Operation Atlantic

| Operation Atlantic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle for Caen | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 Infantry divisions 1 Armoured Brigade | 2 Panzer divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,349–1,965 | Unknown | ||||||

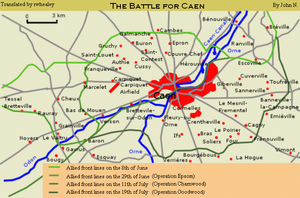

Operation Atlantic (18–21 July 1944) was a Canadian offensive during the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. The offensive, launched in conjunction with Operation Goodwood by the Second Army, was part of operations to seize the French city of Caen and vicinity from German forces. It was initially successful, with gains made on the flanks of the Orne River near Saint-André-sur-Orne but an attack by the 4th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, against strongly defended German positions on Verrières Ridge to the south was a costly failure.

Background[edit]

Operation Overlord[edit]

The capture of the historic Norman town of Caen, while "ambitious", was the most important D-Day objective assigned to British Lieutenant-General John Crocker's I Corps and its component British 3rd Infantry Division, which landed on Sword on 6 June 1944.[1][2][nb 1] Operation Overlord plans called for British Second Army to secure the city and form a line from Caumont-l'Éventé to the south-east of Caen, thus acquiring ground for airfields and protecting the left flank of the U.S. First Army, under Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley, as it moved on Cherbourg.[5] Possession of Caen and its surroundings would give Second Army jumping-off points to attack southwards and capture Falaise, which would in turn act as a pivot for a swing right to advance on Argentan and then the Touques River.[6] The terrain between Caen and Vimont was open, dry and conducive to swift offensive operations. Since the Allied forces greatly outnumbered the Germans in tanks and mobile units, a mobile battle was to their advantage.[7]

On D-Day the 3rd Division was unable to assault Caen in force and was brought to a halt north of the city.[8] Follow-up attacks failed as German resistance solidified. Operation Perch, a pincer attack by I and XXX Corps, began on 7 June, with the intention of encircling Caen from the east and west.[9] I Corps, striking south out of the Orne bridgehead, was halted by the 21st Panzer Division and the attack by XXX Corps bogged down in front of Tilly-sur-Seulles due to stout resistance by the Panzer-Lehr-Division.[9][10] In an effort to force the Panzer-Lehr to withdraw or surrender, and to keep operations fluid, the British 7th Armoured Division pushed through a recently created gap in the German front line to capture the town of Villers-Bocage.[11][12] The resulting day-long battle saw the vanguard of the British 7th Armoured Division withdraw from the town, but by 17 June Panzer-Lehr had been forced back and XXX Corps had taken Tilly-sur-Seulles.[13][14] Further offensive operations were postponed on 19 June, when a severe storm wracked the English Channel for three days, delaying the Allied build-up.[15]

On 26 June the British launched Operation Epsom, an attempt by Lieutenant-General Richard O'Connor's VIII Corps to outflank Caen's defenses by crossing the River Odon to the west of the city then circling eastward.[16][17] The attack was preceded by Operation Martlet, which secured VIII Corps' line of advance by capturing the high ground on their right.[18] The Germans managed to contain the offensive but were forced to commit all their armor, including two panzer divisions newly arrived in Normandy,[19][20] which forced them to cancel a planned offensive against British and American positions around Bayeux.[21] Several days later Second Army launched a new offensive, codenamed Operation Charnwood, against Caen.[22] Charnwood incorporated a postponed attack on Carpiquet, originally planned for Epsom as Operation Ottawa but now codenamed Operation Windsor.[23][24] In a frontal assault on 8–9 July the northern half of the city was captured.[22] German forces still held part of the city on the southern side of the Orne river, including the Colombelles steel works, a vantage point for artillery observers.[23]

Prelude[edit]

Plan[edit]

On 10 July General Bernard Montgomery, commander of all Allied ground forces in Normandy, held a meeting with Lieutenant-Generals Miles Dempsey and Omar Bradley, respectively the commanders of British Second Army and the United States First Army, at his headquarters to discuss the next attacks to be launched by 21st Army Group[25] following the conclusion of Operation Charnwood and the failure of the First Army's initial breakout offensive.[26] Montgomery approved Operation Cobra,[27] a major break out attempt to be launched by the First Army on 18 July, and ordered Dempsey to "go on hitting: drawing the German strength, especially the armour, onto yourself - so as to ease the way for Brad[ley]".[25]

