Notorious (1946 film)

| Notorious | |

|---|---|

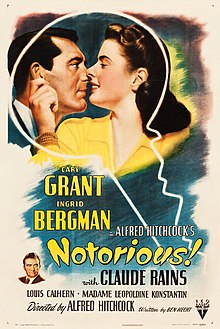

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Written by | Ben Hecht |

| Produced by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Starring | Cary Grant Ingrid Bergman Claude Rains Louis Calhern Leopoldine Konstantin |

| Cinematography | Ted Tetzlaff |

| Edited by | Theron Warth |

| Music by | Roy Webb |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[2] |

| Box office | $24.5 million[3] |

Notorious is a 1946 American spy film noir directed and produced by Alfred Hitchcock, starring Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains as three people whose lives become intimately entangled during an espionage operation.

The film follows U.S. government agent T.R. Devlin (Grant), who enlists the help of Alicia Huberman (Bergman), the daughter of a German war criminal, to infiltrate a circle of executives of IG Farben hiding out in Rio de Janeiro after World War II. The situation becomes complicated when the two fall in love as Huberman is instructed to seduce Alex Sebastian (Rains), a Farben executive who had previously been infatuated with her. It was shot in late 1945 and early 1946, and was released by RKO Radio Pictures in August 1946.

Notorious is considered by critics and scholars to mark a watershed for Hitchcock artistically, and to represent a heightened thematic maturity. His biographer, Donald Spoto, writes that "Notorious is in fact Alfred Hitchcock's first attempt—at the age of forty-six—to bring his talents to the creation of a serious love story, and its story of two men in love with Ingrid Bergman could only have been made at this stage of his life."[4] In 2006, Notorious was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot[edit]

In April 1946, Alicia Huberman, the American daughter of a convicted Nazi spy, is recruited by government agent T. R. Devlin to infiltrate an organization of Nazis who have escaped to Brazil after World War II. When Alicia refuses to help the authorities, Devlin plays recordings of her fighting with her father and insisting that she loves America.

While awaiting the details of her assignment in Rio de Janeiro, Alicia and Devlin fall in love, though his feelings are complicated by his knowledge of her promiscuous past. When Devlin gets instructions to persuade her to seduce Alex Sebastian, one of her father's friends and a leading member of the Farben executives, Devlin fails to convince his superiors that Alicia is not fit for the job. Devlin is also informed that Sebastian once was in love with Alicia. Devlin puts up a stoic front when he informs Alicia about the mission. Alicia infers, mistakenly, that he was merely pretending to love her as part of his job.

Devlin contrives to have Alicia meet Sebastian at a riding club. He recognizes her and invites her to dinner where he says that he always knew they would be reunited. Sebastian quickly invites Alicia to dinner the following night at his home, where he will host a few business acquaintances. Devlin and Captain Paul Prescott of the US Secret Service tell Alicia to memorize the names and nationalities of everyone there. At dinner, Alicia notices that a guest becomes agitated at the sight of a certain wine bottle, and is ushered quickly from the room. When the gentlemen are alone at the end of the dinner, this guest apologizes and tries to go home, but another insists on driving him, implying that he will kill him.

Soon Alicia reports to Devlin, "You can add Sebastian's name to my list of playmates." When Sebastian proposes, Alicia informs Devlin; he coldly tells her to do whatever she wants. Deeply disappointed, she marries Sebastian.

After she returns from her honeymoon, Alicia is able to tell Devlin that the key ring her husband gave her lacks the key to the wine cellar. Devlin suggests that Alicia give a grand party and invite him, so he can investigate. Alicia secretly steals the key from Sebastian's ring, and Devlin and Alicia search the cellar. Devlin accidentally breaks a bottle; inside is black sand, later proven to be uranium ore. Devlin takes a sample, cleans up, and locks the door as Sebastian comes down for more champagne. Sebastian is shocked and dismayed to see the two of them alone together. Devlin pretends to be drunk and tells Sebastian that in his drunken state he insisted that Alicia come down to the cellar with him. She confirms this story and adds that she acquiesced in order to prevent Devlin from making an embarrassing scene in front of the party guests. Devlin congratulates Sebastian on having won Alicia's love and respect, and makes an exit.

Sebastian realizes that the cellar key is missing from his key ring, but the next morning he sees that Alicia has reattached it during the night. Thoroughly alarmed, he returns to the cellar and finds the glass and sand from the broken bottle.

Now Sebastian has a problem: he must silence Alicia, but cannot expose her without revealing his own blunder to the rest of the Nazi emigres, who will certainly kill him if they learn that he has married an American agent. When Sebastian discusses the situation with his mother, she suggests that Alicia "die slowly" by poisoning. They poison her coffee and she soon falls ill. Her illness worsens until she collapses and is taken to her room, where the telephone has been removed. Too weak to leave, she perceives that her husband is slowly poisoning her to death.

