Rusk County, Wisconsin

Rusk County | |

|---|---|

Ladysmith Carnegie Library, designed by Claude and Starck. It is now operated as a bed and breakfast inn. | |

Location within the U.S. state of Wisconsin | |

Wisconsin's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 45°29′N 91°08′W / 45.48°N 91.14°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1901 |

| Named for | Jeremiah McLain Rusk |

| Seat | Ladysmith |

| Largest city | Ladysmith |

| Area | |

| • Total | 931 sq mi (2,410 km2) |

| • Land | 914 sq mi (2,370 km2) |

| • Water | 17 sq mi (40 km2) 1.9% |

| Population | |

| • Total | 14,188 |

| • Density | 15.5/sq mi (6.0/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Website | www |

Rusk County is a county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,188.[1] Its county seat is Ladysmith.[2] The Chippewa and Flambeau rivers and their tributaries flow through the county. The land ranges from corn/soybean farms and dairy farms to lakes rimmed with vacation homes to hiking trails through the Blue Hills.

History[edit]

The forested wilderness that would become Rusk County was home to different Indian nations over the years. Some used the rivers to pass through, some camped, some buried their dead there. The first recorded Europeans in the county were Father Louis Hennepin and his company, who canoed up the Chippewa in 1680 when the area was part of New France, on their way to Lac Courte Oreilles and Madeline Island. In 1790 Lakota warriors came up the Chippewa to attack the Ojibwe, but they were defeated, leaving the Ojibwe in control through the fur trade era.[3]: 6

The first loggers and settlers came up the Chippewa River from the south, entering what would become Rusk County north of modern Holcombe, where the Flambeau River joins the Chippewa.[3]: 6 An Indian settlement lay on the bank of the Chippewa near where St. Francis of Assisi Mission Church stands.[4]

European-American settlement began near that Indian village in 1847, when Adolph La Ronge and his wife came from Canada. By the 1860s the Daniel Shaw Lumber Company had a farm two miles west (across from modern Flater's Resort) to support their operations.[3]: 6

Loggers initially went up the rivers and cut the choicest pine in winter, then drove masses of logs down to sawmills in Chippewa Falls and Eau Claire on the spring and early summer floods. At first they poled supplies up the rivers in bateaux, but later cut "tote roads" to haul supplies with oxen and horses to their remote logging camps.

One of these early tote roads was the Chippewa Trail, which followed west of the Chippewa from the south end of the county to the north end near Exeland, and beyond. By 1880 the Chippewa Trail was developed into a stage road, with a horse-drawn stage running up it one day and back down the next. Stopping places (rough inns) were located about every five miles, where lumberjacks could rest and carouse on their way to and from the camps.[3]: 6–7 [5] An 1888 map of Chippewa County shows more roads, including one following the west side of the Flambeau from Shaw's farm to Flambeau Falls (Ladysmith).[6]

Railroads reached the area in 1884. The Mississippi River Logging Company brought in a locomotive, cars and rails by sleigh from Bloomer to start a logging railroad. Weyerhaueser's company had tried driving logs down the streams from the Potato Lake and Soft Maple areas, but the streams proved too small, so they laid track and hauled logs to Big Bend, then rolled them into the Chippewa. As the timber in that area was cut off, this railroad, named the Chippewa River and Menomonie Railroad, shifted operations, moving its rails north of Bruce.[7][8]: 26–28

That same year the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railroad (the Soo Line) started building its railroad across the area, aiming to connect the grain of the Twin Cities with the shipping at Sault Ste. Marie. The two railroads met west of Bruce at a place called Apollonia. In the 1890s the CR&M had shops and an engine house there and Apollonia grew to 350 people - the largest town at that time in the current bounds of Rusk County. The CR&M was notable for the huge wooden trestles it built near Star Lake and Deer Lake.[8]: 28–30

The Soo Line continued east in 1884 and 1885, creating other stations which would develop as the towns of Weyerhaeuser, Bruce, Warner (now Ladysmith), Deer Tail (now Tony), Miller's Siding (now Glen Flora), Ingram and Hawkins. This new railroad provided a way to get lumber out to markets. This was particularly helpful when logging turned from pine to hardwoods which didn't float as well. Many of these little towns along the Soo Line had sawmills, and some of those sawmills were fed by their own little logging railroads, reaching out into the forests.[3]: 7–8