Detailed planning for Operation Goodwood began on Friday 14 July.[28] On 15 July Montgomery issued a written order to Dempsey scaling back the operation. These new orders changed the operation from a "deep break-out to a limited attack".[29] The intention of the operation was now "to engage the German armour in battle and "write it down" to such an extent that it is of no further value to the Germans", and to improve the Second Army's position.[30] The orders stated that "a victory on the eastern flank will help us to gain what we want on the western flank" but warned that operations must not endanger Second Army's position, as it was a "firm bastion" that was needed for the success of American operations.[31] It was stressed that II Canadian Corps' objectives were now vital, and only following their completion would VIII Corps be free to " "crack about" as the situation demands".[31]

Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds' II Canadian Corps would launch an attack, codenamed Operation Atlantic, on the western flank of VIII Corps to liberate Colombelles and the remaining portion of Caen south of the Orne river.[32] Following the capture of these areas, the Corps was to be prepared to capture Verrières Ridge.[33] The Atlantic–Goodwood operation was slated to commence on 18 July, two days before the planned start of Operation Cobra.[34]

Preparations for Atlantic were delegated to General Simonds, in his first action as the commander of II Canadian Corps.[35] He planned the operation as a two-pronged assault, relying on the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions to capture Vaucelles, Colombelles, and the opposite banks of the Orne River.[35] On the morning of 18 July, Gen. Rod Keller's 3rd Division would cross the Orne near Colombelles, and then proceed south towards Route Nationale 158.[35] The 3rd Division would then move to capture Cormelles.[36] The 2nd Division, under the command of Gen. Charles Foulkes, would attack from Caen to the south-east, crossing the Orne to capture the outskirts of Vaucelles. They would then use Cormelles as a jumping-off point for an attack on the high ground near Verrières Ridge three miles to the south.

Battle[edit]

On the morning of 18 July, with heavy air support, advance elements of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division were able to capture Colombelles and Faubourg-de-Vaucelles, a series of industrial suburbs just south of Caen along the Orne River. By mid-afternoon, two companies of the Black Watch had crossed the Orne River, with 'A' Company taking fewer than twenty casualties.[37] Additional Battalions from 5th Brigade managed to push southward to Saint-André-sur-Orne.[38] With the east bank of the Orne River secured, the 4th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades moved into position for the assault on Verrières Ridge.[39]

The German High Command (OKW) had not missed the strategic importance of the ridge. Though nowhere more than 90 ft (27 m) high, it dominated the Caen–Falaise road, blocking Allied forces from breaking out into the open country south of Caen. The 1st SS Panzer Corps (Sepp Dietrich) and parts of the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, defended the area, amply provided with artillery, nebelwerfer and tanks.[38]

Units of the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, supporting the South Saskatchewan Regiment of the 2nd Division, were able to secure a position in St. André-sur-Orne in the early hours of 20 July but were soon pinned down by German infantry and tanks.[40] A simultaneous direct attack up the slopes of Verrières Ridge by the South Saskatchewans fell apart as heavy rain prevented air support and turned the ground to muck, making it difficult for tanks to maneuver. Counterattacks by two Panzer divisions forced the South Saskatchewans back past their start line and crashed into their supporting battalion, the Essex Scottish,[41] who lost over 300 men as they struggled to hold back the 1st SS Panzer Division. Meanwhile, to the east, the remainder of I SS Panzer Corps fought the largest armored battle of the campaign, with British forces involved in Operation Goodwood.[42] By the end of the day, the South Saskatchewan Regiment had taken 282 casualties and the ridge was still in enemy hands.