Devlin, alarmed by Alicia's continuing absence, sneaks into Alicia's room, where she tells him that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Shocked into honesty by Alicia's peril, he finally confesses his love for her, and carries her out of the mansion in full view of Sebastian's co-conspirators. Sebastian and his mother go along with Devlin's story that Alicia must go to the hospital, but the conspirators are not convinced. Outside, Sebastian begs Devlin and Alicia to take him with them, but they contemptuously drive away, leaving him behind to suffer a grim fate at the hands of his fellow Nazis.

Cast[edit]

- Cary Grant as T. R. Devlin

- Ingrid Bergman as Alicia Huberman

- Claude Rains as Alexander Sebastian

- Leopoldine Konstantin as Madame Anna Sebastian

- Louis Calhern as Captain Paul Prescott, an officer of the U.S. Secret Service

- Reinhold Schünzel as Dr. Anderson, a Nazi conspirator

- Moroni Olsen as Walter Beardsley, another Secret Service officer

- Ivan Triesault as Eric Mathis, a Nazi conspirator

- Alexis Minotis as Joseph, Sebastian's butler (billed as Alex Minotis)

- Wally Brown as Mr. Hopkins

- Sir Charles Mendl as Commodore

- Ricardo Costa as Dr. Julio Barbosa

- Eberhard Krumschmidt as Emil Hupka, a Nazi conspirator

- Fay Baker as Ethel

- Bea Benaderet as File Clerk (uncredited)

- Peter von Zerneck as Wilhelm Rossner, a Nazi conspirator (uncredited)

- Friedrich von Ledebur as Knerr, a Nazi conspirator (uncredited)

Cast notes[edit]

Biographer Patrick McGilligan writes that "Hitchcock rarely managed to pull together a dream cast for any of his 1940s films, but Notorious was a glorious exception."[5] Indeed, with a story of smuggled uranium as a backdrop, "[t]he romantic pairing of Grant and Bergman promised a box office bang comparable to an atomic blast."[6]

Not everyone saw it that way, however, most notably the project's original producer David O. Selznick. After he sold the property to RKO to raise some quick cash, Selznick lobbied hard to get Grant replaced with Joseph Cotten. The U.S. had just dropped atomic bombs on Japan; Selznick argued that the first film out about atomic weaponry would be the most successful and Grant was not available for three months.[7] Selznick also believed Grant would be difficult to manage and make high salary demands,[8] but most telling of all — Selznick owned Cotten's contract.[7] Hitchcock and RKO production executive William Dozier invoked a clause in the project sale contract and blocked Selznick's attempts; Grant was signed to play opposite Bergman by late August 1945.[9]

Hitchcock had wanted Clifton Webb to play Alexander Sebastian.[10] Selznick pressed for Claude Rains in typical Selznick memo-heavy style: "Rains offers 'an opportunity to build the gross of Notorious enormously... . [D]o not lose a day trying to get the Rains' deal nailed down.'"[11] Whether they were thinking in Selznick's box office terms or in more artistic ones, Dozier and Hitchcock agreed, and Rains' performance transformed Sebastian into a classic Hitchcock villain: sympathetic, nuanced, in some ways as admirable as the protagonist.[10] The final major casting decision was Mme. Sebastian, Alex's mother. "The spidery, tyrannical Nazi matron demanded a stronger, older presence",[10] and when attempts to obtain Ethel Barrymore and Mildred Natwick fell through, German actor Reinhold Schünzel suggested Leopoldine Konstantin to Hitchcock and Dozier. Konstantin had been one of pre-war Germany's greatest actresses.[10] Notorious was Konstantin's only American film appearance, and "one of the unforgettable portraits in Hitchcock's films".[10]

Alfred Hitchcock's cameo appearance, a signature occurrence in his films, takes place at the party in Sebastian's mansion. At 1:04:43 (1:01:50 on European DVDs and 64:28 of the edited cut) into the film, Hitchcock is seen drinking a glass of champagne as Grant and Bergman approach. He sets his glass down and quickly departs.

Production[edit]

Pre-Production[edit]

Notorious started life as a David O. Selznick production, but by the time it hit American screens in August 1946, it bore the RKO studio's logo. Alfred Hitchcock became the producer, but as on all his subsequent films, he limited his screen credits to "Directed by" and his possessive credit above the title.

Its first glimmer occurred some two years previously, in August 1944, over lunch between Hitchcock and Selznick's story editor, Margaret McDonell. Her memo to Selznick said that Hitchcock was "very anxious to do a story about confidence tricks on a grand scale [with] Ingrid Bergman [as] the woman ... Her training would be as elaborate as the training of a Mata Hari."[12] Hitchcock continued his conversation a few weeks later, this time dining at Chasen's with William Dozier, an RKO studio executive, and pitching it as "the story of a woman sold for political purposes into sexual enslavement".[13] By this time, he had one of the single-word titles he preferred: Notorious.[14] The pitch was convincing: Dozier quickly entered into talks with Selznick, offering to buy the property and its personnel for production at RKO.

