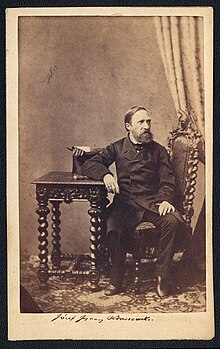

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski | |

|---|---|

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski | |

| Born | 28 July 1812 Warsaw, Duchy of Warsaw, Poland |

| Died | 19 March 1887 (aged 74) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Pen name | Bogdan Bolesławita, B.B., Kaniowa, Dr Omega, Kleofas Fakund Pasternak, and JIK |

| Occupation | Novelist, journalist and historian |

| Language | Polish |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Period | 19th century |

| Genres | Primarily novel, but also drama, poetry and non-fiction |

| Years active | 1830–1887 |

| Notable works | Chata za Wsią (The Cottage Beyond the Village, 1854) Hrabina Cosel (The Countess Cosel, 1874) Stara Baśń (An Ancient Tale, 1876) |

| Spouse |

Zofia Woroniczówna

(m. 1838–1887) |

| Children | 4 |

| Signature | |

| |

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski[a] (28 July 1812 – 19 March 1887) was a Polish novelist, journalist, historian, publisher, painter, and musician.

Kraszewski wrote over 200 novels and several hundred novellas, short stories, and art reviews, making him the most prolific writer in the history of Polish literature and one of the most prolific in world literature.

He is best known for his historical novels, including an epic series on the history of Poland, comprising twenty-nine historical novels; and for novels about peasant life, critical of feudalism and serfdom.

His works have been described as liberal-democratic but not radical, and as proto-Positivist.

Life[edit]

Early life[edit]

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski was born in Warsaw on 28 July 1812 to a family of Polish nobility (szlachta) of Jastrzębiec coat of arms.[1][2][3]: 221 He was the oldest son of Jan Kraszewski and Zofia and had four siblings, including artist Lucjan Kraszewski (born 1820) and writer Kajetan Kraszewski (born 1827).[1][4]: 145 [3]: 222

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski spent much of his youth in the house of his maternal grandparents in Romanów.[3]: 222

From 1822 to 1826 he attended school in Biała Podlaska (the Biała Academy); from 1826 to 1827, a gymnsium (secondary school) in Lublin; and in 1829, in Svislach in modern Belarus, he graduated from the Svislach gymnasium) after passing his matura examinations there.[1][3]: 222 [5]: 259

From 1829 he studied medicine, then literature and arts[further explanation needed], at Vilna University.[1][3]: 222 1830 marked his literary debut with several short stories ("Biografia sokalskiego organisty", "Kotlety. Powieść prawdziwa", and "Wieczór, czyli przypadki peruki"), followed a year later with his first novel (Pan Walery).[6][2][3]: 222 [5]: 259

While at university, he participated in a Polish-independence movement in support of the November 1830 Uprising. On 3 December 1830 he was arrested and was imprisoned until 19 March 1832.[1][3]: 222 Thanks to his family's intervention, he avoided being concripted into the Imperial Russian Army. After release, until July 1833 he lived in Vilna under police supervision. He was then allowed to go to his father's estate in Doŭhaje (Dołhe), near Pruzhany in Volhynia.[1][3]: 222 [5]: 259 He also spent time, at Horodziec, in the library of Antoni Urbanowski, whom he would visit often in future.[3]: 222

Landowner[edit]

In 1836 Kraszewski was nominated to join the faculty of Kiev University as professor of Polish language, but the nomination was vetoed by the Russian government, which considered him politically suspect.[1][3]: 222 [5]: 259 In 1851 he was offered a professorship at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, but this was again vetoed by the authorities, this time both Russian and Austrian.[1][3]: 223

In 1837 Kraszewski leased a farm in the village of Omelno.[1][3]: 222 Eventually he also became a landowner in several nearby villages: Gródek, 1840–1848; Hubin, from 1848; and Kisiele, from 1854. As time passed, he steadily lost interest in farming and focused on his literary work.[1][3]: 222 By the 1840s he was becoming well known as a prolific writer, and his works appeared in numerous Polish-language magazines and newspapers.[1][3]: 223 [5]: 259

