History of spaceflight

| Part of a series on |

| Spaceflight |

|---|

|

|

|

Spaceflight began in the 20th century following theoretical and practical breakthroughs by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Robert H. Goddard, and Hermann Oberth, each of whom published works proposing rockets as the means for spaceflight.[a] The first successful large-scale rocket programs were initiated in Nazi Germany by Wernher von Braun. The Soviet Union took the lead in the post-war Space Race, launching the first satellite,[1] the first animal,[2]: 155 the first human[3] and the first woman[4] into orbit. The United States would then land the first men on the Moon in 1969. Through the late 20th century, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and China were also working on projects to reach space.

Following the end of the Space Race, spaceflight has been characterized by greater international cooperation, cheaper access to low Earth orbit and an expansion of commercial ventures. Interplanetary probes have visited all of the planets in the Solar System, and humans have remained in orbit for long periods aboard space stations such as Mir and the ISS. Most recently, China has emerged as the third nation with the capability to launch independent crewed missions, whilst operators in the commercial sector have developed reusable booster systems and craft launched from airborne platforms.In 2020, SpaceX became the first commercial operator to successfully launch a crewed mission to the International Space Station with Crew Dragon Demo-2, whose name varies depending on the organization.

Background[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a burst of scientific investigation into interplanetary travel, inspired by fiction by writers such as Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon, Around the Moon) and H.G. Wells (The First Men in the Moon, The War of the Worlds).[citation needed]

The first realistic proposal for spaceflight was "Issledovanie Mirovikh Prostranstv Reaktivnimi Priborami", or "The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices" by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, published in 1903.[6]

Spaceflight became an engineering possibility with the work of Robert H. Goddard's publication in 1919 of his paper "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes", where his application of the de Laval nozzle to liquid fuel rockets gave sufficient power for interplanetary travel to become possible. This paper was highly influential on Hermann Oberth and Wernher Von Braun, later key players in spaceflight.[citation needed]

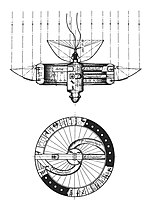

In 1929, the Slovene officer Hermann Noordung was the first to imagine a complete space station in his book The Problem of Space Travel.[7][8]

The first rocket to reach space was a German V-2 rocket, on a vertical test flight in June 1944.[9] After the war ended, the research and development branch of the (British) Ordinance Office organised Operation Backfire which, in October 1945, assembled enough V-2 missiles and supporting components to enable the launch of three (possibly four, depending on source consulted) of them from a site near Cuxhaven in northern Germany. Although these launches were inclined and the rockets did not achieve the altitude necessary to be regarded as sub-orbital spaceflight, the Backfire report remains the most extensive technical documentation of the rocket, including all support procedures, tailored vehicles and fuel composition.[10]

Subsequently, the British Interplanetary Society proposed an enlarged man-carrying version of the V-2 called Megaroc. The plan, written in 1946, envisaged a three-year development programme culminating in the launch of test pilot Eric Brown on a sub-orbital mission in 1949.[11][12]

The decision by the Ministry of Supply under Attlee's government to concentrate on research into nuclear power generation and sub-sonic passenger jet aircraft over supersonic atmospheric flight and spaceflight delayed the introduction of both of the latter, although only by a year in the case of supersonic flight, as the data from the Miles M.52 was handed to Bell Aircraft.[citation needed]

In 1947, the US sent the first animals in space, fruit flies, although not into orbit, through a V-2 rocket launched from White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico.[13][14][15] On June 14, 1949, the US launched the first mammal into space, a rhesus macaque monkey named Albert II, on a sub-orbital flight.[citation needed]

Space Race (1957 to 1970s)[edit]

First artificial satellite[edit]

The race began in 1957 when both the US and the USSR made statements announced they planned to launch artificial satellites during the 18-month long International Geophysical Year of July 1957 to December 1958. On July 29, 1957, the US announced a planned launch of the Vanguard by the spring of 1958, and on July 31, the USSR announced it would launch a satellite in the fall of 1957.[citation needed]

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite of Earth in the history of humankind.

