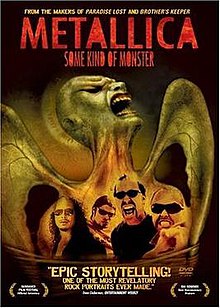

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster

| Metallica: Some Kind of Monster | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Joe Berlinger Bruce Sinofsky |

| Produced by | Joe Berlinger Bruce Sinofsky |

| Starring | James Hetfield Lars Ulrich Kirk Hammett Robert Trujillo |

| Cinematography | Robert Richman |

| Edited by | Doug Abel M. Watanabe Milmore |

Production companies | Third Eye Motion Picture @Radical.Media |

| Distributed by | IFC Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2,009,087[1] |

Metallica: Some Kind of Monster is a 2004 American documentary film about American heavy metal band Metallica. The film follows the band from 2001 to 2003, a turbulent period in the band's history which included the production of their 2003 album St. Anger, frontman James Hetfield entering into rehab for alcoholism and the departure of bassist Jason Newsted as well as the hiring of his replacement Robert Trujillo. The title of the film shares its name with the song of the same name from St. Anger.

Plot[edit]

In April 2001, heavy metal band Metallica is at a crossroads. Their lawsuit against file sharing service Napster has caused a fan backlash, longtime bassist Jason Newsted has quit the group, and relations between the band members are at an all-time low. They are working with "performance enhancement coach" Phil Towle to deal with their growing tensions. Newsted says that singer and guitarist James Hetfield would not let him pursue his side project, Echobrain, and calls the band's decision to bring in a therapist "really fucking lame and weak".

Metallica begins work on a new studio album, using an empty barracks at the Presidio of San Francisco as a recording studio and drafting Bob Rock, their longtime record producer, to play bass on the recordings. The process is more collaborative than usual; songs are written from scratch in the studio, the members and Rock contributing equally to music and lyrics. "Some Kind of Monster" and "My World" result from these sessions. Six weeks in, Hetfield and drummer Lars Ulrich have an argument during a recording session and Hetfield storms out. He enters drug rehabilitation to undergo treatment for alcoholism and other addictions, putting the album on hold. Ulrich previews some of the new recordings for his father, who says the new material "doesn't cut it".

After three months without Hetfield, the band's future is in doubt. Ulrich, Rock, and guitarist Kirk Hammett continue their sessions with Towle. Hammett, who has battled his own addictions in the past, retreats to his northern California ranch, hopeful that things will work out. As part of the therapy process, Ulrich meets with Metallica's original lead guitarist, Dave Mustaine, who was fired from the band in 1983. Mustaine says that despite the success of his band Megadeth, he has always felt second best to Metallica and carries a deep resentment toward them. Ulrich, Hammett, and Rock attend an Echobrain concert, after which Ulrich laments his inability to keep his own band together. As Hetfield's absence extends past six months, Metallica gives up their lease at the Presidio.

In April 2002, Hetfield exits rehab and returns to the band, who resume recording at their new studio, "HQ", developing the song "Frantic". As part of his recovery, Hetfield may only work for four hours each day, and he asks that the others not work on, listen to, or even discuss recorded material without him present. Frustrated by these restrictions, Ulrich accuses Hetfield of being too controlling, culminating in an intense band meeting in which Ulrich vents his frustrations. The relationship between the two founding Metallica members becomes further strained while working on "The Unnamed Feeling". Hetfield reflects that his need to control the band stems from a fear of abandonment originating from his childhood. Hammett, who sees himself as a calm counterpoint to his bandmates' warring egos, is upset by their insistence on excluding guitar solos from the album.

The band members bristle against their management's insistence that they record a promo for a radio contest, and their resentment informs the song "Sweet Amber". Their productivity increases, and Ulrich works his feelings about the Napster lawsuit into lyrics for "Shoot Me Again". While deciding which songs will make the album, the members feel that their chemistry has improved. They begin to reject Towle's methods and feel that he has insinuated himself too closely into the band. When they propose curtailing their relationship with him, Towle becomes defensive.

