Pilgrimage of Grace

| Pilgrimage of Grace | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European wars of religion | |||

A banner bearing the Holy Wounds of Jesus Christ, which was carried at the Pilgrimage of Grace | |||

| Date | October 1536 – February 1537 | ||

| Location | Yorkshire, England | ||

| Caused by | The English Reformation, dissolution of the monasteries, rising food prices, and Statute of Uses | ||

| Goals | The reversal of the Act of Supremacy, restoration of Mary Tudor to the line of succession, and removal of Thomas Cromwell | ||

| Resulted in | Suppression of the risings, execution of the leading figures | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular revolt beginning in Yorkshire in October 1536, before spreading to other parts of Northern England including Cumberland, Northumberland, Durham and north Lancashire, under the leadership of Robert Aske. The "most serious of all Tudor period rebellions", it was a protest against Henry VIII's break with the Catholic Church, the dissolution of the lesser monasteries, and the policies of the King's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, as well as other specific political, social, and economic grievances.[2]

Following the suppression of the short-lived Lincolnshire Rising of 1536, the traditional historical view portrays the Pilgrimage as "a spontaneous mass protest of the conservative elements in the North of England angry with the religious upheavals instigated by King Henry VIII". Historians have observed that there were contributing economic factors.[3]

Prelude to revolt[edit]

The 16th century[edit]

During the Tudor era there was a general rise in the population across England, concentrated in the areas around Yorkshire. This led to a series of enclosures of once common lands. With this increased competition for resources, lack of access to once common land, and a greater pool of labour available, it led to an increase in the price of goods while also leading to a lack of employment and therefore increased unrest amongst the population. [4]

In 1535, the year preceding the revolt, bad harvests led to a series of grain riots in Craven in June 1535 and Somerset in April 1536 where grain prices were 82% higher than those in 1534.[4]

Lincolnshire Rising and early riots[edit]

The Lincolnshire Rising was a brief rising against the separation of the Church of England from papal authority by Henry VIII and the dissolution of the monasteries set in motion by Thomas Cromwell. Both planned to assert the nation's religious autonomy and the king's supremacy over religious matters. The dissolution of the monasteries resulted in much property being transferred to the Crown.[5]

The royal commissioners seized not only land, but the church plate, jewels, gold crosses, and bells. Silver chalices were replaced by ones made of tin. In some instances these items had been donated by local families in thanksgiving for a perceived blessing or in memory of a family member. There was also resistance to the recently passed Statute of Uses, which sought to recover royal fees based on land tenure.[6] On 30 September 1536, Dr. John Raynes, Chancellor of the Diocese of Lincoln, and one of Cromwell's commissioners, was addressing the assembled clergy in Bolingbroke, informing them of the new regulations and taxes affecting them. One of his clerks further inflamed matters regarding new requirements for the academic standards of the clergy saying "Look to your books, or there will be consequences",[7] which may have worried some of the less educated attendees. Word of his discourse and rumours of confiscation spread rapidly throughout Lindsey and soon reached Louth and Horncastle.

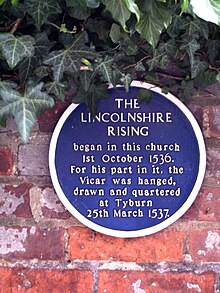

The rising began on 1 October 1536[2] at St James' Church, Louth, after Vespers, shortly after the closure of Louth Park Abbey. The stated aim of the uprising was to protest against the suppression of the monasteries, and not against the rule of Henry VIII himself.[6]

Led by a monk and a shoemaker called Nicholas Melton,[8] some 22,000 people are estimated to have joined the rising.[9] The rising quickly gained support in Horncastle, Market Rasen, Caistor, and other nearby towns. Dr. John Raynes, the chancellor of the Diocese of Lincoln, who was ill at Bolingbroke, was dragged from his sick-bed in the chantry priests' residence and later beaten to death by the mob, and the commissioners' registers were seized and burned.[6]

Angered by the actions of commissioners, the protesters demanded the end of the collection of a subsidy, the end of the Ten Articles, an end to the dissolution of religious houses, an end to taxes in peacetime, a purge of heretics in government, and the repeal of the Statute of Uses. With support from local gentry, a force of demonstrators, estimated at up to 40,000, marched on Lincoln and occupied Lincoln Cathedral. They demanded the freedom to continue worshipping as Roman Catholics and protection for the treasures of the Lincolnshire churches.[9]: 56

The protest effectively ended on 4 October 1536, when the King sent word for the occupiers to disperse or face the forces of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, which had already been mobilised. By 14 October, few remained in Lincoln. Following the rising, the vicar of Louth and Captain Cobbler, two of the main leaders, were captured and hanged at Tyburn.[5]

Most of the other local ringleaders were executed during the next 12 days, including William Moreland, or Borrowby, one of the former Louth Park Abbey monks.[10] Thomas Moigne, a lawyer from Willingham and one of the MPs for Lincoln, was hanged, drawn and quartered for his involvement.[5] The Lincolnshire Rising helped inspire the more widespread Pilgrimage of Grace.