On November 3, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the second satellite, Sputnik 2, and the first to carry a living animal into orbit, a dog named Laika. Sputnik 3 was launched on May 15, 1958, and carried a large array of instruments for geophysical research and provided data on pressure and composition of the upper atmosphere, concentration of charged particles, photons in cosmic rays, heavy nuclei in cosmic rays, magnetic and electrostatic fields, and meteoric particles. After a series of failures with the program, the US succeeded with Explorer 1, which became the first US satellite in space, on February 1, 1958. This carried scientific instrumentation and detected the theorized Van Allen radiation belt. The US public shock over Sputnik 1 became known as the Sputnik crisis. On July 29, 1958, the US Congress passed legislation turning the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with responsibility for the nation's civilian space programs. In 1959, NASA began Project Mercury to launch single-man capsules into Earth orbit and chose a corps of seven astronauts introduced as the Mercury Seven.[citation needed]

First man in space[edit]

On April 12, 1961, the USSR opened the era of crewed spaceflight, with the flight of the first cosmonaut (Russian name for space travelers), Yuri Gagarin. Gagarin's flight, part of the Soviet Vostok space exploration program, took 108 minutes and consisted of a single orbit of the Earth.[citation needed]

On August 7, 1961, Gherman Titov, another Soviet cosmonaut, became the second man in orbit during his Vostok 2 mission. Titov orbited Earth 17 times in over 25 hours during his spaceflight.[16]

By June 16, 1963, the Union launched a total of six Vostok cosmonauts, two pairs of them flying concurrently, and accumulating a total of 260 cosmonaut-orbits and just over sixteen cosmonaut-days in space.[citation needed]

On May 5, 1961, the US launched its first suborbital Mercury astronaut, Alan Shepard, in the Freedom 7 capsule. Prior to that on January 31, through NASA's Mercury-Redstone 2 mission, the chimpanzee Ham became the first Hominidae in space.[17][18][19]

First woman in space[edit]

The first woman in space was former civilian parachutist Valentina Tereshkova, who entered orbit on June 16, 1963, aboard the Soviet mission Vostok 6. The chief Soviet spacecraft designer, Sergey Korolyov, conceived of the idea to recruit a female cosmonaut corps and launch two women concurrently on Vostok 5/6. However, his plan was changed to launch a male first in Vostok 5, followed shortly afterward by Tereshkova. The then first secretary of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, spoke to Tereshkova by radio during her flight.[20]

On November 3, 1963, Tereshkova married fellow cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev, who had previously flown on Vostok 3.[21] On June 8, 1964, she gave birth to the first child conceived by two space travelers.[22] The couple divorced in 1982, and Tereshkova went on to become a prominent member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

The second woman to fly to space was aviator Svetlana Savitskaya, aboard Soyuz T-7 on August 18, 1982.[23]

Competition develops[edit]

Khrushchev pressured Korolyov to quickly produce greater space achievements in competition with the announced Gemini and Apollo plans. Rather than allowing him to develop his plans for a crewed Soyuz spacecraft, he was forced to make modifications to squeeze two or three men into the Vostok capsule, calling the result Voskhod. Only two of these were launched. Voskhod 1 was the first spacecraft with a crew of three, who could not wear space suits because of size and weight constrictions. Alexei Leonov made the first spacewalk when he left the Voskhod 2 on March 8, 1965. He was almost lost in space when he had extreme difficulty fitting his inflated space suit back into the cabin through an airlock, and a landing error forced him and Voskhod 2 crewmate Pavel Belyayev to be lost in dense woods for hours before being found by the recovery crew and rescued days later.[citation needed]

The start of crewed Gemini missions was delayed a year later than NASA had planned, but ten largely successful missions were launched in 1965 and 1966, allowing the US to overtake the Soviet lead by achieving space rendezvous (Gemini 6A) and docking (Gemini 8) of two vehicles, long duration flights of eight days (Gemini 5) and fourteen days (Gemini 7), and demonstrating the use of extra-vehicular activity to do useful work outside a spacecraft (Gemini 12).[citation needed]