Simonds remained determined to take the ridge. He sent in two battalions, the Black Watch and the Calgary Highlanders, to stabilize the situation, and minor counterattacks by both, on 21 July, managed to contain Dietrich's armored formations. By the time the operation was called off, Canadian forces held several footholds on the ridge, including a now secure position on Point 67. Four German divisions still held the ridge. In all, the actions around Verrières Ridge during Operation Atlantic accounted for over 1,300 Allied casualties.[41]

Aftermath[edit]

Analysis[edit]

Caen south of the Orne was captured, but the failure to seize Verrières Ridge led Montgomery to issue orders on 22 July for another offensive, this time to be a "holding attack", within a few days, in conjunction with Operation Cobra.[43] As a result, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds formulated the plans for Operation Spring. The contemporaneous Battle of Verrières Ridge claimed over 2,600 Canadian casualties by the end of 26 July.[44]

Casualties[edit]

The Canadian official historian, C. P. Stacey, gave Canadian casualties in all services of 1,965 men, 441 of whom were killed or died of wounds.[45] Copp recorded from 1,349–1,965 Canadian casualties in Operation Atlantic, the majority in the 4th and 6th Canadian Infantry Brigades.[44][45][46]

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "The quick capture of that key city Caen and the neighbourhood of Carpiquet was the most ambitious, the most difficult and the most important task of Lieutenant-General J.T. Crocker's I Corps".[2] Wilmot states "The objectives given to Crocker's seaborne divisions were decidedly ambitious, since his troops were to land last, on the most exposed beaches, with the farthest to go, against what was potentially the greatest opposition."[3] However Miles C. Dempsey, commanding the British Second Army, always considered the possibility that the immediate seizure of Caen might fail.[4]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Williams, p. 24

- ^ a b Ellis, p. 171

- ^ Wilmot, p. 273

- ^ Buckley, p. 23

- ^ Ellis, p. 78

- ^ Ellis, p. 81

- ^ Van-Der-Vat, p. 146

- ^ Wilmot, pp. 284–286

- ^ a b Forty, p. 36

- ^ Ellis, pp. 247–250

- ^ Ellis, p. 254

- ^ Taylor, p. 10

- ^ Forty, p. 97

- ^ Taylor, p. 76

- ^ Williams, p. 114

- ^ Clark, pp. 31–32

- ^ Clark, pp. 32–33

- ^ Clark, p. 21

- ^ Hart, p. 108

- ^ Reynolds (2002), p. 13

- ^ Wilmot, p. 334

- ^ a b Williams, p. 131

- ^ a b Stacey, p. 150

- ^ Jackson, p. 60

- ^ a b Trew, p. 49

- ^ Wilmot, p. 351

- ^ Williams, p. 175

- ^ Jackson, p. 79

- ^ Trew, p. 66

- ^ Ellis, pp. 330–331

- ^ a b Ellis, p. 331

- ^ Stacey, p. 169

- ^ Stacey, pp. 170–171

- ^ Williams, p. 161

- ^ a b c Bercuson, p. 222

- ^ Roy, p. 68

- ^ Copp, The Approach to Verrières Ridge

- ^ a b Copp, Approach to Verrières Ridge

- ^ Jarymowycz, Pg. 3

- ^ Bercuson, p. 220

- ^ a b Zuehlke, Pg. 166

- ^ Bercuson, p. 223

- ^ Copp, Approach to Verrières Ridge p.

- ^ a b Zuehlke, Pg. 166

- ^ a b Stacey, p. 176

- ^ Copp, p. 5

References[edit]

- Bercuson, D. (2004) [1996]. Maple leaf Against the Axis. Markham Ontario: Red Deer Press. ISBN 978-0-88995-305-5.

- Copp, T. (1992). "Fifth Brigade at Verrières Ridge". Canadian Military History. 1 (1–2): 45–63. ISSN 1195-8472. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Copp, T. (1999). "The Toll of Verrières Ridge". Legion Magazine (May/June 1999). Ottawa: Canvet Publications. ISSN 1209-4331. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Jarymowycz, R. (2001). Tank Tactics, from Normandy to Lorraine. Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Jarymowycz, R. "Der Gegenangriff vor Verrières: German Counter-attacks during Operation "Spring", 25–26 July 1944". Canadian Military History (PDF). 2 (1). Waterloo Ontario: Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies. ISSN 1195-8472. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- Scislowski, S. (1999). "Verrières Ridge: A Canadian Sacrifice". Maple Leaf Up. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- van-der-Vat, D. (2004). D-Day, the Greatest Invasion, a People's History. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-58234-314-4.

- Zuehlke, M. (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas. Toronto: Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-3289-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Stacey, C. P.; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. III. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. OCLC 606015967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-20.