Peri

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

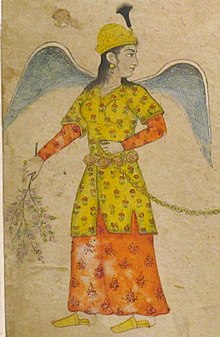

Peri, flying, with cup and wine flask. Miniature by Şahkulu. Freer Gallery of Art | |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Country | Iran |

Peris (singular: peri) are exquisite, winged spirits renowned for their beauty originating in Iranian mythology. Peris were later adopted by other cultures.[1] They are described in one reference work as mischievous beings that have been denied entry to paradise until they have completed penance for atonement.[2][need quotation to verify] Under Islamic influence, peris became benevolent spirits,[3] in contrast to the mischievous jinn and evil divs (demons). Scholar Ulrich Marzolph indicates an Indo-Iranian origin for peris,[4] which were later[when?] integrated into the Arab houri-tale tradition.

Etymology[edit]

The Persian word پَری parī comes from Middle Persian parīg, itself from Old Persian *parikā-.[5] The word may stem from the same root as the Persian word par 'wing',[6] although other proposed etymologies exist.[5] The word has been borrowed into Azerbaijani as pəri, into Hindustani as parī (Urdu: پری / Hindi: परी), and into Turkish as peri. It is etymologically unrelated to the English word fairy.[4]

In Persian mythology and literature[edit]

Peris are detailed in Persianate folklore and poetry, appearing in romances and epics. Furthermore, later poets use the term to designate a beautiful woman and to illustrate her qualities.

At the start of Ferdowsi's epic poem Shahnameh, "The Book of Kings", the divinity Sorush appears in the form of a peri to warn Keyumars (the mythological first man and shah of the world) and his son Siamak of the threats posed by the destructive Ahriman. Peris also form part of the mythological army that Keyumars eventually draws up to defeat Ahriman and his demonic son. In the Rostam and Sohrab section of the poem, Rostam's paramour, the princess Tahmina, is referred to as "peri-faced" (since she is wearing a veil, the term peri may include a secondary meaning of disguise or being hidden[dubious ]).

Peris were the target of a lower level of evil beings called دیوسان divs (دَيۋَ daeva), who persecuted them by locking them in iron cages.[7] This persecution was brought about by, as the divs perceived it, the peris' lack of sufficient self-esteem to join the rebellion against perversion.[2]

Turkish mythology[edit]

Parīs feature as Turkic mythological entities among other (Islamic or central Asian) creatures, such as jinn, ʿifrīt (fiends), nakir, and devils (šayāṭīn).[8] Kazakh shamans would sometimes consult parīs for aid.[9] Uyghur shamans are reported to use the aid of parīs to heal women from miscarriage, and protect from evil jinn.[10]

Parīs are attested in Turkish sources from the 11th century onward.[11] The term parī was probably associated with the Arabic jinn when entering the Turkic beliefs through Islamic sources.[12] Although jinn and parī are sometimes used as synonyms, the term parī is more frequently used in supernatural tales.[13] The parī are usually considered beneficent in Turkish sources,[14] though, in Kazakh tradition, they are sometimes considered to be malevolent jinn.[15] While the parī appear as complex figures in earlier Tatar poetry, in contemporary thought, they are usually merged into a single category with demons and devils.[16]

According to Turkologist Ignác Kúnos, the peris in Turkish tales fly through the air with their cloud-like garments of a green colour, but also in the shape of doves. They also number forty, seven or three, and serve a Peri-king that can be a human person they stole from the human realm. Like vestals, Kúnos wrote, the peris belong to the spiritual realm until love sprouts in their hearts, and they must join with their mortal lovers, being abandoned by their sisters to their own devices. Also, the first meeting between humans and peris occurs during the latter's bathtime.[17]

Islamic scripture and writings[edit]

With the spread of Islam through Persia, the peri was integrated into Islamic folklore. Early Persian translations of the Quran, identified jinn as peris, and devils with divs.[18][19] Hafez identified them with Houris.[6] According to Abu Ali Bal'ami's interpretation of the exegesis of the Qurʼan Tafsir al-Tabari, the peris are beautiful female spirits created by God after the vicious divs.[20] They mostly believe in God and are mostly benevolent to mankind.[21]

