Psychology of art

The psychology of art is the scientific study of cognitive and emotional processes precipitated by the sensory perception of aesthetic artefacts, such as viewing a painting or touching a sculpture. It is an emerging multidisciplinary field of inquiry, closely related to the psychology of aesthetics, including neuroaesthetics.[1][2]

The psychology of art encompasses experimental methods for the qualitative examination of psychological responses to art, as well as an empirical study of their neurobiological correlates through neuroimaging.[3][4][5][6]

History[edit]

1880-1950[edit]

One of the earliest to integrate psychology with art history was Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945), a Swiss art critic and historian, whose dissertation Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur (1886) attempted to show that architecture could be understood from a purely psychological (as opposed to a historical-progressivist) point of view.[7]

Another important figure in the development of art psychology was Wilhelm Worringer, who provided some of the earliest theoretical justification for expressionist art. The Psychology of Art (1925) by Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) is another classical work. Richard Müller-Freienfels was another important early theorist.[8]

The work of Theodor Lipps, a Munich-based research psychologist, played an important role in the early development of the concept of art psychology in the early decade of the twentieth century.[citation needed] His most important contribution in this respect was his attempt to theorize the question of Einfuehlung or "empathy", a term that was to become a key element in many subsequent theories of art psychology.[citation needed]

Numerous artists in the twentieth century began to be influenced by the psychological argument, including Naum Gabo, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and somewhat Josef Albers and György Kepes. The French adventurer and film theorist André Malraux was also interested in the topic and wrote the book La Psychologie de l'Art (1947-9) later revised and republished as The Voices of Silence.

1950-present[edit]

Though the disciplinary foundations of art psychology were first developed in Germany, there were soon advocates, in psychology, the arts or in philosophy, pursuing their own variants in the USSR, England (Clive Bell and Herbert Read), France (André Malraux, Jean-Paul Weber, for example), and the US.[citation needed]

In the US, the philosophical premises of art psychology were strengthened—and given political valence—in the work of John Dewey.[10] His Art as Experience was published in 1934, and was the basis for significant revisions in teaching practices whether in the kindergarten or in the university. Manuel Barkan, head of the Arts Education School of Fine and Applied Arts at Ohio State University, and one of the many pedagogues influenced by the writings of Dewey, explains, for example, in his book The Foundations of Art Education (1955), that the aesthetic education of children prepares the child for a life in a complex democracy. Dewey himself played a seminal role in setting up the program of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which became famous for its attempt to integrate art into the classroom experience.[11]

The growth of art psychology between 1950 and 1970 also coincided with the expansion of art history and museum programs. The popularity of Gestalt psychology in the 1950s added further weight to the discipline. The seminal work was Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality (1951), that was co-authored by Fritz Perls, Paul Goodman, and Ralph Hefferline. The writings of Rudolf Arnheim (born 1904) were also particularly influential during this period. His Toward a Psychology of Art (Berkeley: University of California Press) was published in 1966. Art therapy drew on many of the lessons of art psychology and tried to implement them in the context of ego repair.[12] Marketing also began to draw on the lessons of art psychology in the layout of stores as well as in the placement and design of commercial goods.[13]

Art psychology, generally speaking, was at odds with the principles of Freudian psychoanalysis with many art psychologists critiquing what they interpreted as its reductivism. Sigmund Freud believed that the creative process is an alternative to neuroses. He felt that it was likely a sort of defence mechanism against the negative effects of neuroses, a way to translate that energy into something socially acceptable, which could entertain and please others.[14] The writings of Carl Jung, however, had a favorable reception among art psychologists given his optimistic portrayal of the role of art and his belief that the contents of the personal unconscious and, more particularly, the collective unconscious, could be accessed by art and other forms of cultural expression.[15][16]

By the 1970s, the centrality of art psychology in academy began to wane. Artists became more interested in psychoanalysis[17] and feminism,[18] and architects in phenomenology and the writings of Wittgenstein, Lyotard and Derrida. As for art and architectural historians, they critiqued psychology for being anti-contextual and culturally naive. Erwin Panofsky, who had a tremendous[peacock prose] impact on the shape of art history in the US, argued that historians should focus less on what is seen and more on what was thought.[19][20] Today, psychology still plays an important role in art discourse, though mainly in the field of art appreciation.[7]

Because of the growing interest in personality theory—especially in connection with the work of Isabel Briggs Myers and Katherine Briggs (developers of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator)—contemporary theorists are investigating the relationship between personality type and art. Patricia Dinkelaker and John Fudjack have addressed the relationship between artists' personality types and works of art; approaches to art as a reflection of functional preferences associated with personality type; and the function of art in society in light of personality theory.[21]

Aesthetic Experience[edit]

Art is considered to be a subjective field, in which one composes and views artwork in unique ways that reflect one's experience, knowledge, preference, and emotions. The aesthetic experience encompasses the relationship between the viewer and the art object. In terms of the artist, there is an emotional attachment that drives the focus of the art. An artist must be completely in-tune with the art object in order to enrich its creation.[22] As the piece of art progresses during the creative process, so does the artist. Both grow and change to acquire new meaning. If the artist is too emotionally attached or lacking emotional compatibility with a work of art, then this will negatively impact the finished product.[22] According to Bosanquet (1892), the "aesthetic attitude" is important in viewing art because it allows one to consider an object with ready interest to see what it suggests. However, art does not evoke an aesthetic experience unless the viewer is willing and open to it. No matter how compelling the object is, it is up to the beholder to allow the existence of such an experience.[23]

In the eyes of Gestalt psychologist Rudolf Arnheim, the aesthetic experience of art stresses the relationship between the whole object and its individual parts. He is widely known for focusing on the experiences and interpretations of artwork, and how they provide insight into peoples' lives. He was less concerned with the cultural and social contexts of the experience of creating and viewing artwork. In his eyes, an object as a whole is considered with less scrutiny and criticism than the consideration of the specific aspects of its entity. Artwork reflects one's "lived experience" of his/her life. Arnheim believed that all psychological processes have cognitive, emotional, and motivational qualities, which are reflected in the compositions of every artist.[22]

Psychological research[edit]

Overview: bottom-up and top-down processing[edit]

Cognitive psychologists consider both "bottom-up" and "top-down" processing when considering almost any area of research, including vision.[24][25][26] Similar to how these terms are used in software design, "bottom-up" refers to how information in the stimulus is processed by the visual system into colors, shapes, patterns, etc.[24][25] "Top-down" refers to conceptual knowledge and past experience of the particular individual.[24][25] Bottom-up factors identified in how art is appreciated include abstract vs figurative painting, form, complexity, symmetry and compositional balance, laterality and movement.[24] Top-down influences identified as being related to art appreciation include prototypicality, novelty, additional information like titles, and expertise.[24]

Abstract versus figurative art[edit]

Abstract paintings are unique in the explicit abandonment of representational intentions.[27] Figurative or representational art is described as unambiguous or requiring mild interpretation.[27]

The importance of meaning[edit]

The popular distaste for abstract art is a direct consequence of semantic ambiguity.[27] Researchers have examined the role of terror management theory (TMT) concerning meaning and the aesthetic experience of abstract versus figurative art. This theory suggests that humans, like all life forms are biologically oriented toward continued survival but are uniquely aware that their lives will inevitably end. TMT reveals that modern art is often disliked because it lacks appreciable meaning, and is thus incompatible with the underlying terror management motive to maintain a meaningful conception of reality.[27] Mortality salience, or the knowledge of approaching death, was manipulated in a study aimed at examining how aesthetic preferences for seemingly meaningful and meaningless art are influenced by intimations of mortality. The mortality salience condition consisted of two opened ended questions about emotions and physical details concerning the participant's own death.[27] Participants were then instructed to view two abstract paintings and rate how attractive they find them. A test comparing the mortality salience condition and the control found that participants in the mortality salience condition found the art less attractive.[27]

