María del Pilar Sinués

María del Pilar Sinués de Marco | |

|---|---|

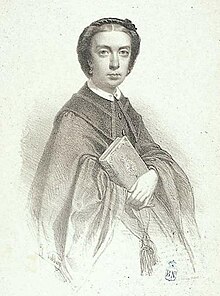

María del Pilar Sinués de Marco, lithograph by José Vallejo y Galeazo. Illustration in her work, La ley de Dios. Colección de leyendas, Madrid, 1858. Biblioteca Nacional de España. | |

| Born | María del Pilar Sinués y Navarro December 19, 1835, Zaragoza, Aragon, Spain |

| Died | November 20, 1893 Madrid, Spain |

| Pen name | Laura |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | Convent of Santa Rosa (Zaragoza) |

| Genre |

|

| Notable works | El ángel del hogar |

| Spouse |

José Marco y Sanchís

(m. 1856; separation 1875) |

| Signature | |

María del Pilar Sinués y Navarro de Marco (December 19, 1835, Zaragoza, Aragon - November 20, 1893, Madrid), was a popular and prolific 19th-century Spanish writer of various genres including novels, poetry, and informative works. She used the pen name Laura for her journalistic articles in the magazine she directed. Sinues lived entirely off of her literary production.[1] Her 1857 conduct book, El ángel del hogar (The angel of the house), was reprinted for at least thirty years, the last edition being published in 1881.[2] She was the founder and editor-in-chief of two popular women's magazines, El Angel del Hogar[3] (1864-1869) and Flores y Perlas (1883-1884).[4]

Early life and education[edit]

María del Pilar Sinués y Navarro was born on December 19, 1835, in Zaragoza, Aragon, Spain.[5] She was the daughter of Pedro Sinués y Yoldi and Flora Navarro. She received her education at the convent of Santa Rosa,[5] thanks to which she developed literary qualities.

Career[edit]

She published her first novel, Rosa, in 1851.[6] Between 1853 and 1854, Sinues published eleven poems in the newspaper El Avisador and five in El Esparterista. The poems are of religious, family, and political themes; an example of the latter is that she dedicated a poem to the "undefeated Duke of la Victoria" in addition to other poems.[7] Sinues published her first collection of poems Mis vigilias in 1854.[8]

Madrid[edit]

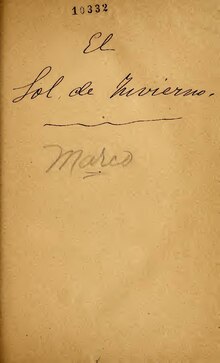

In 1856, she married by proxy the Valencian journalist and comedian José Marco y Sanchís (1830-1895),[9] whom she only knew from letters due to their mutual admiration for her works. The marriage proposal arose from a meeting of bohemian poets among whom was Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, who after reading one of Sinues' poems and in the face of general enthusiasm, provoked in Marco y Sanchís the desire to marry Sinues.[7] Afterward, the couple moved to live in Madrid and she wrote under the name "María del Pilar Sinués de Marco". In Madrid, the couple collaborated in several publications such as the magazine La España musical y Literaria. Her husband also adapted Sinues' work, El sol de invierno (The Winter Sun), to the theater with notable success.

The magazine Álbum de senoritas, with which Bécquer had a strong connection, published one of Sinues' fables. She thus fully entered the literary life of the Court. She became a frequent character in publications, both as an author and as a protagonist of cultural life.[7] The newspaper La Época forwarded the gift of a bracelet from the Countess of San Antonio in gratitude for the Sinues' work.[10] Present in literary forums and gatherings, she acquired great renown and was rewarded with tributes and awards.

Sinues directed her weekly magazine El ángel del hogar (The angel of the home) between 1864 and 1869, a publication on literature, theater, fashion, and work. From this magazine, she supported the Glorious Revolution of 1868 and dedicated articles on the initiatives of female instruction advocated by the Complutense University of Madrid in 1869.[11]

She collaborated in multiple magazines such as La Educación Pintoresca, El Fénix, La Educanda, and El Periódico Ilustrado. She also translated works from French.[10]

She published 66 novels as narrative works, including legends and stories, and collaborated in 38 magazines and newspapers.[10] This caused her to be criticized for her prolixity; in the satirical magazine El Moro Muza, a parody of her was made about an anecdote that she would collect and about which she would put together a novel. She was also criticized for her progressive ideas.[10]

Making a living from the sale of her books exposed her contradiction as, according to Julio Nombela, Sinues did not live as she taught women. She enjoyed economic independence as well as a very intense intellectual and active life. However, when Mariano de Cavia ridiculed the founder of the Ateneo de Señoras, Faustina Sáez de Melgar, in a column, Sinues completely distanced himself from Sáez. Sinues also criticized Rosario de Acuña for her prominence in intellectual life and her political stance.[10]