Marriage, although possible, is considered undue in Islamic lore. Because of humans' impatience and distrust, relationship between humans and peris will break up. Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba, is, according to one narrative, the daughter of such a failed relationship between a peri and a human.[22]

Today, they are still part of folklore and accordingly they are said to appear to humans, sometimes punishing hunters in the mountains who are disrespectful or waste resources, or even abducting young humans for their social events. Encounters with peris are held to be physical as well as psychological.[23]

The belief in peri still persist among Muslims in India as a type of spiritual creature besides the jinn, devils (shayatin) and the ghosts of the wicked (ifrit).[24]

Among Kho people, peri are believed to cast love spells, used by a spiritual master referred to as peri-khan (master of faries). They would live far from urban regions, having mastered the art of working with peris.[25]

Although peris are usually regarded as benevolent creatures, according to the book people of the air, they are credited with being morally ambivalent creatures, who could be either Muslims or infidels.[26]

Western representations[edit]

The character of the peri, as a supernatural wife, shares similar traits with the swan maiden, in that the human male hides the peri's wings and marries her. After some time, the peri woman regains her wings and leaves her mortal husband.[27]

The term peri appears in the early Oriental tale Vathek, by William Thomas Beckford, written in French in 1782.

In Thomas Moore's poem Paradise and the Peri, part of his Lalla-Rookh, a peri gains entrance to heaven after three attempts at giving an angel the gift most dear to God. The first attempt is "The last libation Liberty draws/From the heart that bleeds and breaks in her cause", to wit, a drop of blood from a young soldier killed for an attempt on the life of Mahmud of Ghazni. Next is a "Precious sigh/of pure, self-sacrificing love": a sigh stolen from the dying lips of a maiden who died with her lover of plague in the Mountains of the Moon (Ruwenzori) rather than surviving in exile from the disease and the lover. The third gift, the one that gets the peri into heaven, is a "Tear that, warm and meek/Dew'd that repentant sinner's cheek": the tear of an evil old man who repented upon seeing a child praying in the ruins of the Temple of the Sun at Balbec, Syria. Robert Schumann set Moore's tale to music as an oratorio, Paradise and the Peri, using an abridged German translation.

French composer Paul Dukas's ballet La Péri (1912) depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, finally encountering its guardian, the Peri.[28]

Gilbert and Sullivan's 1882 operetta Iolanthe is subtitled The Peer and the Peri. The "peris" in this work are also referred to as "fairies".

A peri, whose power is in her hair, appears in Elizabeth Ann Scarborough's 1984 novel The Harem of Aman Akbar.

In Lotte Reiniger's The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the titular character falls in love with a fairy queen named Pari Banu.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (2008). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Sharpe Reference. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-7656-8047-1.

- ^ a b Nelson, Thomas (1922). Nelson's New Dictionary of the English Language. Thomas Nelson & Sons. p. 234.

- ^ Aigle, Denise. The Mongol Empire between Myth and Reality: Studies in Anthropological History. BRILL, 28.10.2014. p. 118. ISBN 9789004280649.

- ^ a b Marzolph, Ulrich (08 Apr 2019). "The Middle Eastern World’s Contribution to Fairy-Tale History". In: Teverseon, Andrew. The Fairy Tale World. Routledge, 2019. pp. 46, 52, 53. Accessed on: 16 Dec 2021. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315108407-4 - "Turkish peri masalı is a literal translation of the term 'fairy tale,' the originally Indo–Persian character of the peri or pari constituting the equivalent of the European fairy in modern Persian folktales (Adhami 2010). [...] Probably the character most fascinating for a Western audience in the Persian tales is the peri or pari (Adhami 2010). Although the Persian word is tantalizingly close to the English 'fairy', both words do not appear to be etymologically related. English 'fairy' derives from Latin fatum, 'fate', via the Old French faerie, 'land of fairies'. The modern Persian word, instead, derives from the Avestan pairikā, a term probably denoting a class of pre-Zoroastrian goddesses who were concerned with sexuality and who were closely connected with sexual festivals and ritual orgies. In Persian narratives and folklore of the Muslim period, the peri is usually imagined as a winged character, most often, although not exclusively, of female sex, that is capable of acts of sorcery and magic (Marzolph 2012: 21–2). For the male hero, the peri exercises a powerful sexual attraction, although unions between a peri and a human man are often ill-fated, as the human is not able to respect the laws ruling the peri's world. The peri may at times use a feather coat to turn into a bird and is thus linked to the concept of the swan maiden that is wide-spread in Asian popular belief. If her human husband transgresses one of her taboos, such as questioning her enigmatic actions, the peri will undoubtedly leave him, a feature that is exemplified in the widely known European folktale tale type 400: 'The Man on a Quest for His Lost Wife' (Schmitt 1999)."

