International draughts

International draughts starting position | |

| Genres | |

|---|---|

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | < 1 minute |

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonyms |

|

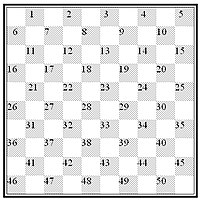

International draughts (also called international checkers or Polish draughts) is a strategy board game for two players, one of the variants of draughts. The gameboard comprises 10×10 squares in alternating dark and light colours, of which only the 50 dark squares are used. Each player has 20 pieces, light for one player and dark for the other, at opposite sides of the board. In conventional diagrams, the board is displayed with the light pieces at the bottom; in this orientation, the lower-left corner square must be dark.

History[edit]

According to draughts historian Arie van der Stoep, the 100 square draughts board came into use in the Netherlands between 1550 and 1600, and the number of pieces was extended to 2x20 between 1650 and 1700. The name "Polish draughts" was following a Dutch convention of the time that "unnatural" ideas were considered "Polish".[1]

Rules[edit]

The general rule is that all moves and captures are made diagonally. All references to squares refer to the dark squares only. The main differences from English draughts are: the size of the board (10×10), pieces can also capture backward (not only forward), the long-range moving and capturing capability of kings known as flying, and the requirement that the maximum number of men be captured whenever a player has capturing options.

Starting position[edit]

- The game is played on a board with 10×10 squares, alternatingly dark and light. The lower-leftmost square should be dark.

- Each player has 20 pieces. In the starting position (see illustration) the pieces are placed on the first four rows closest to the players. This leaves two central rows empty.

Moves and captures[edit]

- The player with the light pieces moves first. Then turns alternate.

- Ordinary pieces move one square diagonally forward to an unoccupied square.

- Enemy pieces can and must be captured by jumping over the enemy piece, two squares forward or backward to an unoccupied square immediately beyond. If a jump is possible it must be done, even if doing so incurs a disadvantage.

- Multiple successive jumps forward or backward in a single turn can and must be made if after each jump there is an unoccupied square immediately beyond the enemy piece. It is compulsory to jump over as many pieces as possible. One must play with the piece that can make the maximum number of captures.

- A jumped piece is removed from the board at the end of the turn. (So for a multi-jump move, jumped pieces are not removed during the move, they are removed only after the entire multi-jump move is complete.)

- The same piece may not be jumped more than once.

Crowning[edit]

- A piece is crowned if it stops on the far edge of the board at the end of its turn. When it reaches the edge but have the opportunity to jump backwards, he must do so, and is not crowned.[2] Another piece is placed on top of it to mark it. Crowned pieces, sometimes called kings, can move freely multiple steps in any direction and may jump over and hence capture an opponent piece some distance away and choose where to stop afterwards, but must still capture the maximum number of pieces possible.

Winning and draws[edit]

- A player with no valid move remaining loses. This occurs if the player has no pieces left, or if all the player's pieces are obstructed from moving by opponent pieces.

- A game is a draw if neither opponent has the possibility to win the game.

- The game is considered a draw when the same position repeats itself for the third time (not necessarily consecutive), with the same player having the move each time.

- A king-versus-king endgame is automatically declared a draw, as is any other position proven to be a draw.[citation needed]

These are extra rules accommodated in some tournaments and may vary:

- If, during 25 moves, there were only king movements, without piece movements or jumps, the game is considered a draw.

- If there are only three kings, two kings and a piece, or a king and two pieces against a king, the game will be considered a draw after the two players have each played 16 turns.[3]

- Before a proposal for a draw can be made, at least 40 moves must have been made by each player.[4][5]

Notation[edit]

Each of the fifty dark squares has a number (1 through 50).[6] Number 46 is at the left corner seen from the player with the light pieces. Number 5 is at the left corner seen from the player with the dark pieces.

Sport[edit]

The first world championship was held in international draughts in 1894. It was won by Frenchman Isidore Weiss, who held the title for eighteen years with seven world championship titles. Then, for nearly sixty years, the title was held by representatives from either France or the Netherlands, including Herman Hoogland, Stanislas Bizot, Marius Fabre, Ben Springer, Maurice Raichenbach, Pierre Ghestem, and Piet Roozenburg. In 1956, the hegemony of the French and the Dutch was broken: the champion was Canadian Marcel Deslauriers. In 1958, the USSR's Iser Kuperman became the world champion, beginning the era of Soviet domination in international draughts, a feat which would mirror their domination at chess around this time.

