pp. 113–114. ISBN 9781771641944.

- ^ Allgood, Fred (August 17, 1964). "Moby-Talk Draws Expert Here for 1st-Hand Study". Vancouver Sun. p. 2.

- ^ a b Schevill & Watkins 1966, p. 71.

- ^ Schevill, William E.; McBride, Arthur F. (1956). "Evidence for echolocation by cetaceans, (1953)". Deep Sea Research. 3 (2). Elsevier B.V.: 153–154. doi:10.1016/0146-6313(56)90096-X. ISSN 0146-6313.

- ^ a b c Schevill & Watkins 1966, p. 72.

- ^ Schevill & Watkins 1966, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Schevill & Watkins 1966, p. 73.

- ^ Ford 1984, p. 284.

- ^ "Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)". NOAA Fisheries: Office of Protected Resources. June 25, 2014. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014.

- ^ Clapperton, Jonathan (2019). "Whales and Whaling in Puget Sound Coast Salish History and Culture". RCC Perspectives (5): 99–104. ISSN 2190-5088. JSTOR 26850627.

- ^ a b c d e "Lummi's sacred obligation is to feed orcas, our relations under the waves". The Seattle Times. March 3, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Guernsey, Paul J.; Keeler, Kyle; Julius, Jeremiah 'Jay' (July 21, 2021). "How the Lummi Nation Revealed the Limits of Species and Habitats as Conservation Values in the Endangered Species Act: Healing as Indigenous Conservation". Ethics, Policy & Environment. 24 (3): 266–282. doi:10.1080/21550085.2021.1955605. ISSN 2155-0085. S2CID 238820693.

- ^ "'Our relatives under the water.' Lummi release salmon to ailing orcas". KUOW. April 12, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Lummi Nation asks NOAA for emergency intervention to aid Puget Sound orcas". www.kuow.org. May 22, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Baird, Robin William; Stacey, Pam Joyce (March 3, 1988). "Variation in saddle patch pigmentation in populations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) from British Columbia, Alaska, and Washington State" (PDF). Can. J. Zool. 66 (11): 2582–2585. doi:10.1139/z88-380. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Ford, Ellis & Balcomb 2000, p. 19.

- ^ "Species in the Spotlight: Southern Resident Killer Whales Priority Actions: 2021–2025" (pdf). NOAA Fisheries. USA.gov. April 21, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Noakes, Donald J, Richard J Beamish, and Michael J Kent. "On the decline of Pacific salmon and speculative links to salmon farming in British Columbia." Aquaculture. 183.3-4 (363): 386.

- ^ Naylor, R. L.; Goldburg, R. J.; Primavera, J. H.; Kautsky, N.; Beveridge, M. C.; Clay, J.; Folke, C.; Lubchenco, J.; Mooney, H.; Troell, M. (June 27, 2000). "Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies". Nature. 405 (6790): 1017–1024. Bibcode:2000Natur.405.1017N. doi:10.1038/35016500. hdl:10862/1737. PMID 10890435. S2CID 4411053.(subscription required)

- ^ Cullon, D.L., et al. 2009. Persistent organic pollutants in Chinook salmon (oncorynchus tshawytscha): implications for resident orca of British Columbia and adjacent waters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 28:148-161.

- ^ O'Neill, S, and J West. "Marine Distribution, Life History Traits, and the Accumulation of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Chinook Salmon from Puget Sound, Washington." Transactions of the American Fisheries Societies. 138.3 (2009): 616-32.

- ^ "Causes of Decline among Southern Resident Killer Whales". Center for Conservation Biology. University of Washington. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Ross, P.S, G.M Ellis, et al. "High PCB Concentrations in Free- Ranging Pacific Killer Whales, Orcinus orca: Effects of Age, Sex and Dietary Preference." Marine Pollution Bulletin. 40.6 (2000): 504–515

- ^ Wotkyns, Sue; Khatibi, Mehrdad (May 10, 2012). "Fisheries Impact". Tribes and Climate Change. Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals & Northern Arizona University. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015.