The USSR made no crewed flights during this period but continued to develop its Soyuz craft and secretly accepted Kennedy's implicit lunar challenge, designing Soyuz variants for lunar orbit and landing. They also attempted to develop the N1, a large, crewed Moon-capable launch vehicle similar to the US Saturn V.[citation needed]

As both nations rushed to get their new spacecraft flying with men, the intensity of the competition caught up to them in early 1967, when they suffered their first crew fatalities. On January 27, the entire crew of Apollo 1, "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, were killed by suffocation in a fire that swept through their cabin during a ground test approximately one month before their planned launch. On April 24, the single pilot of Soyuz 1, Vladimir Komarov, was killed in a crash when his landing parachutes tangled, after a mission cut short by electrical and control system problems. Both accidents were determined to be caused by design defects in the spacecraft, which were corrected before crewed flights resumed.[citation needed]

The US conducted the first crewed spaceflight to leave Earth orbit and orbit the Moon on December 21, 1968, with the Apollo 8 space mission. Later they succeeded in achieving President Kennedy's goal on July 20, 1969, with the landing of Apollo 11. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to set foot on the Moon. Six such successful landings were achieved through 1972, with one failure on Apollo 13.[citation needed]

The N1 rocket suffered four catastrophic uncrewed launch failures between 1969 and 1972, and the Soviet government officially discontinued its crewed lunar program on June 24, 1974, when Valentin Glushko succeeded Korolyov as General Spacecraft Designer.[24]

Later phase[edit]

Both nations went on to fly relatively small, non-permanent crewed space laboratories Salyut and Skylab, using their Soyuz and Apollo craft as shuttles. The US launched only one Skylab, but the USSR launched a total of seven "Salyuts", three of which were secretly Almaz military crewed reconnaissance stations, which carried "defensive" cannons. Crewed reconnaissance stations were found to be a bad idea since uncrewed satellites could do the job much more cost-effectively. The United States Air Force had planned a crewed reconnaissance station, the Manned Orbital Laboratory, which was cancelled in 1969. The Soviets cancelled Almaz in 1978.[citation needed]

In a season of detente, the two competitors declared an end to the race and literally shook hands on July 17, 1975, with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, where the two craft docked, and the crews exchanged visits.

Diversification and development stagnation (1970s to 2010s)[edit]

While participation of private actors and other countries beside the Soviet Union and the United States in spaceflight had been the case from the very start of spaceflight development. A first commercial satellite had been launched by 1962, as well as in 1965 a third country achieving orbital spaceflight. The very beginning of the space age, the launch of Sputnik was in the context of international exchange, the International Geophysical Year 1957. Also soon into the space age the international community came together starting to negotiate dedicated international law governing outer space activity.

In the 1970s the Soviet Union started to invite other countries to fly their people into space through its Intercosmos program and the United States started to include women and people of colour in its astronaut program.

First exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union was formalized in the 1962 Dryden-Blagonravov agreement, calling for cooperation on the exchange of data from weather satellites, a study of the Earth's magnetic field, and joint tracking of the NASA Echo II balloon satellite.[26] In 1963 President Kennedy could even interest premier Khrushchev in a joint crewed Moon landing,[27][28] but after the assassination of Kennedy in November 1963 and Khrushchev's removal from office in October 1964, the competition between the two nations' crewed space programs heated up, and talk of cooperation became less common, due to tense relations and military implications. Only later the United States and the Soviet Union slowly started to exchange more information and engage in joint programs, particularly in the light of the development of safety standards since 1970,[29] producing the co-developed APAS-75 and later docking standards. Most notably this signaled the ending of the first era of the space age, the Space Race, through the Apollo-Soyuz mission which became the basis for the Shuttle-Mir program and eventually the International Space Station programme.

Such international cooperation, and international spaceflight organization like most notably the European Space Agency, fueled by increasingly more countries achieving spaceflight capabilies and together with a since the 1980s established private spaceflight sector, allowed the formation of an international and commercial post-Space Race spaceflight economy and period, producing many individual firsts as well as space exploration discoveries, until competition started to rise again from the 2010s and by the early 2020s.