The meaning maintenance model of sociology states that when a committed meaning framework is threatened, people experience an arousal state that prompts them to affirm any other meaning framework to which they are committed.[28] Researchers sought to illustrate this phenomenon by demonstrating a heightened personal need for structure following the experience of abstract artwork.[28] Participants were randomly assigned to a between-subjects viewing of artwork (abstract vs. representational vs. absurd artwork), followed by allocation of the Personal Need for Structure scale. Personal Need for Structure scale is used to detect temporary increases in people's need for meaning.[28] Theoretically, one should experience more need for structure when viewing abstract art than figurative art since unrelated meaning threats (abstract art) evoke a temporarily heightened general need for meaning.[28] However, results showed that overall scores for representational art, and abstract art did not differ significantly from one another. Participants reported higher scores on the Personal Need for Structure scale in absurd rather than abstract art. Yet, the question remains as to whether the same kinds of results would be obtained with an expanded sample of abstract expressionist or absurd images.[28]

Complexity[edit]

Studies have shown that when looking at abstract art, people prefer complexity in the work to a certain extent. When measuring "interestingness" and "pleasingness," viewers rated works higher for abstract works that were more complex. With added exposure to the abstract work, liking ratings continued to rise with both subjective complexity (viewer rated) and judged complexity (artist rated). This was only true up to a certain point. When the works became too complex, people began to like the works less.[29]

Neural evidence[edit]

Neuroanatomical evidence from studies using fMRI scans of aesthetic preference show that representational paintings are preferred over abstract paintings.[30] This is displayed through significant activation of brain regions related to preference ratings.[30] To test this, researchers had participants view paintings that varied according to type (representational vs. abstract) and format (original vs. altered vs. filtered). Behavioral results demonstrated a significantly higher preference for representational paintings.[30] A positive correlation existed between preference ratings and response latency. FMRI results revealed that activity in the right caudate nucleus extending to putamen decreased in response to decreasing preference for paintings, while activity in the left cingulate sulcus, bilateral occipital gyri, bilateral fusiform gyri, right fusiform gyrus, and bilateral cerebellum increased in response to increasing preference for paintings.[30] The observed differences were a reflection of relatively increased activation associated with higher preference for representational paintings.[30]

Brain wave studies have also been conducted to look at how artists and non-artists react in different ways to abstract and representational art. EEG brain scans showed that while viewing abstract art, non-artists showed less arousal than artists. However, while viewing figurative art, both artists and non-artists had comparable arousal and ability to pay attention and evaluate the art stimuli. This suggests abstract art requires more expertise to appreciate it than does figurative art.[31]

Personality type[edit]

Individual personality traits are also related to aesthetic experience and art preference. Individuals chronically disposed to clear, simple, and unambiguous knowledge express a particularly negative aesthetic experience towards abstract art, due to the void of meaningful content.[27] Studies have provided evidence that a person's choice of art can be a useful measure of personality.[32] Individual personality traits are related to aesthetic experience and art preference. Testing personality after viewing abstract and representational art was performed on the NEO Five-Factor Inventory which measures the "big five" factors of personality.[32] When referencing the "Big Five" dimensions of personality, Thrill and Adventure Seeking were positively correlated with a liking of representational art, while Disinhibition was associated with positive ratings of abstract art. Neuroticism was positively correlated with positive ratings of abstract art, while Conscientiousness was linked to liking of representational art. Openness to Experience was linked to positive ratings of abstract and representational art.[32]

Automatic evaluation[edit]

Studies looking at implicit, automatic evaluation of art works have investigated how people react to abstract and figurative art works in the split-second before they had time to think about it. In implicit evaluation, people reacted more positively to the figurative art, where they could at least make out the shapes. In terms of explicit evaluation, when people had to think about the art, there was no real difference in judgement between abstract and representational art.[33]

Laterality and movement[edit]

Handedness and reading direction[edit]

Laterality and movement in visual art includes aspects such as interest, weight, and balance. Many studies have been conducted on the impact of handedness and reading direction on how one perceives a piece of art. Research has been conducted to determine if hemispheric specialization or reading habits affect the direction in which participants "read" a painting. Results indicate that both factors contribute to the process. Furthermore, hemispheric specialization leads individuals to read from left to right, giving those readers an advantage.[34] Building off of these findings, other researchers studied the idea that individuals who are accustomed to reading in a certain direction (right to left, versus left to right) would then display a bias in their own representational drawings reflecting the direction of their reading habits. Results indicated that this prediction held true, in that participants' drawings reflected their reading bias.[35]

Researchers also looked to see if one's reading direction, left to right or right to left affects one's preference for either a left to right directionality or a right to left directionality in pictures. Participants were shown images as well as its mirror image, and were asked to indicate which they found more aesthetically pleasing. Overall, results indicate that one's reading directionality impacts one's preference for pictures either with left to right directionality or right to left directionality.[36]

In another study, researchers examined if the right-side bias in aesthetic preference is affected by handedness or reading/writing habits. The researchers looked at Russian readers, Arabic readers, and Hebrew readers that were right handed and non-right-handed. Participants viewed pictures taken from art books that were profiles or human faces and bodies in two blocks. Images were shown to participants as inward or outward facing pairs and then in the opposite orientation. After viewing each pair, participants were asked which image of the pair was more aesthetically pleasing. When looking at the results for handedness, right-handed participants had "left preferences" and non-right-handed participants had "right preferences". These results indicated that "aesthetic preference for facial and bodily profiles is associated primarily with the directionality of acquired reading/writing habits."[37] Reading direction seems to impact how people of all ages view artwork. Using kindergarten to college aged participants, researchers tested viewers' aesthetic preference when comparing an original piece of art with its mirror image. The original paintings followed the convention that viewers "read" paintings from left to right; therefore, the patterns of light directed the audience to view the painting in the same manner. Findings indicated that participants preferred the original paintings, most likely due to the western style of viewing paintings from left to right.[38]

Lighting direction[edit]

The direction of the lighting placed on a painting also seems to have an effect on aesthetic preference. The left-light bias is the tendency for viewers to prefer artwork that is lit with lighting coming from the left hand side of the painting. Researchers predicted that participants would prefer artwork that was lit from the left side and when given the option, they would choose to place lighting on the upper left side of a piece of artwork. Participants found paintings with lighting on the left to be more aesthetically pleasing than when it was lighter on the right side and when given the opportunity to create light on an already existing painting.[39]

Left and right cheek bias[edit]

The left cheek bias occurs when viewers prefer portraits with the subject displaying their left cheek, while those that hold a right cheek bias prefer portraits displaying the right cheek. Studies have found mixed results concerning the left cheek bias and the right cheek bias. Male and female participants were shown male and female portraits, each displaying an equal number of left or right cheek positions. Participants were shown each portrait in its original orientation and in its reversed orientation and asked which portrait they preferred more. Results indicated that the majority of participants chose portraits displaying the subject's right cheek over the left.[40] Another study explored which posing orientations conveyed certain messages. Scientists in the 18th century[citation needed] more commonly displayed a right cheek bias, and were rated as "more scientific". According to the researchers, showing one's right cheek hides emotion, while the left cheek expresses it. The shift from right to left cheek bias post 18th century may represent more personal or open facial characteristics.[41] Additionally, a historical preference to artistically display or render half-left profiles in single subject portraits across various media, found in almost 5,000 works of art, suggests that differential left/right hemisphere activation proclivities in artists of a particular sex and handedness might influence aesthetic composition [42][43]

Complexity[edit]

Complexity can literally be defined as being "made up of a large number of parts that have many interactions."[44] This definition has been applied to many subjects, such as art, music, dance, and literature. In aesthetics research, complexity has been divided into three dimensions that account for the interaction between the amount of elements, differences in elements, and patterns in their arrangement. Furthermore, this characteristic in aesthetics consists of a wide spectrum, ranging from low complexity to high complexity. Key studies have found through Galvanic skin response that more complex artworks produce greater physiological arousal and higher hedonic ratings,[45] which is consistent with other findings that claim that aesthetic liking increases with complexity. Most important, several studies have found that there exists a U-shape relationship between aesthetic preference and complexity.[46]

Measuring complexity[edit]

In general, complexity is a something that has many parts in an intricate progression. Some researchers break complexity down into two different subparts: objective complexity and perceived complexity. Objective complexity is any part of art that could be manipulated. For visual art that may be the size of the shapes, the number of patterns, or the number of colors used. For acoustic art that could include duration, loudness, number of different harmonies, number of changes in rhythmic activity, and rate of rhythmic activity.[47] Another form of complexity is perceived complexity, or subjective complexity. In this form each individual person rates an object on the complexity they perceive. Therefore, subjective complexity might depict our view of complexity more accurately, however, the measure may change from person to person.