- ^ a b "PAIRIKĀ". Iranicaonline.org.

- ^ a b Boratav, P.N. and J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Parī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0886> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960-2007

- ^ Olinthus Gilbert Gregory Pantologia. A new (cabinet) cyclopædia, by J.M. Good, O. Gregory, and N. Bosworth assisted by other gentlemen of eminence, Band 8 Oxford University 1819 digitalized 2006 sec. 17

- ^ Yves Bonnefoy Asian Mythologies University of Chicago Press 1993 ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7 p. 322

- ^ Basilov, Vladimir N. "Shamanism in central Asia." The Realm of Extra-human. Agents and Audiences (1976): 149-157.

- ^ ZARCONE, EDITED BY THIERRY, and ANGELA HOBART. "AND ISLAM." The Sufi orders in northern Central Asia.

- ^ DAVLETSHİNA, Leyla, and Enzhe SADYKOVA. "ÇAĞDAŞ TATAR HALK BİLİMİNDEKİ KÖTÜ RUHLAR ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA: PERİ BAŞKA, CİN BAŞKA." Uluslararası Türk Lehçe Araştırmaları Dergisi (TÜRKLAD) 4.2 (2020): 366-374.

- ^ DAVLETSHİNA, Leyla, and Enzhe SADYKOVA. "ÇAĞDAŞ TATAR HALK BİLİMİNDEKİ KÖTÜ RUHLAR ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA: PERİ BAŞKA, CİN BAŞKA." Uluslararası Türk Lehçe Araştırmaları Dergisi (TÜRKLAD) 4.2 (2020): 366-374.

- ^ MacDonald, D.B., Massé, H., Boratav, P.N., Nizami, K.A. and Voorhoeve, P., “Ḏj̲inn”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0191> First published online: 2012 First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960-2007

- ^ Boratav, P.N. and J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Parī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0886. First published online: 2012. First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960-2007

- ^ Boratav, P.N. and J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Parī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0886. First published online: 2012. First print edition: ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4, 1960-2007

- ^ DAVLETSHİNA, Leyla, and Enzhe SADYKOVA. "ÇAĞDAŞ TATAR HALK BİLİMİNDEKİ KÖTÜ RUHLAR ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA: PERİ BAŞKA, CİN BAŞKA." Uluslararası Türk Lehçe Araştırmaları Dergisi (TÜRKLAD) 4.2 (2020): 366-374.

- ^ Kúnos, Ignác (1888). "Osmanische Volksmärchen I. (Schluss)". Ungarische Revue (in German). 8: 337.

- ^ https://iranicaonline.org/articles/genie-

- ^ Hughes, Patrick; Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1995). Dictionary of Islam. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120606722.

- ^ Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-1-5013-5420-5

- ^ Cosimo, Inc Arabian Nights, in 16 volumes: Volume XIII, Band 13 2008 ISBN 978-1-605-20603-5 page 256

- ^ Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall Rosenöl. Erstes und zweytes Fläschchen: Sagen und Kunden des Morgenlandes aus arabischen, persischen und türkischen Quellen gesammelt BoD – Books on Demand 9783861994862 p. 103 (German)

- ^ Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann Mills South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka Taylor & Francis, 2003 ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5 page 463

- ^ Frederick M. Smith The Self Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature and Civilization Columbia University Press 2012 ISBN 978-0-231-51065-3 page 570

- ^ Ferrari, Fabrizio M. (2011). Health and religious rituals in South Asia : disease, possession, and healing. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-83386-5. OCLC 739388185. p. 35-38

- ^ Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, Healing Rituals and Spirits in the Muslim World. (2017). Vereinigtes Königreich: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 148

- ^ Polish Fairy Tales. Translated from A. J. Glinski by Maude Ashurst Biggs. New York: John Lane Company. 1920. p. 96.

- ^ Blakeman, Edward (1990). Notes to Chandos CD 208852, p. 5

- Ferdowsi; Zimmern, Helen (trans.) (1883). "The Epic of Kings". Internet Sacred Text Archive. Retrieved October 18, 2011.