Lonnie Frisbee

Lonnie Frisbee | |

|---|---|

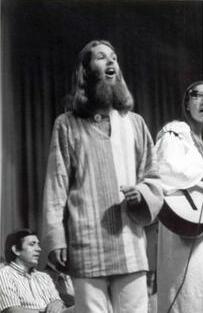

Frisbee in the 1960s | |

| Born | Lonnie Ray Frisbee June 6, 1949 Costa Mesa, California, U.S. |

| Died | March 12, 1993 (aged 43) |

| Occupation(s) | Charismatic evangelist and minister |

| Years active | 1966–1991 |

| Spouse | Connie Bremer (div. 1973) |

Lonnie Ray Frisbee (June 6, 1949 – March 12, 1993) was an American Charismatic evangelist in the late 1960s and in the 1970s; he was a self-described "seeing prophet".[1][2] He had a hippie appearance.[3][4] He was notable as a minister and evangelist in the Jesus movement.[5][6]

Eyewitness accounts of his ministry, documented in the 2007 documentary, Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher portray Frisbee; he became a charismatic spark igniting the rise of Chuck Smith's Calvary Chapel and the Vineyard Movement. They are two worldwide denominations and among the largest evangelical denominations beginning at that time.[5][7] Reportedly, "he was not one of the hippie preachers, but rather that "there was one—Frisbee".[8][9] His brand of ministry was named power evangelism'. Later he was harshly criticized for his great focus and concentrating heavily on the Holy Spirit and the gifts of the Spirit, often by individuals in the same churches which he co-founded.[10]

Frisbee influenced prophetic evangelists including Jonathan Land, Marc Dupont, Jill Austin and several others.[10] Frisbee co-founded the House of Miracles commune and found many converts. The House of Miracles grew into nineteen communal houses; they later moved to Oregon to form Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, the largest and one of the longest-lasting Jesus People communal groups.

Frisbee had an evangelical ministry while privately socializing as a homosexual man, before and during his evangelism career, although in interviews he said that he never believed homosexuality was anything other than sin in the eyes of God.[5] Both denominations he helped found prohibited homosexual behavior, and he was later excommunicated by the denominations because of his active sexual life. They first removed him from leadership positions, and later fired him.[5] He is portrayed by Jonathan Roumie in the 2023 film Jesus Revolution, which highlights his ministry with Chuck Smith and the impact he had on Greg Laurie's evangelism.[5]

Early life and career[edit]

Frisbee was mostly raised in a single-parent home and was exposed to "sketchy, dangerous characters" as a child.[6][11] While researching his documentary, Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher, filmmaker David di Sabatino stated Frisbee's brother claimed Lonnie was raped at the age of eight. Also revealed in the film was that Frisbee ran away frequently and entered into Laguna Beach's homosexual underground scene with a friend when he was 15. Di Sabatino further commented that an incident such as the alleged rape, "fragments your identity", and that he saw Frisbee's homosexuality as a flaw.[4][6] During his childhood, Frisbee's father ended up leaving their home, and the boy, fatherless. His mother later tracked down and married the former husband of the woman Frisbee's father became involved with.[12]

Lonnie Frisbee showed intense interest in the arts and cooking.[12] He won awards for his paintings and even appeared as a featured dancer on Casey Kasem's mid-60s TV show Shebang.[12] He exhibited a "bohemian" streak and regularly ran away from home.[12] As a teen he became involved in the drug culture as part of his spiritual quest,[12] and at fifteen he entered Laguna Beach's homosexual underground scene with a friend.[6][11] His spotty high school education left him barely able to read and write.[11] At 18 he joined thousands of other flower children and hippies for the Summer of Love in San Francisco in 1967.[13] He described himself as a "nudist-vegetarian-hippie".[10]