- ^ "The Dolphin Defender: The effects of PCBs". Nature. PBS. June 12, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ Buckman, AH, N Veldhoen, et al. "PCB-Associated Changes in mRNA Expression in Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) from the NE Pacific Ocean."ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY. 40.23 (2011): 10194-10202

- ^ a b Mishael, Mongillo, Teresa; Maria, Ylitalo, Gina; D., Rhodes, Linda; M., O'Neill, Sandra; Page, Noren, Dawn; Bradley, Hanson, M. (2016). "Exposure to a mixture of toxic chemicals : implications for the health of endangered southern resident killer whales". doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-135.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Boat Disturbance". Wild Whales. Vancouver Aquarium. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016.

- ^ Slaughter, Graham (December 9, 2011). "Whales, interrupted: How noise pollution from boats and sonar from ships hurt orcas". Canadian Geographic. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Jones, Katie (August 24, 2023). "Toki will always be remembered". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c "A brief history of the Southern Residents • Georgia Strait Alliance". Georgia Strait Alliance. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Olesiuk, Bigg & Ellis 1990, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Bigg, MacAskie & Ellis 1976, p. 12.

- ^ "Protect the environment/Right of nature". Earth Law Center. October 22, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Colby 2018, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Colby 2018, pp. 103–106.

- ^ "Griffin Adds Fifth Whale To Aquarium". The Seattle Times. March 6, 1967. p. 8.

- ^ Bigg et al. 1990, p. 400.

- ^ "Southern Resident Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)". NOAA Fisheries. June 3, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Puget Sound Partnership - Southern Resident Orca Task Force". www.psp.wa.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Task Force on Contaminates meeting notes, Aug 7 2018" (PDF). August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Task Force on Forage Fish meeting notes" (PDF). August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Mercado, Angely (December 8, 2022). "A City in Washington Wants to Give Orcas Their Own Version of Human Rights". Gizmodo. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "Government of Canada taking further action to protect Southern Resident Killer Whales". Newswire Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. October 31, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

General references[edit]

- Bigg, Michael A.; MacAskie, Ian B.; Ellis, Graeme (March 8, 1976). Abundance and movements of killer whales off eastern and southern Vancouver Island, with comments on management (Report). Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Quebec: Department of Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Arctic Biological Station.

- Bigg, M. A.; Olesiuk, P. F.; Ellis, G. M.; Ford, J. K. B.; Balcomb III, K. C. (1990). "Social Organization and Genealogy of Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in the Coastal Waters of British Columbia and Washington State". Report of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 12). Cambridge: 383–405. ISSN 0255-2760.

- Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190673116.

- Ford, John Kenneth Baker (1984). Call Traditions and Dialects of Killer Whales (Orcinus Orca) in British Columbia. Retrospective Theses and Dissertations, 1919-2007 (Thesis). University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0096602.

- Ford, John K.B.; Ellis, Graeme M.; Balcomb, Kenneth C. (2000). Killer Whales: the natural history and genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington (2nd ed.). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. ISBN 9780774808002.

- Olesiuk, P. F.; Bigg, M. A.; Ellis, G. M. (1990). "Life History and Population Dynamics of Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in the Coastal Waters of British Columbia and Washington State". Report of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 12). Cambridge: 209–244. ISSN 0255-2760.

- Safina, Carl (2015). Beyond Words: what animals think and feel. New York NY USA: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 9780805098884.

- Schevill, William; Watkins, William (Summer 1966). "Sound Structure and Directionality in Orcinus (killer whale)". Zoologica. 51 (2). New York Zoological Society: 71–76.

- Wieland Shields, Monika (2019). Endangered Orcas: the story of the Southern Residents. Friday Harbor, Washington, USA: Orca Watcher. ISBN 9781733693400.