Human geography

Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography which studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment, examples of which include urban sprawl and urban redevelopment.[1] It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social interactions and the environment through qualitative and quantitative methods.[2][3]This multidisciplinary approach draws from sociology, anthropology, economics, and environmental science, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the intricate connections that shape lived spaces.[4]

History[edit]

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (October 2022) |

| History of geography |

|---|

|

The Royal Geographical Society was founded in England in 1830.[5] The first professor of geography in the United Kingdom was appointed in 1883,[6] and the first major geographical intellect to emerge in the UK was Halford John Mackinder, appointed professor of geography at the London School of Economics in 1922.[6]

The National Geographic Society was founded in the United States in 1888 and began publication of the National Geographic magazine which became, and continues to be, a great popularizer of geographic information. The society has long supported geographic research and education on geographical topics.

The Association of American Geographers was founded in 1904 and was renamed the American Association of Geographers in 2016 to better reflect the increasingly international character of its membership.

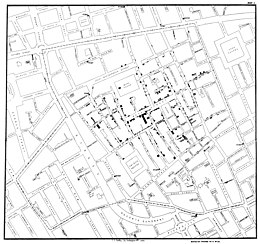

One of the first examples of geographic methods being used for purposes other than to describe and theorize the physical properties of the earth is John Snow's map of the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. Though Snow was primarily a physician and a pioneer of epidemiology rather than a geographer, his map is probably one of the earliest examples of health geography.

The now fairly distinct differences between the subfields of physical and human geography developed at a later date. The connection between both physical and human properties of geography is most apparent in the theory of environmental determinism, made popular in the 19th century by Carl Ritter and others, and has close links to the field of evolutionary biology of the time. Environmental determinism is the theory that people's physical, mental and moral habits are directly due to the influence of their natural environment. However, by the mid-19th century, environmental determinism was under attack for lacking methodological rigor associated with modern science, and later as a means to justify racism and imperialism.

A similar concern with both human and physical aspects is apparent during the later 19th and first half of the 20th centuries focused on regional geography. The goal of regional geography, through something known as regionalisation, was to delineate space into regions and then understand and describe the unique characteristics of each region through both human and physical aspects. With links to possibilism and cultural ecology some of the same notions of causal effect of the environment on society and culture remain with environmental determinism.

By the 1960s, however, the quantitative revolution led to strong criticism of regional geography. Due to a perceived lack of scientific rigor in an overly descriptive nature of the discipline, and a continued separation of geography from its two subfields of physical and human geography and from geology, geographers in the mid-20th century began to apply statistical and mathematical models in order to solve spatial problems.[1] Much of the development during the quantitative revolution is now apparent in the use of geographic information systems; the use of statistics, spatial modeling, and positivist approaches are still important to many branches of human geography. Well-known geographers from this period are Fred K. Schaefer, Waldo Tobler, William Garrison, Peter Haggett, Richard J. Chorley, William Bunge, and Torsten Hägerstrand.

From the 1970s, a number of critiques of the positivism now associated with geography emerged. Known under the term 'critical geography,' these critiques signaled another turning point in the discipline. Behavioral geography emerged for some time as a means to understand how people made perceived spaces and places and made locational decisions. The more influential 'radical geography' emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. It draws heavily on Marxist theory and techniques and is associated with geographers such as David Harvey and Richard Peet. Radical geographers seek to say meaningful things about problems recognized through quantitative methods,[7] provide explanations rather than descriptions, put forward alternatives and solutions, and be politically engaged,[8] rather than using the detachment associated with positivists. (The detachment and objectivity of the quantitative revolution was itself critiqued by radical geographers as being a tool of capital). Radical geography and the links to Marxism and related theories remain an important part of contemporary human geography (See: Antipode). Critical geography also saw the introduction of 'humanistic geography', associated with the work of Yi-Fu Tuan, which pushed for a much more qualitative approach in methodology.