Pilgrimage of Grace and the early Tudor crisis[edit]

"The Pilgrimage of Grace was a massive rebellion against the policies of the Crown and those closely identified with Thomas Cromwell."[11] The movement broke out on 13 October 1536, immediately following the failure of the Lincolnshire Rising. Only then was the term 'Pilgrimage of Grace' used. Historians have identified several key themes of the revolt:

Economic[edit]

The northern gentry had concerns over the new Statute of Uses. The poor harvest of 1535 had also led to high food prices, which likely contributed to discontent. The dissolution of the monasteries also affected the local poor, many of whom relied on them for food and shelter. Henry VIII was also in the habit of raising more funds for the crown through taxation, confiscation of lands, and depreciating the value of goods. A great deal of the taxation was levied against property and income, especially in the areas around Cumberland and Westmoreland where accounts of extortionate rents and gressums, a payment made to the crown when taking up a tenancy through inheritance, sale, or entry fines, were becoming more and more common.[12]

Political[edit]

Many people in England disliked the way in which Henry VIII had cast off his wife, Catherine of Aragon.[13] Although her successor, Anne Boleyn, had been unpopular as Catherine's replacement as a rumoured Protestant, her execution in 1536 on trumped-up charges of adultery and treason had done much to undermine the monarchy's prestige and the King's personal reputation. Aristocrats objected to the rise of Thomas Cromwell, who was "base born".[citation needed]

Religious[edit]

The local church was, for many in the north, the centre of community life. Many ordinary peasants were worried that their church plate would be confiscated. There were also popular rumours at the time which hinted that baptisms might be taxed. The recently released Ten Articles and the new order of prayer issued by the government in 1535 had also made official doctrine more Protestant, which went against the Catholic beliefs of most northerners.

Events[edit]

Robert Aske was chosen to lead the insurgents; he was a barrister from London, a resident of the Inns of Court, and the youngest son of Sir Robert Aske of Aughton, near Selby. His family was from Aske Hall, Richmondshire, and had long been in Yorkshire. In 1536, Aske led a band of 9,000 followers, each of whom had sworn the Oath of the Honourable Men, who entered and occupied York.[14][15] He arranged for expelled monks and nuns to return to their houses; the King's newly installed tenants were driven out, and Catholic observances were resumed.

The rising was so successful that the royalist leaders, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and George Talbot, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, opened negotiations with the insurgents at Scawsby Leys, near Doncaster, where Aske had assembled between 30,000 and 40,000 people.[16]

In early December 1536, the Pilgrimage of Grace gathered at Pontefract Castle to draft a petition to be presented to King Henry VIII with a list of their demands. The 24 Articles to the King, also called "The Commons' Petition", was given to the Duke of Norfolk to present to the king. The Duke promised to do so, and also promised a general pardon and a Parliament to be held at York within a year, as well as a reprieve for the abbeys until the Parliament had met. Accepting the promises, Aske dismissed his followers and the pilgrimage disbanded.[16]

Jesse Childs (a biographer of the Earl of Surrey, Norfolk's son) specifically notes that Henry VIII did not authorize Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, to grant remedies for the grievances. Norfolk's enemies had whispered into the King's ear that the Howards could put down a rebellion of peasants if they wanted to, suggesting that Norfolk sympathized with the Pilgrimage. Norfolk and the Earl of Shrewsbury were outnumbered: they had 5000 and 7000 respectively but there were 40,000 pilgrims. Upon seeing their vast numbers, Norfolk negotiated and made promises to avoid being massacred.[citation needed]

Suppression[edit]

In February 1537 there was a new rising (not authorised by Aske) in Cumberland and Westmorland, called Bigod's Rebellion, under Sir Francis Bigod, of Settrington in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Because he knew the promises he made on behalf of the King would not be met, Norfolk reacted quickly to the new uprising after the Pilgrims did not disperse as they had promised.