Rusk County was established in 1901 when the Wisconsin legislature split off the northern half of what had been Chippewa County into a new Gates County. It started with that name because Milwaukee land speculator (and major land-holder in the county) James L. Gates said he would donate $1000 to the new county if it was named Gates. When Gates didn't come up with the money, the state legislature renamed the county Rusk in 1905[3]: 5 in honor of Jeremiah M. Rusk, governor of Wisconsin and the first U.S. Secretary of Agriculture.[9] The 1901 legislation also designated Corbett (now Ladysmith) as the county seat, which was challenged by other towns all the way to the state supreme court.[3]: 7

Around 1905 the Wisconsin Central Railroad built another rail line through the county, heading northwest from Chicago's direction toward Superior, and crossing the Soo Line at Ladysmith. In 1907, dedicated passenger trains began passing through.[3]: 7 The stations along this line spawned another string of hamlets: Sheldon, Conrath, Crane and Murry.[10]

The area's economy was evolving. The peak of pine log drives on the Chippewa had been around 1885 and they ended around 1906. Hardwood lumbering started in earnest around 1900 and peaked from 1905 to 1915, then began to decline.[7] With the decline of timber came uncertainty about the way forward, which led to schemes for mining, large-scale ranching, and manufacturing that came to nothing.[3]: 9 The paper mill started in Ladysmith, which did succeed.[3]: 81 The Big Falls Dam was built around 1920 to generate electricity,[3]: 14 and the Thornapple, Ladysmith and Port Arthur dams were converted from pulp-grinding to electricity-generating later.[3]: 346

All along, the lumber companies and their proxy land companies had been selling cut-over parcels to settler-farmers. The farmers grazed cattle, grew potatoes and rutabagas among the stumps, and gradually cleared the land with fire, dynamite and plows, eventually scratching out 40- and 80-acre family farms.[7] As more land was logged, more of the county turned to farms. The sawmill towns shifted to serving surrounding farms with stores, creameries, and feed mills.

During the Great Depression, times were tough in Rusk County. Banks failed at Weyerhaeuser,[3]: 75 Tony, Glen Flora, and Ingram.[3]: 21 Cheese factories failed.[3]: 75 But that was also the period when Jump River Electric, supported by the New Deal Rural Electric Administration, ran electricity to farms and homes in the country.[3]: 77–78

And a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was established in Rusk County. It employed many young men from Chicago and other cities, along with a few locals. The camp was started in June 1933 in the town of Murry in the Blue Hills, then moved in November to a site in Cedar Rapids north of Glen Flora. The men fought fires, built roads, supported fire towers, and planted trees. When the U.S. entered WWII, some of the CCCs enlisted or were drafted, and CCC Camp Rusk shortly disbanded.[3]: 10–11

Rusk County's first rural schools had been established at least by 1891 - the Bear Lake school opened then.[3]: 57 Those first schools were one-room, typically with one teacher for six grades. Ladysmith had a school by 1905.[3]: 56 Rusk County Normal School opened in Ladysmith in 1907, and by the time it closed in 1948 it had trained 719 qualified teachers.[3]: 63 Rusk County had 125 rural schools at one time.

After the Depression, rural population declined and farms merged. Rural schools too merged, until decent roads and busing allowed them to consolidate with larger graded town schools like Weyerhaeuser and Tony; consolidation of schools was completed around 1960.[3]: 61 The Hawkins school district joined Ladysmith in 1966,[3]: 56 then switched to the Flambeau district in 2009.[11]

The private Mount Senario College served the area in various forms from around 1962 to 2002.[12]

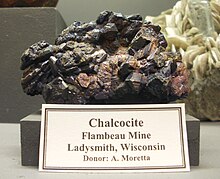

In the 1990s the Flambeau Mine was an open pit mine near the Flambeau River a mile south of Ladysmith, which produced copper, gold and silver. Mining so near the Flambeau River was controversial, with an initial plan blocked by the local zoning committee. Kennecott came back with a less risky proposal in 1987 and it was approved.

The mine operated from 1991 to 1999, excavating a pit 2,600 feet long and 220 feet deep, and producing 181,000 tons of copper, 334,000 ounces of gold, and 3.3 million ounces of silver. In the reclamation phase, the pit was back-filled and planted with native plants. It now offers walking trails open to the public.[13]

Over the years, sawmills and cheese factories in the smaller towns have closed, but other industries have grown. The largest employers in the county are now Weather Shield in Ladysmith, Jeld-Wen in Hawkins, Rusk County administration, the school districts, Wal-Mart, Artisans, the medical center in Ladysmith, and Rand Trucking.[14]

Geography[edit]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has an area of 931 square miles (2,410 km2), of which 914 square miles (2,370 km2) is land and 17 square miles (44 km2) (1.9%) is water.[15]

Adjacent counties[edit]

- Washburn County - northwest

- Sawyer County - north

- Price County - east

- Taylor County - southeast

- Chippewa County - south

- Barron County - west

Major highways[edit]

Railroads[edit]

Buses[edit]

Airport[edit]

- KRCX - Rusk County Airport serves the county and surrounding communities.