One form of using computer technology to rate complexity, is by using computer intelligence when rating an image.[48] In this format, the amount of computer intelligence used is assessed when creating a digital image. Computer intelligence is assessed by recording the mathematic formulas used in creating the images. Human involvement, adding or taking away aspects of the image, could also add or take away from the complexity of the image.[48]

One way to measure complexity is to manipulate original artwork to contain various levels of density. This process is done by subtracting and adding pixels to change the density of black and white paintings. This technique allowed researchers to use authentic artwork, instead of creating artificial versions of artwork, to control stimuli.[49]

Still others find it best to measure complexity based on the number of parts an artwork has.[50] More aspects to the art, such as more colors, details, shapes, objects, sounds, melodies, and the like, create a more complex artwork. However, there is limited research done on the comparison between part based complexity and human perception of complexity, making it unclear if people perceive images with more parts as being more complex.[citation needed]

Inverse U-Shape hypothesis[edit]

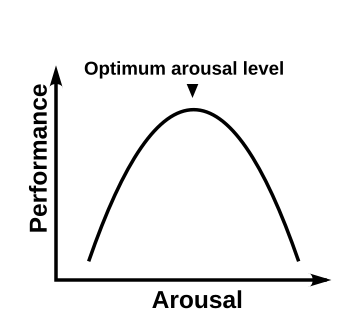

The Inverted U-Shape Hypothesis suggests that aesthetic responses in relation to complexity will exhibit an inverted-shape distribution. In other words, the lowest ratings in aesthetic responses correlate with high and low levels of complexity, which displays an "avoidance of extremes". Furthermore, the highest level of aesthetic response occurs in the middle level of complexity.[46] Previous studies have confirmed the U-Shape hypothesis (see Inverted U-graph image). For instance, in a study of undergraduates' ratings of liking and complexity of contemporary pop music reported an inverted U-shape relationship between liking and complexity.[51]

Previous research, suggest that this trend of complexity could also be associated with ability to understand, in which observers prefer artwork that is not too easy or too difficult to comprehend.[52] Other research both confirms and disconfirms predictions that suggest that individual characteristics such as artistic expertise and training can produce a shift in the inverted U-shape distribution.[51]

Aspects of art[edit]

- Visual art

A general trend shows that the relationship between image complexity and pleasantness ratings form an inverted-U shape graph (see Expertise section for exceptions). This means that people increasingly like art as it goes from very simple to more complex, until a peak, when pleasantness ratings being to fall again.

A recent study had also found that we tend to rate natural environment and landscape images as more complex, hence liking them more than abstract images that we rate as less complex.[53]

- Music

Music shows similar trends in complexity vs. preference ratings as does visual art. When comparing popular music, for the time period, and perceived complexity ratings the known inverted-U shape relationship appears, showing that generally we like moderately complex music the most.[51] As the music selection gets more or less complex, our preference for that music dips. People who have more experience and training in popular music, however, prefer slightly more complex music.[51] The inverted-U graph shifts to the right for people a stronger musical background. A similar pattern can be seen for jazz and bluegrass music.[47] Those with limited musical training in jazz and bluegrass demonstrate the typical inverted-U when looking at complexity and preference, however, experts in those fields do not demonstrate the same pattern. Unlike the popular music experts, jazz and bluegrass experts did not show a distinct relationship between complexity and pleasantness. Experts in those two genres of music seem to just like what they like, without having a formula to describe their behavior. Since different styles of music have different effects on preference for experts, further studies would need to be done to draw conclusions for complexity and preference ratings for other styles.

- Dance

Psychological studies have shown that the hedonic likings of dance performances can be influenced by complexity. One experiment used twelve dance choreographies that consist of three levels of complexity performed at four different tempos. Complexity in the dance sequences were created varying the sequence of six movement patterns (i.e. circle clockwise, circle counterclockwise, and approach stage). Overall, this studied showed that observers prefer choreographies with complex dance sequences and faster tempos.[54]

Personal differences[edit]

It has been found that personality differences and demographic differences may lead different art preferences as well. One study tested peoples preferences on various art pieces, taking into account their personal preferences as well. The study found that gender differences exist in art preference. Women generally prefer happy, colorful, and simple paintings whereas men generally prefer geometric, sad, and complex paintings. An age difference in complexity preferences exists as well, where preference for complex paintings increases as age increases.[50]

Certain personality traits can also predict the relationship between art complexity and preference.[50] In one study it was found that people who scored high on conscientiousness liked complex painting less than people who scored low on conscientiousness. This falls in line with the idea that conscientious people dislike uncertainty and enjoy control, thereby disliking artwork that might threaten such feelings. On the other hand, people who scored highly on openness to experience liked complex artworks more than those who didn't score highly on openness to experience. Individual differences are better predictors for preference of complex art than simple art, where no clear personality traits predict preference for simple art. Although educational level did not have a direct relationship with complexity, higher educational levels led to more museum visits, which in turn led to more appreciation of complex art.[50] This shows that more exposure to complex art leads to greater preference, where indeed familiarity causes greater liking.

Symmetry[edit]

Symmetry is a common feature in numerous art forms. For instance, art containing geometric forms, as seen in much of Islamic art, has an inherent symmetry to the work. The use of symmetry in human artwork can be traced back as far as 500,000 years.[55] The extensive use of symmetry in artwork may be explained by the common association found between symmetry and perceived beauty.[56] Symmetry and beauty have a strong biological link that influences aesthetic preferences. It has been shown that ratings of facial attractiveness are directly related to the degree of symmetry present within a face.[56] Humans also tend to prefer art that contains symmetry, viewing it as more aesthetically pleasing.[24][57]

Humans innately tend to see and have a visual preference for symmetry, an identified quality yielding a positive aesthetic experience that uses an automatic bottom-up factor.[58] This bottom-up factor is speculated to rely on learning experience and visual processing in the brain, suggesting a biological basis.[58] Many studies have ventured to explain this innate preference for symmetry with methods including the Implicit Association Test (IAT).[59] Research suggests that we may prefer symmetry because it is easy to process; hence we have a higher perceptual fluency when works are symmetrical.[60] Fluency research draws on evidence from humans and animals that point to the importance of symmetry regardless of biological necessity. This research highlights the efficiency with which computers recognize and process symmetrical objects relative to non-symmetrical models.[60] There have been investigations regarding the objective features that stimuli contain that may affect the fluency and therefore the preferences.[60] Factors such as amount of information given, the extent of symmetry, and figure-ground contrast are only a few listed in the literature.[60] This preference for symmetry has led to question on how fluency affects our implicit preferences by using the Implicit Association Test. Findings suggest that perceptual fluency is a factor that elicits implicit responses, as shown with the Implicit Association Test results.[59] Research has branched from studying aesthetic pleasure and symmetry on an explicit but also implicit level. In fact, research tries to integrate priming (psychology), cultural influences and the different types of stimuli that may elicit an aesthetic preference.