The official status of the world championships are held under the auspices of the World Draughts Federation (FMJD) since 1948. In 1998, the first World Championship was held in the format of the blitz. The first Women's World Championship was held in 1973. The first women's champion was Elena Mikhailovskaya from the Soviet Union. A World Junior Championship has been contested since 1971; the first winner was Nicholay Mischansky.

In addition to the World Championships, there is also a European Championships since 1965 (men) and 2000 (women).

The World Draughts Federation maintains a ranking.[7] As of 1 January 2022[update], the men's list is headed by Alexander Georgiev from Russia, and the women's list is headed by Natalia Sadowska from Poland.

Computers[edit]

Computer draughts programs have been improving every year. First draughts programs were written in the mid-1970s.[8] The first computer draughts tournament took place in 1987.[9] In 1993, computer draughts program Truus ranked about 40th in the world.[10] In 2003 computer draughts program Buggy beat world number 8 Samb.[11] In 2005, the 10-time world champion and 2005 World champion, Alexei Chizhov, commented that he could not beat the computer, but he also would not lose to the computer.[12] In 2010, the 9 piece endgame database was built.[13]

Schwarzman beat Maximus (2012)[edit]

Alexander Schwarzman beat computer program Maximus on April 14, 2012. Schwarzman won game 2 in the 6-game match. The other 5 games were draws. Schwarzman was world champion in 1998, 2007, and 2009. Jan-Jaap van Horssen of the Netherlands wrote Maximus. Maximus used a six-piece endgame database. The computer was an Intel core i7-3930K at 3.2 GHz 32 gigabytes memory; it had six cores with hyperthreading. The average search depth was 24.5 ply. The average number of moves evaluated per second was 23,357,000. The average search time was 3 minutes and 52.98 seconds.[14][15]

List of top international draughts programs[edit]

- Scan by Fabien Letouzey

- KingsRow[16] by Ed Gilbert

- Dragon Draughts[17]

- Damage by Bert Tuyt

- Damy

- Maximus

Some older well known programs are:

- Truus

- Flits

Computer tournament winners[edit]

- Culemborg 2013 Dragon Draughts

- Culemborg 2012 Dragon Draughts[18]

- Culemborg 2011 Maximus[19]

- Culemborg 2010 Damage[20]

- Culemborg 2009 Damy[21]

See also[edit]

- Dameo

- Hexdame – international draughts rules applied to a hexagonal board

- List of Draughts European Championship winners

- List of Draughts World Championship winners

- List of women's Draughts European Championship winners

- List of women's Draughts World Championship winners

References[edit]

- ^ Van der Stoep, Arie (2011). "History of Draughts". Koninklijke Nederlandse Dambond.

- ^ Rule 4.13 of the World Draughts Federation Annex

- ^ "Jeu de dames - FFJD - Fédération Française" (in French). Ffjd.fr. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "Official FMJD rules for competitions". fmjd.org. 2014-02-19.

- ^ "Official FMJD rules for competitions" (in French). fmjd.org. 2014-02-19.

- ^ "Dammen". Damweb.nl. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "FMJD - World Draughts Federation".

- ^ "Orange". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Orange". Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Searching for Solutions in Games and Artificial Intelligence By Louis Victor Allis. Chapter 6 section 3.8 page 169" (PDF). Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "The draughts program Buggy". Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Who wins a match between the world champion and a computer? - World Draughts Forum". Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Gilbert, Ed. "9 piece endgame database". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Maximus – Schwarzman: digitale gladiator tegen keizer van vlees en bloed" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ van Horssen, Jan-Jaap. "Maximus vs. Schwarzman draughts match". Draughts, Computer, Internet. World Draughts Forum. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Kingsrow Ed Gilbert site

- ^ "Dragon draughts - computer program". mdgsoft.home.xs4all.nl. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "Sneldamkampioenschap van Nederland 2012". Home.kpn.nl. 2012-09-16. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "Sneldamkampioenschap van Nederland 2011". Home.kpn.nl. 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "Sneldamkampioenschap van Nederland 2010". Home.kpn.nl. 2010-09-12. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ^ "Sneldamkampioenschap van Nederland 2009". Home.kpn.nl. 2009-09-13. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

External links[edit]

- FMJD (World Draughts Federation) Rules and Regulations

- ICAONA International Checkers Association of North America