Dozier's interest rekindled Selznick's, which up to that point had only been tepid. Perhaps what started Hitchcock's mind rolling was "The Song of the Dragon", a short story by John Taintor Foote which had appeared as a two-part serial in the Saturday Evening Post in November 1921; Selznick, who owned the rights to it, had passed it on to Hitchcock from his unproduced story file during the filming of Spellbound.[13] Set during World War I in New York, "The Song of the Dragon" told the tale of a theatrical producer approached by federal agents, who want his assistance in recruiting an actress he once had a relationship with to seduce the leader of a gang of enemy saboteurs.[15] Although the story was a nominal starting point that "offered some inspiration, the final narrative was pure Hitchcock".[16]

Hitchcock travelled to England for Christmas 1944, and when he returned, he had an outline for Selznick's perusal.[13] The producer approved development of a script, and Hitchcock decamped for Nyack, New York, for three weeks of collaboration with Ben Hecht, whom he had just worked with on Spellbound. The two would work at Hecht's house, with Hitchcock repairing at night to the St. Regis New York. The two had an extraordinarily smooth and fruitful working partnership, partly because Hecht did not really care how much Hitchcock rewrote his work:[13]

Their story conferences were idyllic. Mr. Hecht would stride about or drape himself over chair or couch, or sprawl artistically on the floor. Mr. Hitchcock, a 192-pound Buddha (reduced from 295) would sit primly on a straight-back chair, his hands clasped across his midriff, his round button eyes gleaming. They would talk from nine to six; Mr. Hecht would sneak off with his typewriter for two or three days; then they would have another conference. The dove of peace lost not a pinfeather in the process.[17]

Hitchcock delivered his and Hecht's screenplay to Selznick in late March, but the producer was getting drawn deeper into the roiling problems of his western epic Duel in the Sun. At first he ordered story conferences at his home, typically with start times of eleven p.m.,[18] to both Hecht's and Hitchcock's profound annoyance. The two would dine at Romanoff's and "pool their defenses about what Hitchcock thought was a first class script".[18] Shortly, though, Duel's problems won out and Selznick relegated Notorious to his mental back burner.

Among the many changes to the original story was the introduction of a MacGuffin: a cache of uranium being held in Sebastian's wine cellar by the Nazis. At the time, it was not common knowledge that uranium was being used in the development of the atomic bomb, and Selznick had trouble understanding its use as a plot device. Indeed, Hitchcock later claimed he was followed by the FBI for several months after he and Hecht discussed uranium with Robert Millikan at Caltech in mid-1945.[19] In any event, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the release of details of the Manhattan Project, removed any doubts about its use.[20]

By June 1945, Notorious reached its turning point. Selznick "was losing faith in a film that never really interested him";[8] the MacGuffin still bothered him, as did the Devlin character, and he worried that audiences would dislike the Alicia character.[8] More worrisome, though, was the drain on his cash reserves imposed by the voracious Duel in the Sun. Finally, he agreed to sell the Notorious package to RKO: script, Bergman and Hitchcock.

The deal was a win-win-win situation: Selznick got $800,000 cash, plus 50% of the profits, RKO obtained a prestige production with an ascendant star and an emerging director, and Hitchcock, though he received no money, did escape from under Selznick's stifling thumb.[9] He also got to be his own producer for the first time, an important step for him: "supervising everything from the polishing of the script to the negotiation of myriad post-production details, the director could demonstrate to the industry at large his skill as an executive."[9] RKO assumed the project in mid-July 1945, and furnished office space, studio space, distribution—and freedom.

There was no getting away from Selznick completely, though. He contended that his 50% stake in the profits still entitled him to input into the project. He still dictated sheaves of memos about the script, and tried to oust Cary Grant from the cast in favor of his contractee, Joseph Cotten.[7] When the United States detonated two atomic bombs over Japan in August, the memos commenced anew and centered mainly on Selznick's continuing dissatisfaction with the script. Hitchcock was abroad,[7] so Dozier called on playwright Clifford Odets, who previously wrote None But the Lonely Heart for RKO and Grant, to do a rewrite. With Hitchcock and Selznick both busy, Selznick's script assistant Barbara Keon would be his only contact.

