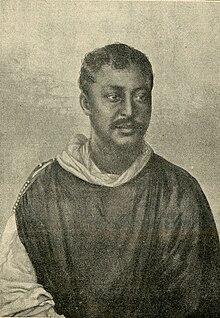

Ras Mengesha Yohannes

Ras Mengesha Yohannes | |

|---|---|

መንገሻ ዮሓንስ | |

| |

| Born | 1868 |

| Died | 1906 (aged 37–38) |

Ras Mengesha Yohannes (Tigrinya: መንገሻ ዮሓንስ; 1868 – 1906) was governor of Tigray and a son of Emperor Yohannes IV (r. 1872-89). His mother was Welette Tekle Haymanot wife of dejazmach Gugsa Mercha. Ras Araya Selassie Yohannes was his younger half brother. Prior to the Battle of Metemma, Mengesha Yohannes was considered to be a nephew of Emperor Yohannes IV. During the battle, the Emperor was mortally wounded and it was on his deathbed that Mengesha Yohannes was acknowledged as his "natural" son and designated as his heir. This created something of a succession problem.[1]

Fighting between various relatives of the slain Emperor split his camp and prevented Mengesha from making a viable bid for the Imperial throne. Instead, the throne was assumed by Negus Menelik of Shewa. Ras Mengesha refused to submit to Menelik and later even flirted with joining the new Italian colony of Eritrea. He hoped that the Italians would support his rebellion against Emperor Menelik. However, encroachments by the Italians into his native Tigray, their previous enmity to his father Yohannes, and recognition that the ultimate goal of the Italians was to conquer Ethiopia themselves, led Mengesha Yohannes to finally submit to Menelik II. On 2 June 1894, he and his three major lieutenants went to the new capital at Addis Ababa. Within the newly constructed reception hall of the Grand Palace, the Emperor awaited them. He was seated on his throne with a large crown on his head. Mengesha Yohannes and his lieutenants each carried a rock of submission on his shoulder. They approached, prostrated themselves, and asked for forgiveness. Menelik simply declared them pardoned.[2][3]

Following their allegiance with Menelik, they returned to Tigray, where Bahta Hagos initiated the rebellion against the Italians. Mengesha then led his army against the Italians at the Battle of Coatit, where his force was rebuffed. Another skirmish led by Fitawrari Gebeyehu, the vanguard commander of Menelik forces on the way to Adwa, annihilated the Italians at Amba Alagi. The war culminated in 1896, as Mengesha Yohannes and the forces of Tigray fought at the side of Menelik against the Italians at the pivotal Battle of Adwa.[4] In 1899, Mengesha Yohannes rebelled again against Menelik when he was denied the title of Negus of Zion (his descendants would be outraged decades later when Ras Mikael of Wollo was crowned with this title by Lij Iyasu). Emperor Menelik had Ras Mengesha captured and put under house arrest at the old Shewan royal palace at Ankober.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Before 1889, Mengesha Yohannes was considered the Emperor's nephew, but on 9 March 1889 the Emperor on his deathbed, in Metemma, recognized him as his son, from a side-relation with his brother Gugsa's wife. Therefore, some informants still claim that Mengesha Yohannes was strongly attached to Yohannes throughout his life. Dejazmach Mengesha Yohannes was designated by the Emperor as his heir-to-the-throne, and allegedly crowned still on the battlefield of Metemma, but Mengesha Yohannes was not able to claim the throne. In the aftermath of the disastrous battle of Metemma, the Tigrayan ruling families found themselves embroiled in a power struggle that led to a regional civil war.[5][6][7] This state of anarchy sapped the energy of Mengesha Yohannes's camp to unite the region under his authority. Quickly, instead atse Menelik II was proclaimed emperor in November 1889.

Ras Mengesha Yohannes, however, had the strong military and political backing of Yohannes's chief military general ras Alula Engada. Additionally, he had inherited a considerable number of armaments and soldiers that had long bolstered the power of Yohannes IV. However, historians cast doubts on Mengesha Yohanens's basic military prowess and leadership skills to mobilize the available resources and prevail over rivals, in contrast to his predecessor Yohannes. Mengesha Yohannes's strong political ambition once nearly pushed him to ally with the Italians, as demonstrated by the Mereb Convention of 1891.[8] By 1890, the Italians had taken control of the Mereb Mellash, and aimed at the control of entire Tigray. In the meanwhile, Mengesha Yohannes and his Tigrayan vassals had revolted against atse Menelik II. Italian attempts to instigate them were, nonetheless, short-lived. The Italians' non-committed stance, coupled with Mengesha Yohannes's hesitant attitude finally convinced him to end his rebellion, even against the opposition of his counsellors and his military supporters, such as ras Alula.[6]

Rule[edit]

In June 1894, Mengesha Yohannes ultimately dropped his claims to the imperial throne and officially submitted to atse Menelik II, ostensibly in expectation of the title of negus of Tigray. Menelik, in turn, appointed him governor, not negus of Tigray. For a while, Mengesha Yohannes demonstrated his loyalty. The conflict subsequently developing between the Italians and Menelik, gave him the opportunity to prove his indispensability to the central government.

During the first phase, in the years 1894-95, the Italians made a number of incursions into northern Ethiopia. Mengersha Yohannes was then responsible for defending the northern borders. He was beaten in the two battles of Kweatit (1894), Senafe (Eritrea) and Debre Hayle (1895): in early 1896 he even retreated from his stronghold Mekelle, but kept the Italians busy until a united Ethiopian army was gathered to face them.