The changes under critical geography have led to contemporary approaches in the discipline such as feminist geography, new cultural geography, settlement geography, "demonic" geographies, and the engagement with postmodern and post-structural theories and philosophies.

Fields[edit]

The primary fields of study in human geography focus on the core fields of:

Cultures[edit]

Cultural geography is the study of cultural products and norms - their variation across spaces and places, as well as their relations. It focuses on describing and analyzing the ways language, religion, economy, government, and other cultural phenomena vary or remain constant from one place to another and on explaining how humans function spatially.[9]

- Subfields include: Social geography, Animal geographies, Language geography, Sexuality and space, Children's geographies, and Religion and geography.

Development[edit]

Development geography is the study of the Earth's geography with reference to the standard of living and the quality of life of its human inhabitants, study of the location, distribution and spatial organization of economic activities, across the Earth. The subject matter investigated is strongly influenced by the researcher's methodological approach.

Economies[edit]

Economic geography examines relationships between human economic systems, states, and other factors, and the biophysical environment.

- Subfields include: Marketing geography and Transportation geography

Health[edit]

Medical or health geography is the application of geographical information, perspectives, and methods to the study of health, disease, and health care. Health geography deals with the spatial relations and patterns between people and the environment. This is a sub-discipline of human geography, researching how and why diseases are spread and contained.[10]

Histories[edit]

Historical geography is the study of the human, physical, fictional, theoretical, and "real" geographies of the past. Historical geography studies a wide variety of issues and topics. A common theme is the study of the geographies of the past and how a place or region changes through time. Many historical geographers study geographical patterns through time, including how people have interacted with their environment, and created the cultural landscape.

Politics[edit]

Political geography is concerned with the study of both the spatially uneven outcomes of political processes and the ways in which political processes are themselves affected by spatial structures.

- Subfields include: Electoral geography, Geopolitics, Strategic geography and Military geography

Population[edit]

Population geography is the study of ways in which spatial variations in the distribution, composition, migration, and growth of populations are related to their environment or location.

Settlement[edit]

Settlement geography, including urban geography, is the study of urban and rural areas with specific regards to spatial, relational and theoretical aspects of settlement. That is the study of areas which have a concentration of buildings and infrastructure. These are areas where the majority of economic activities are in the secondary sector and tertiary sectors.

Urbanism[edit]

Urban geography is the study of cities, towns, and other areas of relatively dense settlement. Two main interests are site (how a settlement is positioned relative to the physical environment) and situation (how a settlement is positioned relative to other settlements). Another area of interest is the internal organization of urban areas with regard to different demographic groups and the layout of infrastructure. This subdiscipline also draws on ideas from other branches of Human Geography to see their involvement in the processes and patterns evident in an urban area.[11][12]

- Subfields include: Economic geography, Population geography, and Settlement geography. These are clearly not the only subfields that could be used to assist in the study of Urban geography, but they are some major players.[11]

Philosophical and theoretical approaches[edit]

Within each of the subfields, various philosophical approaches can be used in research; therefore, an urban geographer could be a Feminist or Marxist geographer, etc.

Such approaches are:

List of notable human geographers[edit]

Journals[edit]

As with all social sciences, human geographers publish research and other written work in a variety of academic journals. Whilst human geography is interdisciplinary, there are a number of journals that focus on human geography.

These include:

- ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies[13]

- Antipode

- Area

- Dialogues in Human Geography

- Economic geography

- Environment and Planning

- Geoforum

- Geografiska Annaler

- GeoHumanities[14]

- Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions[15]

- Human Geography

- Migration Letters

- Progress in Human Geography

- Southeastern Geographer[16]

- Social & Cultural Geography[17]

- Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie

- Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers

See also[edit]

- AP Human Geography

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Emotional geography

- Geography of food

- Integrated geography

- Physical geography

- Political ecology

- Technical geography

References[edit]

- ^ a b Johnston, Ron (2000). "Human Geography". In Johnston, Ron; Gregory, Derek; Pratt, Geraldine; et al. (eds.). The Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 353–360.

