John Forester (cyclist)

John Forester | |

|---|---|

| Born | 7 October 1929 Dulwich, London, England |

| Died | 14 April 2020 (aged 90)[1] San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Parent |

|

| Website | www.johnforester.com |

John Forester (7 October 1929 – 14 April 2020) was an English-American industrial engineer, specializing in bicycle transportation engineering. A cycling activist, he was known as "the father of vehicular cycling",[2] for creating the Effective Cycling program of bicycle training along with its associated book of the same title, and for coining the phrase "the vehicular cycling principle" – "Cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles". His published works also included Bicycle Transportation: A Handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers.[3]

Early life[edit]

Born in East Dulwich, London, England, Forester was the elder son of the writer and novelist C. S. Forester and his wife Kathleen. He moved with his family to Berkeley, California, in March 1940 and attended public schools there until after his parents' divorce, when he finished high school at a preparatory school on the East Coast.[4] He later attended the University of California at Berkeley,[4] starting as a physics major, but graduating with a bachelor's degree in English in August, 1951.[citation needed] Following a brief stint in the U.S. Navy in the early 1950s during the Korean War, Forester eventually settled in California to become, as he described it, "an industrial engineer,[5] a senior research engineer, a professor, and, of all things, an expert in the science of bicycling".[4]

In April 1966, Forester's father died. The unexpectedly large estate, its contents, and its disposition proved to Forester that his father, whom he had loved and admired, had consistently lied to him for years, and strongly suggested evidence of another secret life. That discovery was a traumatic experience, and led to his two-volume biography of his father, Novelist and Story Teller: The Life of C. S. Forester.[6][7][better source needed]

Cycling advocacy[edit]

Forester was a passionate cyclist from childhood.[4] He became a cycling activist in 1971, after being ticketed in Palo Alto, California for riding his bicycle on the street instead of a recently legislated separate bikeway for that section of the street, the sidewalk. He contested the ticket and the city ordinance was overturned.[9] His first published article—the first of his many publications on alternatives to bikeways over the following four decades—appeared in the February 1973 issue of Bike World, a regional Northern California bimonthly magazine.[10]

1972 opposition to bikeways and beginnings of vehicular cycling advocacy[edit]

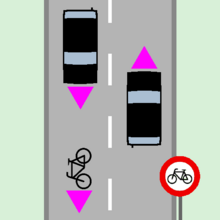

In 1972, the City of Palo Alto initiated the development of a bicycle network by implementing various types of bike lanes and routes. This caught Forester's attention, who expressed concerns about mandatory bike lane usage and the potential risks associated with protected bike lanes.

Forester held the belief that bike lanes would heighten risks associated with turning motorists, parked vehicles' doors being opened, and bicyclists making left turns. Additionally, he argued that bike lanes would delegitimize a bicyclist's right to operate on a street. To support his claim that protected bike lanes were dangerous, Forester conducted an anecdotal experiment. He rode his bicycle on a sidewalk designated for bicycle use at roadway cycling speed and attempted to make a left turn across all lanes of traffic from the sidewalk at that speed. He recounted this experience as "the one valid test of a sidepath system," stating that sidepath-style bikeways were "about 1,000 times more dangerous than riding on the same roads." Forester utilized this experience and his engineering background to oppose bikeways, contending that sidewalks, sidepaths, and protected bike lanes were hazardous and would increase liability for designers and cities in the event of a crash.