Further research investigating perceptual fluency has found a gender bias towards neutral stimuli.[61] Studies pertaining to generalizing symmetry preference to real-world versus abstract objects allow us to further examine the possible influence meaning may have on preference for a given stimuli.[61] In order to determine whether meaning mattered for a given stimuli, participants were asked to view pairs of objects and make a forced-choice decision, evaluating their preference.[61] The findings suggest that an overall preference for symmetric features of visual objects existed. Furthermore, a main effect for gender preference existed in the males that consistently indicated a preference for symmetry in both abstract and real objects.[61] This finding did not transcend in the female participants which challenged the perceptual fluency explanation as it, in theory, should not be gendered.[61] Further studies need to be conducted to investigate the factors that influence female preferences for visual stimuli as well as for why males showed a preference for symmetry in both abstract and real world objects.[61]

The good genes hypothesis has also been proposed as an explanation for symmetry preference. It argues that symmetry is a biological indicator of stable development, mate quality and fitness and therefore explains why we choose symmetrical traits in our mates.[62] The good genes hypothesis does not, however, explain why this phenomenon is observed in our preferences for decoration art.[62] Another proposed hypothesis is the extended phenotype hypothesis that argues that decoration art is not mate-irrelevant but rather a reflection of the fitness of the artist, as symmetrical forms are difficult to produce.[62] These hypothesis and findings provide evidence for evolutionary biases on preference for symmetry and as reinforcement for cultural biases.[62] Research suggests that symmetrical preference due to its evolutionary basis, biological basis and cultural reinforcement, might be replicable cross-culturally.[62]

Types of Visual Symmetry[edit]

A pattern is considered symmetrical when it retains its appearance after the performance of an operation. There are three main operations that can be used to classify symmetry: reflection, rotation, and translation.[63] Reflectional symmetry is what is most commonly thought of and stands out as the most obvious form of symmetry.[59] A pattern is considered to have reflectional symmetry when one side of an axis is a mirror-image of the other side.[63] Rotational symmetry is present when a pattern remains the same after a rotation of any degree.[64] Translational symmetry is the repetition of a pattern such that the only change made when it is copied is to its location. Reflectional symmetry is the most salient form in human perception which may explain why participants generally exhibit a preference for reflectional symmetry over both translational and rotational symmetry in aesthetic evaluation studies.[59][65]

Generally, studies examining the effect of symmetry on aesthetic preference use stimuli with reflectional symmetry unless otherwise specified. Typically, if a study is investigating different types of symmetry (e.g. rotational), it is because they are including symmetry type as an independent variable.[59][63] Exploration of the effect of symmetry type is more common for studies on the aesthetic preferences of geometric shapes or dot patterns.[65] In contrast, studies using more visually complex stimuli, such as faces or art, tend to use stimuli with solely reflectional symmetry.[66][67] Therefore, in most studies on aesthetic preferences, the use of the term “symmetry” without any reference to the specific type connotes the use of stimuli with reflectional symmetry.

Domain-Specific Symmetry Preference[edit]

The influence of symmetry on aesthetic preferences has been examined across a wide variety of stimuli including faces, shapes, patterns, objects, and paintings.[42] Aesthetic preferences for faces and shapes has been consistently associated with a higher degree of symmetry.[63][66] However, symmetry does not predict aesthetic preferences as reliably for other types of stimuli, suggesting that preference for symmetry may be domain-specific.[66] Symmetrical stimuli are often generated by transforming an originally asymmetrical image such that one half is a mirror image of the other.[66] This artificial generation of symmetry can actually have a negative effect on perceived aesthetic value.[68] In a study examining how symmetry preference differs across the domains of faces, abstract shapes, flowers, and landscapes, participants rated 6 sets of 10 differentially symmetrical image pairs in terms of their beauty and symmetry salience.[68] Symmetry salience was included as a variable in order to examine whether noticing more symmetry contributed to higher beauty ratings. Each image pair consisted of an original, slightly asymmetrical version of the stimuli and a perfectly symmetrical version. Participants first rated the beauty of every image on a scale of 1 to 10 with the images presented in a random order. They were then presented with the images again and gave a rating of how salient or clear the symmetry was on a scale of 1 to 10. While the participants exhibited a preference for the perfectly symmetrical versions of faces and shapes, they conversely preferred the less symmetrical version of landscapes and had no significant preference for flowers. Further, when they examined the relationship between perceived symmetry salience and beauty, they found that noticing greater symmetry had a positive effect on beauty ratings for abstract shapes, but a negative effect on beauty ratings for landscapes. Therefore, symmetry can contribute to perceived beauty both positively and negatively depending on the domain.

Research suggests that symmetry may not be more aesthetically pleasing when it comes to abstract artwork such as paintings.[66][67] Two different studies have indicated that symmetry is actually not viewed as more aesthetically pleasing when participants are rating abstract paintings.[66][67] Both studies used Likert rating scales to measure participants preference, with the first asking them to rate paintings on a scale of 1 to 7 in terms of “pleasantness” while the second asked for 1 to 7 ratings of how much they “like” the painting. Both studies generated the symmetrical versions of originally asymmetrical abstract paintings by mirror-imaging one half on the other. While the first study simply found that perfectly symmetrical paintings were not preferred more or less than their asymmetrical counterparts, the second found that they were actually disfavored. Therefore, aesthetic preferences for symmetry may not apply to abstract artwork, and symmetry may actually detract from its perceived aesthetic value. This could potentially be explained by the lack of complexity associated with perfectly symmetrical paintings.[24] Aesthetic preferences for artwork often involve a balance of complexity and symmetry that may not be satisfied by perfectly symmetrical abstract paintings.[24]

The Influence of Art Expertise on Symmetry Preference[edit]

Recent studies suggest that aesthetic preferences for symmetry may be influenced by art expertise.[69][70][71][72][73] However, this seems to depend on whether the evaluation task is implicit or explicit. One study examining both implicit and explicit aesthetic preferences of symmetry in abstract patterns found the difference between art experts and non-experts only arose in the explicit rating task.[70] For the implicit evaluation, participants performed an IAT using 10 positive and 10 negative words presented with 20 abstract patterns, half symmetrical and half asymmetrical. Both those with and without art expertise preferred symmetrical abstract patterns. However, differences between these two groups arose when using an explicit evaluation, in which participants gave ratings on a scale of 1 to 7 after the presentation of each abstract pattern. While preference for symmetrical over asymmetrical stimuli was stable across the two groups, participants with greater art expertise rated asymmetrical stimuli higher in aesthetic value. However, another study, using roughly the same set of abstract patterns as their stimuli, found that participants with art expertise actually rated asymmetrical stimuli higher in aesthetic value than symmetrical stimuli whereas non-experts had the opposite preference.[69] Given these mixed results, art experts’ preference for asymmetrical over symmetrical stimuli may not be universal, but there is evidence that they generally find more aesthetic value in asymmetrical stimuli than non-experts.

A proposed explanation for this phenomenon is that art experts may process complex stimuli more easily than non-experts due to their training.[24] They may have more experience both viewing and constructing asymmetrical patterns, facilitating their ability to process them quickly.[74] Therefore, according to the theory of perceptual fluency, their experience would enable more positive reactions to asymmetrical stimuli.[70] However, given that both art experts and non-experts preferred symmetrical patterns over asymmetrical ones in the IAT, some propose that art experts alter their initial impression when consciously reflecting on their preference.[70] Where the IAT measures automatic preference, explicit rating scales reflect the cognitive construction of one's preference and can therefore be influenced by outside motivations or biases. It has been proposed that art experts may wish to differentiate themselves from the masses as evidence of their artistic competence.[24] They may also have a greater appreciation for asymmetrical stimuli given its ubiquity in art history.[74] Therefore, it may not be that art experts inherently prefer visual asymmetry, but that they see its value more than non-experts given their extensive experience with asymmetrical stimuli.

Compositional balance[edit]

Compositional balance refers to the placement of various elements in a work of art in relation to each other, through their organization and positioning, and based upon their relative weights.[75] The elements may include the size, shape, color, and arrangement of objects or shapes. When balanced, a composition appears stable and visually right.[24] Just as symmetry relates to aesthetic preference and reflects an intuitive sense for how things 'should' appear, the overall balance of a given composition contributes to judgments of the work.