Metallica is chosen to be recognized and perform at the upcoming MTV Icon tribute show, accelerating their search for a new bassist. After auditioning several bassists from other bands, they select Robert Trujillo, whose abilities impress them and whose finger-style playing reminds them of their early bassist, Cliff Burton, who died in a tour bus accident in 1986. They choose St. Anger as the title for their new album, and film the music video for the title track at San Quentin State Prison. As they prepare to go on tour for the first time in three years, Ulrich says they have "proven that you can make aggressive music without negative energy." The film concludes with a montage of Metallica performing "Frantic" to stadium crowds on their summer 2003 tours, and notes that St. Anger debuted at no. 1 in 30 countries.

Background[edit]

Documentary filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky had begun a professional relationship with Metallica while making their 1996 film Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills, about the West Memphis Three.[2] Moved by the story of the West Memphis Three, Metallica, who normally did not allow their music to be used in films, allowed Berlinger and Sinofsky to use their songs in Paradise Lost for free.[2][3] The band and the directors kept in touch, discussing the possibility of working on a larger project together.[2] Berlinger split from Sinofsky to direct Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000), which was critically panned and made little money.[2] After this experience, he contacted Sinofsky and Metallica about revisiting their plans for a film.[2]

The year 2000 had been, in the words of bassist Jason Newsted, "possibly the highest-profile year for Metallica ever."[4] The band had released the live album S&M in late 1999, then played a New Year's Eve show with Ted Nugent, Sevendust, and Kid Rock.[4][5] In February they won a Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance for their cover version of "Whiskey in the Jar" (from their 1998 covers album Garage Inc.).[5] The following month, they filed a highly-publicized lawsuit against file sharing service Napster.[4][6] In May they released the new single "I Disappear" from the Mission: Impossible 2 soundtrack; they performed the song at the 2000 MTV Movie Awards in June, and its music video was nominated in five categories at the 2000 MTV Video Music Awards that September.[4][6] Metallica spent June through August on the Summer Sanitarium Tour, playing 20 shows with Korn, Kid Rock, Powerman 5000, and System of a Down.[4] During the tour, singer and rhythm guitarist James Hetfield was injured in a jet ski accident and had to miss three shows.[4]

The band took a break beginning that fall, which turned into the longest hiatus from touring and recording they had ever taken.[4] In November 2000, the members were interviewed separately for a feature in Playboy, their responses illustrating a growing sense of discontent within the group.[2][4] Interviewer Rob Tannenbaum wrote that "I've never seen a band so quarrelsome and fractious [...] genuine tension was evident in these interviews—the last ever to be conducted with this Metallica lineup—because they shared one trait: Each talked about his need for solitude. Paradoxically, this is a band of loners, and the conflict between unity and individuality was pretty clear."[4] In particular, Newsted, who needed time off to recover from neck and back injuries sustained from years of onstage headbanging, was upset that Hetfield would not permit him to release an album by his side project, Echobrain.[4][7] Hetfield believed that doing so would "take away from the strength of Metallica", while lead guitarist Kirk Hammett and drummer Lars Ulrich separately opined that Newsted should be able to release the album.[4] Newsted also wanted to play a greater creative role in Metallica, whose direction was dominated by Hetfield and Ulrich, and felt that the band had lost its focus and was spending too much time on matters such as the Napster lawsuit.[7] "We spent more time in f---in' court last year than we did playing our instruments", he said in 2001.[7]

In an effort to keep the band together, their management company, Q Prime, connected them with "performance enhancement coach" Phil Towle.[2] Though not a trained psychologist or psychiatrist, Towle, a former Chicago gang counselor, had worked with the St. Louis Rams during the 1999–2000 NFL playoffs (which concluded with the Rams winning Super Bowl XXXIV), and had unsuccessfully tried to keep another of Q Prime's clients, Rage Against the Machine, from breaking up.[2] After just one session with Towle, Newsted, who had been with Metallica since 1986, quit the group following a 91⁄2 hour band meeting.[2][4] Announcing his resignation on January 17, 2001, he cited "private and personal reasons, and the physical damage I have done to myself over the years while playing the music that I love".[8] The remaining members stated that they still planned to start work on a new studio album that spring, and would continue with a new bassist.[8] In a later interview, Newsted stated his distaste for the idea of Metallica going through group therapy: "Something that's really important to note — and this isn't pointed at anyone — is something I knew long before I met James Hetfield or anyone else: Certain people are made to be opened up and exposed. Certain people are not. I'll leave it at that."[2]