These experiences would later lead him to author Effective Cycling, the Cyclist Traffic Engineering Handbook and popularize the concept of vehicular cycling through articles in Bicycling magazine.[11]

1978 CalTrans guide influence and 1981 AAHSTO Bike Guide adoption[edit]

Forester’s vehicular cycling advocacy continued through the 1970s, with the 1978 CalTrans Bicycle Guide being heavily influenced by his Cycling Traffic Engineering Handbook. The guide de-emphasized bikeways, stating that roads were sufficient to accommodate shared use by bicyclists and motorists, and that common conflicts encountered by cyclists and motorists were due to improper behavior that could only be corrected through effective education and enforcement. [11]: 42

The vehicular cycling guidance espoused by the CalTrans Bicycle Guide was later adopted into the 1981 AASHTO Bike Guide, which prohibited protected bicycle lanes and repeated the vehicular cycling claim that bicycle lanes "tend to complicate both bicycle and motor vehicle turning movements at intersections". [11]: 39 This advice would remain until the 2012 AASHTO Bike Guide, where more extensive bike lane guidance was introduced following further research indicating safer outcomes associated with protected bike lanes. [11]: 44

Views on protected bicycle infrastructure[edit]

Every facility for promoting cycling should be designed for 30 mph (48 km/h). If it is not, it will not attract the serious cyclist and hence it will not be an effective part of the transportation system. A facility that is designed only for childlike and incompetent cyclists encourages the 'toy bicycle' attitude and discourages cycling transportation.

John Forester, [3]: 306

Forester gained significant recognition for his staunch opposition to protected bicycle infrastructure as documented in the book Pedaling Revolution. The aggressive manner in which he presented his arguments was observed to create unease among both supporters and opponents, who were taken aback by the forcefulness of his attacks on his adversaries. According to a transportation planner mentioned in the same source, Forester's argumentative style was characterized as "shrill and nasty" with another quipping that Forester's arguments would have been more effective if he had simply passed his treatise under the door avoiding public contact. He often employed pointed criticism, occasionally insinuating that his opponents lacked integrity or were involved in dishonest practices.[12]

He advanced a cyclist inferiority hypothesis that posits that there is a societal belief that cyclists are inferior road users and that this belief is perpetuated by a propaganda campaign led by motordom to frighten cyclists off the road. He argued that this campaign began in the 1920s and has continued to the present day, resulting in a culture of cycling inferiority. Forester also asserted that this belief is not factually based, and that cyclists who feel genuinely afraid of motor traffic are not riding properly or have not learned how to ride properly.[13]

In addition to criticizing protected bikeways, Forester extended his critique to the bikeway movement and its supporters whom he accused of promoting the cyclist inferiority hypothesis. He compared this hypothesis to the traditional religions of New Guinea tribes in that both lacked supporting data for their beliefs. He argued that the hypothesis had been the basis for public cycling policy for decades and had significant emotional influence on its advocates. He suggested that psychological analysis was needed to understand the beliefs associated with this hypothesis, as a purely traffic engineering perspective could not fully account for its effects. [3]: 106

Forester's critique of bikeways included a focus on how intersections were handled. He argued that there was no safe way for bikeways to run through intersections, specifically criticizing the European cyclist ring model where cyclists ride around the periphery of the intersection. Forester believed that this approach, which he described as a consequence of protected bikeways, had a high potential for conflicts with motor traffic at every turn. [3]: 318

When discussing comparisons between Dutch and American cycling, Forester dismissed such notions. He argued that the historical development and urban structure of cities like Amsterdam created fundamental differences in transportation patterns compared to American cities. While he acknowledged that physical infrastructure changes were made in the Netherlands to accommodate cycling and manage motor traffic, he attributed these changes primarily to the unsuitability of the cities for mass motor traffic rather than a deliberate focus on safety design. [13] He did not have personal experience cycling in the Netherlands. [12]: 85

Criticism[edit]

Many governmental and professional organizations, both in the United States and in other countries, recognize the inherent differences between a person driving a car and a person riding a bicycle and consider separated bicycle facilities to be best practice for promoting safety and adoption of cycling as a means for daily transportation.[14]

CPSC legal challenges[edit]