The positioning of even a single object, such as a bowl or a light fixture, in a composition contributes to preferences for that composition. When participants viewed a variety of objects, whose vertical positions on a horizontal plane were manipulated, participants preferred objects that were lower or higher in the plane of vision, corresponding to the normal placement of the image (e.g., a light bulb should be higher and a bowl lower). The center bias manifests can explain the preference for the most important or functional part of an object to occupy the center of the frame, suggesting a bias for a "rightness" of object viewing.[76]

We are also sensitive to balance in both abstract and representational works of art. When viewing variations on original artwork, such as the manipulation of the red, blue, and yellow areas of color in several Piet Mondrian paintings, design-trained and untrained participants successfully identified the balance centers of each variation. Both groups were sensitive to the distribution of color, weight, and area occupied. Expertise (see Art and Expertise) does not seem to have a large effect on perceiving balance, though only the trained participants detected the variation between the original work and manipulated versions.[77]

Both experts and novices tend to judge original abstract works as more optimally balanced than experimental variations, without necessarily identifying the original.[78] There appears to be an intuitive sense for experts and non-experts alike that a given representational painting is the original. Participants tend to deem original artwork as original versus the manipulated works that had been both subtly and obviously altered with respect to the balance of the painting.[79] This suggests some innate knowledge, perhaps not influenced by artistic expertise, of the rightness of a painting in its balance. Both masters and novices are equally susceptible to shifts in balance affecting preference for paintings, which may suggest that both artists viewers have an intuitive sense of balance in art.[80]

Art and expertise[edit]

Psychologists have found that a person's level of expertise in art influences how they perceive, analyze, and interact with art.[81] To test psychologically, scales have been designed to test experience rather than just years of expertise by testing recognition and knowledge of artists in a number of fields, fluid intelligence, and personality with the Big Five factor inventory.[81] These found that people with high art expertise were not significantly smarter, nor had a college major in the arts.[81] Instead, openness to experience, one of the Big Five factors, predicted someone's expertise in art.[81]

Preferences[edit]

In one study, experienced art majors and naive students were shown pairs of popular art paintings from magazines and high-art paintings, from museums.[82] Researchers found a significant interaction between expertise and art preference. Naive participants preferred popular art over high-art, while expert participants preferred high-art over popular art.[82] They also found that naive participants rated popular art as more pleasant and warm and the high-art paintings as more unpleasant and cold, while experts showed the opposite pattern.[82] Experts look to art for a challenging experience, while naive participants view art more for pleasure.[82] Systematic preferences for viewing portraiture (left or right 3/4 profiles) have been found across media, artists, styles, gender/sex, and historical epoch.[83] Both experiential tendencies and innate predispositions have been proposed to account for pose preferences.[43] Further studies controlling variables such as sex and handedness,[84] as well as ongoing hemispheric activation, have shown that these preferences can be studied across several construct dimensions.[85]

Eye movements[edit]

To investigate if experts and non-experts experience art differently even in their eye movements, researchers used an eye tracking device to see if there are any differences in the way they look at works of art.[86] After viewing each work, participants rated their liking and emotional reactions to the works.[86] Some works were presented with auditory information about that work, half of which were neutral facts and the other half were emotional statements about the work.[86] They found that non-experts rated the least abstract works more preferably, while abstraction level did not matter to the experts.[86] Across both groups, the eye paths showed more fixations within more abstract work, but each fixation was shorter in time than those within less abstract work .[86] Expertise influences how participants thought about works, but did not influence at all how they physically viewed them.[86]

In another study using eye-movement patterns to investigate how experts view art, participants were shown realistic and abstract works of art under two conditions: one asking them to free scan the works, and the other asking them to memorize them.[87] Participants' eye movements were tracked as they either looked at the images or tried to memorize them, and their recall for the memorized images was recorded.[87] The researchers found no differences in the fixation frequency or time between picture types for experts and nonexperts.[87] However, across sessions, the non-experts had more short fixations while free scanning the works, and fewer long fixations while trying to memorize; experts followed the opposite pattern.[87] There was no significant difference in the recall of the images across groups, except experts recalled abstract images better that non-experts, and more pictorial details.[87] These results show that people with arts expertise view repeated images less than non-experts, and can recall more details about images they have previously seen.[87]

Levels of abstraction[edit]

Aesthetic reactions to art can be measured on a number of different criteria, like arousal, liking, emotional content, and understanding. The art can be rated on its levels of abstraction or place in time. An experiment examining how these factors combine to create aesthetic appreciation included experts and nonexperts rating their emotional valence, arousal, liking, and comprehension of abstract, modern, and classical art works.[88] Experts demonstrated a higher degree of appreciation with higher ratings on all scales, except for arousal with classical works.[88] Classical artworks yielded the highest comprehension ratings, with abstract art receiving the lowest values.[88] However, emotional valence was highest for classical and modern art, while arousal was highest for abstract works.[88] Although experts rated the works higher overall, each factor influenced the nonexperts' ratings more, creating greater flexibility in their ratings than those of the experts.[88]

Another experiment examined the effect of color and degree of realism on participants' perception of art with differing levels of expertise. Groups of experts, relative experts, and non-experts viewed stimuli consisting of generated versions of figurative paintings varying in color and abstraction.[89] Participants rated the stimuli on their overall preference, abstractness, color properties, balance, and complexity.[89] Figurative pictures were preferred over abstract pictures with decreasing expertise and colored pictures were preferred over black-and-white pictures.[89] However, experts were more likely to prefer black-and-white pictures over colored ones than non-experts and relative experts.[89] This suggests that experts may view art with cognitive models, while non-experts view art looking for familiarity and pleasure.[89]

Other factors[edit]

An experiment studying the effect of expertise on the perception and interpretation of art had art history majors and psychology students view ten contemporary art paintings of diverse styles. Then, they grouped them into whatever labels they thought to be appropriate.[90] The data were coded to classify the categorizations and compared between experts and non-experts.[90] Experts broke down their classifications into more groups than the non-experts and categorized by style, while the non-experts depended on personal experiences and feelings.[90]

This style-related processing, which leads to a mastery of the artwork, is important in viewing modern abstract art and is affected by expertise.[91] Participants viewed and rated their liking on three sets of paintings, half of which included information about the style of the painting, such as artistic technique, stylistic features, and the materials used.[91] The next day, participants viewed new paintings, saw a blank screen, and estimated how long they had viewed the paintings.[91] Participants also completed questionnaires indicating interest in art, a questionnaire indicating expertise in art, and the "Positive and Negative Affect Schedule" mood questionnaire.[91] The effects of style-related information depended on art expertise, where non-experts liked the paintings more after receiving information about the paintings and the experts liked the paintings less after receiving style-related information.[91] Explicit style information provoked mood changes in liking, where the high Positive Affect group liked the paintings more with information and the low Positive Affect group liked the paintings less with information.[91] Art expertise did not, however, affect the estimations of presentation time.

Title information[edit]

Titles do not simply function as a means of identification, but also as guides to the pleasurable process of interpreting and understanding works of art.[92] Changing title information about a painting does not seem to affect eye movement when looking at it or how subjects interpret its spatial organization. However, titles influence a painting's perceived meaning. In one study, participants were instructed to describe paintings while using flashlight pointers to indicate where they were looking. The participants repeated this task for the same set of paintings in two sessions. During the second session, some of the paintings were presented with new titles to evaluate the consistency in their descriptions. As expected, subjects did not change where their eye-gaze focused, but they did change their descriptions by making them more consistent with a given title.[93]

Even though descriptions might fluctuate, aesthetically appreciating both abstract and representative art remains stable, regardless of different title information.[94] This suggests that word/image relations can promote different modes of understanding art, but do not account for how much we like a particular piece.[93]

A famous example of title confusion that altered a work's title/image relationship, and thus its ostensive meaning, is a painting titled La trahison des images (The treachery of images), by René Magritte, that is often referred to as "This is not a pipe". It contains an image of a pipe as well as the legend "This is not a pipe," even though that was not meant to be its title. In this case, two different understandings of the artists' intentions and the content depend on which title is chosen to go with it.[95]

Overall, random titles, other than the original, decrease understanding ratings, but do not necessarily alter the significance of aesthetic experience.[96] Elaborative, as opposed to descriptive, titles are particularly important in helping viewers assign meaning to abstract art. Descriptive titles increase understanding of abstract art only when viewers are presented with an image for a very short period of time (less than 10 seconds). Because art can have a variety of multi-leveled meanings, titles and other additional information can add to its meaningfulness and consequently, its hedonic value.[92]

Applications[edit]