On 10 June 1838 he married Zofia Woroniczówna, niece of Jan Paweł Woronicz, former Bishop of Warsaw. They had four children: Konstancja, born 1839; Jan, born 1841; Franciszek, born 1843; Augusta, born 1849.[1][3]: 222, 227

Kraszewski travelled extensively, visiting and staying for extended periods in Warsaw (1846, 1851,1855, 1859; in 1860 he bought a Warsaw townhouse, now known as the Kraszewski House), in Kiev (on numerous occasions), and in Odesa (1843, 1852).[3]: 222 [3]: 223 [5]: 259

In 1858 he travelled to Western Europe, visiting Austria, Belgium, Italy, Germany, and France. In Italy he was received by Pope Pius IX, who admonished him for his alleged liberal bias. This, however, likely heightened Kraszewski's critical view of the Holy State. His travels in the West also made him impatient with the feudal relations – particularly, serfdom – in eastern Poland.[3]: 223

In 1853, in an effort to better support and educate his four children, Kraszewski moved to his wife Zofia's inherited family estate near Zhytomyr, where he became, from 1856, school superintendent and director of the local theatre (Teatr Szlachty Wołyńskiej, or Zhytomyr Theater).[7]: 256 [3]: 222 [5]: 259 At first popular with the local nobility, he became less so on account of his support for the abolition of serfdom.[3]: 222 [5]: 259

As a result, in February 1860 he moved to Warsaw to take up the editorship of Gazeta Polska, a position he had accepted the previous year,[1][3]: 223 leaving his family in Zhytomyr. He grew increasingly distant from his wife, whom he would last see in 1863.[3]: 227

In 1858 he became a corresponding member of the Kraków Scientific Society.[3]: 223

In 1861 he became a member of the Delegacja Miejska, a patriotic civic organization.[where?][8] Kraszewski's political stance was fairly moderate; while supporting the cause of Polish independence, he saw armed struggle as premature, and initially supported conciliatory negotiations with Russian authorities represented by Aleksander Wielopolski.[3]: 224 [5]: 259 He has been described as "too red for the whites, too white for the reds".[by whom?][3]: 225–226 [5]: 259

As tensions grew, Kraszewski found it increasingly difficult to remain moderate. For his criticism of censorship in December 1862, the Russian authorities forced him to resign his editorship of Gazeta Polska and ordered him to leave Congress Poland. Following the eruption of the January 1863 Uprising, on 3 February 1863 he fled Warsaw.[1][3]: 224 [5]: 259

Saxony[edit]

Leaving the Russian partition, Kraszewski arrived in Dresden. His wife and children remained in the Russian partition, and he would support them financially for many years.[2][3]: 225 In Dresden he connected with other Polish refugees and supported the January 1863 Uprising and the cause of Polish independence in the European press (often presudonymously, to avoid trouble with the Saxon government).[9][5]: 260

With his own funds he published a weekly, Tydzień Polityczny, Naukowy, Literacki i Artystyczny, but eventually gave up on the endeavor due to financial difficulties.[1][3]: 225

He was effectively stateless, having lost his Russian citizenship, and used a false French passport until he received Austrian citizenship in 1866.[3]: 225 [5]: 260 From 1865 he travelled extensively in the Austrian partition of Poland, visiting Lviv, Kraków, Krynica, and Zakopane, and also visited Poznań in the Prussian Partition.[3]: 225 He was again considered but rejected for professorships of Polish literature, at the SGH Warsaw School of Economics in 1865 and the Jagiellonian University in 1867).[3]: 225

In 1868 he travelled to Switzerland, Italy, France, and Belgium. He published a travel account: Kartki z podróży 1858–1864 (Travels, 1858–1864).[10]