Production[edit]

When Berlinger and Sinofsky began filming Metallica in April 2001, the band was mired in turmoil.[2][9] Still without a bassist, the members were not getting along and were struggling creatively while trying to make a record.[2] The original scope of the filmmakers' project was to film the band in the recording studio and produce a pair of 60-minute infomercials to be broadcast on late-night television to promote the forthcoming album.[2] Things became more complicated when, three months into filming, Hetfield abruptly left the recording sessions and checked himself into drug rehabilitation to undergo treatment for alcoholism and other addictions, and the band suspended all activities including work on the album.[2][9] Hetfield remained in rehabilitation until that December, and did not return to the studio until April 2002.[9] During this time, the filmmakers continued to follow Hammett and Ulrich, including their sessions with Towle.[2] "Lars felt the therapy sessions were actually enabled by the presence of the cameras", said Berlinger; "He felt the cameras forced them to be honest."[2] Ultimately, they filmed Metallica for 715 days.[2]

When Hetfield returned from rehabilitation, he was uncertain whether filming should continue.[10] Berlinger and Sinofsky showed the band 20 minutes of scenes in progress, which helped convince them to continue with the project.[10] As filming went on, Metallica's label, Elektra Records, grew concerned over the project's escalating cost and considered turning it into a reality television show.[2] By that point, the band and filmmakers envisioned the documentary as a theatrical release.[2] Desiring complete control over it, Metallica bought the rights to the film from Elektra for $4.3 million.[2] Hetfield and Hammett disliked a scene in which Ulrich and his wife sell pieces from their art collection at a Christie's auction for $13.4 million.[2] Hetfield called the scene "downright embarrassing" and wanted it removed, but Ulrich insisted on its inclusion, saying that his passion for art was an essential aspect of his personality and that "If you're going to paint a portrait of the people in Metallica, that has to play a role, because that is who I am."[2]

Reception and legacy[edit]

The film holds an 89% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with the consensus that it is a "Fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how Metallica survives one of their more turbulent periods."[11] Metacritic reported the film had an average score of 74 out of 100, based on 32 reviews. A fragment of the summary says "...this documentary provides a fascinating, in-depth portrait of the most successful heavy metal band of all time...".

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave it an "A", writing that it is "one of the most revelatory rock portraits ever made".[12]

Accolades[edit]

The film won the Independent Spirit Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2005.[13]

Band reactions[edit]

Lars Ulrich reflected on the production, saying: “We were at a crossroads. We had been really good at being able to compartmentalize a lot of this stuff. Suppress it with drinking or other extravagances. This was the first time we had to talk to each other, get to know each other and work stuff out. The cameras were there catching all of it.”[14]

The producers requested Dave Mustaine's approval to include footage of his 2001 meeting with Ulrich. Although Mustaine denied the request, he had earlier signed a release form giving the band and the producers the right to use the footage. Mustaine later claimed that this marked "the final betrayal" and that he has now given up hope of ever fully reconciling with his former bandmates.[15] Although he received a measure of satisfaction at being included and acknowledged in the film as Metallica's original guitarist, Mustaine felt his interview footage was edited to portray him in a "less than flattering" manner.[16] Responding to Mustaine's criticism, Ulrich said, "So put these three facts down, he was in our band for a year. He never played on a Metallica record [official release], and it was 22 years ago. It's pretty absurd that it still can be that big a deal."[17]

Mustaine eventually reconciled with Metallica. On June 16, 2010, Megadeth and Metallica played the first of what would end up being several shows with Slayer and Anthrax as the "big four of thrash metal", their first concert being in front of over 80,000 fans in Warsaw, Poland. The night before, the band members had a collective dinner described as "laid-back" and "enjoyable" by Mustaine, which began with Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo hugging Mustaine.