Discoveries from the psychology of art can be applied to various other fields of study.[97][98] The creative process of art yields a great deal of insight about the mind. One can obtain information about work ethics, motivation, and inspiration from an artist's work process. These general aspects can transfer to other areas of one's life. Work ethic in art especially, can have a significant impact on one's overall productivity elsewhere. There is a potential in any kind of work that encourages the aesthetic frame of mind. Moreover, art defies any definite boundaries. The same applies to any such work that is aesthetically experienced.[23]

The application of psychology of art in education may improve visual literacy.[citation needed]

Criticisms[edit]

The psychology of art can be a criticized field for numerous reasons. Art is not considered a science, so research can be scrutinized for its accuracy and relativity. There is also a great deal of criticism about art research as psychology because it can be considered subjective rather than objective. It embodies the artist's emotions in an observable manner, and the audience interprets the artwork in multiple ways. The aims of an artist differ dramatically from the aims of a scientist. The scientist means to propose one outcome to a problem, whereas an artist means to give multiple interpretations of an object. The inspirations of an artist are fueled through his/her experiences, perceptions, and perspectives of the world art movements such as Expressionism are known for the artist's release of emotions, tension, pressure, and inner spiritual forces that are transcribed to external conditions. Art comes from within oneself, and it is expressed in the external world for the entertainment of others. Everyone can appreciate a piece of artwork because it speaks to each individual in unique ways—therein lies the criticism of subjectivity.[99]

In addition, the aesthetic experience of art is heavily criticized because it cannot be scientifically determined. It is completely subjective, and it relies on an individual's bias. It cannot be fundamentally measured in tangible forms. In contrast, aesthetic experiences can be deemed "self-motivating" and "self-closing".[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Tinio, P. P., & Smith, J. K. (Eds.),The Cambridge handbook of the psychology of aesthetics and the arts. Cambridge University Press, 2014. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139207058. ISBN 9781139207058.

- ^ Mather, G., The psychology of visual art: eye, brain and art. Cambridge University Press, 2013). doi:10.1017/CBO9781139030410. ISBN 9781107005983.

- ^ Mather, G., The Psychology of Art. Routledge, 2020. doi:10.4324/9780429275920. ISBN 9780367609931.

- ^ Funch, B. S., The psychology of art appreciation. Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997. ISBN 9788772894027.

- ^ Brown, S., Gao, X., Tisdelle, L., Eickhoff, S. B., & Liotti, M., Naturalizing aesthetics: brain areas for aesthetic appraisal across sensory modalities. Neuroimage, Vol. 58, Issue 1, 2011, pp. 250-258. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.012.

- ^ Cela-Conde, C. J., Agnati, L., Huston, J. P., Mora, F., & Nadal, M. (2011). The neural foundations of aesthetic appreciation. Progress in Neurobiology, Vol. 94, Issue 1, 2011, pp. 39-48. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.003.

- ^ a b Mark Jarzombek. The Psychologizing of Modernity (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- ^ Müller-Freienfels, R (1923). Psychologie der Kunst. Leipzig, Germany: Teubner.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. pp. 103, 148. ISBN 978-0-8028-3856-8.

- ^ Alan Ryan, John Dewey and the High Time of American Liberalism. W.W. Norton 1995.

- ^ Wattenmaker, Richard J.; Distel, Anne, et al. (1993). Great French Paintings from the Barnes Foundation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 6, 13–14. ISBN 0-679-40963-7.

- ^ see for example: Arthur Robbins and Linda Beth Sibley, Creative Art Therapy. (Brunner/Mazel, 1976).

- ^ See for example, Creating images and the psychology of marketing communication, Edited by Lynn R. Kahle & Chung-Hyun Kim (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2006).

- ^ Rogers, Jeff. "Understanding Creativity: What Drives us to Create?". Psychology of Beauty.

- ^ Jung, Carl (1964). "Approaching the Unconscious". In Jung, Carl; von Franz, Marie-Luise (eds.). Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books Ltd. pp. 18–103. ISBN 978-0385052214. OCLC 224253.

- ^ Jaffe, Aniela (1964). "Symbolism in the Visual Arts". In Jung, Carl; von Franz, Marie-Luise (eds.). Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books Ltd. pp. 230–271. ISBN 978-0385052214. OCLC 224253.

- ^ Griselda Pollock (ed.), Psychoanalysis and the Image. (Oxford: Blackwell. 2006).

- ^ Catherine de Zegher (ed.), Inside the Visible. (MIT Press, Boston, 1996)

- ^ Michael Podro The Critical Historians of Art (Yale University Press, 1982).

- ^ Dana Arnold and Margaret Iverson (eds.) Art and Thought. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2003.

- ^ "About Face: Perhaps its Not About What a Piece of Art Can Tell Us About the Artist's Type, but What Personality Theory Can Tell Us About What Art is". Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ a b c Sullivan, Paul; McCarthy, John (2009). "An experiential account of the psychology of art". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 3 (3): 181–187. doi:10.1037/a0014292.

- ^ a b c Sandelands, Lloyd E.; Buckner, Georgette C. "Of Art and Work: Aesthetic Experience and the Psychology of Work Feelings" (PDF). Research in Organizational Behavior. Vol. 11. pp. 105–131. ISBN 9780892329212. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lindell, Annukka K.; Mueller, Julia (1 June 2011). "Can science account for taste? Psychological insights into art appreciation". Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 23 (4): 453–475. doi:10.1080/20445911.2011.539556. S2CID 144923433.

- ^ a b c Solso, Robert L. (2003). The psychology of art and the evolution of the conscious brain. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. pp. 2–12. ISBN 978-0262194846.

- ^ Robinson-Riegler, Bridget Robinson-Riegler, Gregory (2012). Cognitive psychology : applying the science of the mind (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson Allyn & Bacon. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9780205033645.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Landau, Mark J.; Greenberg, Jeff; Solomon, Sheldon; Pyszczynski, Tom; Martens, Andy (1 January 2006). "Windows into Nothingness: Terror Management, Meaninglessness, and Negative Reactions to Modern Art". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 90 (6): 879–892. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.879. PMID 16784340.

- ^ a b c d e Proulx, T.; Heine, S. J.; Vohs, K. D. (5 May 2010). "When Is the Unfamiliar the Uncanny? Meaning Affirmation After Exposure to Absurdist Literature, Humor, and Art". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 36 (6): 817–829. doi:10.1177/0146167210369896. PMID 20445024. S2CID 16300370.

- ^ Nicki, R. M.; Moss, Virginia (1975). "Preference for non-representational art as a function of various measures of complexity". Canadian Journal of Psychology. 29 (3): 237–249. doi:10.1037/h0082029.

- ^ a b c d e Vartanian, Oshin; Goel, Vinod (2004). "Neuroanatomical correlates of aesthetic preference for paintings". NeuroReport. 15 (5): 893–897. doi:10.1097/00001756-200404090-00032. PMID 15073538. S2CID 7892067.

- ^ Batt, R; Palmiero, M; Nakatani, C; Van Leeuwen, C (11 June 2010). "Style and spectral power: Processing of abstract and representational art in artists and non-artists". Perception. 39 (12): 1659–1671. doi:10.1068/p6747. PMID 21425703. S2CID 36492643.

- ^ a b c Furnham, Adrian; Walker, John (2001). "Personality and judgments of abstract, pop art, and representational paintings". European Journal of Personality. 15 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1002/per.340. S2CID 143784122.

- ^ Mastandrea, Stefano; Bartoli, Gabriella; Carrus, Giuseppe (May 2011). "The Automatic Aesthetic Evaluation of Different Art and Architectural Styles". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 5 (2): 126–134. doi:10.1037/a0021126.

- ^ Maass, A; Russo, A (July 2003). "Directional bias in the mental representation of spatial events: nature or culture?". Psychological Science. 14 (4): 296–301. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.14421. PMID 12807400. S2CID 38484754.

- ^ Vaid, Jyotsna; Rhodes, Rebecca; Tosun, Sumeyra; Eslami, Zohra (2011). "Script Directionality Affects Depiction of Depth in Representational Drawings". Social Psychology. 42 (3): 241–248. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000068.

- ^ Chokron, Sylvie; De Agostini, Maria (2000). "Reading habits influence aesthetic preference". Cognitive Brain Research. 10 (1–2): 45–49. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(00)00021-5. PMID 10978691.