Beginning in the 1870s, he increasingly suffered from health problems.[3]: 225

His application for Saxon citizenship was approved in 1869 and for a time he ran a printing press in Dresden.[3]: 225 In 1871 he briefly campaigned to be elected a deputy from the Poznań region, but withdrew facing a strong opposition from the Polish conservative-clergy circles that he opposed in his newspaper polemics. In politics he kept representing the weak moderate faction.[3]: 225–226

He kept travellng, often invited to give lectures and attending academic conferences.[5]: 260 In 1872 he becsame the member of the Academy of Learning.[9] In 1873 he decided to become full-time writer, and this year alone he wrote ten novels and two academic texts.[2] He acquired a villa in Dresden.[3]: 225 In 1879 he celebrated the 50th anniversary of his literary career in several cities in Europe, including in Kraków in a large event (on 2 to 7 of October) during which he received the honorary degrees from Jagiellonian University as well as the Lviv University.[1][2][3]: 225 In 1880 he attempted to travel to Warsaw but was denied permission by the Russian authorities.[1][3]: 225 In 1882 he helped to found the educational institution Macierz Polska in Lwów.[9][3]: 225

He lived in Saxony until 1883, when he was arrested, while visiting Berlin, and accused of working for the French secret service, for whom he indeed worked since c. 1870.[1][3]: 225 After being tried by the Reichsgericht in Leipzig in May 1884, he was sentenced to three and a half years imprisonment in Magdeburg (in the Madgeburg fortress).[1][2] The case was seen as political, since Kraszewski was a vocal critic of German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, and Bismarck saw this as an opportunity to deal a blow to the Polish faction in Germany, even personally advocating a death sentence for the writer.[2][3]: 226 Due to poor health, high profile of the case covered in contemporary European press, and requests from clemency from Kraszewski's friends in high places (such as prince Antoni Wilhelm Radziwiłł and king of Italy, Umberto I), he was released on bail after year and a half in 1885.[1][2][3]: 226–227

Rather than remain in Magdeburg, as his bail required, he moved to a new home in Sanremo, Italy; where he hoped to recuperate in peace. This, however, violated the terms of his release and led to the German government issuance of an arrest warrant for him.[1][2] While in Sanremo, he witnessed the 1887 Liguria earthquake.[3]: 227 When the possibility of extradition arose, he decided to move to Lausanne, Switzerland, where he bought a new house; however, he never arrived in it - he died in Hôtel de la Paix in Geneva, from pneumonia, on 19 March 1887,[1][2][3]: 227 four days after his arrival there.[5]: 260 His remains were transferred to Kraków, and after a large funeral on 18 April 1887 he was interred at "Saint Michael the Archangel and Saint Stanislaus the Bishop and Martyr Basilica", commonly known as "Skałka" in the Crypt of Merit.[1][3]: 227 [5]: 260

Reception[edit]

He is credited with over 600[1] or 700[7]: 256 works, including 223 novels, 20 dramas and many short stories.[1][3]: 227 [5]: 260–261 He is considered one of the most prolific Polish writers,[1] and arguably one of the most prolific writers worldwide,[7]: 256 [11]: 17 and one of the first Polish wriers whose works were widely translated (several dozens of his works were translated to Russian, Czech, German, French, and French; about a dozen, to Serbo-Croatian; several, to English, Italian, Lithuanian and to varios Scandinavian languages).[1][5]: 261 His novels have helped to spread literacy in Poland, and were still considered popular in the mid-20th century[7]: 256–257 and early 21st century.[5]: 260

Czesław Miłosz, 1980 Nobel laureate Polish poet, in his The History of Polish Literature (1969) described him as best exemplifying the genre of historical novel in Polish literature.[7]: 256 Miłosz further noted that in Polish literature, Kraszewski founded the "new genre of fiction based upon documenbts and other sources where the faithful presentation of a given epoch is the main goal, and plot and characters are used simply as a bait for the readers". In popularizing Polish history, Miłosz drew a pararell between Kraszewski and Polish foremost painter, Jan Matejko, whose primary focus of works was likewise the history of Poland.[7]: 257