Odets's script tried to bring more atmosphere to the story than had previously been present. "Extending the characters' emotional range, he heightened the passion of Devlin and Alicia and the aristocratic ennui of Alex Sebastian. He also added a soupçon of high culture to soften Alicia: She quotes French poetry from memory and sings Schubert."[7] But his draft did nothing for Selznick, who still thought the characters lacked dimension, that Devlin still lacked charm, and that the couple's sleeping together "may cheapen her in the eyes of the audience".[21] Ben Hecht's appraisal, handwritten in the margin, was straightforward: "This is really loose crap."[21] In the end, the Odets script was a blind alley: Hitchcock apparently used none of it.[17]

What he did have in his hand, though, was the script for "... a consummate Hitchcock film, in every sense filled with passion and textures and levels of meaning".[22]

Production[edit]

Principal photography for Notorious began on October 22, 1945[22] and wrapped in February 1946.[10] Production was structured the way Hitchcock preferred it: with almost all shooting done indoors, on RKO sound stages, even seeming "exterior" scenes achieved with rear projection process shots. This gave him maximum control of his filmmaking through the day; in the evenings he exercised similar control over the nightly soirées at his Bellagio Road home.[23] The only scene requiring outdoor filming was the one at the riding club where Devlin and Alicia contrive to meet Alexander Sebastian on horseback; this scene was shot at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden in Arcadia, California. Second unit crews shot establishing exteriors and rear-projection footage in Miami, Rio de Janeiro and at the Santa Anita Park racetrack.

With everything stage-bound, production was smooth and problems were few, and small—for instance, Claude Rains, who stood three or four inches shorter than Ingrid Bergman.[22] "[There's] this business of you being a midget with a wife, Miss Bergman, who is very tall", the director kidded with Rains, a good friend. For the scenes where Rains and Bergman were to walk hand-in-hand, Hitchcock devised a system of ramps that boosted Rains's height yet were unseen by the camera.[24] He also suggested Rains try elevator shoes: "Walk in them, sleep in them, be comfortable in them."[24] Rains did, and used them thereafter. Hitchcock gave Rains the choice of playing Sebastian with a German or his English accent; Rains chose the latter.

Ingrid Bergman's gowns were by Edith Head,[1] in one of her many collaborations with Hitchcock.

One of the signature scenes in Notorious is the two-and-a-half-minute kiss that Hitchcock interrupted every three seconds to slip the scene through the three-second-rule crack in the Production Code. "The two stars worried about how strange it felt", writes biographer McGilligan. "Walking along, nuzzling each other with the camera trailing behind them, seemed 'very awkward' to the actors during filming, according to Bergman. 'Don't worry', Hitchcock assured her. 'It'll look right on the screen.'"[25]

Although the production proceeded smoothly it was not without some unusual aspects. The first was the helpfulness of Cary Grant toward Ingrid Bergman, in a way that "was remarkably calm and pointedly unusual for him".[26] Although this was Bergman's second outing with Hitchcock (the first was the just-finished Spellbound), she was nervous and insecure early on. The often moody, sometimes withdrawn[24] Grant, though, "came to Notorious full of bounce"[24] and coached her through her initial period of adjustment, rehearsing her the way Devlin rehearses Alicia.[24] This began a lifetime friendship for the two.

There were two passionate turmoils going on on-set, and both served to inform the final product: one was Hitchcock's growing infatuation with Bergman, and the other was her torturous affair with Robert Capa, the celebrity battlefield photographer.[27] As a result of this simpatico connection, and "to accomplish the deepest logic of Notorious, Hitchcock did something unprecedented in his career: he made Ingrid his closest collaborator on the picture":[27]

"The girl's look is wrong", Ingrid said to Hitchcock when, after several takes of her close-up during the dinner sequence, everyone knew something was awry. "You have her registering [surprise] too soon, Hitch. I think she would do it this way." And with that, Ingrid did the scene her way. There was not a sound on the set, for Hitchcock did not suffer actors' ideas gladly: he knew what he wanted from the start. Well before filming began, every eventuality of every scene had been planned—every camera angle, every set, costume, prop, even the sound cues had been foreseen and were in the shooting script. But in this case, an actress had a good idea, and to everyone's astonishment, he said, "I think you're right, Ingrid."[28]

When production wrapped in February 1946, Hitchcock had in the can what François Truffaut later told him "gets a maximum of effect from a minimum of elements ... Of all your pictures, this is the one in which one feels the most perfect correlation between what you are aiming at and what appears on the screen ... To the eye, the ensemble is as perfect as an animated cartoon ..."[29]

Music[edit]

The music for Notorious is the least celebrated of the major Hitchcock scores, writes film scholar Jack Sullivan, one that few writers or fans talk about. "The neglect is unfortunate, for Roy Webb composed one of the most deftly designed scores of any Hitchcock film. It weaves a unique spell, one Hitchcock had not conjured before, and the hip, swingy source music is novel as well."[30]