- ^ Nachson, I.; Argaman, E.; Luria, A. (1999). "Effects of Directional Habits and Handedness on Aesthetic Preference for Left and Right Profiles". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 30 (1): 106–114. doi:10.1177/0022022199030001006. S2CID 145410382.

- ^ Swartz, Paul; Hewitt, David (1970). "Lateral organization in pictures and aesthetic preference". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 30 (3): 991–1007. doi:10.2466/pms.1970.30.3.991. PMID 5429349. S2CID 6779326.

- ^ McDine, David A.; Livingston, Ian J.; Thomas, Nicole A.; Elias, Lorin J. (2011). "Lateral biases in lighting of abstract artwork". Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition. 16 (3): 268–279. doi:10.1080/13576500903548382. PMID 20544493. S2CID 29232403.

- ^ McLaughlin, John P.; Murphy, Kimberly E. (1994). "Preference for Profile Orientation in Portraits". Empirical Studies of the Arts. 12 (1): 1–7. doi:10.2190/MUD5-7V3E-YBN2-Q2XJ. S2CID 143763794.

- ^ ten Cate, Carel (2002). "Posing as Professor: Laterality in Posing Orientation for Portraits of Scientists". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 26 (3): 175–192. doi:10.1023/A:1020713416442. S2CID 189898809.

- ^ a b Conesa, Jorge; Brunold-Conesa, Cynthia; Miron, Maria (1995). "Incidence of the half-left profile pose in single-subject portraits". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 81 (3): 920–922. doi:10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.920. PMID 8668453. S2CID 29864266.

- ^ a b Conesa, J (1996). "Preference for the half-left profile pose: Three inclusive models". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 82 (3): 1070. doi:10.2466/pms.1996.82.3c.1070. PMID 8823872. S2CID 43784567.

- ^ Simon, H. A. (1996). The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- ^ Krupinski, E; Locher, P (1988). "Skin conductance and aesthetic evaluative responses to nonrepresentational works of art varying in symmetry". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 26 (4): 355–358. doi:10.3758/bf03337681.

- ^ a b Berlyne, D.E. (1971). Aesthetics and Psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. ISBN 9780390086709.

- ^ a b Orr, Mark; Ohlsson, Stellan (2005). "Relationship Between Complexity and Liking as a Function of Expertise". Music Perception. 22 (4): 583–611. doi:10.1525/mp.2005.22.4.583.

- ^ a b Zhang, K.; Harrell, S.; Ji, X. (2012). "Computational Aesthetics: On the Complexity of Computer-Generated Paintings". Leonardo. 45 (3): 243–248. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.310.2718. doi:10.1162/leon_a_00366. S2CID 57567595.

- ^ Neperud, Ronald; Marschalek (1988). "Informational and Affect Bases of Aesthetic Response". Leonardo. 21 (3): 305–31. doi:10.2307/1578660. JSTOR 1578660. S2CID 191383059.

- ^ a b c d Chamorro-Premuzic, T; Burke, C. (2010). "Personality Predictors of Artistic Preferences as a Function of Emotional Valence and Perceived Complexity of Paintings". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 4 (4): 196–204. doi:10.1037/a0019211.

- ^ a b c d North, A.C.; Hargreaves, D.J. (1995). "Subjective Complexity, Familiarity, and Liking for Popular Music". Psychomusicology. 14 (1–2): 77–93. doi:10.1037/h0094090.

- ^ Silvia, P. J. (2005). "What Is Interesting? Exploring the Appraisal Structure of Interest". Emotion. 5 (1): 89–102. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.576.692. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.89. PMID 15755222.

- ^ Forsythe, A; Nadal, M.; Sheehy, C.; Cela-Conde, C.; Sawey, M. (2011). "Predicting beauty: Fractal dimension and visual complexity in art" (PDF). British Journal of Psychology. 102 (1): 49–70. doi:10.1348/000712610X498958. PMID 21241285. S2CID 30077949.

- ^ Goodchilds, Jacqueline; Thornton B. Roby; Momoyo Ise (1969). "Evaluative reactions to the viewing of pseudo-dance sequences: Selected temporal and spatial aspects". The Journal of Social Psychology. 79 (1): 121–133. doi:10.1080/00224545.1969.9922395. PMID 5351780.

- ^ Hodgson, Derek (2011). "The First Appearance of Symmetry in the Human Lineage: Where Perception Meets Art". Symmetry. 3 (1): 37–53. Bibcode:2011Symm....3...37H. doi:10.3390/sym3010037.

- ^ a b Jones, B.; Lisa, D.M.; Little, A. (2007). "The role of symmetry in attraction to average faces". Perception & Psychophysics. 69 (8): 1273–1277. doi:10.3758/BF03192944. PMID 18078219.

- ^ Tinio, P. P. L.; Leder, H. (2009). "Just how stable are stable aesthetic features? Symmetry, complexity, and the jaws of massive familiarisation". Acta Psychologica. 130 (3): 241–250. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2009.01.001. PMID 19217589.

- ^ a b Rentschler, I; Jüttner, M; Unzicker, A; Landis, T (1999). "Innate and learned components of human visual preference". Current Biology. 9 (13): 665–671. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80306-6. PMID 10395537. S2CID 16067206.

- ^ a b c d e Makin, Alexis D. J.; Pecchineda, A.; Bertamini, M. (2012). "Implicit Affective Evaluation of Visual Symmetry". Emotion. 12 (5): 1021–1030. doi:10.1037/a0026924. hdl:11573/446772. PMID 22251051. S2CID 42313154.

- ^ a b c d Reber, Rolf; Schwarz, Norbert; Winkielman, Piotr (1 November 2004). "Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver's Processing Experience?". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8 (4): 364–382. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3. hdl:1956/594. PMID 15582859. S2CID 1868463.

- ^ a b c d e f Shepherd, Kathrine; Bar, Moshe (2011). "Preference for symmetry: Only on Mars?". Perception. 40 (10): 1254–1256. doi:10.1068/p7057. PMC 3786096. PMID 22308897.

- ^ a b c d e Cárdenas, R.A.; Harris, L.J. (2006). "Symmetrical decorations enhance the attractiveness of faces and abstract designs". Evolution and Human Behavior. 27: 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.05.002.

- ^ a b c d Friedenberg, Jay (May 2018). "Perceived beauty of elongated symmetric shapes: Is more better?". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 12 (2): 157–165. doi:10.1037/aca0000142. ISSN 1931-390X.

- ^ Washburn, D.; Humphrey, D. (2001). "Symmetries in the mind: Production, perception, and preference for seven one-dimensional patterns". Visual Arts Research. 27: 57–68.

- ^ a b Friedenberg, Jay (January 2018). "Geometric Regularity, Symmetry and the Perceived Beauty of Simple Shapes". Empirical Studies of the Arts. 36 (1): 71–89. doi:10.1177/0276237417695454. ISSN 0276-2374. S2CID 125543266.

- ^ a b c d e f Little, Anthony (17 April 2014). "Domain Specificity in Human Symmetry Preferences: Symmetry is Most Pleasant When Looking at Human Faces". Symmetry. 6 (2): 222–233. Bibcode:2014Symm....6..222L. doi:10.3390/sym6020222. ISSN 2073-8994.

- ^ a b c Swami, Viren; Furnham, Adrian (September 2012). "The Effects of Symmetry and Personality on Aesthetic Preferences". Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 32 (1): 41–57. doi:10.2190/IC.32.1.d. ISSN 0276-2366. S2CID 146541479.

- ^ a b Bertamini, Marco; Rampone, Giulia; Makin, Alexis D.J.; Jessop, Andrew (17 June 2019). "Symmetry preference in shapes, faces, flowers and landscapes". PeerJ. 7: e7078. doi:10.7717/peerj.7078. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6585942. PMID 31245176.

- ^ a b Leder, Helmut; Tinio, Pablo P. L.; Brieber, David; Kröner, Tonio; Jacobsen, Thomas; Rosenberg, Raphael (January 2019). "Symmetry Is Not a Universal Law of Beauty". Empirical Studies of the Arts. 37 (1): 104–114. doi:10.1177/0276237418777941. ISSN 0276-2374.