Works[edit]

Novels[edit]

He is best known for his novels. Those could be divided into four major subgenres: historical novels, novels about the life of peasants, novels about the life of nobility and novels about artists.[3]: 223 Out of those four, critics most often mention his historical and peasant novels.[3]: 223 [7]: 256–257 [11]: 17 [9]

His historical novels (94 total[3]: 227 ) include the epic series on the history of Poland, comprising twenty-nine historical novels in seventy-nine parts, covering the period of Polish prehistory (chronologically beginning with Stara Baśń, An Ancient Tale, 1876) to Kraszewski's present era of partitions of Poland Saskie ostatki (Saxon Remnants, 1890).[7]: 257 [11]: 17 [9][3]: 226 Also significant are the three "Saxon Novels" (the Saxon trilogy), written between 1873 and 1883 in Dresden.[9][3]: 226 Together, they create a detailed history of the Electorate of Saxony, from 1697 to 1763. Miłosz noted that the best of these are first two, Hrabina Cosel (The Countess Cosel, 1874) and Brühl (1875).[7]: 257

His "peasant" novels, critical of serfdom and feudalism, are also often mentioned among his important contributions. Miłosz called them his most popular works[7]: 257 and Wincenty Danek wrote that they are the works that have popularized his name.[3]: 223 That series includes nine positions, out of which the most important are Historia Sawki (The Story of Sawka, 1842), Ulana (1843), Ostap Bondarczuk (1847), Chata za Wsią (The Cottage Beyond the Village, 1854), Jermoła: obrazki wiejskie (Jermoła: Pictures from a Village, 1857) and Historja kołka w płocie (The Story of a Peg in a Fence, 1860).[7]: 257 [3]: 223–224 Danek also noted, referring to Historia Sawki, that Kraszewski's works were the first time Polish literature discussed the oppression of Ukrainian peasants by the Polish nobility.[3]: 224 Ulana in turn has been praised for the "a bold and innovative analysis of the experiences of a peasant woman wronged by her lord".[9]

Danek also praised Kraszewski's novels about the life of nobility, calling them groundbreaking for their criticism of nobility. As most important novels wit that theme he cited Latarnia czarnoksięska (Magical Lighthouse,1843-1844), Interesa familijne (Family Business, 1853), Złote Jabłko (Golden Apple, 1853), and Dwa światy (Two Worlds, 1855).[3]: 224

Examples of his works about the life of artists and the place of art in the wider society include Poeta i świat (The Poet and the World, 1839),[12][13] Sfinks (Sphinx, 1842), Pamiętniki nieznajomego (Diaries of the Unknown, 1846), and Powieść bez tytułu (Novel without a Title, 1855). Some of those works are partly auto-biographical.[3]: 223

While Danek described the above four subgenres as Kraszewski's major directions, he also noted that Kraszewski, a very prolific writer, has written novels representing all major contemporary genres: romances, adventures, comedies, satires, memoires and their pastiches, gawędas, crime novels, psychological novels, sensation novels, and others.[3]: 227–228

From the technical perspective, Danek noted that Kraszewski novels introduced elements of common speech to Polish literary language.[3]: 224, 228 With regards to Kraszewski's characters, Danek sees them as having relatively little psychological depth, but memorable due to vivid descriptions and mannierisms, and notes that Kraszewski was best at depicting strong female characters.[3]: 228

Other writings[edit]

Alongside novels, Kraszewski also wrote poetry, collected in Poezje (Poems, two volumes in 1838 and 1843), and Hymny boleści (Hymns of sorrow, 1857), as well as the lengthy poem-trilogy Anafielas (1843–1846). He also penned dramas. most notably the comedies Miód kasztelański (The Castellan's Honey. 1853) and Panie Kochanku (Mr. Lover, 1857). However, as noted by critics, Kraszewski was not particularly gifted in those dimensions.[3]: 224 [14]