Frisbee's unofficial evangelism career began as a part of a soul-searching LSD acid-trip as part of a regular "turn on, tune in, drop out" session of getting high.[6] He would often read the Bible while on a trip.[12] On a pilgrimage with friends to Tahquitz Canyon outside Palm Springs, instead of looking for meaning again in mysticism and the occult, Frisbee started reading the Gospel of John to the group, eventually leading the group to Tahquitz Falls and baptizing them.[6] A later acid-trip in the same area produced "a vision of a vast sea of people crying out to the Lord for salvation, with Frisbee in front preaching the gospel."[12] His "grand vision of spreading Christianity to the masses" alienated his family and friends.[12] Frisbee moved to San Francisco where he had won a fellowship to the San Francisco Art Academy.[12] He soon met members of Haight-Ashbury's Living Room mission. At the time he talked about UFOs, practiced hypnotism, and talked about dabbling in occultism and mysticism.[14] When Steve and Sandi Heefner and Ted and Connie Wise first met him, they said he was talking about "Jesus and flying saucers". Frisbee converted to Christianity and joined their first street Christian community, The Living Room, a storefront coffeehouse commune of four couples in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco started in 1967.[15][16] He quit the art academy and moved to Novato, California, where the Heefners and Wises set up a commune and later reconnected with his former girlfriend Connie Bremer, whom he then married. The community was soon dubbed The House of Acts after the community of early Christians in the Acts of the Apostles. Frisbee designed a sign to put outside the house, but was informed that if he gave it an official name, it would no longer be considered a mere guest house and would be subject to renovations. The community took the sign down to avoid the financial obligation. Frisbee continued painting detailed oils including several of missions.[11]

Jesus movement, Calvary Chapel[edit]

Chuck Smith had been making plans to build a chapel out of a surplus school building in the city of Santa Ana, near Costa Mesa, when he met Frisbee. Smith's daughter's boyfriend John Nicholson was a former addict who had turned to Christianity. When Smith said he wanted to meet a hippie, John brought home Frisbee (who was hitch-hiking), so he could meet people to talk about Jesus and salvation.[11] Frisbee and his wife Connie joined the fledgling Calvary Chapel congregation and Smith was struck by Frisbee's charisma. Smith said, "I was not at all prepared for the love that this young man would radiate."[15] Frisbee became one of the most important ministers in the church when on May 17, 1968, Smith put the young couple in charge of the Costa Mesa rehab house called "The House of Miracles" with John Higgins and his wife Jackie. Within a week it had 35 new converts. Bunk beds were built in the garage to house the new converts.[11] Frisbee led the Wednesday night Bible study, which soon became the central night for the church attracting thousands.[15] Frisbee's attachment to the charismatic Pentecostal style caused some disagreement within the church, since he seemed focused more on gaining converts and experiencing the presence of the Holy Spirit than on teaching newer converts Biblical doctrine.[5] Chuck Smith took over teaching and welcomed Frisbee into his church.[17] Frisbee's appearance helped appeal to hippies and those interested in youth culture, and he believed that the youth culture would play a prominent role in the Christian movement in the United States. He cited Joel the prophet and remained upbeat despite what the young couple saw as unbalanced treatment, as Frisbee was never paid for his work and another person was hired full-time as Smith's assistant.[9]

The country was being swept with a youth movement with California as an epicenter.[18] The counterculture of hippies and surfers hung around the beaches; music and dancing to the music was the main form of communication.[18] Frisbee walked on the beaches during the day to convert the young people; he brought them to church for the nightly services.[18]

The House of Miracles grew into a series of nineteen communal houses that later migrated to Oregon to form Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, the largest and one of the longest lasting of the Jesus People communal groups which had 100,000 members and 175 communal houses spread across North America.[19] This may have been the largest Christian communal group in U.S. history.[19]

From 1968 to 1971, Frisbee was a leader in the Jesus movement, bringing in thousands of new converts and influencing Calvary Chapel leaders including Mike MacIntosh and Greg Laurie, whom he mentored.[6][15]

Fame[edit]

"Jesus Freaks", or "Jesus People" as they were often called, were documented in media including the Kathryn Kuhlman I Believe In Miracles show; Frisbee was a featured guest on the show talking about Jesus, the prophets, and quoting scripture.[20] By 1971, the Jesus Movement was covered in the media with major media outlets like Life, Newsweek and Rolling Stone reporting on it. Frisbee, due to his prominence in the movement, was often photographed and interviewed. Also in 1971 Frisbee and Smith parted ways because their theological differences had become too great. Smith discounted Pentecostalism, maintaining that love was the greatest manifestation of the Holy Spirit, while Frisbee was strongly involved in theology which centered on spiritual gifts and New Testament experiences. Frisbee announced that he would leave California altogether and go to a movement in Florida led by Derek Prince and Bob Mumford which taught a pyramid shepherding style of leadership and was later referred to as the Shepherding Movement.[11]

In 1973, the Frisbees divorced because Frisbee's pastor had an affair with his wife. Frisbee mentioned that in a sermon he gave at the Vineyard Church in Denver a few years before he died.[2] Connie later remarried and Lonnie left the organization.

