Holostei

| Holostei Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Spotted gar, Lepisosteus oculatus | |

| |

| Bowfin, Amia calva | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Subclass: | Neopterygii |

| Infraclass: | Holostei Müller, 1846 |

| Clades (with orders) | |

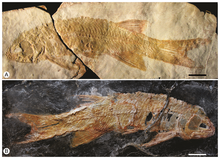

Holostei is a group of ray-finned bony fish. It is divided into two major clades, the Halecomorphi, represented by the single living genus, Amia with two species, the bowfins (Amia calva and Amia ocellicauda), as well as the Ginglymodi, the sole living representatives being the gars (Lepisosteidae), represented by seven living species in two genera (Atractosteus, Lepisosteus).[3] The earliest members of the clade, which are putative "semionotiforms" such as Acentrophorus and Archaeolepidotus, are known from the Middle to Late Permian and are among the earliest known neopterygians.[4][5][1][2]

Holostei was thought to be regarded as paraphyletic. However, a recent study provided evidence that the Holostei are the closest living relates of the Teleostei, both within the Neopterygii. This was found from the morphology of the Holostei, for example presence of a paired vomer.[6] Holosteans are closer to teleosts than are the chondrosteans, the other group intermediate between teleosts and cartilaginous fish, which are regarded as (at the nearest[a]) a sister group to the Neopterigii.

The spiracles of holosteans are reduced to vestigial remnants and the bones are lightly ossified. The thick ganoid scales of the gars are more primitive than those of the bowfin.

Characteristics[edit]

Holosteans share with other non-teleost ray-finned fish a mixture of characteristics of teleosts and sharks. In comparison with the other group of non-teleost ray-finned fish, the chondrosteans, the holosteans are closer to the teleosts and further from sharks: the pair of spiracles found in sharks and chondrosteans is reduced in holosteans to a remnant structure: in gars, the spiracles do not even open to the outside;[7] the skeleton is lightly ossified: a thin layer of bone covers a mostly cartilaginous skeleton in the bowfins. In gars, the tail is still heterocercal but less so than in the chondrosteans. Bowfins have many-rayed dorsal fins and can breathe air like the bichirs.

In the holosteans a primary pulmonoid (respiratory) swim bladder is still present, a trait that was independently lost in both chondrostei and teleostei, the only other two lineages of fish with a swim bladder (in some teleosts the swim bladder have since evolved to become secondarily respiratory again).[8]

The gars have thick ganoid scales typical of sturgeons whereas the bowfin has thin bony scales like the teleosts. The gars are therefore in this regard considered more primitive than the bowfin.[9]

The name Holostei derives from the Greek words holos, meaning whole, and osteon, meaning bone: a reference to their bony skeletons.

Systematics of Neopterygii[edit]

The evolutionary relationships of gars, bowfin and teleosts were a matter of debate. There are two competing hypotheses on the systematics of neopterygians:

Halecostomi hypothesis[edit]

The Halecostomi hypothesis proposes Halecomorphi (bowfin and its fossil relatives) as the sister group of Teleostei, the major group of living neopterygians, rendering the Holostei paraphyletic.[10]

Holostei hypothesis[edit]

The Holostei hypothesis, where the gars and bowfin form the clade Holostei as the sister group to Teleostei, is better supported than the Halecostomi hypothesis, rendering the latter paraphyletic.[11][12][13][14] It proposes Halecomorphi as the sister group of Ginglymodi, the group which includes living gars (Lepisosteiformes) and their fossil relatives.[15][16][3] It is estimated that the last common ancestor of gars and bowfin lived at least 250 million years ago.[17]

| Neopterygii |

| ||||||

Ginglymodi comprises three orders: Lepisosteiformes, Semionotiformes and Kyphosichthyiformes. Lepisosteiformes includes 1 family, 2 genera, and 7 species that are commonly referred to as gars. Semionotiformes and Kyphosichthyiformes are extinct orders.

Halecomorphi contains the orders Parasemionotiformes, Panxianichthyiformes, Ionoscopiformes, and Amiiformes. In addition to many extinct species, Amiiformes includes only 1 extant species that is commonly referred to as the bowfin. Parasemionotiformes, Panxianichthyiformes, and Ionoscopiformes have no living members.

Gars and bowfins are found in North America and in freshwater ecosystems. The differences in each can be spotted very easily from just looking at the fishes. The gars have elongated jaws with fanlike teeth, only 3 branchiostegal rays, and a small dorsal fin. Meanwhile the bowfins have a terminal mouth, 10–13 flattened branchiostegal rays, and a long dorsal fin.