Sinues participated in the women's branch of the Sociedad Abolicionista Española along with Faustina Sáez de Melgar, Ángela Grassi, Micaela de Silva y Collás, and Blanca de Gassó y Ortiz among others.[12] She was appointed secretary but resigned immediately, perhaps to avoid spoiling her public image.[10]

In 1875, Sinues separated from her husband and left for Paris as a correspondent.[9] This brought her institutional ostracism as she broke the domestic rhetoric demanded of virtuous women writers.[11] She was aware of her personal evolution, which was accentuated by her marital separation. In 1879, she defended literary professionalization.[11]

She published regularly in the progressive newspaper El impartial with topics related to the female question such as education, the possibility of working, morality, and religion.6[13] In 1883, she launched the first issue of Flores y Perlas, directed by her and written only by women, but nothing further is recorded about the continuity of the magazine.[10]

The discredit into which the figure of Sinués fell was due to the devaluation of Elizabethan culture by considering Sinues feminine and far from the male creative genius, the dominant concept in the Restoration.[11]

Death and legacy[edit]

María del Pilar Sinués de Marco died on November 20, 1893, in Madrid.[9][14] Two of Sinues' works were declared official texts in all schools: La ley de Dios: Leyendas (The Law of God: Legends) (1858) and A la luz de la lámpara: Cuentos morales (By the Light of the Lamp: Moral Tales) (1862). In Zaragoza, there is a street named after her. The University of Zaragoza has a room named after him.

Themes[edit]

Her works contained educational and moralizing themes, often exemplifying the ideal of women's behavior as mothers and wives. Her texts include a pedagogy full of romanticism. She intended to teach by delighting the reader.[1] Her situation as a writer and pedagogue led to an indoctrination that was not reflected in the female characters of her works, which led to a conflict in her educational task.[13] In her works, she designed the model of the woman of her time: good daughters, with a suitable husband; mothers, responsible for the education of their children, and with an eye to the general happiness of their family. All this was presented from a Catholic and conservative point of view.

Sinués obtained her great literary success because she adhered to the "Elizabethan canon" that associated aesthetic beauty with works of Christian inspiration and moralizing. The undisputed influence came from the theoretical works of the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine on Christian idealism that endorsed women's literature of sentimental, religious, domestic, and landscape themes, where Sinués came in. The first works of Sinués are medieval legends, with a clear romantic influence. Later, she wrote costumbrist works in the style of Böhl de Faber, and in the moralist and educational El ángel del hogar, Sinues will enumerate how a virtuous writer who is also a daughter, sister, mother, and wife should be; her private life must be blameless.[11]

When she moved to Madrid, she expanded her literary work by writing manuals of conduct for the Christian family, bulletins, and translations of French novels. Little by little, she moved away from Elizabethan precepts and entered into the realist aesthetic that was being imposed in the French novel. An example would be Fausta Sorel in 1861. Also between 1864 and 1869, she wrote a nine-volume Galería de mujeres célebres (Gallery of Famous Women), which includes female trajectories far from "the angel of the home".[11]

Selected works[edit]

Novels[edit]

- Rosa, 1851.

- La diadema de perlas, 1857.

- Margarita, 1857.

- Premio y castigo, 1857. (Dedicated to Carolina Coronado.)

- Un nido de palomas, 1861.

- Fausta Sorel, 1861.

- A la sombra de un tilo, 1862.

- El lazo de flores, 1862. (Novel.)

- El sol de invierno, 1863. (The novel was adapted for the stage by her husband.)

- Celeste, 1863.

- La senda de la gloria, 1863.

- La Virgen de las lilas, 1865.

- El almohadón de rosas, 1864.

- No hay culpa sin pena, 1864.

- El alma enferma, 1864.

- Querer es poder, 1865.

- A río revuelto, 1866.

- La familia cristiana. La corona nupcial, 1871.

- Volver bien por mal, 1872.

- Las alas de Ícaro, 1872.

- El último amor, 1872.

- Una hija del siglo, 1873.

- El becerro de oro, 1875.

Folklore[edit]

- Luz de Luna, 1855. (Historical legend set in the 15th century)

- Cantos de mi lira, 1857. (Legends in verse. In the current of Romanticism.)

- Amor y llanto, 1857. (Historical legends.)

- La Ley de Dios, 1858. (Collection of legends based on the Ten Commandments. One of her most acclaimed works.)

- ¡¡Pobre Ana !!, 1861. (Historical legend.)

- A la luz de una lámpara, 1862. (Compilation of moral tales.)

- Galería de mujeres célebres, 1868. (Biographical legends.)

- El cetro de flores, 1865. (Collection of historical legends.)