Vineyard movement[edit]

Meanwhile in May 1977, John Wimber laid the groundwork for what would become the Association of Vineyard Churches, also known as the Vineyard Movement. He witnessed the explosive growth of Calvary Chapel and wanted to build a church which embraced the healings and miracles that he had previously been taught were no longer a part of Christian life.[citation needed] He began teaching and preaching about spiritual gifts and healings, but Wimber held that it wasn't until May 1979, when Frisbee gave his testimony during an evening service at what was then the Yorba Linda branch of the Calvary Chapel movement (later the Anaheim Vineyard Christian Fellowship) that the charismatic gifts of the Holy Spirit took hold of the church.[21]

Since his early days at Calvary Chapel Costa Mesa, Frisbee shifted in his emphasis from evangelism to the dramatic and demonstrative manifestation of the power of the Holy Spirit. After speaking Frisbee invited all the young people 25 and under to come forward; he invited the Holy Spirit to bring God's power into their lives. Witnesses say it looked like a battlefield as young people fell and began to shake and speak in tongues.[22] The young kids, many in junior high and high school, were so "filled with the Spirit" that they soon started baptizing friends in hot tubs and swimming pools around town.

The church catapulted in growth over the next few months and the event is credited with launching the Vineyard Movement.[23] After that time Frisbee and Wimber began traveling the world, visiting South Africa and Europe. Frisbee was a much sought-after preacher with his "Jesus-like" look getting him instant recognition from South Africa to Denmark.[6][9] While there, they purportedly performed many healings and miracles for people.[10] As reported by many who were there, Frisbee was integral to the development of what would later become Wimber's "Signs and Wonders theology".

Sexuality revealed[edit]

Although Frisbee's homosexuality was documented as a "bit of an open secret in the church community" and that he would "party" on Saturday night then preach Sunday morning, many in the church were unaware of his "other life."[24] Eventually some church officials felt that Frisbee's inability to overcome sexual immorality became a hindrance to his ministry. An article in The Orange County Weekly, headlined "The First Jesus Freak," chronicles Frisbee's life in which Matt Coker writes, "Chuck Smith Jr. says he was having lunch with Wimber one day when he asked how the pastor reconciled working with a known homosexual like Frisbee. Wimber asked how the younger Smith knew this. Smith said he'd received a call from a pastor who'd just heard a young man confess to having been in a six-month relationship with Frisbee. Wimber called Smith the next day to say he'd confronted Frisbee, who openly admitted to the affair and agreed to leave."[6]

By his own account,[25] Frisbee was raped by a man who had attended one of Lonnie's revival meetings six years prior. Lonnie says "Over the next few weeks, this man began to spread it around that he had a sexual relationship with Lonnie Frisbee. He told people, including church leaders, that he had sex with me. Not true. I was violently forced at knifepoint totally against my will. His lies caused me years of not being able to minister, as this accusation spread throughout the Christian community." He describes next some of the fallout. "I gave in to drugs and sexual temptation. I had become deceived and overpowered. I had been constantly accused of things, mostly of which I didn't do---so why not live up to my reputation? That was more or less my subconscious justification for crossing the lines. I blamed everyone else, including the church."

However, Frisbee stated that he never characterized himself as a homosexual: "... in the last segment of my life story. I said it was a counterfeit. But I would like to go into the subject a little more at this time... I stated 'I never lived the gay lifestyle,' I would like to add that I have never even considered myself a homosexual at all, even though I had been molested for years as a child, had sexually experimented as a part of the rebellious 'free love generation'... and there is also my disappointing backsliding days in the mid-eighties."[26]

In 2005, film critic Peter Chattaway interviewed David Di Sabatino (director of the documentary Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher) for Christianity Today; they spoke about addressing Frisbee's homosexuality with his family. Di Sabatino said, "I brought to light some things that not a lot of people knew. I've been in rooms with his family where I've had to tell them that he defined himself as gay, way back. Nobody knew that. There's a lot of hubris in that, to come to people who loved him and prayed for him, and to stand there and say, 'You didn't really know this, but...'"[4] In the same interview Di Sabatino also said, "His early testimony at Calvary Chapel was that he had come out of the homosexual lifestyle, but he felt like a leper because a lot of people turned away from him after that, so he took it out of his testimony—and I think that's an indictment of the church."[4] Di Sabatino commented on Frisbee's homosexuality as a flaw.[4]