Private spaceflight and cost reduction (2010s to present)[edit]

Starting in the 2010s the diversified spaceflight sector had become by the 2020s increasingly competitive with returning inter-national competition and cooperation barrieres, like a cooperation ban enacted in the United States on China in 2011 and later the European Space Agency banning Russia,[30] and increased private competition in spaceflight capabilities, enabled by the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015.

Some have called it a New Space Race period,[31] particularly in light of China's speedy advances and other Asian countries competing in advancing their spaceflight achievements, creating an Asian Space Race.[32] Though international cooperation and international private spaceflight remains an integral part of the sector, but competitively diversifying commercial international contracting, such as international private human spaceflight of e.g. Axiom Space in cooperation with different countries and heavily relying on the International Space Station. Which also continued operation despite international confrontations like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, while private spaceflight, with Space-X's Starlink, became a significant element in the war and international politics.

Meanwhile, a range of new lunar spaceflight programs are being advanced especially as international programs, from the Artemis program and the China-Russian plans to establish a lunar base, to the European Space Agency pened Moon Village.

This competitive but international commercial development of the spaceflight sector has been called New Space.[33]

By programs[edit]

| Orbital human spaceflight (beyond Kármán line) | |||

| Program | Years | Flights | First Crewed Flight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vostok | 1961–1963 | 6 | Vostok 1 |

| Mercury | 1962–1963 | 4[b] | Mercury-Atlas 6 |

| Voskhod | 1964–1965 | 2 | Voskhod 1 |

| Gemini | 1965–1966 | 10 | Gemini 3 |

| Soyuz | 1967–present | 141[c] | Soyuz 1 |

| Apollo | 1968–1972 | 11[d] | Apollo 7 |

| Skylab | 1973–1974 | 3 | Skylab 2 |

| Apollo-Soyuz | 1975 | 1[e] | Apollo-Soyuz |

| Space Shuttle | 1981–2011 | 135[f] | STS-1 |

| Shenzhou | 2003–present | 6 | Shenzhou 5 |

| Crew Dragon | 2020–present | 11 | Demo-2 |

| Suborbital human spaceflight | |||

| Program | Year | Flights | |

| Mercury | 1961 | 2 | Mercury 3 |

| X-15 | 1963 | 2 | Flight 90 |

| Soyuz 18a | 1975 | 1 | Soyuz 18a |

| SpaceShipOne | 2004 | 3 | Flight 15P |

| SpaceShipTwo | 2018–present | 3 | VP03 |

United States[edit]

Until the 21st century, space programs of the United States were exclusively operated by government agencies. In the 21st century, several aerospace companies began efforts at developing a private space industry, with SpaceX being the most successful so far.[citation needed]

NASA[edit]

Project Mercury[edit]

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. Its goal was to put a person into Earth orbit and return them safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth on February 20, 1962, aboard the Mercury-Atlas 6.[37]

Project Gemini[edit]

Project Gemini was NASA's second human spaceflight program. The program ran from 1961 to 1966. The program pioneered the orbital maneuvers required for space rendezvous.[38] Ed White became the first American to make an extravehicular activity (EVA, or "space walk"), on June 3, 1965, during Gemini 4.[39] Gemini 6A and 7 accomplished the first space rendezvous on December 15, 1965.[40] Gemini 8 achieved the first space docking with an uncrewed Agena Target Vehicle on March 16, 1966. Gemini 8 was also the first US spacecraft to experience in-space critical failure endangering the lives of the crew.[41]

Apollo program[edit]

The Apollo program was the third human spaceflight program carried out by NASA. The program's goal was to orbit and land crewed vehicles on the Moon.[42] The program ran from 1969 to 1972. Apollo 8 was the first human spaceflight to leave Earth orbit and orbit the Moon on December 21, 1968.[43] Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to set foot on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969.[44]

Skylab[edit]

The Skylab program's goal was to create the first space station of NASA. The program marked the last launch of the Saturn V rocket on May 14, 1973. Many experiments were performed on board, including unprecedented solar studies.[45] The longest crewed mission of the program was Skylab 4 which lasted 84 days, from November 16, 1973, to February 8, 1974.[46] The total mission duration was 2249 days, with Skylab finally falling from orbit over Australia on July 11, 1979.[47]