The composer was Roy Webb, a staff composer at RKO, who had most recently scored the dark films of director Val Lewton for that studio. He wrote the fight song for Columbia University while he was there in the 1920s, then served as assistant to film composer Max Steiner until 1935; his reputation was "reliable, but unglamorous".[31] Hitchcock had tried to get Bernard Herrmann for Notorious, but Herrmann was unavailable; Webb too was a Herrmann fan: "Benny writes the best music in Hollywood, with the fewest notes", he said.[32]

Before the sale of the property to RKO, Selznick attempted, with typical Selznick gusto, to steer the course of the music.[33] He was miffed that no hit pop song had come out of his previous Hitchcock picture Spellbound, so he considered eighteen "gooey, sentimental songs"[33] like "Love Nest", "Don't Give Any More Beer to My Father" and "In A Little Love Nest Way Up on a Hill" for inclusion in Notorious. However, the sale removed Selznick as the decision-maker.[33]

Hitchcock was glad to be out from under Selznick's thumb. There would be "no sudsy violins in big love scenes, no more recycling of Selznick's favorite cues from past movies. He made sure there were no south-of-the-border cliches."[33] Selznick's exit also brought Hitchcock and Webb together into their natural sympatico. "Selznick deplored 'Hitchcock's goddamned jigsaw cutting', the dreamlike, jagged images that create his signature subjectivity. But Webb didn't mind jigsaw cutting at all. It complemented his fragmented musical architecture, just as the blocked passions of the film's characters reflect his unresolved harmonies. Like Hitchcock, Webb favored atmosphere and tonal nuance over broad gestures. Both men were classicists dealing in darkness and chaos."[32] They featured complementary personalities, too: "Webb had a modest ego, a handy trait when working for a control addict like Hitchcock."[34] Notorious was, however, their only film together.

Alicia and Devlin fall quickly in love once they arrive in Rio, and Webb uses tambourines, guitars, drums and Brazilian trumpets swinging into Brazilian dance music to provide "sensuous foreplay for the tumultuous love affair".[35] Numbers include "Carnaval no Rio", "Meu Barco", "Guanabara" and two sambas "Ya Ya Me Leva" and "Bright Samba". Yet understatement and atypical use are everywhere:

Sexy and full of danger, [the love music] is a typical Hitchcock romantic theme, though it is rarely used romantically. Even when Alicia and Devlin ascend a hill with a spectacular view and embrace during the initial courtship scenes—surely the cue for a fortissimo eruption of love music à la Spellbound—the theme sounds only for a teasing instant. For the most part, it appears at unpredictable times, in increasingly troubled harmonies, to capture the couple's shifting sexual subcurrents: Alicia's hurt and suppressed longing, Devlin's fear, jealousy, and hesitation.[36]

Often, Webb and Hitchcock use no music at all to undergird a romantic scene. The two-and-a-half minute kiss begins with distant music when it commences out on the balcony, but goes silent when the couple move inside.[37] Other times, they flout conventional wisdom: when Alicia asks the band to stop playing stuffy waltzes and liven things up with Brazilian music to cover her trip to the wine cellar with Devlin, Latin dance tunes replace the expected suspense cue.[37]

Aspects of Hitchcockian humor are present: When Alicia first enters the Sebastian mansion, loaded with sinister Nazis, Schumann is playing. "Wicked they may be, but these terrorists have artistic sensibilities and impeccable taste."[35]

Cinematography[edit]

Roger Ebert described Notorious as having "some of the most effective camera shots in his—or anyone's—work".[38] Hitchcock played off Grant's star power in his first scene, introducing his character with shots of the back of the actor's head showing him observing Alicia carefully. The excess of her drinking is reinforced the next morning with a close-up and zoom out from a glass of fizzing aspirin[39][40] beside her bed. The camera switches to her point of view and the viewer sees Grant as Devlin, backlit and upside down.[38] The film also contains a tracking shot at Sebastian's mansion in Rio de Janeiro: starting high above the entrance hall, the camera tracks all the way down to Alicia's hand, showing her nervously twisting the key there.[41][38]

Production credits[edit]

The production credits on the film were as follows:

- Director - Alfred Hitchcock

- Screenplay - Ben Hecht

- Director of photography - Ted Tetzlaff

- Art direction - Albert S. D'Agostino and Carroll Clark (art directors); Darrell Silvera and Claude E. Carpenter (set decorations)

- Special effects - Vernon L. Walker and Paul Eagler

- Music - Roy Webb (music), Constantin Bakaleinikoff (musical director), Gil Grau (orchestral arrangements)

- Editor - Theron Warth

- Sound - John E. Tribby and Terry Kellum

- Costumes - Edith Head (design of Ingrid Bergman's gowns)

- Assistant director - William Dorfman

- Production assistant - Barbara Keon

Themes and motifs[edit]