The rebellion failed and King Henry VIII arrested Bigod, Aske, and several other rebels, such as Darcy, John Hussey, 1st Baron Hussey of Sleaford, the Chief Butler of England; Sir Thomas Percy, and Sir Robert Constable. All were convicted of treason and executed. During 1537 Bigod was hanged at Tyburn; Lords Darcy and Hussey both beheaded; Thomas Moigne, M.P. for Lincoln was hanged, drawn, and quartered; Sir Robert Constable hanged in chains at Hull; and Robert Aske hanged in chains at York. In total 216 were executed: several lords and knights (including Sir Thomas Percy, Sir Stephen Hamerton, Sir William Lumley, Sir John Constable, and Sir William Constable), 7 abbots (Adam Sedbar, Abbot of Jervaulx, William Trafford, Abbot of Sawley, John Paslew, Abbot of Whalley, Matthew Mackarel, Abbot of Barlings and Bishop of Chalcedon, William Thirsk, Abbot of Fountains and the Prior of Bridlington), 38 monks, and 16 parish priests. Sir Nicholas Tempest, Bowbearer of the Forest of Bowland, was hanged at Tyburn, Sir John Bulmer hanged, drawn, and quartered and his wife Margaret Stafford burnt at the stake.

In late 1538, Sir Edward Neville, Keeper of the Sewer (official overseeing service), was beheaded. The loss of the leaders enabled the Duke of Norfolk to quell the rising,[16] and martial law was imposed upon the demonstrating regions. Norfolk executed some 216 activists (such as Lord Darcy, who tried to implicate Norfolk as a sympathizer): churchmen, monks, commoners.[17]

The details of the trial and execution of major leaders were recorded by the author of Wriothesley's Chronicle:[9]: 63-4 [18][2]

Also the 16-day of May [1537] there were arraigned at Westminster afore the King’s Commissioners, the Lord Chancellor that day being the chief, these persons following: Sir Robert Constable, knight; Sir Thomas Percy, knight, and brother to the Earl of Northumberland; Sir John Bulmer, knight, and Ralph Bulmer, his son and heir; Sir Francis Bigod, knight; Margaret Cheney, after Lady Bulmer by untrue matrimony; George Lumley, esquire;[19] Robert Aske, gentleman, that was captain in the insurrection of the Northern men; and one Hamerton, esquire, all which persons were indicted of high treason against the King, and that day condemned by a jury of knights and esquires for the same, whereupon they had sentence to be drawn, hanged and quartered, but Ralph Bulmer, the son of John Bulmer, was reprieved and had no sentence.

And on the 25-day of May, being the Friday in Whitsun week, Sir John Bulmer, Sir Stephen Hamerton, knights, were hanged and headed; Nicholas Tempest, esquire; Doctor Cockerell, priest;[20] Abbot quondam of Fountains;[21] and Doctor Pickering, friar,[22] were drawn from the Tower of London to Tyburn, and there hanged, bowelled and quartered, and their heads set on London Bridge and divers gates in London.

And the same day Margaret Cheney, 'other wife to Bulmer called', was drawn after them from the Tower of London into Smithfield, and there burned according to her judgment, God pardon her soul, being the Friday in Whitsun week; she was a very fair creature, and a beautiful.

Outcome[edit]

Failures[edit]

The Lincolnshire Rising and the Pilgrimage of Grace have historically been seen as failures for the following reasons:

- England was not reconciled to the Roman Catholic Church, except during the brief reign of Mary I (1553–1558).

- The dissolution of the monasteries continued unabated, with the largest monasteries being dissolved by 1540.

- Great tracts of land were seized from the Church and divided among the Crown and its supporters.

- The steps towards official Protestantism achieved by Cromwell continued, except during the reign of Mary I.

Successes[edit]

Their partial successes are less known:

- The government postponed the collection of the October subsidy, a major grievance amongst the Lincolnshire organisations.

- The Statute of Uses was partially negated by a new law, the Statute of Wills.

- Four of the seven sacraments that were omitted from the Ten Articles were restored in the Bishop's Book of 1537, which marked the end of the drift of official doctrine towards Protestantism. The Bishop's Book was followed by the Six Articles of 1539.

- An onslaught upon heresy was promised in a royal proclamation in 1538.

Leadership[edit]

Historians have noted the leaders among the nobility and gentry in the Lincolnshire Rising and the Pilgrimage of Grace and tend to argue that the Risings gained legitimacy only through the involvement of the northern nobility and gentlemen, such as Lord Darcy, Lord Hussey and Robert Aske.[23] However, historians such as M. E. James, C. S. L. Davies and Andy Wood, among others, believe the question of leadership was more complex.