Space Shuttle[edit]

Although its pace slowed, space exploration continued after the end of the Space Race. The United States launched the first reusable spacecraft, the Space Shuttle, on the 20th anniversary of Gagarin's flight, April 12, 1981. On November 15, 1988, the Soviet Union duplicated this with an uncrewed flight of the only Buran-class shuttle to fly, its first and only reusable spacecraft. It was never used again after the first flight; instead, the Soviet Union continued to develop space stations using the Soyuz craft as the crew shuttle.[citation needed]

Sally Ride became the first American woman in space in 1983. Eileen Collins was the first female Shuttle pilot, and with Shuttle mission STS-93 in July 1999 she became the first woman to command a US spacecraft.The United States continued missions to the ISS and other goals with the high-cost Shuttle system, which was retired in 2011.[citation needed]

Soviet Union[edit]

Sputnik[edit]

The Sputnik 1 became the first artificial Earth satellite on 4 October 1957. The satellite transmitted a radio signal, but had no sensors otherwise.[50] Studying the Sputnik 1 allowed scientists to calculate the drag from the upper atmosphere by measuring position and speed of the satellite.[51] Sputnik 1 broadcast for 21 days until its batteries depleted on 4 October 1957, and the satellite finally fell from orbit on 4 January 1958.[52]

Luna programme[edit]

The Luna programme was a series of uncrewed robotic satellite launches with the goal of studying the Moon. The program ran from 1959 to 1976 and consisted of 15 successful missions, the program achieved many first achievements and collected data on the Moon's chemical composition, gravity, temperature, and radiation. Luna 2 became the first human-made object to make contact with the Moon's surface in September 1959.[53] Luna 3 returned the first photographs of the far side of the Moon in October 1959.[54]

Vostok[edit]

The Vostok Programme was the first Soviet spaceflight project to put Soviet citizens into low Earth orbit and return them safely. The programme carried out six crewed spaceflights between 1961 and 1963. The program was the first program to put humans into space, with Yuri Gagarin becoming the first man in space on April 12, 1961, aboard the Vostok 1.[55] Gherman Titov became the first person to stay in orbit for a full day on August 7, 1961, aboard the Vostok 2.[56] Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space on June 16, 1963, aboard the Vostok 6.[57]

Voskhod[edit]

The Voskhod programme began in 1964 and consisted of two crewed flights before the program was canceled by the Soyuz programme in 1966. Voskhod 1 launched on October 12, 1964, and was the first crewed spaceflight with a multi-crewed vehicle.[58] Alexei Leonov performed the first spacewalk aboard Voskhod 2 on March 18, 1965.[59]

Salyut[edit]

The Salyut programme was the first space station program undertaken by the Soviet Union.[60] The goal was to carry out long-term research into the problems of living in space and a variety of astronomical, biological and Earth-resources experiments. The program ran from 1971 to 1986. Salyut 1, the first station in the program, became the world's first crewed space station.[61]

Soyuz programme[edit]

The Soyuz programme was initiated by the soviet space program in the 1960s and continues as the responsibility of roscosmos to this day. The program currently consists of 140 completed flights, and since the retirement of the US Space Shuttle has been the only craft to transport humans. The program's original goal was part of a program to put a cosmonaut on the Moon and later became crucial to the construction of the Mir space station.[citation needed]

Mir[edit]

Mir (Russian: Мир, IPA: [ˈmʲir]; lit. 'peace' or 'world') was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. Mir was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to 1996. It had a greater mass than any previous spacecraft. At the time it was the largest artificial satellite in orbit, succeeded by the International Space Station (ISS) after Mir's orbit decayed. The station served as a microgravity research laboratory in which crews conducted experiments in biology, human biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology, and spacecraft systems with a goal of developing technologies required for permanent occupation of space.