In addition to his literary work, he was a contributor to many newspapers, journals and magazines, where he published works of fiction as well as reviews and articles on topics such as art, music and morality, and later, contemporary politics.[3]: 223 [2] Between 1841 and 1851 he published sixty volumes of the literary and scientific journal Athenaeum, printed in Vilna.[7]: 256 [15] From 1836 to 1849 he was a contributor to the Tygodnik Petersburski (St. Petersburg Weekly).[7]: 256 [3]: 223 From 1842 to 1843 he contributed to Pielgrzym.[3]: 223 Before 1859 he was a contributor to the Gazeta Warszawska.[3]: 224 He was the editor of the Gazeta Polska (1859–62, from 1861, renamed to Gazeta Codzienna).[9][3]: 223–224 In the 1860s and 1870s he wrote for, among others, Tygodnik Illustrowany, Kłosy, Bluszcz, Ruch Literacki, Tygodnik Mód i Powieści, Kraj, Biesiada Literacka, Dziennik Poznański, Wiek, and Kurier Warszawski.[3]: 227 [5]: 260

While his works of fiction are the most enduring, his scholarly endeavours, primarily in the fields of history (particularly the history of Lithuania, and art history) and literary criticism, produced not only journal articles but a number of monogaphs (Wilno od początków jego do roku 1750, 1840–42; Litwa, starożytne dzieje, ustway, język, wiara, obyczaje, pieśni, 1848; Litwa starożytna, 1850; Dante, 1869; Polska w czasie trzech rozbiorów, 1873–1875; Krasicki, 1879); collected volumes of his articles (Studia literackie, 1842; Nowe studia literackie, 1843; Gawędy o literaturze i sztuce, 1857); and collections of primary materials (Pamiętniki Stanisława Augusta Poniatowskiego, 1870; Listy Jana Śniadeckiego, 1878; Listy Zygmunta Krasickiego, 1882–83).

He was also an editor, supervising publication of works by Kazimierz Brodziński (Pisma, 1872–74) and translations of Shakespeare (Dzieła dramatyczne, 1875–77).[3]: 224, 227–228

Other arts[edit]

While Kraszewski is best remembered as a writer, he was also an illustrator (he illustrated many of his works) and a painter (he displayed some of his paintings at local art exhibitions, and some where exhibited at others after his death).[1][3]: 227 He also played piano and composed music (Pastusze piosenki, 1845).[3]: 228

He was also a collector, amassing a substantial collection of Polish drawings and etchings, which he sold in 1869 due to financial difficulties.[3]: 227–228

Themes[edit]

Kraszewski's early works describe the lives of ordinary people, and are thus a proto-Positivist critique of romantic traditions that focused on heroic individuals.[6][3]: 222 : 226 [9] Danek attributes his focus on reality to inspirations with classic novelists such as Charles Dickens, Honoré de Balzac and Nikolai Gogol. While his focus on history is similar to that of Walter Scott, Danek argues that it is sufficiently different to be considered not a copy of Scott's style. His early novels also show likely influence of Laurence Sterne, Fryderyk Skarbek. Jean Paul and E. T. A. Hoffmann.[3]: 223, 228

One of the major themes of his works was Lithuania, and his works, although written in Polish language, are seen as contributing to Lithuanian National Revival.[7]: 256 Another theme in his works was the criticism of feudal relationships, and a number of his novels feaured peasant and female heroes.[7]: 257 [11]: 17 [9] His works have been described as leaning liberal-democratic,[9] but not radical.[7]: 257 Danek writes that Kraszewski supported the ideal of egalitarianism.[3]: 228 He often criticized nobility, particularly aristocracy, as unproductive and degenerative, and praised peasantry and the middle class.[3]: 226, 228

His attitude to religion changed over time. He became more religious after marriage (his relatives and friends included bishops Jan Paweł Woronicz and Ignacy Hołowiński and priest Stanisław Chołoniewski), but over time he became opposed to more conservative values aligned with clergy and the church hierarchy (something for which he was criticized for by the Pope).[3]: 223, 225–226, 228 [5]: 259