- Cuentos de color de cielo, 1867. (Collection of stories and tales.)

Other[edit]

- Mis vigilias, 1854. (Poems, verse narratives, short stories and essays.)

- El ángel del hogar, 1859.

- Flores del alma, 1860. (Poems.)

- La rama de sándalo, 1862.

- Sueños y realidades, 1862.

- Hija, esposa y madre, 1866. (Pedagogical letters.)

- Veladas de invierno, en torno a una mesa de labor, 1866.

- El camino de la dicha, 1866. (Letters to two brothers on education.)

- Un libro para las damas, 1875. (Studies on female education. Reference work on the educational system.)

- La vida íntima, 1876. (Epistles.)

- Combates de la vida, 1876. (Social pictures.)

- Plácida, 1877. (Family drama.)

- Un libro para las madres, 1877.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sáenz Pérez, Rebeca. "El ángel del hogar, de María Pilar Sinués, modelo de mujer en el s.XIX" (PDF). biblioteca.unirioja.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Molina Puertos, Isabel. “La doble cara del discurso doméstico en la España liberal: El Ángel del hogar de Pilar Sinués”. Pasado y Memoria. N. 8 (2009). ISSN 1579-3311, pp. 181-197

- ^ Sieburth, Stephanie (1994). Inventing High and Low: Literature, Mass Culture, and Uneven Modernity in Spain. Duke University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8223-1441-7. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ LaGreca, Nancy (1 January 2009). Rewriting Womanhood: Feminism, Subjectivity, and the Angel of the House in the Latin American Novel, 1887-1903. Penn State Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-271-04685-3. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b Llama, Iñigo Sánchez (2001). Antología de la prensa períodica isabelina escrita por mujeres, 1843-1894 (in Spanish). Universidad de Cádiz, Servicio de Publicaciones. p. 175. ISBN 978-84-7786-749-4. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Llama, Iñigo Sánchez (2000). Galería de escritoras isabelinas: la prensa periódica entre 1833 y 1895 (in Spanish). Universitat de València. ISBN 978-84-376-1866-1. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Romero Tobar, Leonardo (30 June 2014). "María Pilar Sinués, de la provincia a la capital del reino". Arbor (in Spanish). 190 (767). ISSN 1988-303X. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Mis vigilias". datos.bne.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "El Ángel del hogar (Madrid)". Hemeroteca Digital. Biblioteca Nacional de España (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Molina Puertos, Isabel (2015). La ficción doméstica: Ángela Grassi, Pilar Sinués y Faustina Sáez. Una aproximación a las imágenes de género en la España burguesa (Thesis) (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Sánchez-Llama, Íñigo (1999). "María del Pilar Sinués de Marco y la cultura oficial peninsular del siglo XIX: del neocatolicismo a la estética realista". Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos (in Spanish). 23 (2): 271–288. ISSN 0384-8167. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Consejería de Empleo, Turismo y Cultura. Dirección General de Bellas Artes. "Biblioteca Digital de la Comunidad de Madrid". bibliotecavirtualmadrid.comunidad.madrid (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b Sanz, Alba González (21 November 2013). "Domesticar la escritura. Profesionalización y moral burguesa en la obra pedagógica de María del Pilar Sinués (1835-1893)". Revista de Escritoras Ibéricas (in Spanish). 1: 51–99. doi:10.5944/rei.vol.1.2013.5353. hdl:10651/31429. ISSN 2340-9029. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Sinués, María del Pilar". www.bne.es (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de España. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Bibliography[edit]

- Hormigón, Juan Antonio (1996). Autoras en la Historia del Teatro Español (1500-1994). Madrid: Publicaciones de la Asociación de Directores de Escena de España. ISBN 8487591590.

- Ruiz Lasala, Inocencio; Ruiz Lasala, Inocencio (1977). Bibliografía zaragozana del XIX d. C. Zaragoza: Ayuntamiento. ISBN 84-505-5440-3.

- Simón Palmer, Carmen (1991). Escritoras españolas del siglio XIX. Manual biobibliográfico. Madrid: Castalia. ISBN 8437613167.

- Urrutia, Jorge, ed. (1995). Poesía española del siglio XIX. Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 8437613167.

- Navales, Ana María (1999). "María del Pilar Sinués, escritora zaragozana del siglio XIX". Heraldo de Aragón.

- 1835 births

- 1893 deaths

- Spanish women writers

- 19th-century Spanish novelists

- Spanish women novelists

- 19th-century Spanish poets

- Spanish women poets

- 19th-century Spanish journalists

- Spanish women journalists

- Spanish feminist writers

- Spanish folklorists

- Spanish magazine editors

- Women magazine editors

- Spanish women folklorists

- Spanish magazine founders

- Women founders

- 19th-century pseudonymous writers

- Pseudonymous women writers