John Felton (assassin)

John Felton | |

|---|---|

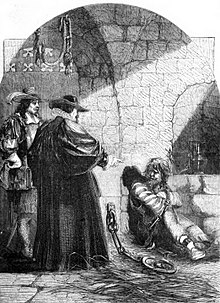

Felton in Prison, illustration from 'Cassell's illustrated history of England (1865)[1] | |

| Born | c. 1595 possibly Suffolk, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 29 November 1628 (aged 32–33) Tyburn, London, Kingdom of England |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Criminal status | Executed by hanging |

| Parents |

|

| Conviction(s) | Assassination of the Duke of Buckingham |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Death by hanging |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | English Army |

| Years of service | 1625–1627 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-Spanish War |

John Felton (c. 1595 – 29 November 1628) was a lieutenant in the English Army who stabbed George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, to death in the Greyhound Pub in Portsmouth on 23 August 1628.

King Charles I trusted Buckingham, who made himself rich in the process but proved a failure at foreign and military policy. Charles gave him command of the military expedition against Spain in 1625. It was a total fiasco with many dying from disease and starvation. He led another disastrous military campaign in 1627. Buckingham was hated and the damage to the king's reputation was irreparable. Buckingham's assassination by Felton was widely celebrated by members of the public in England, even after his execution.[2]

Early life[edit]

John Felton was born around 1595, possibly in Suffolk, to a family related to the Feltons of Playford in Suffolk and distantly related to Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel. His father, Thomas Felton, prospered as a pursuivant, one appointed to the task of hunting down those who refused to attend Anglican church services. His mother, Elanor, was the daughter of William Wight, the one-time mayor of Durham.[3]

The family's fortunes declined when Thomas' lucrative position was given to Henry Spiller in 1602. Thomas died around 1611, while he was imprisoned in the Fleet Prison for debt, although his widow was later able to secure a £100 per annum pension from the crown.[3] Felton's brother Edmund Felton also fell into debt trying to right the wrongs done against his father by Spiller, through petitions and printing and distribution of books and pamphlets.[4]

Army career[edit]

Nothing is known of John Felton's life until the mid-1620s, when he was an army officer. He served in the Cádiz Expedition of 1625, an attempt to capture the Spanish city of Cadiz that was backed by Buckingham. This resulted in a decisive Spanish victory, with 7,000 English troops and 62 out of 105 ships lost. Felton then served as a lieutenant in Ireland in 1626, during which time his commanding officer died and Felton tried, but failed, to be appointed as his replacement.[3]

In May or June 1627 Felton petitioned to be appointed a captain on Buckingham's military expedition of 1627, part of the Anglo-French War of 1627 to 1629. The purpose of the expedition was to capture the French fortress of Saint-Martin-de-Ré on the Île de Ré. This would secure the sea-approaches to the city of La Rochelle and encourage the French Huguenot population of the city to rebel against the French crown.[5]

Felton had connections in political circles but despite help from two Members of Parliament, Sir William Uvedale and Sir William Beecher, his initial request to join the expedition was turned down. Two months later he was appointed a lieutenant with the second wave of troops that left for the Île de Ré in August 1627.[3]

The expedition was a disaster for the English; the troops were ill-supplied and lacked the large artillery needed for the siege they laid at Saint-Martin-de-Ré. Many were lost on 27 October, during a final, desperate assault on the fortress of Saint-Martin, which failed because the attackers' siege ladders were shorter than the walls of the fortress. The English evacuated soon after, losing 5,000 out of 7,000 troops during the campaign.[citation needed]

After returning to England Felton lived in London for nine months. Although his mother, brother and sister lived in the city he did not stay with them but lived in a lodging house.[3] Those who encountered him during this time later described him as being taciturn and melancholic. His sister recalled that, since his return from Ré, Felton had been "much troubled by dreams of fighting".[3] This was possibly indicative of what would be described as post-traumatic stress disorder in modern terms. During this time Felton submitted petitions to members of the Privy Council over two matters, £80 of back-pay he believed he was owed and his promotion to captain, which he believed he had been unfairly denied. He had no success in resolving these grievances and came to believe the Duke of Buckingham was responsible for both of them.[citation needed]

Assassination of Buckingham[edit]

