Jiang Ziya

| Lü Shang | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Qi | |||||

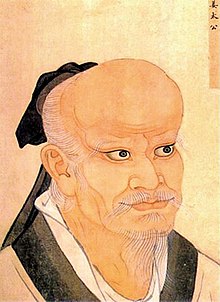

Jiang Ziya's portrait in the Sancai Tuhui | |||||

| Reign | 11th century BC | ||||

| Born | 1128 BC | ||||

| Died | 1015 BC (aged 113) | ||||

| Spouse | Shen Jiang | ||||

| Issue | Duke Ding of Qi Yi Jiang | ||||

| |||||

| Jiang Ziya | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 姜子牙 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Jiāng Zǐyá | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Jiang Shang | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 姜尚 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Jiāng Shàng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Lü Shang | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 呂尚 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吕尚 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǚ Shàng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Shangfu | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 尚父 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shàngfù | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Master Shangfu | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 师尚父 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shī Shàngfù | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Master Shangfu | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Titles | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Duke of Qi | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 齊太公 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 齐太公 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Qí Tàigōng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Grand Duke Jiang | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 姜太公 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Jiāng Tàigōng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Grand Duke Wang | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 太公望 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Tàigōng Wàng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Lü Wang | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 呂望 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吕望 | ||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Lǚ Wàng | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Jiang Ziya (fl. 12th century BC – fl. 11th century BC), also known by several other names, was a Chinese military general, monarch, strategist, and writer who helped kings Wen and Wu of Zhou overthrow the Shang in ancient China. Following their victory at Muye, he continued to serve as a Zhou minister. He remained loyal to the regent Duke of Zhou during the Rebellion of the Three Guards; following the Duke's punitive raids against the restive Eastern Barbarians or Dongyi, Jiang was enfeoffed with their territory as the marchland of Qi. He established his seat at Yingqiu (in modern Linzi).

Names[edit]

The first marquis of Qi bore the given name Shang. The nobility of ancient China bore two surnames, an ancestral name and a clan name. His were Jiang (姜) and Lü (呂), respectively. He had two courtesy names, Shangfu (尚父; lit. "Esteemed Father") and Ziya (子牙; lit. "Master Ivory, Master Tusk"), which were used for respectful address by his peers. The names Jiang Shang and Jiang Ziya became the most common after their use in the popular Ming-era novel Fengshen Bang, written over 2,500 years after his death.[1]

Following the elevation of Qi to a duchy, he was given the posthumous name 齊太公 Grand ~ Great Duke of Qi, on occasions left untranslated as "Duke Tai". It is under this name that he appears in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian.[2][3] He is also less often known as "Grand Duke Jiang" (姜太公; Jiang Taigong), the "Grand Duke's Hope" (Taigong Wang; 太公望), and the "Hoped-for Lü" (Lü Wang; 呂望).[1] as Jiang Ziya was seen as the sage – whom King Wen of Zhou's ancestor Duke Uncle Ancestor Lei (公叔祖类) (also titled 太公 "Great ~ Grand Duke") had prophesied about and hoped for – to help the Zhou prosper.[4]

Background[edit]

The last ruler of the Shang dynasty, King Zhou of Shang, was a tyrant who spent his days with his favorite concubine Daji and executing or punishing officials. After faithfully serving the Shang court for approximately twenty years, Jiang came to find King Zhou insufferable, and feigned madness in order to escape court life and the ruler's power. Jiang was an expert in military affairs and hoped that someday someone would call on him to help overthrow the king. Jiang disappeared, only to resurface in the Zhou countryside at the apocryphal age of seventy-two, when he was recruited by King Wen of Zhou and became instrumental in Zhou affairs.[5] It is said that, while in exile, he continued to wait placidly, fishing in a tributary of the Wei River (near today's Xi'an) using a barbless hook or even no hook at all, on the theory that the fish would come to him of their own volition when they were ready.[citation needed]

Hired by King Wen of the Zhou[edit]

King Wen of Zhou, (central Shaanxi), found Jiang Ziya fishing. King Wen, following the advice of his father and grandfather before him, was in search of talented people. In fact, he had been told by his grandfather, the Grand Duke of Zhou, that one day a sage would appear to help rule the Zhou state.

The first meeting between King Wen and Jiang Ziya is recorded in the book that records Jiang's teachings to King Wen and King Wu, the Six Secret Teachings (太公六韜). The meeting was recorded as being characterized by a mythic aura common to meetings between great historical figures in ancient China.[5] Before going hunting, King Wen consulted his chief scribe to perform divination in order to discover if the king would be successful. The divinations revealed that, "'While hunting on the north bank of the Wei river you will get a great catch. It will not be any form of dragon, nor a tiger or great bear. According to the signs, you will find a duke or marquis there whom Heaven has sent to be your teacher. If employed as your assistant, you will flourish and the benefits will extend to three generations of Zhou Kings.'" Recognizing that the result of this divination was similar to the result of divinations given to his eldest ancestor, King Wen observed a vegetarian diet for three days in order to spiritually purify himself for the meeting. While on the hunt, King Wen encountered Jiang fishing on a grass mat, and courteously began a conversation with him concerning military tactics and statecraft.[6] The subsequent conversation between Jiang Ziya and King Wen forms the basis of the text in the Six Secret Teachings.