In May 1973, his focus broadened as the Food and Drug Administration (later the Consumer Product Safety Commission, or CPSC) issued extensive product safety regulations for bicycles. Originally intended only for children's bicycles, the regulations were soon expanded to include all bicycles except for track bikes and custom-assembled bicycles. That October, Forester published an article in Bike World denouncing both the California Department of Transportation and the CPSC.[15] He targeted the new CPSC regulations, especially the "eight reflector" system, which required front, rear, wheel and pedal reflectors. The front reflector replaced the bicycle headlight. Forester argued that motor vehicle drivers about to cross the path of the cyclist would not see the cyclist because the headlights of their motor vehicle did not shine onto the front reflector of the bicycle, often resulting in a crash. (Only if the bicycle was directly in front of the car and only if the bicycle was headed the wrong way, would the car's headlights illuminate the bicycle's front reflector, until the inevitable head-on crash.)

After the rules were finalized, Forester sued the CPSC. Acting as his own lawyer (pro se), Forester did not understand that United States federal law did not grant jurisdiction to the appeals court to review the technical merit of the rules (a so-called "de novo" review) unless the procedure used to create the rules was flawed. The CPSC argued that a challenger must prove the process was "arbitrary and capricious." The judge ordered a de novo review of the rules; threw out four of them, but left the "eight reflector" standard untouched.[16] Forester, emboldened by this partial success, proceeded to launch further challenges to administrative rules in court, but did not duplicate that early success. His legal advocacy remains highly controversial.[17][18]

Cycling safety education[edit]

In addition to legal advocacy, Forester was known for his theories regarding cycling safety.[19] His Effective Cycling educational program, developed after his research which claimed that integrating motorists and educated cyclists reduced accidents more than creating separate bicycle lanes, was implemented by the League of American Bicyclists (formerly, the League of American Wheelmen) until Forester withdrew his permission for that organization to use the name.[19]

Death[edit]

Forester died of complications related to a lingering flu on April 19, 2020, at the age of 90.[20]

Bibliography[edit]

- Statistical Selection of Business Strategies Chicago, Richard D. Irwin, 1968 Lib Cong 67-17054

- Bicycle Transportation (First edition, 1977; Second edition 1994, The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-56079-8)

- Effective Cycling (First edition, 1976; Sixth edition, MIT Press, 1993, ISBN 0-262-56070-4), 7th (2012) ISBN 0262516942

- Effective Cycling Program, Effective Cycling Instructor's Manual, the film Bicycling Safely On The Road (Iowa State University, 1978)

- Effective Cycling, The Movie, (Seidler Productions, 1992)

- Novelist & Story Teller, The Life of C. S. Forester. Lake Oswego, OR: eNet Press, 2013. Ebook reprint of self-published (2000) two-volume biography of his father.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Reid, Carlton, (23 April 2020),"Death Of A ‘Dinosaur:’ Anti-Cycleway Campaigner John Forester Dies, Aged 90" https://www.forbes.com/sites/carltonreid/2020/04/23/death-of-a-dinosaur-anti-cycleway-campaigner-john-forester-dies-aged-90/ Forbes Magazine

- ^ Aschwanden, Christie (2 November 2009). "Bikes and cars: Can we share the road?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

Forester is the father of the "vehicular cycling" movement -- a philosophy that views the bicycle as a form of transportation that belongs on the streets alongside cars.

- ^ a b c d Forester, John (1994). Bicycle Transportation: A Handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers (Second ed.). Preface: MIT Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-262-56079-5.

This book is the third form of my book on cycling transportation engineering. A first version appeared under the title of Cycling Transportation Engineering Handbook (Custom Cycle Fitments, 1977), and the first formal edition was Bicycle Transportation (The MIT Press, 1983).

- ^ a b c d Forester, John. My history Archived 20 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Forester Website. Accessed November 1, 2007.

- ^ State of California, Department of Consumer Affairs. "John Forester, Industrial Engineer, License # 236". Board of Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors and Geologists.

- ^ Forester, John (2000). Novelist & Storyteller: The Life of C. S. Forester (2 volumes) (first ed.). Lemon Grove, CA: John Forester. ISBN 978-0940558045.