Buckingham was hugely unpopular in the land for the national disgrace of defeat by the French, although with the help of the king, Charles I, he had avoided legal moves against him by Parliament for corruption and incompetence. By August 1628 Felton had come to believe that his personal grievances against Buckingham were part of a larger picture of treacherous and wicked governance of England by the Duke. He resolved to kill Buckingham and after saying goodbye to his family travelled to Portsmouth.[3] Buckingham was staying there while trying to organise a new military campaign.[citation needed]

On the morning of Saturday 23 August Buckingham left his lodgings, the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth, after having breakfast. Felton was able to make his way through the crowd that surrounded Buckingham and stabbed him in the chest with a dagger. He missed a chance of escape in the ensuing chaos and shortly after the murder he presented himself before the crowd that had gathered and, expecting to be well received, announced his guilt. He was immediately arrested and taken before magistrates, who sent him to London for interrogation.[citation needed]

Felton's case[edit]

The authorities were convinced Felton had not acted alone and were anxious to get from him the names of any accomplices.[3] The Privy Council attempted to have Felton questioned under torture on the rack but the judges resisted, unanimously declaring its use to be contrary to the laws of England.[7]

While the truth of this story is contested, and indeed widely doubted, it remains the case that the Privy Council never issued a torture warrant again, and the last warrant under the Royal Signet was issued in 1640.[8] Indeed in 1641 the Star Chamber was abolished by the Habeas Corpus Act 1640.

Aftermath[edit]

The unpopularity of the Duke meant Felton's action was met with widespread approval. While he was awaiting trial it was celebrated in poems and pamphlets. Copies of written statements he carried in his hat during the assassination were also widely circulated.[3] A poem by the Oxford scholar and cleric Zouch Townley claimed that Felton had saved England and King Charles from the corruption of Buckingham's politicking.[9] The number of surviving copies of this work suggests it was widely circulated. However contemporary reports state Townley fled to Holland after it had become known he was the author.[10] An anonymous poem, Upon the Duke's Death, begins

The Duke is dead, and we are rid of strife

by Felton's hand that took away his life

The work goes on at length with an argument that Buckingham's assassination was not even a crime but that the Duke himself had been a criminal who had placed himself above the law.[11]

A rotten member, that can have no cure,

Must be cut off to save the body sure

Other works contrasted the Duke, who was claimed to be popish, cowardly, effeminate and corrupt, with Felton, who was described as Protestant, brave, manly and virtuous.[3] The writer Owen Feltham described Felton as a second Brutus.[12]

The son of Alexander Gill the Elder was sentenced to a fine of £2,000 and the removal of his ears after being overheard drinking to the health of Felton and stating that Buckingham had joined King James I in hell. However these punishments were remitted after his father and Archbishop Laud appealed to King Charles I.[14] After being tried and found guilty Felton was hanged at Tyburn on 29 November 1628.[3] In a miscalculation by authorities, his body was sent back to Portsmouth for exhibition where, rather than becoming a lesson in disgrace, it was made an object of veneration. A gulf was revealed between a public who revered Felton and the authorities that punished him.[3]

There are 18th and 19th century accounts of a dagger, claimed to have been the one used by Felton, being on display at Newnham Paddox in Warwickshire.[15][16][13] Newnham Paddox was the family seat of the Earls of Denbigh and Buckingham's sister, Susan, had married William Feilding, 1st Earl of Denbigh. How the dagger (if authentic) came to be at Newham Paddox was explained by it being recovered after the assassination and sent to Buckingham's widow, Katherine Villiers, Duchess of Buckingham, who was also living there.[17]

In fiction[edit]

The Three Musketeers[edit]

Felton's assassination of the Duke was fictionalised in Alexandre Dumas, père's The Three Musketeers (1844) and features in several film adaptations of the novel.

In Dumas' novel, Felton is portrayed as a Puritan who serves the fictional Lord de Winter. Felton is entrusted by de Winter to guard Milady de Winter, the widow of de Winter's brother and a French spy. Milady's master, Cardinal Richelieu, has ordered her to have Buckingham murdered so that he will not aid the Huguenot cause in the city of La Rochelle. As she and Felton question each other she puts on a façade of sorrow and broken innocence, even pretending to be a Puritan like Felton and inventing a story of being drugged and raped by Buckingham. Milady manages to seduce Felton in a matter of days and they escape together. Felton is sent to stab Buckingham, which he then justifies on the grounds of his lack of promotion in order to protect Milady. However Felton realises that he has been deceived when Milady sails away without him, and he is left to be hanged for his crime.