Death[edit]

At the time of his death in 1993, a brain tumor was named as the cause. A source claimed Frisbee contracted AIDS and died from complications associated with the condition;[11] At his funeral at the Crystal Cathedral, Calvary Chapel's Chuck Smith eulogized Frisbee as a spiritual son and said he was a Samson-like figure, saying that he was a man through whom God did many great works, but that he was the victim of his own struggles and temptations.[27] Some saw this as further maligning Frisbee's work and an inappropriate characterization at the service.[5] Others including Frisbee's friend John Ruttkay, saw the Samson analogy as being spot on, and said so at his funeral.[5] Frisbee was interred in the Crystal Cathedral Memorial Gardens.[28]

In popular culture[edit]

Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher[edit]

David Di Sabatino produced and directed the video documentary: Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher. Narrated by Jim Palosaari, it received an Emmy Award nomination from the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (San Francisco/NorCal chapter).

Finished in March 2005, Frisbee was first accepted to the Newport Beach Film Festival where a showing at the Lido Theater was sold out. The theater is not far from the Blue Top commune, a Christian community of young hippie believers which was run by the Frisbees in the late 1960s. The documentary was also accepted to the Mill Valley (2005), Reel Heart (2005), Ragamuffin (2005), San Francisco International Independent (2006), New York Underground (2006), and Philadelphia Gay & Lesbian (2006) film festivals. The edited version of the movie was shown on San Francisco's KQED in November 2006; the film was released on DVD in January 2007.

A soundtrack featuring the music of The All Saved Freak Band, Agape, Joy, and Gentle Faith was released in May 2007.[29] A pre-release version of the DVD was produced that featured 21 recordings of songs by Larry Norman as a solo artist,[30] other songs by Randy Stonehill, Love Song, Fred Caban, Mark Heard, and Stonewood Cross are included. However, due to licensing issues most of the music was changed for the final release.[31][better source needed]

Jesus Revolution[edit]

The 2023 movie Jesus Revolution starred Jonathan Roumie as Lonnie Frisbee, and Kelsey Grammer as Pastor Chuck Smith. The movie's theme is the rise of the Jesus Movement and features Frisbee as one of the film's main characters.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Frisbee, Lonnie. "Lonnie Frisbee ministering at Vineyard Church in Denver, CO; Senior Pastor Tom Stipe". Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Jansson, Erik. "Lonnie Frisbee ministering at Vineyard Church in Denver, CO". Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ^ Annette Cloutier, Præy To God: A Tasteful Trip Through Faith: Volume One, ISBN 1-4363-1555-7, ISBN 978-1-4363-1555-5, p. 437.

- ^ a b c d e Chattaway, Peter. "Documentary of a Hippie Preacher". Archived from the original on May 11, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h David di Sabatino (2001). Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher (Documentary movie). United States: David Di Sabatino.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coker, Matt. "The First Jesus Freak" Archived August 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. OC Weekly, March 3, 2005. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ Glen G. Scorgie, A Little Guide to Christian Spirituality: Three Dimensions of Life with God, Chapter 8-"An Integrated Spirituality", Zondervan, 2009, ISBN 0-310-54000-3, ISBN 978-0-310-54000-7.

- ^ Barkonsty. "teaser for the documentary FRISBEE: The Life & Death of a Hippie Preacher". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ a b c Coker, Matt (April 14, 2005). "Ears on Their Heads, But They Don't Hear: Spreading the real message of Frisbee". Orange County Weekly. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- ^ a b c d John Crowder, Miracle workers, reformers and the new mystics, Destiny Image Publishers, 2006, ISBN 0-7684-2350-3, ISBN 978-0-7684-2350-1, pp. 103–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greg Laurie, Ellen Vaughn, Lost Boy: My Story , Gospel Light, 2008, ISBN 0-8307-4578-5, ISBN 978-0-8307-4578-4, pp. 81–3, 85–9, 106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i David W. Stowe, No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism, UNC Press Books, 2011, ISBN 0-8078-3458-0, ISBN 978-0-8078-3458-9, pp. 23–9.

- ^ Don Lattin, Jesus Freaks: A True Story of Murder and Madness on the Evangelical Edge, HarperCollins, 2008, ISBN 0-06-111806-0, ISBN 978-0-06-111806-7, pp. 31–3.