When King Wen met Jiang Ziya, at first sight he felt that this was an unusual old man who is angling with a straight hook hanging out of water, and began to converse with him. He discovered that this white-haired fisherman was actually an astute political thinker and military strategist. This, he felt, must be the man his grandfather was waiting for. He took Jiang Ziya in his coach to the court and appointed him prime minister and gave him the title Jiang Taigong Wang ("The Great Duke's Hope", or "The expected of the Great Duke") in reference to a prophetic dream Danfu, grandfather of Wenwang, had had many years before. This was later shortened to Jiang Taigong. King Wu married Jiang Ziya's daughter Yi Jiang, who bore him several sons.

Attack of the Shang[edit]

After King Wen died, his son King Wu, who inherited the throne, decided to send troops to overthrow the King of Shang. But Jiang Taigong stopped him, saying: "While I was fishing at Panxi, I realised one truth – if you want to succeed you need to be patient. We must wait for the appropriate opportunity to eliminate the King of Shang". Soon it was reported that the people of Shang were so oppressed that no one dared speak. King Wu and Jiang Taigong decided this was the time to attack, for the people had lost faith in the ruler. The bloody Battle of Muye then ensued some 35 kilometres from the Shang capital Yin (modern day Anyang, Henan Province).

Jiang Taigong charged at the head of the troops, beat the battle drums and then with 100 of his men drew the Shang troops to the southwest. King Wu's troops moved quickly and surrounded the capital. The Shang King had sent relatively untrained slaves to fight. This, plus the fact that many surrendered or revolted, enabled Zhou to take the capital.

King Zhou set fire to his palace and perished in it, and King Wu and his successors as the Zhou dynasty established rule over all of China. As for Daji, one version has it that she was captured and executed by the order of Jiang Taigong himself, another that she took her own life, another that she was killed by King Zhou. Jiang Taigong was made duke of the State of Qi (today's Shandong province), which thrived with better communications and exploitation of its fish and salt resources under him.

As the most notable prime minister employed by King Wen and King Wu, he was declared "the master of strategy"—resulting in the Zhou government growing far stronger than that of the Shang dynasty as the years elapsed.

Personal views and historical influence[edit]

An account of Jiang Ziya's life written long after his time says he held that a country could become powerful only when the people prospered. If the officials enriched themselves while the people remained poor, the ruler would not last long. The major principle in ruling a country should be to love the people; and to love the people meant to reduce taxes and corvée labour. By following these ideas, King Wen is said to have made the Zhou state prosper very rapidly.

His treatise on military strategy, Six Secret Strategic Teachings, is considered one of the Seven Military Classics of Ancient China.

In the Tang dynasty he was accorded his own state temple as the martial patron and thereby attained officially sanctioned status approaching that of Confucius.

Family[edit]

Wives:

- Lady, of the Ma lineage (馬氏)

- Shen Jiang, of the Jiang clan of Shen (申姜 姜姓)

Sons:

- First son, Prince Ji (公子伋; 1050–975 BC), ruled as Duke Ding of Qi from 1025 to 975 BC

- Prince Ding (公子丁)

- Prince Ren (公子壬)

- Prince Nian (公子年)

- Prince Qi (公子奇)

- Prince Fang (公子枋)

- Prince Shao (公子紹)

- Prince Luo (公子駱)

- Prince Ming (公子銘)

- Prince Qing (公子青)

- Prince Yi (公子易)

- Prince Shang (公子尚)

- Prince Qi (公子其)

- Prince Zuo (公子佐)

Daughters:

- First daughter, Yi Jiang (邑姜)

- Married King Wu of Zhou (d. 1043 BC), and had issue (King Cheng of Zhou, Shu Yu of Tang)

His descendants acquired his personal name Shang as their surname.[7]

In Taoism[edit]

In Chinese and Taoist belief, Jiang Ziya is sometimes considered to have been a Taoist adept. In one legend, he used the knowledge he gained at Kunlun to defeat the Shang's supernatural protectors Qianliyan and Shunfeng'er, by using magic and invocations.[8] He is also a prominent character in the Ming-era Romance of the Investiture of the Gods, in which he is Daji's archrival and is personally responsible for her execution. The storyline present throughout the novel revolves around the fate of Jiang Ziya. He is destined to deify the souls of both humans and immortals who die in battle using the "List of Creation" (Fengshen bang, 封神榜), an index of preordained names agreed upon at the beginning of time by the leaders of the three religions. This list is housed in the "Terrace of Creation" (Fengshen tai, 封神臺), a reed pavilion in which the souls of the deceased are gathered to await their apotheosis. In the end, after defeating the Shang forces, Jiang deifies a total of 365 major gods, along with thousands of lesser gods, representing a wide range of domains, from holy mountains, weather, and plagues to constellations, the cyclical nature of time, and the five elements.