- ^ Forester, George. "We publish high-quality ebooks of many 20th century bestselling authors, such as Niven Busch, Taylor Caldwell, Thorne Smith and C.S. Forester". enetpress.com. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Reid, Carlton (2017). "The Rise and Fall of Vehicular Cycling". Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling. Island Press/Center for Resource Economics. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-61091-817-6.

- ^ Mappes, Jeff (2009). Pedaling Revolution: How Cyclists Are Changing American Cities. Portland, OR: Oregon State University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0870714191.

- ^ Forester, John (February 1973). "What about Bikeways?". Bike World: 36–37. ISSN 0098-8650.

- ^ a b c d Schultheiss, William; Sanders, Rebecca L.; Toole, Jennifer (18 October 2018). "A Historical Perspective on the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities and the Impact of the Vehicular Cycling Movement". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2672 (13). SAGE Publications: 38–49. doi:10.1177/0361198118798482. ISSN 0361-1981. S2CID 115902607.

- ^ a b Mapes, Jeff (2009). Pedaling Revolution. Oregon State University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-87071-419-1.

- ^ a b Flax, Peter (24 April 2020). "Vehicular Cycling Advocate John Forester Dies at 90". Bicycling. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Mentjes, Dean (December 2023). "9A.01.03". Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (PDF) (Report) (11th ed.). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. p. 1047. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

Bicyclists are also vulnerable road users who have little to no protection from crash forces.

- Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary (February 2019). "1". Bikeway Selection Guide (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. p. 3. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

Multiple studies show that the presence of bikeways, particularly low-stress, connected bikeways, positively correlates with increased bicycling. This in turn results in improvements in bicyclists' overall safety.

- Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary (February 2019). "4". Bikeway Selection Guide (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

Shared lanes or bicycle boulevards are recommended for the lowest speeds and volumes; bike lanes for low speeds and low to moderate volumes; and separated bike lanes or shared use paths for moderate to high speeds and high volumes.

- CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic Hull, Angela; O’Holleran, Craig (1 January 2014). "Bicycle infrastructure: can good design encourage cycling?". Urban, Planning and Transport Research. 2 (1): 369–406. doi:10.1080/21650020.2014.955210.

[The CROW Design Manual] is considered best practice.

- Urban Bikeway Design Guide (Report) (2nd ed.). Island Press. December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary (February 2019). "1". Bikeway Selection Guide (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. p. 3. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Forester, John (October 1973). "Toy Bike Syndrome". Bike World: 24–27. ISSN 0098-8650.

- ^ "Forester v. Consumer Product Safety Commission". 559 F. 2d 774 - Court of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia Circuit 1977. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Epperson, Bruce (2010). "The Great Schism: Federal Bicycle Safety Regulation and the Unraveling of American Bicycle Planning" (PDF). Transportation Law Journal. 37 (2). bookmark #8 of journal's PDF archive: 73–118. ISSN 0049-450X. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Forrester, John (2011). "Letter to the Editor: Review of the Great Schism" (PDF). Transportation Law Journal. 39 (1). bookmark #4 of journal's PDF archive: 31–51. ISSN 0049-450X. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Smith, David. The bicycle driver Archived 11 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Cranked Magazine #5, pp. 22–25. Accessed November 1, 2007.

- ^ "Requiem for a Heavyweight - John Forester - 1929-2020". 2 June 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

Further reading[edit]

- Schultheiss, William; Sanders, Rebecca L.; Toole, Jennifer (2018). "A Historical Perspective on the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities and the Impact of the Vehicular Cycling Movement". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2672 (13): 38–49. doi:10.1177/0361198118798482. S2CID 115902607.

External links[edit]

- John Forester's web site (archived)

- ProBicycle biography of John Forester

- John Forester talk "Bicycle Transportation Engineering" at Google headquarters, May 17, 2007 on YouTube 60 min. Closed captioning. (video)

- Effective Cycling: The Cure for Un-riding! Archived 14 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine Review by Cycle California! Magazine.