Phylogeny of bony fishes[edit]

The cladogram shows the relationships of holosteans to other living groups of bony fish (Osteichthyes), the great majority of which are teleosts,[19] and to the terrestrial vertebrates (tetrapods) that evolved from a related group of lobe-finned fish.[20][21] Approximate dates are from Near et al. (2012).[19]

| Euteleostomi/ |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Osteichthyes |

Notes[edit]

- ^ Depending who you ask, the Chondrostei may be paraphyletic, or the Polypteridae may be considered not part of them.

- ^ Thus the former "Chondrostei" is not a clade, but is broken up. See Actinopteri for a possible reclassification.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Broughton, Richard E.; Betancur-R., Ricardo; Li, Chenhong; Arratia, Gloria; Ortí, Guillermo (2013-04-16). "Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis reveals the pattern and tempo of bony fish evolution". PLOS Currents. 5: ecurrents.tol.2ca8041495ffafd0c92756e75247483e. doi:10.1371/currents.tol.2ca8041495ffafd0c92756e75247483e (inactive 2024-02-27). ISSN 2157-3999. PMC 3682800. PMID 23788273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) - ^ a b "PBDB". paleobiodb.org. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ a b López-Arbarello, Adriana; Sferco, Emilia (March 2018). "Neopterygian phylogeny: the merger assay". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (3): 172337. Bibcode:2018RSOS....572337L. doi:10.1098/rsos.172337. PMC 5882744. PMID 29657820.

- ^ Romano, Carlo (2021). "A Hiatus Obscures the Early Evolution of Modern Lineages of Bony Fishes" (PDF). Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 672. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.618853. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ Brinkmann, W.; Romano, C.; Bucher, H.; Ware, D.; Jenks, J. (2010). "Palaeobiogeography and stratigraphy of advanced Gnathostomian fishes (Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes) in the Early Triassic and from selected Anisian localities (report 1863-2009): Literaturbericht". Zentralblatt für Geologie und Paläontologie. Teil 2. 2009 (5/6): 765–812. doi:10.5167/uzh-34071. ISSN 0044-4189.

- ^ Hastings, Walker Jr., Galland (2014). FISHES, A GUIDE TO THEIR DIVERSITY. Oakland, California: University of California Press. pp. 60–62.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ontario. Game and fish commission

- ^ Respiratory Biology of Animals: evolutionary and functional morphology

- ^ Rick Leah. "Holostei". University of Liverpool (http://www.liv.ac.uk).

- ^ Patterson C. Interrelationships of holosteans. In: Greenwood P H, Miles R S, Patterson C, eds. Interrelationships of Fishes. Zool J Linn Soc, 1973, 53(Suppl): 233–305

- ^ Betancur-R (2016). "Phylogenetic Classification of Bony Fishes Version 4". Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- ^ Nelson, Joseph, S. (2016). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Actinopterygii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 3 April 2006.

- ^ R. Froese and D. Pauly, ed. (February 2006). "FishBase".

- ^ Olsen P. E. (1984). "The skull and pectoral girdle of the parasemionotid fish Watsonulus eugnathoides from the Early Triassic Sakemena Group of Madagascar with comments on the relationships of the holostean fishes". J Vertebr Paleontol. 4 (3): 481–499. Bibcode:1984JVPal...4..481O. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.2050. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10012024.

- ^ Grande, Lance; Bemis, William E. (1998). "A Comprehensive Phylogenetic Study of Amiid Fishes (Amiidae) Based on Comparative Skeletal Anatomy. an Empirical Search for Interconnected Patterns of Natural History". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (sup001): 1–696. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18S...1G. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011114.

- ^ The bowfin genome illuminates the developmental evolution of ray-finned fishes

- ^ Brito, Paulo M.; Alvarado-Ortega, Jesus (2013). "Cipactlichthys scutatus, gen. nov., sp. nov. a New Halecomorph (Neopterygii, Holostei) from the Lower Cretaceous Tlayua Formation of Mexico". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e73551. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873551B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073551. PMC 3762789. PMID 24023885.

- ^ a b Thomas J. Near; et al. (2012). "Resolution of ray-finned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification". PNAS. 109 (34): 13698–13703. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10913698N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206625109. PMC 3427055. PMID 22869754.

- ^ Betancur-R, Ricardo; et al. (2013). "The Tree of Life and a New Classification of Bony Fishes". PLOS Currents Tree of Life. 5 (Edition 1). doi:10.1371/currents.tol.53ba26640df0ccaee75bb165c8c26288. hdl:2027.42/150563. PMC 3644299. PMID 23653398.

- ^ Laurin, M.; Reisz, R.R. (1995). "A reevaluation of early amniote phylogeny". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (2): 165–223. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1995.tb00932.x.