- ^ Bill (Wam957). "The Son Worshipers, 30-minute documentary on the Jesus Movement circa 1971. Edited by Bob Cording and Weldon Hardenbrook". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Balmer, Randall (January 2002). The Encyclopedia of Evangelism, page 227, 303, 532. ISBN 9780664224097. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ Stephen J. Nichols. Jesus Made in America: A Cultural History from the Puritans to the Passion of the Christ, InterVarsity Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8308-2849-4, ISBN 978-0-8308-2849-4, pp. 124–5.

- ^ Larsen, Peter (February 22, 2023). "'Jesus Revolution' tells the true story of Christian hippies and an Orange County church". Daily News. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c W. K. McNeil, Encyclopedia of American gospel music, Psychology Press, 2005, ISBN 0-415-94179-2, ISBN 978-0-415-94179-2, p. 59.

- ^ a b Richardson, James T. (2004). Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, (2004) Springer, ISBN 0-306-47887-0. ISBN 9780306478871. Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ^ Bill (Wam957). "Jesus Freaks 4 (part of my collection of rad videos of early 70's Jesus freaks on the Kathryn Kuhlman show)". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ John Wimber. Power Evangelism (Stodder and Houghton, London) - Page 36.

- ^ David A. Roozen, James R. NiemanBalmer (May 2, 2005). Church, Identity, and Change: Theology and Denominational Structures in Unsettled Times - Page 134. ISBN 9780802828194. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Bill (May 2, 2005). A Short History of the Association of Vineyard Churches. ISBN 9780802828194. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ Barkonsty. "trailer for documentary FRISBEE". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ Lonnie Frisbee with Roger Sachs, Not By Might, Nor By Power:Set Free,ISBN 0-9785433-5-1, p23-24

- ^ Lonnie Frisbee with Roger Sachs, Not By Might, Nor By Power:Set Free,ISBN 0-9785433-5-1, p210-211

- ^ "Video of Lonnie Frisbee Memorial Service at Crystal Cathedral, Chuck Smith, Phil Aguilar and guests..." YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ "GARDEN GROVE : Funeral Services for 'Hippie Preacher'". March 18, 1993. Retrieved April 11, 2019 – via LA Times.

- ^ "Documentary on Hippie Preacher Receives Emmy Award Nomination". Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ Mike Rimmer, "Larry Norman - Frisbee", Cross Rhythms (September 8, 2005 ), http://www.crossrhythms.co.uk/products/Larry_Norman/Frisbee/13328/; Jim Böthel, "Frisbee (2005)", http://www.meetjesushere.com/Frisbee_CD.htm Archived June 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jim Böthel, "Slinky (2005)", http://www.meetjesushere.com/slinky.htm Archived June 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading[edit]

- Young, Shawn David (2005). Hippies, Jesus Freaks, and Music. Ann Arbor: Xanedu/Copley Original Works. ISBN 1-59399-201-7.

External links[edit]

- Lonnie Frisbee at Find a Grave

- Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher, official site

- Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher at IMDb

- Lonnie Frisbee's testimony (preaching) on Mother's Day at Pastor John Wimber's Church, May 11, 1988, part 2; audio only with extensive photo slideshow. It is believed by some that this very meeting inspired the Vineyard Church movement (trailer on video gives date of 5-11-88, however vineyardusa.org states that this occurred in 1980).

- Lonnie Frisbee ministering at Tom Stipe's Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Denver, Colorado

- Lonnie Frisbee related videos on YouTube

- photo of Frisbee

- Understanding Ministries -- Lonnie Frisbee : The Problem of Charismatic Hypocrisy by Paul Fahy, a theological criticism of charismatic religion allowing 'emotion' to triumph over doctrine, using Lonnie Frisbee as case study and example.

- Interview with Connie Frisbee discussing Lonnie in response to Frisbee:The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher

- American evangelicals

- American Charismatics

- American Christian mystics

- Members of the Calvary Chapel

- American Protestant ministers and clergy

- Prophets in Christianity

- Jesus movement

- Protestant mystics

- People from Costa Mesa, California

- People from Novato, California

- LGBT people from California

- LGBT Protestant clergy

- AIDS-related deaths in California

- 1949 births

- 1993 deaths

- 20th-century evangelicals

- 20th-century Christian mystics

- Association of Vineyard Churches