Ras Mengesha Yohannes played an even more important role in the next phase of the conflict. Together with ras Alula, he was largely responsible for organizing and running the intelligence of Menelik II. He exploited his local connections, gathered intelligence and rendered a fairly outstanding command of the Tigrayan army. All these inputs had a crucial role in deciding the outcome of the battle of Adwa in 1896, which ended up as a grim loss to the Italians.[5]

Despite Mengesha Yohannes's retention of "Tigray proper", Eritrea remained in the hands of the Italians. His proposal to sustain the war to push the Italians out of Eritrea was played down by the Emperor, who focused on the control of his own realm. Menelik officially rewarded Mengesha Yohannes with 300,000 silver dollars and married him to Kafay Wele Batul of Yejju, atege Taytu's niece. The marriage was meant to cement further the bonds between the houses of Tigray, Shewa, and Yejju. It was obtained at the cost of divorcing his loving wife. Still, Mengesha Yohannes's long expectations of promotion to negus of Tigray were shattered for the second time.[8]

Mengesha Yohannes's final and desperate rebellion (in concert with ras Sebhat of Agame) in 1898 ended with his captivity and confinement at Addis Ababa, starting from 1899, and then in Ankober where he died as a prisoner in 1906.[9]

Mengesha Yohannes's controversial political career, however, left a legacy of Tigrayan identity and autonomy. Indeed, his son leul ras Seyoum Mengesha and his grandson, leul ras Mengesha Seyoum were able to gain the governorship of Tigray, each at different stages of the history of this region (sometimes also partitioned among several governors, relatives of Mengesha Yohannes), until the 1974 Revolution. Mengesha Seyoum played then a role as the leader of an anti-Derg oppositional party, the Ethiopian Democratic Union, which dates back to the mid-1970s.

Succession problems[edit]

The confusion over Ras Mengesh's parentage is due to the fact that his mother Wolete Tekle Haymanot Tomcho (Woizero Tekle) was betrothed to Dejazmatch Gugsa. On the death of Ras Arya Sellassie, son and heir of Yohannes, the title of Ras was conferred on Mengesha and the army of Ras Araya Sellassie was transferred under his command. It was only on his deathbed, at Metemma, that Yohannes declared to Etchege Tewoflos and the important dignitaries present that Mengesha was not the son of his brother Gugsa, but his. He thus acknowledged him as his son and declared him as his heir. Immediately after this announcement, close relatives of Yohannes, such as Fitawrari Meshesha, son of Maru, Yohannes's brother, and Dejach Bogale Araya, son of Ras Araya Dimtsu, maternal uncle of Yohannes, refused to accept Mengesha as the son and heir of Yohannes, claiming that they were equally entitled to succeed the deceased Emperor.

Since Gugsa had the same father and mother as Yohannes, the legitimacy of Mengesha would not have been affected if Yohannes had declared that he had chosen Mengesha, his nephew, as his heir. Mengesha, through his mother, had also additional claim to the Imperial lineage.[10] The only reason for claiming Mengesha as his own son was simply ro reveal the truth, which hitherto was kept secret due to the close association that had existed between Yoahannes's elder brother Dejazmatch Gugsa and Woizero Tekle, the mother of Mengesha.

Augusus B. Wylde, a correspondent of the British paper, The Manchester Guardian, who had been in Ethiopia as a member of the Hewett Mission of 1884 and later, soon after the Battle of Adwa of 1896, contends that Mengesha was indisputably the actual son Yohannes.[11] Bairu Tefla, on the other hand, although he is aware of the various sources, which assert that Mengesha was the natural son of Yohannes, has placed him as the son of Gugsa[12] on the ground that "Most of the old people agree that Mengesha was the son of Gugsa, the eldest brother of the sovereign."

Familial rivalry and division of Tigray[edit]

Even after the submission of Mengesha Yohannes, familial rivalry between the two lines of descent from Emperor Yohannes IV proved to be a difficult issue for Emperor Menelik II and his successors. Yohannes IV was survived by his elder "legitimate" son Ras Araya Selassie Yohannes and by his younger "natural" son Mengesha. Ras Araya's son Gugsa Araya, and Ras Mengesha's son Ras Seyoum would for a time divide Tigray between them, with Ras Gugsa Araya ruling the eastern half and Ras Seyoum the western half.[3]

Eventually Mengesha's son Ras Seyoum was made Leul of all Tigray in succession to his father after the death of his cousin Ras Gugsa Araya and after the treason of Gugsa Araya's son, Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa. In 1935, Haile Selassie Gugsa joined forces with the Italian invaders when they conquered Ethiopia and occupied the country.[4]

Ras Mengesha is regarded as the founder of one of the two senior cadet branches of the Ethiopian Imperial Solomonic Dynasty.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Battle of Gallabat (also known as the Battle of Metemma)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Marcus, A History of Ethiopia, pg.89

- ^ Marcus, A History of Ethiopia, pg.95

- ^ a b "A Glimpse of History Power, Treachery, Diplomacy and War in Ethiopia 1889-1906 RP Vol. IX No. XXVII, MMXVI".

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Caulk, Richard (2002). Between the Jaws of Hyenas. Wiesbaden. pp. 555–566.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Erlich, Haggai (1982). Ethiopia and Eritrea during the Scramble for Africa: a Political Biography of Ras Alula, 1875-1897. East Lansing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zewde, Bahru (1991). A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855-1974. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Berhane, Mekonnen (1994). The Political History of Tigray: Shewan Centralization versus Tigrayan Regionalism. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University. pp. 75f.

- ^ Berhe, Tsegay (1996). A History of Agame, 1822-1914. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University. p. 165.

- ^ Tubiana, Joseph (1967). Quatre généalogies royales éthiopiennes. Paris: Cahiers D'Etudes Africaines. pp. 491–505.

- ^ Wylde, A.B. (1901). Modern Abyssinia. London. pp. 179, 315.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Tafla, Bairu. A Chronicle of Emperor Yohannes IV.