- ^ Russel, Polly. "Human Geography". British Library. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Reinhold, Dennie (7 February 2017). "Human Geography". www.geog.uni-heidelberg.de. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Rubenstein, James M. (2020). Cultural Landscape, The: An Introduction to Human Geography (13th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 9780135729625.

- ^ Royal Geographical Society. "History". Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Chairs of Geography in British Universities". Geography. 46 (4): 349–353. 1961. ISSN 0016-7487. JSTOR 40565547.

- ^ Harvey, David (1973). Social Justice and the City. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 128–129.

- ^ Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography (2009). "Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography: Celebrating Over 40 years of Radical Geography 1969-2009". Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G.; Domosh, Mona; Rowntree, Lester (1994). The human mosaic: a thematic introduction to cultural geography. New York: HarperCollinsCollegePublishers. ISBN 978-0-06-500731-2.

- ^ Dummer, Trevor J.B. (22 April 2008). "Health geography: supporting public health policy and planning". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 178 (9): 1177–1180. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071783. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 2292766. PMID 18427094.

- ^ a b Palm, Risa (1982). "Urban geography: city structures". Progress in Geography. 6: 89–95. doi:10.1177/030913258200600104. S2CID 157288359.

- ^ Kaplan, Dave H.; Holloway, Steven; Wheeler, James O. (2014). Urban Geography, 3rd. Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-57385-3.

- ^ ACME journal homepage. Archived 6 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Accessed: 18 May 2015.

- ^ "GeoHumanities". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ "Global Environmental Change". Retrieved 11 May 2020 – via www.journals.elsevier.com.

- ^ Project MUSE journal 279

- ^ "Social & Cultural Geography". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

Further reading[edit]

- Clifford, N.J.; S.L.; Rice, S.P.; Valentine, G., eds. (2009). Key Concepts in Geography (2nd ed.). London: SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-3021-5.

- Peet, Richard, ed. (1998). Modern Geographical Thought. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-378-2.

- Cloke, Paul J.; Crang, Phil; Crang, Philip; Goodwin, Mark (2005). Introducing human geographies (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-88276-4.

- Cloke, Paul J.; Crang, Philip; Goodwin, Mark (2004). Envisioning human geographies. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-72013-4.

- Crang, Mike; Thrift, Nigel J. (2000). Thinking space. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16016-2.

- Daniels, Peter; Bradshaw, Michael; Shaw, Denis J.B.; Sidaway, James D. (2004). An Introduction to Human Geography: issues for the 21st century (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-121766-9.

- de Blij, Harm; Jan, De (2008). Geography: realms, regions, and concepts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-12905-0.

- Flowerdew, Robin; Martin, David (2005). Methods in human geography: a guide for students doing a research project (2nd ed.). Harlow: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-582-47321-8.

- Gregory, Derek; Martin, Ron G.; Smith, Graham (1994). Human geography: society, space and social science. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-45251-6.

- Harvey, David D. (1996). Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-55786-680-6.

- Johnston, R.J. (1979). Geography and Geographers. Anglo-American Human Geography since 1945. Edward Arnold, London.

- Johnston, R.J. (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography (5th ed.). Blackwell Publishers, London.

- Johnston, R.J (2002). Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World. Blackwell Publishers, London.

- Moseley, William W.; Lanegran, David A.; Pandit, Kavita (2007). The Introductory Reader in Human Geography: Contemporary Debates and Classic Writings. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4051-4922-8.

- Soja, Edward W. (1989). Postmodern geographies : the reassertion of space in critical social theory. London: Verso. ISBN 0-86091-225-6. OCLC 18190662.

External links[edit]

Media related to Human geography at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Human geography at Wikimedia Commons- Worldmapper – Mapping project using social data sets