South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Charleston, South Carolina |

| Locale | South Carolina |

| Dates of operation | 1827–1843 |

| Successor | South Carolina Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 5 ft (1,524 mm) |

The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company was a railroad in South Carolina that operated independently from 1830 to 1844. One of the first railroads in North America to be chartered and constructed, it provided the first steam-powered, scheduled passenger train service in the United States.[1]

Chartered under act of the South Carolina General Assembly of December 19, 1827, the company operated its first 6-mile (9.7 km) line west from Charleston, South Carolina in 1830. The railroad ran scheduled steam service over its 136-mile (219 km) line from Charleston, South Carolina, to Hamburg, South Carolina, beginning in 1833.[2] Some sources referred to the railroad informally as the Charleston and Hamburg Railroad, a reference to its end points, but that was never its legal name. In 1839, The Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company,[3] which had built no track of its own, gained stock control of The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, which continued to operate under that name. In 1844, The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company merged with the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company. The merged company changed its name to South Carolina Railroad Company under an act of the South Carolina legislature dated December 19, 1843.

History[edit]

With the advent of cotton cultivation in the early 19th century, the relatively remote South Carolina upcountry enjoyed a vast expansion in the value of its agricultural produce. Overland transport by wagon was slow and expensive, so this produce tended to go to Augusta, Georgia, then down the Savannah River to the seaport at Savannah, Georgia. The SCC&RR Company was chartered on December 19, 1827 (amended January 30, 1828)[4] to divert this commerce to Charleston by means of connections to Columbia, Camden and Hamburg. Despite its novelty the project was pursued by its Charleston leaders with aggressive method, public demonstrations encouraging support for the daring concept of a steam-driven railroad. Under William Aiken as the first president, six miles (10 km) of line were completed at Charleston in 1830. However, construction was delayed and expenses increased by a shortage of labor, due to the high death rate of slaves leading to a reluctance to lease slave labor to the project by plantation owners. Messrs. Gray & Co., the principal firm of contractors, turned to importing a large number of white laborers from the North and from Europe.[2] The first run over the entire 136-mile (219 km) line was celebrated in October 1833.

Elias Horry had become president of the company in 1831, and was responsible for building what was then the longest railway in the world.[5]

The line was a commercial success despite price competition against riverborne traffic and later railroad projects in Georgia. Its initial cost of $951,148[6] was doubled by early way improvements, at that price still quite economical. This satisfying position blew up in the course of an overly ambitious overmountain expansion under the name of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad. It never reached the Ohio River at Cincinnati, although it reached Columbia, South Carolina in 1840, Camden, South Carolina in 1848 and Atlanta, Georgia in 1853. The SCC&RR successfully weathered the Panic of 1837 and overhanging debt from the busted LC&CRR, but not without a retrenchment that continued through the next decade. South Carolina legislators merged the two companies' charters in 1844.

Early engineering[edit]

The SCC&RR was fortunate in its chief engineer, Horatio Allen, who had already toured English railroads, and drove the Stourbridge Lion on its first and only run in America. Allen argued successfully before the SCC&RR directors for immediate adoption of steam locomotion, stating that the power of horses was known and would never increase, but the future power of locomotives was beyond imagination. The first locomotive was the Best Friend of Charleston of 1830; by 1834 the line had purchased a total of 15 locomotives and scheduled one daily run in each direction.

The way consisted of flat strap iron fastened to continuous timber sills. Much of the way passed easily through South Carolina's monotonously flat Pine Barrens. Elsewhere, the track was elevated – frequently over long distances – on timber pilings. A drop of 180 ft (55 m) over a 3,800 ft (1,200 m) run into Horse Creek Valley required an inclined plane, with a steam-powered winch later replaced by a locomotive used as a counterweight. Delays at this archaic bottleneck brought about the railroad town of Aiken, South Carolina, as a stopover place.

The line was built with 16 equally spaced turnouts each with a water pump and timber shed. A maintenance station responsible for perhaps eight miles (13 km) of track was based at each turnout. The station overseer surveyed half of that track daily, and effected minor repairs such as making secure loose bars of iron, punching down protruding spikeheads, chamfering wheel flange rubs off the rails, ramming earth around the piles, and so on. The overseer was also responsible for maintaining adequate supplies of water and timber at the station, and for calling on the Superintending Engineer for nonroutine derangements.

Timber pilings had allowed the SCC&RR to build their line quickly and cheaply, especially in comparison with northern lines such as the Baltimore and Ohio that tended to overbuild. Nevertheless, by 1834 the pilings began to rot at the ground line, and were supplanted by earthen embankments made by dumping dirt over the side (encasing and preserving some of the longleaf pine structures to this day). Beginning in 1836 the flat strap rails were replaced with "T" rails.

Wood rot was an early maintenance evil. By 1841 a surface treatment called Kyanizing was found to be helpful, but used a toxic mercury compound for wood preservation — shortly thereafter the cheaper (and less toxic) Earlizing with copper and iron sulphates was adopted. When new longer routes made night travel necessary, passenger faced risks from collisions. South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company experimented with a pine log fire on a flatcar covered in sand to provide light before inexpensive kerosene for lamps was invented.[7]

Novel and clumsily designed locomotives were a great expense with generally half of the large fleet laid up for repairs, modification or breaking up. These early machines suffered from slightness in the drive wheels, axles and valve gear, and from unequal distribution of weight, a serious problem given the questionable track they ran on. Inside actions were eventually converted to outside. The early eight-wheeled locomotives shared these problems along with overly weak frames, but otherwise were appreciated for greater power and less injury to the road. With limited facilities in an agricultural economy, all of these shortcoming resulted in long outages. Through 1834, locomotives had been purchased from six different suppliers.