James and Davies look at the Risings of 1536 as the product of common grievances. The lower classes were aggrieved because of the closure of local monasteries by the Act of Suppression. The northern nobility felt their rights were being taken away from them in the Acts of 1535–1536, which made them lose confidence in the royal government. James analysed how the lower classes and the nobility used each other as a legitimizing force in an extremely ordered society.

The nobles hid behind the force of the lower classes with claims of coercion, since they were seen as blameless for their actions because they did not possess political choice. This allowed the nobles an arena to air their grievances while, at the same time, playing the victims of popular violence. The lower classes used the nobility to give their grievance a sense of obedience since the "leaders" of the rebellion were of a higher social class.[24]

Davies considers the leadership of the 1536 Risings as more of a cohesion. Common grievances over evil advisors and religion brought the higher and lower classes together in their fight. Once the nobles had to confront the King's forces and an all-out war, they decided to surrender, thereby ending the cohesion.[25]

Historian Andy Wood, representing social historians of the late 20th century who have found more agency among the lower classes, argues that the commons were the effective force behind the Risings. He argues that this force came from a class group largely left out of history: minor gentlemen and well-off farmers. He believes these groups were the leaders of the Risings because they had more political agency and thought.[26]

List of executions[edit]

After the Lincolnshire Rising[edit]

- Richard Harrison, Abbot of Kirkstead Abbey

- Thomas Kendal, priest and vicar of Louth

- Matthew Mackerel, Premonstratensian abbot of Barlings Abbey, titular bishop of Chalcedon;

- Thomas Moigne (Moyne), gentleman

- William Moreland (aka Borowby), priest of Louth Park Abbey

- James Mallet, priest and chaplain to the late Queen Catherine

After the Pilgrimage[edit]

The sub-prior of the Augustinian Cartmel Priory and several of the canons were hanged, along with ten villagers who had supported them.[27] The monks of the Augustinian Hexham priory, who became involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace, were executed.

- 1537: George ab Alba Rose, Augustinian;

- George Ashby (Asleby), monk;[28]

- Ralph Barnes, monk;

- Laurence Blonham, monk;

- James Cockerell, Prior of Gisborough Priory;

- William Coe, monk;

- William Cowper, monk;

- John Eastgate, monk;

- Richard Eastgate, monk of Whalley Abbey; hanged 12 March 1537

- John Francis, monk;

- William Gylham, monk;

- William Haydock, monk of Whalley Abbey; hanged 13 March 1537

- Nicholas Heath, Prior of Lenton;

- John Henmarsh, priest;

- Robert Hobbes, Abbot of Woburn;

- Henry Jenkinson, monk;

- Richard Laynton, monk;

- Robert Leeche, layman;

- Hugh Londale, monk;

- John Paslew, Abbot of Whalley Abbey; hanged at Whalley

- 25 May 1537: John Pickering, priest;[29]

- Thomas Redforth, priest;

- 26 May 1537: Adam Sedbar, Abbot of Jervaulx;

- William Swale, monk;

- John Tenant, monk;

- Richard Wade, monk

Executed after Bigod's rebellion (1537)[edit]

- Robert Aske, layman;[30]

- Robert Constable, layman;

- The Lord Darcy de Darcy;[31]

- Sir Thomas Percy;

- John Pickering (friar);

- William Trafford, Abbot of Sawley; hanged at Lancaster 10 March 1537

- William Thyrsk (Thirsk), Cistercian former abbot of Fountains Abbey[29]

See also[edit]

- John Longland, Bishop of Lincoln during the period

- Prayer Book Rebellion

- Rising of the North

- Thomas Trahern, Somerset Herald, murdered in 1542 by William Leech of Fulletby, fugitive ringleader of the Lincolnshire rising

Citations[edit]

- ^ Crowther, David (7 January 2018). "The Pilgrimage of Grace II". The History of England Podcast. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Cross 2009.

- ^ Loades, David, ed. (2003). Reader's guide to British history. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 1039–41. ISBN 9781579582425.

- ^ a b Davies, C. S. L. (1968). "The Pilgrimage of Grace Reconsidered". Past & Present. 41 (41): 54–76. doi:10.1093/past/41.1.54. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 650003.

- ^ a b c Halpenny, Baron. "Lincolnshire Uprising – A Very Religious Affair". BBC Lincolnshire. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Gasquet, Francis Aidan. Henry VIII and the English Monasteries, G. Bell, 1906, p. 202

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ James, Mervyn (Mervyn Evans) (1986). Society, politics, and culture : studies in early modern England. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-521-25718-2. OCLC 12557775.