The predominant theme in Notorious is trust—trust withheld, or given too freely.[42] T. R. Devlin is a long time finding his trust, while Alexander Sebastian offers his up easily—and ultimately pays a big price for it. Likewise, the film addresses a woman's need to be trusted, and a man's need to open himself to love.[42]

Hitchcock the raconteur positioned it in terms of classic conflict. He told Truffaut that

[t]he story of Notorious is the old conflict between love and duty. Cary Grant's job—and it's rather an ironic situation—is to push Ingrid Bergman into Claude Rains's bed. One can hardly blame him for seeming bitter throughout the story, whereas Claude Rains is a rather appealing figure, both because his confidence is being betrayed and because his love for Ingrid Bergman is probably deeper than Cary Grant's. All of these elements of psychological drama have been woven into the spy story.[43]

Sullivan writes that Devlin sets up Alicia as sexual bait, refuses to take any responsibility for his role, then feels devastated when she does a superb job.[37] Alicia finds herself coldly manipulated by the man she loves, sees her notorious behavior exploited for political purposes, then fears abandonment by the lover who put her in the excruciating predicament of spying on her late father's Nazi colleague by sleeping with him—a man who genuinely loves her, perhaps more than Devlin does. Alex is Hitchcock's most painfully sympathetic villain, driven by his profound jealousy and rage—not to mention his enthrallment to an emasculating mother—culminating in an abrupt, absolute imperative to kill the love of his life.[37]

Hitchcock's own mother had died in September 1942, and Notorious is the first time he addresses his mother issues head-on. "In Notorious, the role of mother is at last fully introduced and examined. No longer relegated to mere conversation, she appears here as a major character in a Hitchcock picture, and all at once—as later, through Psycho, The Birds and Marnie—Hitchcock began to make the mother figure a personal repository of his anger, guilt, resentment, and a sad yearning."[44] At the same time, he blurred mother-love with erotic love,[45] and poignantly, in both the film and in its director's life, "both kinds of love were in fact limited to longing and fantasy and unfulfilled expectations".[45]

The theme of drinking weaves its way through the film from beginning to end: for Alicia it is an escape from guilt and pain, or even downright poisonous.[42] When a guest at the opening party tells her she has had enough, she scoffs: "The important drinking hasn't started yet." She camouflages emotional rejection with whiskey, at the opening party, the outdoor cafe in Rio, the apartment in Rio,[46] then drinking becomes even more dangerous as the Sebastians administer their poison through Alicia's coffee. Even the MacGuffin comes packaged in a wine bottle. "All the drinking is valueless and finally dangerous."[46]

Coming as it did on the heels of World War II, the theme of patriotism—and the limits thereof—makes it "astonishing that the movie was produced at all (and that it was such an immediate success), since it contains such blunt dialogue about government-sponsored prostitution: The sexual blackmail is the idea of American intelligence agents, who are blithely willing to exploit a woman (and even to let her die) to serve their own ends. The depiction of the moral murkiness of American officials was unprecedented in Hollywood—especially in 1945, when the Allied victory ushered in an era of understandable, but ultimately dangerous, chauvinism in American life."[27]

Notorious is notable among Hitchcock's films in that even though it is a spy thriller involving assassinations and attempts at assassination, no physical violence at all is shown on screen, except for the serving of poisoned coffee, and occasional gentle slaps.[47]

Reception[edit]

The film was the official selection of the 1946 Cannes Film Festival.[48] Notorious had its premiere at Radio City Music Hall in New York City on August 15, 1946, with Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant in attendance.

Box office[edit]

The film made $4.85 million in theatrical rentals in the United States and Canada on its first release, making it one of the highest-grossing films of the year.[49][50][51] Overseas, it earned $2.3 million, for worldwide rentals of $7.15 million, generating RKO a profit of $1.01 million.[52][49]

Reviews[edit]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 96% of 51 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Sublime direction from Hitchcock, and terrific central performances from Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant make this a bona-fide classic worthy of a re-visit."[53] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 100 out of 100, based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[54] As of April 2024, Notorious is one of 14 films with a score of 100 (perfect) on the website (two other Hitchcock films, Vertigo and Rear Window, are also on the list).[55]

Writing in The New York Times, Bosley Crowther praised the film, writing, "Mr. Hecht has written, and Mr. Hitchcock has directed in brilliant style, a romantic melodrama which is just about as thrilling as they come—velvet smooth in dramatic action, sharp and sure in its characters, and heavily charged with the intensity of warm emotional appeal."[56] Leslie Halliwell, usually terse, almost glowed about Notorious: "Superb romantic suspenser containing some of Hitchcock's best work."[57] Decades later, Roger Ebert also praised the film, adding it to his "Great Movies" list and calling it "the most elegant expression of the master's visual style".[38] Notorious was Patricia Hitchcock O'Connell's favorite of her father's pictures. "What a perfect film!", she told her father's biographer, Charlotte Chandler. "The more I see Notorious, the more I like it."[58]

Claude Rains was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and Ben Hecht was nominated for an Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay.