The "Big Four" collective played their last concert on September 14, 2011, in New York City's Yankee Stadium. In February 2016, Mustaine reiterated that he felt open to more concerts and was not opposed to working with Metallica and others again, with only issues of timing and scheduling being in the way.[18]

Metallica re-released the film, including a bonus 25-minute documentary, in 2014 to celebrate its 10th anniversary.[19]

Bass auditionees[edit]

- Danny Lohner of Nine Inch Nails

- Twiggy Ramirez (Jeordie White) of Marilyn Manson and A Perfect Circle

- Pepper Keenan of Corrosion of Conformity

- Scott Reeder of Kyuss

- Chris Wyse of The Cult

- Eric Avery of Jane's Addiction

All appear while auditioning for Metallica's vacant bassist position. Robert Trujillo was eventually selected.

Charts[edit]

| Chart (2005) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian (Flanders) Music DVDs Chart[20] | 1 |

| Belgian (Wallonia) Music DVDs Chart[21] | 1 |

| Finnish Music DVDs Chart[22] | 4 |

| Irish Music DVDs Chart[23] | 1 |

| Italian Music DVDs Chart[24] | 5 |

| New Zealand Music DVDs Chart[25] | 1 |

| Norwegian Music DVDs Chart[26] | 1 |

| Swedish Music DVDs Chart[27] | 1 |

References[edit]

- ^ "Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Klosterman, Chuck (June 20, 2004). "Band on the Couch". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Downey, Ryan J. (February 3, 2010). "Paradise Lost Team Plans Two More West Memphis Three Documentaries". mtv.com. MTV. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tannenbaum, Rob (April 2001). "Metallica: Playboy Interview". playboy.com. Playboy. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Metallica Timeline: 1999". mtv.com. MTV. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Metallica Timeline: 2000". mtv.com. MTV. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Wiederhorn, Jon (October 10, 2001). "Jason Newsted Gets Busy After Metallica". mtv.com. MTV. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Basham, David (January 17, 2001). "Bassist Jason Newsted Leaves Metallica". mtv.com. MTV. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Metallica Timeline: 2001". mtv.com. MTV. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Berlinger, Joe; Sinofsky, Bruce (2005). "Should the Filming Continue?". Metallica: Some Kind of Monster (Bonus Features) (DVD). Hollywood, California: Paramount Pictures. 88637.

- ^ "Metallica: Some Kind of Monster". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 8, 2004). "Metallica: Some Kind of Monster; Genre: Documentary; Director: Joe Berlinger, Bruce Sinofsky..." (movie review). Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ^ Blabbermouth (February 26, 2005). "METALLICA's 'Some Kind Of Monster' Named Best Documentary At INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS". BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Reilly, Travis (December 23, 2014). "Metallica's Lars Ulrich on How Rock Doc 'Some Kind of Monster' Kept Band From 'Derailing'". Thewrap.com. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ "Dave Mustaine slams Metallica over 'Some Kind of Monster' movie". Blabbermouth.net. June 4, 2004. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2007.

- ^ Doe, Bernard (February 11, 2005). "Life after 'Deth – The outspoken Dave Mustaine looks ahead to a solo career as he calls time on Megadeth". Rockdetector.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ "Lars Ulrich slams Dave Mustaine for his 'Pathetic' Metallica-bashing". Blabbermouth.net. January 10, 2006. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2007.

- ^ "Megadeth's Dave Mustaine: What It Would Take For Another 'Big Four' Concert To Happen". Blabbermouth.net. February 28, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham. "Metallica Plan Re-Release of 'Some Kind of Monster' Film". Loudwire. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ "Ultratop 10 Muziek-DVD". Ultratop (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Ultratop 10 DVD Musicaux". Ultratop (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Suomen Virallinen Lista – Musiikki DVD:t 13/2005". Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland (in Finnish). Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Irish Charts – Singles, Albums & Compilations". IRMA. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Classifiche: Archivio – DVD Musicali". FIMI (in Italian). Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Top 10 Music DVDs". RIANZ. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "DVD Audio Uke 5,2005". VG-lista (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ "Sveriges Officiella Topplista". Sverigetopplistan (in Swedish). Retrieved March 5, 2013. Search for Metallica Some Kind of Monster and click Sök.