Mir was the first continuously inhabited long-term research station in orbit and held the record for the longest continuous human presence in space at 3,644 days, until it was surpassed by the ISS on 23 October 2010.[62] It holds the record for the longest single human spaceflight, with Valeri Polyakov spending 437 days and 18 hours on the station between 1994 and 1995. Mir was occupied for a total of twelve and a half years out of its fifteen-year lifespan, having the capacity to support a resident crew of three, or larger crews for short visits.Buran[edit]

International Space Station[edit]

Recent space exploration has proceeded, to some extent in worldwide cooperation, the high point of which was the construction and operation of the International Space Station (ISS). At the same time, the international space race between smaller space powers since the end of the 20th century can be considered the foundation and expansion of markets of commercial rocket launches and space tourism.[citation needed]

The United States continued other space exploration, including major participation with the ISS with its own modules. It also planned a set of uncrewed Mars probes, military satellites, and more. The Constellation program, began by President George W. Bush in 2005, aimed to launch the Orion spacecraft by 2018. A subsequent return to the Moon by 2020 was to be followed by crewed flights to Mars, but the program was canceled in 2010 in favor of encouraging commercial US human launch capabilities.[citation needed]

Russia, a successor to the Soviet Union, has high potential but smaller funding. Its own space programs, some of a military nature, perform several functions. They offer a wide commercial launch service while continuing to support the ISS with several of their own modules. They also operate crewed and cargo spacecraft which continued after the US Shuttle program ended. They are developing a new multi-function Orel spacecraft for use in 2020 and have plans to perform human Moon missions as well.[citation needed]

European Space Agency[edit]

The European Space Agency has taken the lead in commercial uncrewed launches since the introduction of the Ariane 4 in 1988 but is in competition with NASA, Russia, Sea Launch (private), China, India, and others. The ESA-designed crewed shuttle Hermes and space station Columbus were under development in the late 1980s in Europe; however, these projects were canceled, and Europe did not become the third major "space power".[citation needed]

The European Space Agency has launched various satellites, has utilized the crewed Spacelab module aboard US shuttles, and has sent probes to comets and Mars. It also participates in ISS with its own module and the uncrewed cargo spacecraft ATV.[citation needed]

Currently, ESA has a program for the development of an independent multi-function crewed spacecraft CSTS scheduled for completion in 2018. Further goals include an ambitious plan called the Aurora Programme, which intends to send a human mission to Mars soon after 2030. A set of various landmark missions to reach this goal are currently under consideration. The ESA has a multi-lateral partnership and plans for spacecraft and further missions with foreign participation and co-funding. ESA is also developing Galileo program which seeks to give independence to the EU from the American GPS.[citation needed]

China[edit]

Since 1956 the Chinese have had a space program which was aided early on from 1957 to 1960 by the Soviets. "Dong Fang Hong I" was launched on 24 April 1970 and was the first satellite to be launched by the Chinese. With increased economy and technology strength in the following decades, especially since the early 21st century, China has made significant achievements in many aspects of space activities. It has developed a sizable family of Long March rockets, including Long March 5, the launch vehicle with the highest payload capacity in Asia since 2016[update]. China launched more than 140 spaceflights between 2015 and 2020.[65] China is operating multiple satellite systems, including communication, Earth imaging, weather forecast, ocean monitoring. BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, the satellite navigation system developed, launched, and operated by China, is one of the four core system providers of the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems.[66]

The US Pentagon released a report in 2006, detailing concerns about China's growing presence in space, including its capability for military action.[67] In 2007 China tested a ballistic missile designed to destroy satellites in orbit, which was followed by a US demonstration of a similar capability in 2008.[citation needed]

China Manned Space Program[edit]

The China Manned Space Program, China's human spaceflight program, began in 1992. Following Shenzhou 5, the first successful crewed spaceflight mission in 2003 which made China the third country with independent human spaceflight capability, China has developed critical capabilities including EVA, space docking and berthing and space station. Currently, China's Tiangong Space Station is under construction and the phase one of the project is expected to be completed in 2022.[citation needed]

Chinese Lunar Exploration Program[edit]

As the first step of distance outer space exploration, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program was approved in 2004. It launched two lunar orbiters: Chang'e 1 and Chang'e 2 in 2007 and 2010 respectively. On 14 December 2013, China successfully soft-landed Chang'e 3 Moon lander and its rover Yutu on the Moon's surface, becoming the first Asian country to do so. This was followed by Chang'e 4, the first soft landing on the far side of the Moon, in 2019 and Chang'e 5, the first lunar sample return mission conducted by an Asian country, in 2020, marking the completion of the three goals (orbiting, landing, returning) of the first stage of the program.[65]