- ^ BBC. "Lincolnshire Uprising - A Very Religious Affair". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, William Douglas, ed. (1875). A Chronicle of England During the Reigns of the Tudors by Charles Wriothesley. London: Camden Society. pp. 56–64.

- ^ Page, William, ed. (1906). A History of the County of Lincoln: Volume 2. London: Victoria County History. pp. 138–141.

- ^ Loughlin, Susan. Insurrection: Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell and the Pilgrimage of Grace, Chapt 1, The History Press, 2016ISBN 9780750968768

- ^ Weightman, Peter John (2015). "The Role of the commons of Cumberland and Westmoreland in the Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536" (PDF). Department of Humanities, Northumbria University.

- ^ "The Divorce of Catherine of Aragon Book Chapter One". English History. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Bush, M. L.; Bownes, David (1999). The Defeat of the Pilgrimage of Grace: A Study of the Postpardon Revolts of December 1536 to March 1537 and Their Effect. University of Hull Press. ISBN 978-0-85958-679-5.

- ^ Fieldhouse, Raymond; Jennings, Bernard (1978). A History of Richmond and Swaledale. Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-247-6.

- ^ a b c

Burton, Edwin (1911). "Pilgrimage of Grace". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Burton, Edwin (1911). "Pilgrimage of Grace". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Childs, Jessie (2008). Henry VIII's last victim : the life and times of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. London: Vintage. p. 115. ISBN 9780712643474.

- ^ Dodds & Dodds 1915, p. 214.

- ^ Father of John Lumley, 1st Baron Lumley.

- ^ James Cockerell, Prior of Guisborough.

- ^ William Thirsk.

- ^ John Pickering of Bridlington.

- ^ Fletcher, Anthony; MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2015). Tudor Rebellions. Routledge. ISBN 9781317437376.

- ^ James, M. E. (August 1970). "Obedience and Dissent in Henrician England: The Lincolnshire Rebellion 1536". Past & Present (48): 68–76. JSTOR 650480.

- ^ Davies, C. S. L. (December 1968). "The Pilgrimage of Grace Reconsidered". Past & Present (41): 55–74. JSTOR 650003.

- ^ Wood, Andy (2002). Riot, rebellion and popular politics in early modern England. New York: Palgrave. pp. 19–54. ISBN 9780333637623.

- ^ "British History Online: The Priory of Cartmel". Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: George Ashby". Newadvent.org. 1 March 1907. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ a b "London Martyrs List.PDF" (PDF). Academic.regis.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Dodds & Dodds 1915, p. 225.

- ^ Dodds & Dodds 1915, p. 194.

General and cited references[edit]

- Cross, Claire (2009). "Participants in the Pilgrimage of Grace (act. 1536–1537)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 17 November 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Dodds, Madeleine Hope; Dodds, Ruth (1915). The Pilgrimage of Grace 1536–1537 and the Exeter Conspiracy 1538. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Still the major comprehensive history.

- Hamilton, William Douglas, ed. (1875). A Chronicle of England During the Reigns of the Tudors from A.D. 1485 to 1559 by Charles Wriothesley, Windsor Herald. Vol. I. London: J.B. Nichols and Sons.

- Knowles, David (1959). Bare Ruined Choirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521207126.

- Loades, David, ed. (2003). Reader's Guide to British History. pp. 1039–42.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pilgrimage of Grace". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Pilgrimage of Grace". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading[edit]

Nonfiction[edit]

- Hoyle, R.W. The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s (Oxford UP, 2001) 487 pp; scholarly study

- Geoffrey Moorhouse The Pilgrimage of Grace: The Rebellion That Shook Henry VIII's Throne. (2002) excerpt; popular non-fiction

- M. L. Bush, "The Tudor Polity and the Pilgrimage of Grace." Historical Research 2007 80(207): 47–72. online

Fiction[edit]

- John Buchan (1931). The Blanket of the Dark (Hodder and Stoughton, London), a novel;

- H. F. M. Prescott (1952). The Man on a Donkey, a novel

Hilary Mantel The Mirror & the Light (2020), a novel.

External links[edit]

- A summary of two historians' (Guy and Elton) perspectives on the Pilgrimages of Grace can be found at William Howard School

- HistoryLearningSite.co.uk – The Pilgrimage of Grace

- TudorPlace.com – The Pilgrimage of Grace (1536/7)

- Luminarium.com – Pilgrimage of Grace

- Hoyle, R. W. (2001). The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s. Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-19-925906-9.

- The Pilgrimage of Grace 1536—Henry VIII: Mind of a Tyrant series Web site