Legacy[edit]

Film critic Roger Ebert included Notorious in his Ten Greatest Films of All Time list in 1991, citing it as his favorite of Hitchcock's films.[59] Entertainment Weekly voted it at No. 66 on their list of The Greatest Films of All Time in 1999.[60] The Village Voice ranked Notorious at No. 77 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[61] In 2005, Hecht's screenplay was voted by the Writers Guild of America as one of the 101 best ever written.[62] The following year, Notorious was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". American Film Institute included the film as No. 38 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills and as No. 86 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions. Time magazine listed it among the All-TIME 100 films (a list of the greatest films since the magazine's inception) as chosen by Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel.[63] The film was voted at No. 38 on the list of "100 Greatest Films" by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008.[64] Notorious was ranked 68th in BBC's 2015 list of the 100 greatest American films.[65] In 2022, Time Out magazine ranked the film at No. 34 on their list of "The 100 best thriller films of all time".[66]

Adaptations[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

- The silent film Convoy (1927), co-produced by Victor Halperin, was based on the same Saturday Evening Post story.[67]

- A Lux Radio Theater adaptation was broadcast on January 26, 1948, with Ingrid Bergman reprising her role as Alicia Huberman and Joseph Cotten taking Cary Grant's role of T. R. Devlin. Another radio adaptation was produced for The Screen Guild Theater, again starring Ingrid Bergman, although this time with John Hodiak, and was broadcast on January 6, 1949.

- The film was remade in 1992 as the TV film Notorious directed by Colin Bucksey, with John Shea as Devlin, Jenny Robertson as Alicia Velorus, Jean-Pierre Cassel as Sebastian, and Marisa Berenson as Katarina.

- In the animated television series Star Wars: The Clone Wars the season two episode "Senate Spy" is a "compressed" adaptation of Notorious, even going so far as to frame the final shot of the episode the same way as the movie.[68]

- Mission: Impossible 2 paid strong homage to Notorious, but the plot is about a deadly virus instead of uranium, with the core story, many of the scenes, and some of the dialogue from Notorious being used.[69]

- The operatic adaption Notorious by Hans Gefors was premiered in Gothenburg in September 2015, starring Nina Stemme as Alicia Huberman.[70]

Tribute to Hitchcock[edit]

On March 7, 1979, the American Film Institute honored Hitchcock with its Life Achievement Award. At the tribute dinner, Ingrid Bergman presented him with the original ÚNICA key to the wine cellar - the single most notable prop in Notorious. After filming had ended, Cary Grant had kept it. A few years later he gave the key to Bergman, saying that it had given him luck and hoped it would do the same for her. When presenting it to Hitchcock, to his surprise and delight, she expressed the hope that it would be lucky for him as well.[71][72]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Notorious: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Variety (February 19, 2018). "Variety (September 1945)". New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Box Office Information for Notorious. The Numbers. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (1983). The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-345-31462-X. p. 304. Page numbers cited in this article are from the Ballantine Books first paperback edition, 1984

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (2004). Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-098827-2. p. 376

- ^ Leff, Leonard J. (1999). Hitchcock and Selznick: The Rich and Strange Collaboration of Alfred Hitchcock and David O. Selznick. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21781-0. p. 207

- ^ a b c d e Leff, p. 207

- ^ a b c McGilligan, p. 374

- ^ a b c Leff, p. 206

- ^ a b c d e f Spoto, Dark, p. 302

- ^ Leff, p. 209

- ^ Spoto, Dark, p. 297

- ^ a b c d Spoto, Dark, p. 298

- ^ Notorious was his tenth single word-titled film: Downhill, Champagne, Blackmail, Murder!, Sabotage, Suspicion, Saboteur, Lifeboat and Spellbound preceded it; Rope, Vertigo and Frenzy followed. His other one-worders, Rebecca, Psycho, Marnie and Topaz take their titles from the one-word titles of the novels they derive from. Spoto, Notorious, p. 195n

- ^ McGilligan, p. 366

- ^ Spoto, Donald, (2001). Notorious: The Life of Ingrid Bergman. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81030-5. p. 195

- ^ a b Spoto, Dark, p. 299

- ^ a b Spoto, Dark, p. 301

- ^ Truffaut, François (1967). Hitchcock By Truffaut. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-60429-5

- ^ McGilligan, p. 375

- ^ a b Leff, p. 208

- ^ a b c McGilligan, p. 379

- ^ Spoto, Dark, p. 303

- ^ a b c d e McGilligan, p. 380

- ^ McGilligan, p. 376

- ^ Spoto, Notorious, p. 198

- ^ a b c Spoto, Notorious, p. 197

- ^ Spoto, Notorious, pp. 197–198

- ^ Truffaut, p. 173

- ^ Sullivan, Jack (2006). Hitchcock's Music. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13618-0. p. 124

- ^ Sullivan, p. 124

- ^ a b Sullivan, p. 125

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, p. 126

- ^ Sullivan, p. 130

- ^ a b Sullivan, p. 127

- ^ Sullivan, p. 131

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, p. 132

- ^ a b c d Ebert, R.Great Movies:Notorious, August 17, 1997. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 6 September.