Planetary Exploration of China[edit]

China began its first interplanetary exploration attempt in 2011 by sending Yinghuo-1, a Mars orbiter, in a joint mission with Russia. Yet it failed to leave Earth orbit due to the failure of the Russian launch vehicle.[68] As a result, the Chinese space agency then embarked on its independent Mars mission. In July 2020, China launched Tianwen-1, which included an orbiter, a lander, and a rover, on a Long March 5 rocket to Mars. Tianwen-1 was inserted into Mars orbit on 10 February 2021, followed by a successful landing and deployment of the Zhurong rover on 14 May 2021, making China the second country in the world which successfully soft-landed a fully operational spacecraft on Mars surface.[citation needed]

France[edit]

Emmanuel Macron announced on 13 July 2019 the project to create a military command specialising in space, which would be based in Toulouse.[citation needed]

This command should be operational in September 2020 within the Air Force to become the Air and Space Force. Its purpose will be to strengthen France's space power in order to defend its satellites and deepen its knowledge of space. It will also aim to compete with other nations in this new place of strategic confrontation.[69]

Japan[edit]

Japan's space agency, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, is a major space player in Asia. While not maintaining a commercial launch service, Japan has deployed a module in the ISS and operates an uncrewed cargo spacecraft, the H-II Transfer Vehicle.[citation needed]

JAXA has plans to launch a Mars fly-by probe. Their lunar probe, SELENE, is touted as the most sophisticated lunar exploration mission in the post-Apollo era. Japan's Hayabusa probe was humankind's first sample return from an asteroid. IKAROS was the first operational solar sail.[citation needed]

Although Japan developed the HOPE-X, Kankoh-maru, and Fuji crewed capsule spacecraft, none of them have been launched. Japan's current ambition is to deploy a new crewed spacecraft by 2025 and to establish a Moon base by 2030.[citation needed]

Taiwan[edit]

The National Space Organization (NSPO; formerly known as the National Space Program Office) and the National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology are the national civilian space agencies of the democratic industrialized developed country of Taiwan under the auspices of the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan). The National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology is involved in designing and building Taiwanese nuclear weapons,[70][71][72] hypersonic missiles, spacecraft and rockets for launching satellites while the National Space Organization is involved in space exploration, satellite construction, and satellite development as well as related technologies and infrastructure (including the FORMOSAT series of Earth observation satellites similar to NASA[73] along with DARPA {In-Q-Tel} such as Google Earth {Keyhole, Inc} or so forth) and related research in astronautics, quantum physics, materials science with microgravity, aerospace engineering, remote sensing, astrophysics, atmospheric science, information science, design and construction of indigenous Taiwanese satellites and spacecraft, launching satellites and space probes into low Earth orbit.[74][75][76] Additionally, a state of the art crewed spaceflight program is currently in development in Taiwan and is designed to compete directly with the crewed programs of China, United States and Russia. Active research is currently undergoing in the development and deployment of space-based weapons for the defense of national security in Taiwan.[77]

India[edit]

ISRO[edit]

Indian Space Research Organisation, India's national space agency, maintains an active space program. It operates a small commercial launch service and launched a successful uncrewed lunar mission dubbed Chandrayaan-1 in October 2007. India successfully launched an interplanetary mission, Mars Orbiter Mission, in 2013 which reached Mars in September 2014, hence becoming the first country in the world to do a Mars mission in its maiden attempt. On July 22, 2019, India sent Chandrayaan-2 to the Moon, whose Vikram lander crashed on the lunar south pole region on September 6.[citation needed]

Other nations[edit]

Cosmonauts and astronauts from other nations have flown in space, beginning with the flight of Vladimir Remek, a Czech, on a Soviet spacecraft on March 2, 1978. As of November 6, 2013[update], a total of 536 people from 38 countries have gone into space according to the FAI guideline.[citation needed]

Private Companies[edit]

SpaceX (USA)[edit]

Space Exploration Technologies Corp., commonly referred to as SpaceX, is an American spacecraft manufacturer, launch service provider, defense contractor and satellite communications company headquartered in Hawthorne, California. The company was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the goal of reducing space transportation costs and ultimately developing a sustainable colony on Mars. The company currently operates the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets along with the Dragon and Starship spacecraft.