In the realm of politics, he supported the cause of Polish independence, but opposed armed struggle, which in his literary works he thought unlike to succeed. He became more supportive of it in his newspaper polemics after the January Uprising started, effectively accepting it as a fait accompli.[3]: 225–226, 228 Some of his novels have been described as critical of Germany, reflecting a push against the policies of Germanization.[3]: 226 [16] Others were critical of Russia.[5]: 260

Remembrance[edit]

His works were adapted into numerous dramas; Stanisław Moniuszko composed music for the drama version of Anafielas third part, Witolorauda.[3]: 228

The first of his books to be adapted for film was Chata za wsią, adapted into Cyganka Aza (1926).[3]: 228 The second was Hrabina Cosel, resulting in Countess Cosel (1968), directed by Jerzy Antczak, with Jadwiga Barańska in the title role.[17][3]: 228 Twenty years later, in East Germany, the DEFA presented a six-part television series, the Saxon Trilogy, including a new version of Gräfin Cosel, directed by Hans-Joachim Kasprzik.[18] In 2003, Stara Baśń was adapted to the movie An Ancient Tale: When the Sun Was a God, directed by Jerzy Hoffman.[19]

Monuments to Kraszewski exist in Biała Podlaska (Józef Ignacy Kraszewski's bench in Biała Podlaska) and Krynica-Zdrój (Kraszewski's bench in Krynica-Zdrój); many other places feature memorial plaques dedicated to him.[5]: 260

Since 1960, his former home in Dresden has been the Kraszewski-Museum.[20][5]: 260 Another museum dedicated to him was opened in 1962 in Romanów (the Józef Ignacy Kraszewski Museum in Romanów).[1][5]: 260

Notes[edit]

- ^ In his works, he used a number of pseudonyms, including Bogdan Bolesławita, B.B., Kaniowa, Dr Omega, Kleofas Fakund Pasternak, and JIK.[3]: 222

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Tarkowski, Paweł. "KRASZEWSKI Józef Ignacy (1812-1887), pisarz, publicysta, wydawca, historyk, rysownik". Słownik biograficzny Południowego Podlasia i Wschodniego Mazowsza. Uniwersytet Przyrodniczo-Humanistyczny w Siedlcach. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Grzywacz, Marta (18 July 2016). "Józef Ignacy Kraszewski: osobisty wróg Bismarcka. Historia szpiegowska". Gazeta Wyborcza.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb Danek, Wincenty (1970). "Józef Ignacy Kraszewski". Polski słownik biograficzny (in Polish). Vol. 15. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich - Wydawawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk.

- ^ Antkowiak, Zygmunt (1982). Patroni ulic Wrocławia (in Polish). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. ISBN 978-83-04-00995-0.

Jan i Zofia mieli pięcioro dzieci, z których Józef Ignacy był najstarszy

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Roszkowska-Sykałowa, Wanda; Albrecht-Szymanowska, Wiesława (2001). "Kraszewski Józef Ignacy". In Loth, Roman (ed.). Dawni pisarze polscy od początków piśmiennictwa do Młodej Polski: przewodnik biograficzny i bibliograficzny. Vol. 2. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. ISBN 978-83-02-08101-9.

- ^ a b Zajkowska, Joanna (21 December 2023). "Kraszewski w Wilnie – jak się narodził pisarz". Bibliotekarz Podlaski Ogólnopolskie Naukowe Pismo Bibliotekoznawcze i Bibliologiczne (in Polish). 60 (3): 149–166. doi:10.36770/bp.826. ISSN 2544-8900.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Milosz, Czeslaw (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- ^ "Delegacja Miejska, Encyklopedia PWN: źródło wiarygodnej i rzetelnej wiedzy". encyklopedia.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Kraszewski Józef Ignacy". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Stożek, Joanna (2018). ""Kartki z podróży" Józefa Ignacego Kraszewskiego a poetyka reportażu". Zeszyty Prasoznawcze (in Polish). 4 (236): 778–792. doi:10.4467/22996362PZ.18.045.10403. ISSN 0555-0025.