- ^ Alka-Seltzer

- ^ Bromo-Seltzer

- ^ Duncan, Paul, (2003). Alfred Hitchcock: Architect of Anxiety 1899–1980. Los Angeles: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-1591-8. p. 110

- ^ a b c Spoto, Notorious, p. 196

- ^ Truffaut, p. 171

- ^ Spoto, Dark, p. 306

- ^ a b Spoto, Dark, p. 307

- ^ a b Spoto, Dark, p. 308

- ^ French, Philip (January 18, 2009). "Notorious". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Notorious". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^ a b "Richard B. Jewell's RKO film grosses, 1929–51: The C. J. Trevlin Ledger: A comment". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Volume 14, Issue 1, 1994.

- ^ "All-Time Top Grossers". Variety. January 8, 1964. p. 69.

- ^ "60 Top Grossers of 1946". Variety. January 8, 1947. p. 8 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Jewell, Richard; Harbin, Vernon (1982). The RKO Story. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House. p. 212.

- ^ "Notorious". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ "Notorious". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ "Best Movies of All-Timr". Metacritic. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. "The Screen in Review." The New York Times, August 16, 1946

- ^ Walker, John, ed. Halliwell's Film Guide. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-273241-2. p. 873

- ^ Chandler, p. 163

- ^ "Ten Greatest Films of All Time". Roger Ebert. April 1, 1991.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (February 12, 2005). "Notorious (1946) – ALL-TIME 100 Movies". Time. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "Cahiers du cinéma's 100 Greatest Films". November 23, 2008.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest American Films". bbc. July 20, 2015.

- ^ "The 100 best thriller films of all time". Time Out. March 23, 2022.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (March 25, 2023). "A Brief History of Hitchcock Remakes". Filmink.

- ^ Young, Bryan (October 23, 2012). "The Cinema Behind Star Wars : Notorious". StarWars. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "Did You Know 'Mission: Impossible 2' is a Remake of Hitchcock's 'Notorious'? Here, Have a Look..." ComingSoon.net. February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Notorious". Göteborgsoperan. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ McGilligan, p. 471

- ^ "Hitch & Ingrid". YouTube.

Sources[edit]

- Brown, Curtis F. The Pictorial History of Film Stars – Ingrid Bergman. New York: Galahad Books, 1973. ISBN 0-88365-164-5, p. 76–81

- Eliot, Marc (2005). Cary Grant. London: Aurum Press. pp. 434 pages. ISBN 1-84513-073-1.

- Humphries, Patrick. The Films of Alfred Hitchcock. Crescent Books, a Random House company, 1994 revised edition. ISBN 0-517-10292-7, p. 88–93

- McGilligan, Patrick (2003). Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. London: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 850 pages. ISBN 0-470-86973-9.

- Park, William (2011), "Appendix A:Within the Genre", What is Film Noir?, Bucknell University Press, ISBN 978-1-6114-8363-5

- Spoto, Donald (2001). Notorious: The Life of Ingrid Bergman. America: DaCapo Press. pp. 474 pages. ISBN 0-306-81030-1.

External links[edit]

- Notorious at IMDb

- Notorious at the TCM Movie Database

- Notorious at AllMovie

- Notorious at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Notorious an essay by William Rothman at the Criterion Collection

- Reprints of historic reviews, photo gallery at CaryGrant.net

Streaming audio

- Notorious radio adaptation on MP3 aired January 26, 1948 on Lux Radio Theatre (59 minutes, with Ingrid Bergman and Joseph Cotten)

- Notorious on Screen Guild Theater: January 6, 1949

- 1946 films

- 1940s romantic thriller films

- 1940s political thriller films

- 1940s spy thriller films

- American black-and-white films

- American romantic thriller films

- American spy thriller films

- 1940s English-language films

- Film noir

- Films scored by Roy Webb

- Films directed by Alfred Hitchcock

- Films produced by Alfred Hitchcock

- Films set in Rio de Janeiro (city)

- American political thriller films

- RKO Pictures films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films adapted into operas

- Films set in 1946

- Films set in country houses

- Films with screenplays by Ben Hecht

- 1940s American films