- ^ a b c d Weichselbaum, Hanna; Leder, Helmut; Ansorge, Ulrich (March 2018). "Implicit and Explicit Evaluation of Visual Symmetry as a Function of Art Expertise". i-Perception. 9 (2): 204166951876146. doi:10.1177/2041669518761464. ISSN 2041-6695. PMC 5937629. PMID 29755722.

- ^ Hu, Zhiguo; Wang, Xinrui; Hu, Xinkui; Lei, Xiaofang; Liu, Hongyan (February 2021). "Aesthetic Evaluation of Computer Icons: Visual Pattern Differences Between Art-Trained and Lay Raters of Icons". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 128 (1): 115–134. doi:10.1177/0031512520969637. ISSN 0031-5125. PMID 33121355. S2CID 226207439.

- ^ Gartus, Andreas; Völker, Mark; Leder, Helmut (May 2020). "What Experts Appreciate in Patterns: Art Expertise Modulates Preference for Asymmetric and Face-Like Patterns". Symmetry. 12 (5): 707. Bibcode:2020Symm...12..707G. doi:10.3390/sym12050707. ISSN 2073-8994.

- ^ Monteiro, Luis Carlos Pereira; Nascimento, Victória Elmira Ferreira do; Carvalho da Silva, Amanda; Miranda, Ana Catarina; Souza, Givago Silva; Ripardo, Rachel Coelho (February 2022). "The Role of Art Expertise and Symmetry on Facial Aesthetic Preferences". Symmetry. 14 (2): 423. Bibcode:2022Symm...14..423M. doi:10.3390/sym14020423. ISSN 2073-8994.

- ^ a b McMANUS, I. C. (October 2005). "Symmetry and asymmetry in aesthetics and the arts". European Review. 13 (S2): 157–180. Bibcode:2005EuRv...13S.157M. doi:10.1017/S1062798705000736. ISSN 1062-7987. S2CID 145809532.

- ^ Esaak, Shelley. "Balance". Education: Art History. About.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Sammartino, Jonathan; Palmer, Stephen E. (1 January 2012). "Aesthetic issues in spatial composition: Effects of vertical position and perspective on framing single objects". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 38 (4): 865–879. doi:10.1037/a0027736. PMID 22428674.

- ^ Locher, Paul; Overbeeke, Kees; Stappers, Pieter Jan (1 January 2005). "Spatial balance of color triads in the abstract art of Piet Mondrian". Perception. 34 (2): 169–189. doi:10.1068/p5033. PMID 15832568. S2CID 33551778.

- ^ Latto, Richard; Brain, Douglas; Kelly, Brian (1 January 2000). "An oblique effect in aesthetics: Homage to Mondrian (1872 - 1944)". Perception. 29 (8): 981–987. doi:10.1068/p2352. PMID 11145089. S2CID 6490395.

- ^ Locher, Paul J (1 October 2003). "An empirical investigation of the visual rightness theory of picture perception". Acta Psychologica. 114 (2): 147–164. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2003.07.001. PMID 14529822.

- ^ Vartanian, Oshin; Martindale, Colin; Podsiadlo, Jacob; Overbay, Shane; Borkum, Jonathan (1 November 2005). "The link between composition and balance in masterworks vs. paintings of lower artistic quality". British Journal of Psychology. 96 (4): 493–503. doi:10.1348/000712605X47927. PMID 16248938.

- ^ a b c d Silvia, P. J. (2007). "Knowledge-based assessment of expertise in the arts: exploring aesthetic fluency" (PDF). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 1 (4): 247–249. doi:10.1037/1931-3896.1.4.247.

- ^ a b c d Winston, W. S.; Cupchik, G. C. (1992). "The evaluation of high art and popular art by naive and experienced viewers". Visual Arts Research. 18 (1): 1–14. JSTOR 20715763.

- ^ Conesa, J; Brunold-Conesa, C; Miron, M (1995). "Incidence of the Half-Left Profile Pose in Single-Subject Portraits". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 81 (3): 920–922. doi:10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.920. PMID 8668453. S2CID 29864266.

- ^ Conesa-Sevilla, J.; et al. (1997). "Sex and differential hemispheric activation in directional and orientation preferences". Presented at the 77th Meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Tacoma, Washington.

- ^ Conesa-Sevilla, J. (April 2000). "Hemispheric activation and preference for the half-left profile". Presented at the Western Psychological Association. Portland, Oregon.

- ^ a b c d e f Pihko, E.; et al. (2011). "Experiencing art: the influence of expertise and painting abstraction level". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 5: 1–10. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00094. PMC 3170917. PMID 21941475.

- ^ a b c d e f Vogt, S.; S. Magnussen (2007). "Expertise in pictorial perception: eye-movement pattern and visual memory in artists and laymen". Perception. 36 (1): 91–100. doi:10.1068/p5262. PMID 17357707. S2CID 5910802.

- ^ a b c d e Leder, H.; G. Gerger; S. G. Dressler; A. Schabmann (2012). "How art is appreciated". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 6 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1037/a0026396.

- ^ a b c d e Hekkert, P.; Van Wieringen, P. C. (1996). "The impact of level of expertise on the evaluation of original and altered versions of post-impressionistic paintings". Acta Psychologica. 94 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1016/0001-6918(95)00055-0.

- ^ a b c Augustin, M. D.; Leder, H. (2006). "Art expertise: a study of concepts and conceptual spaces" (PDF). Psychology Science. 48 (2): 135–156. ISSN 1614-9947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Belke, B.; Leder, H.; Augustin, M.D. (2006). "Mastering style - effects of explicit style-related information, art knowledge and affective state on appreciation of abstract paintings" (PDF). Psychology Science. 48 (2): 115–134. ISSN 1614-9947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b Russell, Phil A. (1 February 2003). "Effort after meaning and the hedonic value of paintings". British Journal of Psychology. 94 (1): 99–110. doi:10.1348/000712603762842138. PMID 12648392.

- ^ a b Franklin, Margery B.; Becklen, Robert C.; Doyle, Charlotte L. (1 January 1993). "The Influence of Titles on How Paintings Are Seen". Leonardo. 26 (2): 103. doi:10.2307/1575894. JSTOR 1575894. S2CID 191412639.

- ^ Leder, Helmut; Carbon, Claus-Christian; Ripsas, Ai-Leen (1 February 2006). "Entitling art: Influence of title information on understanding and appreciation of paintings". Acta Psychologica. 121 (2): 176–198. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2005.08.005. PMID 16289075.

- ^ Yeazell, Ruth Bernard (April 2011). "This Is Not a Title". The Yale Review. 99 (2): 134–143. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9736.2011.00709.x.

- ^ Millis, Keith (1 September 2001). "Making meaning brings pleasure: the influence of titles on aesthetic experiences". Emotion. 1 (3): 320–329. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.320. PMID 12934689.

- ^ Alfirevic, Dj (2011). "Visual Expression in Architecture" (PDF). Arhitektura I Urbanizam. 31 (31): 3–15. doi:10.5937/arhurb1131003a.

- ^ Markovic, S.; Dj, Alfirevic (2015). "Basic dimensions of experience of architectural objects' expressiveness: Effect of expertise". Psihologija. 48 (1): 61–78. doi:10.2298/psi1501061m.

- ^ Rahmatabadi, Saeid; Toushmalani, Reza (2011). "Physical Order and Disorder in Expressionist Architecture Style" (PDF). Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 5 (9): 406–409. ISSN 1991-8178. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Bibliography[edit]

- Lev Vygotsky. The Psychology of Art. 1925 / 1965 / 1968 / 1971 / 1986 / 2004.

- Mark Jarzombek, The Psychologizing of Modernity. Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN

- Alan Ryan, John Dewey and the High Time of American Liberalism. W.W. Norton 1995, ISBN

- David Cycleback, Art Perception. Hamerweit Books, 2014

- Michael Podro, The Critical Historians of Art, Yale University Press, 1982. ISBN

Further reading[edit]

- Ellen Winner (2018). How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190863357.