- ^ a b c d Davies, Norman (24 February 2005). God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume II: 1795 to the Present. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-925340-1.

- ^ Jauksz, Marcin (2012). "Postacie poezji. Nad mottami "Poety i świata" Józefa Ignacego Kraszewskiego". Wiek XIX. Rocznik Towarzystwa Literackiego Im. Adama Mickiewicza (in Polish). XLVII (1): 377–390. ISSN 2080-0851.

- ^ Wojciechowska, Ewa (2012). "Bildung Nowoczesnego Poety. O Poecie i Świecie Józefa Ignacego Kraszewskiego / The Bildung of a Modern Poet: Józef Ignacy Kraszewski's The Poet and the World". Ruch Literacki; 2012; No 4-5. 53 (4–5): 433–450. doi:10.2478/v10273-012-0028-9. ISSN 0035-9602.

- ^ Kącka, Eliza (2012). "Człowiek według Smilesa. Kraszewski pozytywistów (Struve, Chmielowski, Orzeszkowa)". Wiek XIX. Rocznik Towarzystwa Literackiego Im. Adama Mickiewicza (in Polish). XLVII (1): 457–470. ISSN 2080-0851.

- ^ Roszkowska-Sykałowa, Wanda (1974). Athenaeum Józefa Ignacego Kraszewskiego, 1841-1851: zarys dziejów i bibliografia zawartości (in Polish). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

- ^ Danek, Wincenty (1963). "Sprawy słowiańskie w życiu i twórczości Kraszewskiego" [Slavic issues in Kraszewski's life and work] (PDF). Pamiętnik Literacki: Czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej (in Polish). 54 (2): 357–374.

- ^ "PISF - Jubileusz Jadwigi Barańskiej" (in Polish). Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ ""Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria": Wie eine Filmlegende entstand" ["Saxony's splendor and Prussia's glory": How a film legend came to be]. MDR KULTUR. 27 December 2020. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Lektura nieobowiązkowa - Recenzja filmu Stara baśń. Kiedy słońce było bogiem (2003)". Filmweb (in Polish). Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Kraszewski Museum | Museums of Dresden". museen-dresden.de. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

Further reading[edit]

- Elżbieta Szymańska/Joanna Magacz: Kraszewski-Museum in Dresden, Warschau 2006. ISBN 83-89378-13-2

- Zofia Wolska-Grodecka/Brigitte Eckart: Kraszewski-Museum in Dresden, Warschau 1996. ISBN 83-904307-3-8

- Elżbieta Szymańska/Ulrike Bäumer: Andenken an das Kraszewski-Museum in Dresden, ACGM Lodart, 2000

- Victor Krellmann: "Liebesbriefe mit ebenholzschwarzer Tinte. Der polnische Dichter Kraszewski im Dresdner Exil", In: Philharmonische Blätter 1/2004, Dresden 2004.

- Friedrich Scholz: Die Literaturen des Baltikums. Ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1990. ISBN 3-531-05097-4

- Henryk Szczepański: Gwiazdy i legendy dawnych Katowic – Sekrety Załęskiego Przedmieścia. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Śląsk, 2015. ISBN 978-83-7164-860-1

External links[edit]

- Detailed biography from the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary @ Russian Wikisource

- Works by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Józef Ignacy Kraszewski at Internet Archive

- Works by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Polish Literature in English Translation

- Kraszewski's Museum

- Detailed biography @ the Virtual Library of Polish Literature

- Józef Ignacy Kraszewski - biography and poems at poezja.org

- 1812 births

- 1887 deaths

- Writers from Warsaw

- Polish historical novelists

- Polish male novelists

- Polish male short story writers

- Polish opinion journalists

- 19th-century journalists

- Male journalists

- 19th-century Polish novelists

- 19th-century Polish male writers

- Polish political prisoners in the Prussian partition

- Polish political prisoners in the Russian partition

- 19th-century Polish painters

- Józef Ignacy Kraszewski