The original line generally paralleled U.S. Route 78 and remained in service until the 1980s. The downtowns of many railroad towns such as Warrenton, Williston and Blackville are still marked by railroad esplanades frequently with elevated causeways.

Branches[edit]

- Columbia

In accordance with the original charter, a 66.3-mile (106.7 km) line from Branchville to Columbia was built in 1840 and opened in 1842.[4]

Merger[edit]

In 1844, The Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company and The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company were merged under an act of the South Carolina General Assembly of December 19, 1843 as the South Carolina Railroad Company.[4]

National Historic Landmark in Charleston[edit]

William Aiken House and Associated Railroad Structures is a historic district in Charleston, South Carolina, that contains structures of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company and the home of the company's founder, William Aiken. These structures are considered "nationally significant" in relation to the history of the development of the railroad industry in the United States.[8] The South Carolina Department of Archives and History states that the structures in this district "represent the best extant collection of antebellum railroad structures illustrating the development of an early railroad terminal facility." [8] The railroad company with which they are associated was the first to use steam from the beginning of its operations, use an American-made locomotive, and carry U.S. mail.[8][9] When it began operation in 1833 it had the greatest length of track in the world under single management.[9]

The district was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1963.[9][10] Contributing structures in the district include:[9]

- William Aiken House, built in 1807. An octagonal wing added in 1831 but damaged in 1886 earthquake, and certain woodwork was removed in 1931. A servants wing is unchanged.

- A coach house at the back of gardens on the William Aiken House property

- Camden Depot, a railroad depot

- Deans Warehouse, built in 1856

- South Carolina Railroad Warehouse

- Tower Passenger Depot

- Line Street Car and Carpenter Shops

- Railroad Right-of-Way

- "Best Friend of Charleston" Replica, a replica of the first American-made steam locomotive

Notes[edit]

- ^ Mauldin, G. E. (1928). "South Carolina Canal and Rail Road". The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin (17): 70–80. ISSN 0033-8842. JSTOR 43504505.

- ^ a b Ulrich Bonnell Phillips (1908). Transportation in the Ante-bellum South: An Economic Analysis. Ulrich Bonnell Phillips. pp. 148–153.

- ^ "The" was part of the corporate name of both this company and The South Carolina Rail Road Company. See Southern Ry. Co., Volume 37, Interstate Commerce Commission Valuation Reports, November 6, 1931, p. 521. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1932.

- ^ a b c Southern Ry. Co., Volume 37, Interstate Commerce Commission Valuation Reports, November 6, 1931, p. 521. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1932.

- ^ Smith, Alice R. Huger; Smith, D.E. Huger (2007). The Dwelling Houses of Charleston. Charleston: The History Press. p. 60. ISBN 9781596292611.

- ^ A Short History of South Carolina, 1520–1948, David Duncan Wallace, page 377

- ^ Christian Wolmar (2 March 2010). Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World. PublicAffairs. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-58648-851-2.

- ^ a b c "William Aiken House and Associated Railroad Structures (456 King St., Charleston)". National Register Properties in South Carolina listing. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ a b c d James Dillon and Cecil McKithan (May 12, 1981). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: William Aiken House and Associated Railroad Structures" (pdf). National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying seven photos, from 1961 and 1975 (32 KB) - ^ "William Aiken House and Associated Railroad Structures". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

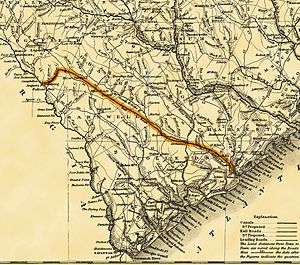

This map depicts a certain section of railroad tracks in the wrong location. It went through Branchville to St. George and so on from the north side of the Edisto River.

https://www.waymarking.com/gallery/image.aspx?f=1&guid=6a0f677c-7dbd-4f1a-a7a3-210d69d29ac6

References[edit]

- Southern Ry. Co., Volume 37, Interstate Commerce Commission Valuation Reports, November 6, 1931, pp. 521, 524. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1932.

- Phillips, Ulrich B. (1908). A History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860. Columbia University Press and reprints. pp.132–220

- Brown, William H. (1871). The History of the First Locomotives In America. D. Appleton and Company and reprints.

- Derrick, Samuel M. (1933). Centennial History of South Carolina Railroad. State Publishing Company, Columbia, SC.

- Bianculli, Anthony J. (2002). Trains and Technology: The American Railroad in the Nineteenth Century. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-729-2. pp. 89–94

External links[edit]

- The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company

- 1833 South Carolina Transportation Map

- 1880 South Carolina Railroad Map

- Branchville – The First Railroad Junction

- William Aiken House and Associated Railroad Structures, Charleston County (456 King St., Charleston), including 13 photos, at South Carolina Department of Archives and History

All of the following Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) records are filed under Charleston, Charleston County, SC:

- HABS No. SC-373-A, "South Carolina Railroad-Southern Railway Company, 456 King Street", 31 photos, 2 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HABS No. SC-373-D, "South Carolina Railroad-Southern Railway Company, Carriage House, 456 King Street", 2 photos, 2 photo caption pages

- HABS No. SC-373-B, "South Carolina Railroad-Southern Railway Company, Camden Depot, Anne Street", 4 photos, 2 photo caption pages

- HABS No. SC-373-C, "South Carolina Railroad-Southern Railway Company, Warehouse, 42 John Street", 1 photo, 1 photo caption page

- Defunct South Carolina railroads

- Predecessors of the Southern Railway (U.S.)

- Railway companies established in 1827

- Railway companies disestablished in 1844

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Historic American Buildings Survey in South Carolina

- Railway lines opened in 1830

- 5 ft gauge railways in the United States

- 1827 establishments in South Carolina

- American companies established in 1827