In the 1961 French film Les Trois Mousquetaires, Felton was played by Sacha Pitoëff; in the 1969 film of the Three Musketeers Felton is played by Christopher Walken.

In the 1973 film The Three Musketeers and its 1974 sequel The Four Musketeers, Felton is played by Michael Gothard. Felton appears briefly in the first film as a Puritan servant of Buckingham[18] (Lord de Winter does not appear in the films). The second film portrays his gradual seduction by Milady at some length and then his assassination of Buckingham, carried out under her influence.[citation needed]

Other works[edit]

Felton is the central character in a play by the dramatist Edward Stirling. Called John Felton; or the Man of the People, it was first performed at the Royal Surrey Theatre in 1852.[19]

The Duke's assassination features in Philippa Gregory's novel Earthly Joys (1998). In Ronald Blythe's novel The Assassin (2004) Felton is depicted as a complex character whose motives for the assassination are altruistic.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ "Cassell's illustrated history of England". Cassell Petter & Galpin. 1865. p. 139. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Thomas Cogswell, "John Felton, popular political culture, and the assassination of the duke of Buckingham." Historical Journal 49.2 (2006): 357–385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bellany (2004)

- ^ "Edmund Felton's petitions for justice". committees.parliament.uk. 4 September 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Allen French, "The Siege of Ré, 1627.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, vol. 28, no. 116, 1950, pp. 160–168. online

- ^ "Cassell's illustrated history of England". Cassell Petter & Galpin. 1865. p. 138. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Jardine, David (1837). A Reading on the Use of Torture in the Criminal Law of England. London: Baldwin and Cradock. pp. 10–12.

- ^ Friedman, Danny (2006). "Torture and the Common Law" (PDF). European Human Rights Law Review (2): 180.

- ^ Hammond (1990) p. 60

- ^ Hutson, Lorna (2017). The Oxford Handbook of English Law and Literature, 1500–1700. Oxford University Press. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-19-966088-9.

- ^ Hammond (1990) p. 61

- ^ Woodbridge, Linda (2010). English Revenge Drama: Money, Resistance, Equality. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-139-49355-0.

- ^ a b Ireland, Samuel (1795). Picturesque Views on the Upper or Warwickshire Avon. p. 79.

Among other reliques of antiquity, I was shown by his lordship the dagger with which Felton stabbed the Duke of Buckingham: of this dagger I have annexed a sketch

- ^ Masson, David (1859). The life of John Milton: narrated in connexion with the political, ecclesiastical, and literary history of his time. Macmillan and Co. pp. 150–151.

- ^ Scott, John; Taylor, John (1828). The London Magazine. Hunt and Clarke. pp. 71–.

- ^ Neale, Erskine (1850). The Life-Book of a Labourer. p. 31.

Among the curiosities at Newnham is the knife with which Felton stabbed the Duke of Buckingham _____ was good enough to show it to me and to explain through what channel it had come into the possession of her family. The knife is large has two blades pointing right and left and is a very formidable weapon.

- ^ Neale, Erskine (1850). The Life-Book of a Labourer. p. 32.

The servant of the murdered duke picked up the dagger, and sent it to the duchess, who was a Denbigh! "An odd present to make to his widow," was the quiet remark of my condescending informant, "but that such was the fact, can be established by documents in the possession of the family, that are perfectly to be relied upon."

- ^ The Three Musketeers. 1973. Event occurs at 67min.

- ^ The British drama, illustrated. 1870. pp. 1192–.

- Bibliography

- Bellany, Alastair (2004). "Felton, John (d. 1628), assassin". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9273. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- —— "Libel in Action: Ritual, Subversion and the English Literary Underground, 1603–1642" in Tim Harris, The Politics of the Excluded, c. 1500–1800 (2001), contains a section about public responses to the assassination.

- Hammond, Gerald (1990). Fleeting Things: English Poets and Poems, 1616–1660. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674306252.

External links[edit]

- D'Israeli, Isaac. "Felton, the Political Assassin", Curiosities of Literature

- Memorials & Monuments in Portsmouth Cathedral: The Duke of Buckingham

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Felton, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–247.