Ida Boy-Ed

Ida Boy-Ed | |

|---|---|

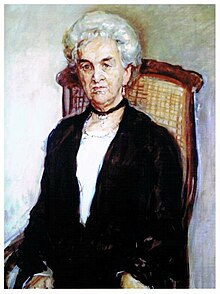

Ida Boy-Ed by Max Slevogt | |

| Born | Ida Cornelia Ernestina Ed 17 April 1852 Bergedorf |

| Died | 13 May 1928 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | Burgtorfriedhof |

| Nationality | German |

Ida Boy-Ed (17 April 1852 – 13 May 1928) was a German writer. A supporter of women's issues, she wrote widely-read books and newspaper articles.

Early years[edit]

Ida Cornelia Ernestina Ed was born in Bergedorf in 1852 to a supportive family who encouraged her to write. Her father had started his own newspaper business. Her creation of short novels and other literary works was deterred when she married Carl Johann Boy[1] at the age of seventeen.[2]

Career[edit]

Over her husband's objections in 1878, she moved out of the house she shared with his family. She took her eldest son, Karl, with her to Berlin where she intended to make her living by writing. Despite already being a published author of serialised novels and having experience in newspaper writing, she did not find success with the pieces she wrote at this time.[1] She did, however, use her money to assist other artists. In 1880, she was obliged to move back to Lübeck at her husband's insistence as their divorce was not finalized.[2]

Boy-Ed spent much of her spare time writing while raising her children, but did not become successful until the age of 30. A book of her novellas about the Hanseatic middle classes was the first of about 70 that she published. Boy-Ed studied and wrote about leading German women like Charlotte von Stein, Charlotte von Kalb and the French writer Germaine de Staël. Like them, she tried to support women's issues in her writings although her principal reason for writing was to make money. She achieved a wide readership for her books, as well as the hundreds of newspaper articles that she wrote.[1] Boy-Ed invested in an impressive apartment and was a patron of the arts.[2]

In September 1914, at the outset of the First World War, Boy-Ed's son Walther was killed in France. Undeterred, Boy-Ed wrote of the need for a mother's sacrifice. She published her ideas in 1915 under the title Soldiers' Mothers in which she makes it clear, "A mother is only dust on the road to victory".[3] Boy-Ed's son, Karl, was the naval attaché of the German Embassy at Washington. His younger brother Emil was also a naval officer.[4] Karl recalled that Thomas Mann was amongst the many literary and musical people who visited his mother's home.[5] Boy-Ed died in 1928 in Travemünde and was buried in Lübeck.[2]

Selected works[edit]

- Ein Tropfen, 1882

- Die Unversuchten, 1886

- Dornenkronen, 1886

- Ich, 1888

- Fanny Förster, 1889

- Nicht im Geleise, 1890

- Ein Kind', 1892

- Empor!, 1892

- Werde zum Weib, 1894

- Sturm, 1894

- Die säende Hand, 1902

- Das ABC des Lebens, 1903

- Heimkehrfieber. Roman aus dem Marineoffiziersleben, 1904

- Die Ketten, 1904

- Der Festungsgarten, 1905

- Ein Echo, 1908

- Nichts über mich!, 1910

- Ein königlicher Kaufmann, Hanseatischer Roman, 1910

- Hardy von Arnbergs Leidensgang, 1911.

- Ein Augenblick im Paradies, 1912

- Charlotte von Kalb. Eine psychologische Studie, 1912

- Eine Frau wie Du! 1913

- Stille Helden, 1914

- Vor der Ehe, 1915

- Die Glücklichen 1916 (?)

- Das Martyrium der Charlotte von Stein. Versuch ihrer Rechtfertigung, 1916

- Die Opferschale, 1916

- Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt..., 1916

- Erschlossene Pforten, 1917

- Um ein Weib, 1920

- Aus Tantalus Geschlecht, 1920

- Glanz, 1920

- Germaine von Stael. Ein Buch anläßlich ihrer..., 1921

- Brosamen, 1922

- Fast ein Adler, 1922

- Annas Ehe, 1923

- Das Eine, 1924

- Die Flucht, ca. 1925

- Gestern und morgen, 1926

- Aus alten und neuen Tagen, 1926

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Wilson, Katharina M., ed. (1991). An encyclopedia of continental women writers. New York u.a.: Garland. p. 160. ISBN 0824085477.

- ^ a b c d Ida Boy-Ed, Sophie.byu.ed, retrieved 11 March 2014

- ^ Siebrecht, Claudia (2013). The aesthetics of loss : German women's art of the First World War (1st ed.). Corby: Oxford University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0191630675.

- ^ "Ida Boy-Ed speaks for German women" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1914. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Feilitzsch, Heribert von (2012). In plain sight : Felix A. Sommerfeld, spymaster in Mexico, 1908 to 1914 (1st ed.). Amissville, Vir.: Henselstone Verlag. p. 409. ISBN 978-0985031701.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alker, Ernst (1955), "Boy-Ed, Ida Cornelia Ernestine", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 2, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, p. 495; (full text online)

- Dreyer, Elsa: Unvergessene Frauen (…) Ida Boy-Ed in Lichtwark Nr. 9, August 1949, Hrsg.: Lichtwark-Ausschuß, Bergedorf. Siehe jetzt: Verlag HB-Werbung, Hamburg-Bergedorf. ISSN 1862-3549

- Mann, Thomas: Briefe an Otto Grautoff (1894–1901) und Ida Boy-Ed (1903–1928), Hrsg.: Peter de Mendelssohn, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1975

- Saxe, Cornelia: Ida Boy-Ed. In: Britta Jürgs (Hg.): Denn da ist nichts mehr, wie es die Natur gewollt. Portraits von Künstlerinnen und Schriftstellerinnen um 1900. AvivA Verlag, Berlin, 2001, ISBN 3-932338-13-8; S.193-215

- Wagner-Zereini, Gabriele: Die Frau am Fenster. Zur Entwicklung einer weiblichen Schreibweise am Beispiel der Lübecker Schriftstellerin Ida Boy-Ed (1852–1928). Dissertation Univ. Frankfurt/M. 1999