There are two xiehouyu about him:

- Grand Duke Jiang fishes – those who are willing jump at the bait (姜太公釣魚——願者上鉤), which means "put one's own head in the noose".

- Grand Duke Jiang investiture of the gods – omitting himself (姜太公封神——漏了自己), which means "leave out oneself".

Liexian Zhuan, a book on Taoist immortals, contains his short legendary biography:

呂尚者冀州人也。 |

Lü Shang was from Jizhou. |

| —Liexian Zhuan, with version according to Yiwen Leiju |

In popular culture[edit]

Manga[edit]

- The protagonist of Hoshin Engi, Taikoubou (Tai Gong Wang), is based on Jiang Ziya. However, his personality is quite comical.

Video games[edit]

- In the scenario "Chinese Unification" of the Civilization IV: Warlords expansion pack, Jiang Ziya is the leader of the State of Qi.

- He is also playable in video games Aizouban Houshin Engi, Hoshin Engi 2 and Mystic Heroes.

- Jiang Ziya is a playable character in Koei's Warriors Orochi 2. In the game, he is alternatively referred to as Taigong Wang. A stark contrast to the historical accounts however, would be that he is portrayed as a handsome young man, who is quite arrogant, although he is still a divinely gifted strategist and a good man at heart. He is often referred to by others, namely Fu Xi, Nüwa and Daji as "boy". The reason for his radically improvised design may be to emphasize his rivalry with Daji, whose character design depicts her as being young and beautiful as well. Their clashes are loosely inspired by the Fengshen Yanyi.

- In Final Fantasy XI, the item "Lu Shang's Fishing Rod" is awarded to players for catching 10,000 carp. It is noteworthy for its ability to catch both small and large fish, and is notoriously hard to break.

- In Final Fantasy XIV, Taikoubou is available in the Japanese language version of the game as a title for catching 100 different fish in A Realm Reborn, Heavensward or Stormblood areas.

- In the online game War of Legends, Jiang Ziya is a playable monk, with 45 "ability".

- In the popular game Eiyuu Senki, Tai Gong Wang is one female amongst the ancient heroes player will encounter in the game.

- In Dragalia Lost, Jiang Ziya is the name of an obtainable female Qilin adventurer.

- In December 2021, Fate/Grand Order revealed Taikoubou (one of Jiang Ziya's aliases) as a new obtainable servant in the game.

Food[edit]

- In Vietnamese cuisine, the grilled fish dish Chả cá Lã Vọng is named after Jiang, specifically after his title "Lü Wang" (Lã Vọng in Vietnamese).[9]

Films[edit]

- Jiang Ziya – 2020 Chinese 3D computer-animated fantasy adventure film directed by Cheng Teng and Li Wei. The plot is loosely based on the classic novel Investiture of the Gods, attributed to Xu Zhonglin.

Literature[edit]

- In The Poppy War trilogy by R. F. Kuang, Jiang Ziya is the name of a loremaster at the Sinegard Academy, and the protagonist's primary mentor figure.

See also[edit]

- Boyi and Shuqi

- Zhou Wang (Shang dynasty)

- King Wu of Zhou (Zhou dynasty)

- Chinese mythology

- Six Secret Teachings

- Caodaism

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Long Jianchun (龍建春) (2003). Discussion on Taigong's surname, clanname, given name and titles 《"太公"姓氏名号考论》. <苏秦始将连横>臆说之一. Taizhou Academy Newspapers (台州学院学报) 2nd semester, 2003.

- ^ Sima Qian. 齐太公世家 [House of Duke Tai of Qi]. Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). Guoxue.com. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Han Zhaoqi (韓兆琦), ed. (2010). Shiji (史记) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. pp. 2495–2510. ISBN 978-7-101-07272-3.

- ^ Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian "Hereditary House of the Grand Duke of Qi" quote: "於是周西伯獵,果遇太公於渭之陽,與語大說,曰:「自吾先君太公曰『當有聖人適周,周以興』。子真是邪?吾太公望子久矣。」故號之曰「太公望」,載與俱歸,立為師。" translation: "The Western Count of Zhou then went out hunting, and as a result met the Grand Duke [of Qi] on the Wei River's north bank, and talked [with the Grand Duke of Qi] and became greatly pleased, saying: "My lordly ancestor the Grand Duke himself had said: 'Just when one has a sage coming to/fit for Zhou, Zhou will prosper'. Are you truly that one? My Grand Duke had hoped for you long ago. [The Western Count] therefore called [the Grand Duke of Qi] 'Grand Duke's Hope', returned along with him in the same chariot, and honored him as teacher."

- ^ a b Sawyer, Ralph D. The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 27.

- ^ "T'ai Kung's Six Secret Teachings". Trans. Ralph D. Sawyer. In Sawyer, Ralph D., The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China. New York: Basic Books. 2007. p. 40.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland

- ^ Gu, Zhizhong (1996). Creation of the gods. New world Press. ISBN 7-80005-134-X. OCLC 467902421.

- ^ "The kings of chả cá". Thanh Nien Daily. 2011-06-03. Retrieved 2020-04-24.