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 11,160 | — | |

| 1920 | 16,403 | 47.0% | |

| 1930 | 16,081 | −2.0% | |

| 1940 | 17,737 | 10.3% | |

| 1950 | 16,790 | −5.3% | |

| 1960 | 14,794 | −11.9% | |

| 1970 | 14,238 | −3.8% | |

| 1980 | 15,589 | 9.5% | |

| 1990 | 15,079 | −3.3% | |

| 2000 | 15,347 | 1.8% | |

| 2010 | 14,755 | −3.9% | |

| 2020 | 14,188 | −3.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] 1790–1960[17] 1900–1990[18] 1990–2000[19] 2010[20] 2020[1] | |||

2020 census[edit]

As of the census of 2020,[1] the population was 14,188. The population density was 15.5 people per square mile (6.0 people/km2). There were 8,560 housing units at an average density of 9.4 units per square mile (3.6 units/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 94.2% White, 0.5% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 0.3% Black or African American, 0.6% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 1.8% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2000 census[edit]

As of the census[22] of 2000, there were 15,347 people, 6,095 households, and 4,156 families residing in the county. The population density was 17 people per square mile (6.6 people/km2). There were 7,609 housing units at an average density of 8 units per square mile (3.1 units/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 97.69% White, 0.51% Black or African American, 0.42% Native American, 0.26% Asian, 0.10% Pacific Islander, 0.35% from other races, and 0.66% from two or more races. 0.76% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 32.7% were of German, 13.6% Polish, 9.0% Norwegian, 6.8% Irish, 6.2% American and 5.6% English ancestry.

There were 6,095 households, out of which 28.60% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.90% were married couples living together, 7.90% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.80% were non-families. 27.00% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.97.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 24.80% under the age of 18, 7.90% from 18 to 24, 24.80% from 25 to 44, 24.10% from 45 to 64, and 18.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 98.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.40 males.

In 2017, there were 134 births, giving a general fertility rate of 66.0 births per 1000 women aged 15–44, the 25th highest rate out of all 72 Wisconsin counties.[23] Additionally, there were no reported induced abortions performed on women of Rusk County residence in 2017.[24]

Communities[edit]

City[edit]

- Ladysmith (county seat)

Villages[edit]

Towns[edit]

Unincorporated communities[edit]

Ghost towns[edit]

- Atlanta

- Big Bend

- Crane

- Egypt

- Horseman (Varner)

- Jerome

- Kalish

- Mandowish (Manedowish)

- Poplar / Beldonville

- Pre Bram

- Shaws Farm

- Teresita

- Tibbets

- Vallee View / Walrath

- West Ingram

- Wilson Center / Dogville (Starez)

Politics[edit]

Between 1928 and 2008, Rusk County backed the nationwide winner on all but two occasions (1972 and 1988). In 2012, Mitt Romney defeated Barack Obama in the county by a margin of less than 4%, after Obama had won the county by more than 8% in 2008 over John McCain. Rusk County moved significantly to the right in 2016, as Donald Trump took over 64% of the county's vote and won by a margin of nearly 34%, the best margin of victory for any candidate in the county since 1920. He further increased his margin of victory to nearly 35% in 2020 while turning in the best vote share for a Republican in the county in a century at nearly 67%.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 5,257 | 66.66% | 2,517 | 31.92% | 112 | 1.42% |

| 2016 | 4,564 | 64.39% | 2,171 | 30.63% | 353 | 4.98% |

| 2012 | 3,676 | 51.12% | 3,397 | 47.24% | 118 | 1.64% |

| 2008 | 3,253 | 44.73% | 3,855 | 53.01% | 164 | 2.26% |

| 2004 | 3,985 | 50.27% | 3,820 | 48.19% | 122 | 1.54% |

| 2000 | 3,758 | 51.02% | 3,161 | 42.91% | 447 | 6.07% |

| 1996 | 2,219 | 33.40% | 2,941 | 44.27% | 1,483 | 22.32% |

| 1992 | 2,430 | 30.50% | 3,376 | 42.37% | 2,161 | 27.12% |

| 1988 | 3,063 | 43.73% | 3,888 | 55.51% | 53 | 0.76% |

| 1984 | 4,061 | 50.90% | 3,843 | 48.16% | 75 | 0.94% |

| 1980 | 3,704 | 47.52% | 3,584 | 45.98% | 507 | 6.50% |

| 1976 | 2,724 | 39.15% | 4,050 | 58.21% | 183 | 2.63% |

| 1972 | 3,007 | 47.89% | 3,075 | 48.97% | 197 | 3.14% |

| 1968 | 2,666 | 44.74% | 2,559 | 42.94% | 734 | 12.32% |

| 1964 | 2,214 | 34.57% | 4,176 | 65.20% | 15 | 0.23% |

| 1960 | 3,094 | 45.48% | 3,692 | 54.27% | 17 | 0.25% |

| 1956 | 3,433 | 53.68% | 2,929 | 45.80% | 33 | 0.52% |

| 1952 | 4,134 | 59.36% | 2,777 | 39.88% | 53 | 0.76% |

| 1948 | 2,623 | 42.04% | 3,401 | 54.51% | 215 | 3.45% |

| 1944 | 3,092 | 48.40% | 3,238 | 50.69% | 58 | 0.91% |

| 1940 | 3,484 | 48.66% | 3,578 | 49.97% | 98 | 1.37% |

| 1936 | 2,453 | 36.18% | 3,877 | 57.18% | 450 | 6.64% |

| 1932 | 1,942 | 35.90% | 3,194 | 59.04% | 274 | 5.06% |

| 1928 | 3,524 | 63.62% | 1,925 | 34.75% | 90 | 1.62% |

| 1924 | 1,932 | 39.11% | 272 | 5.51% | 2,736 | 55.38% |

| 1920 | 2,609 | 77.60% | 441 | 13.12% | 312 | 9.28% |

| 1916 | 989 | 47.59% | 926 | 44.56% | 163 | 7.84% |

| 1912 | 575 | 33.78% | 522 | 30.67% | 605 | 35.55% |

| 1908 | 1,431 | 67.82% | 532 | 25.21% | 147 | 6.97% |

| 1904 | 1,415 | 81.51% | 247 | 14.23% | 74 | 4.26% |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "2020 Decennial Census: Rusk County, Wisconsin". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v History of Rusk County Wisconsin. Ladysmith, Wisc.: Rusk County Historical Society. 1983.

- ^ Peters, James; Wyatt, Barbara (September 1, 1978). "Flambeau Mission Church". NRHP Inventory-Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ Dahl, Ole Rasmussen (1880). Map of Chippewa, Price & Taylor Counties and the northern part of Clark County. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Milwaukee Litho & Engr Co. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Foote, Charles M.; Brown, W.S. (1888). Plat Book of Chippewa County, Wisconsin, Drawn from Actual Surveys and County Records. Minneapolis, Minn.: C.M. Foote & Co. p. 7. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Eke, Paul (May 3, 1923). "Early Days in Rusk County". Ladysmith Journal. Retrieved January 5, 2024. The WHS historical marker on the CR&M says the logging railroad started in 1874, but all other sources, including the 1983 History of Rusk County, agree on 1884.

- ^ a b Brown, R.C. (Doc) (1982). Logging Railroads of Rusk County, Wisconsin. Eau Claire.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Gates County Courthouse". Rusk County Historical Society Museum. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ Ogle, George A. (1914). Standard Atlas of Rusk County, Wisconsin: Including a Plat Book of the Villages, Cities and Townships of the County. Chicago, Ill.: George A. Ogle & Co. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ^ "Wisconsin School Districts Reorganized" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Kurtz, Bill (July 5, 2002). "Mount Scenario loses its struggle for survival". Superior Catholic Herald. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Reclaimed Flambeau Mine". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "Top Employers". Rusk County Development. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ "County Population Totals: 2010-2020". Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Annual Wisconsin Birth and Infant Mortality Report, 2017 P-01161-19 (June 2019): Detailed Tables". Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Reported Induced Abortions in Wisconsin, Office of Health Informatics, Division of Public Health, Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Section: Trend Information, 2013-2017, Table 18, pages 17-18

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Dresden, Katharine Woodrow. History of Rusk County, Wisconsin. Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1931.

External links[edit]

- Rusk County government website

- Rusk County map from the Wisconsin Department of Transportation

- Old county maps: 1873 18801888 19011901-1905191419151915-1920