The company offers internet service via its Starlink subsidiary, which became the largest-ever satellite constellation in January 2020 and, as of November 2023, comprised more than 5,000 small satellites in orbit.[78]SpaceX is also planning a fully reusable rocket named Starship. It consists of a first stage named Super Heavy and a second stage also named Starship.

Blue Origin[edit]

Blue Origin made the first reusable space-capable rocket booster, New Shepard (it is suborbital, Falcon 9 was the first orbital). They also originally had the idea of landing rocket boosters on ships at sea, however, SpaceX replicated their idea and did it first. They lead the national team, which is designing a lunar lander and transfer vehicle (Integrated Lander Vehicle). They will contribute by modifying their Blue Moon lunar lander.[citation needed]

Bigelow Aerospace[edit]

Bigelow Aerospace made the first commercial module in space (BEAM). They also designed and manufactured the first inflatable habitats in space (Genesis I and Genesis II). They also plan to make the first commercial space station around the moon (Lunar Depot), perhaps the first ever.[citation needed]

Northrop Grumman[edit]

They make commercial resupply runs to the ISS with their Cygnus spacecraft. They also helped develop non-commercial spacecraft during the space race (Apollo LM as Grumman). They also are a part of the national team, led by Blue Origin which is designing a lunar lander and transfer vehicle (Integrated Lander Vehicle), partly based on Cygnus.[citation needed]

United Launch Alliance[edit]

United Launch Alliance, LLC, commonly referred to as ULA, is an American aerospace manufacturer, defense contractor and launch service provider that manufactures and operates rockets that launch spacecraft into Earth orbit and on trajectories to other bodies in the Solar System. ULA also designed and builds the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage for the Space Launch System (SLS).

The company was formed in December 2006 as a joint venture between Lockheed Martin Space and Boeing Defense, Space & Security.[79] The primary customers of ULA are the Department of Defense (DoD) and NASA.[80] ULA provides launch services using the Atlas V and Vulcan Centaur launch vehicles. Using these and the retired Delta II and Delta IV launch systems, ULA has launched payloads including weather, telecommunications, and national security satellites, scientific probes and orbiters. ULA also launches the Boeing Starliner and commercial satellites.[81] Atlas V will retire after it completes its remaining launches. As of 2024[update], seventeen Atlas V launches remain.

In 2014, ULA began development of the Vulcan Centaur rocket as a successor to the Atlas V and Delta IV, with an initial flight planned for 2019.[82][83] After multiple delays, the maiden flight took place on 8 January 2024[84] with the initial mission launching Astrobotic Technology's Peregrine lunar lander.[85][86]Arianespace[edit]

Arianespace SA is a French company founded in 1980 as the world's first commercial launch service provider.[87] It undertakes the operation and marketing of the Ariane programme.[88] The company offers a number of different launch vehicles: the heavy-lift Ariane 6 for dual launches to geostationary transfer orbit, and the solid-fueled Vega series for lighter payloads.[89]

As of May 2021[update], Arianespace had launched more than 850 satellites[90] in 287 launches over 41 years. The first commercial flight managed by the new entity was Spacenet F1 launched on 23 May 1984. Arianespace uses the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana as its main launch site. It has its headquarters in Évry-Courcouronnes, Essonne, France.[91][92]Rocket Lab[edit]

Rocket Lab USA, Inc. is a publicly traded aerospace manufacturer and launch service provider[93] that operates and launches lightweight Electron orbital rockets[93] used to provide dedicated launch services for small satellites[94] as well as a suborbital variant of Electron called HASTE (Hypersonic Accelerator Suborbital Test Electron).[95] The company plans to build a larger Neutron rocket[96] as early as 2024.[97] Electron rockets have launched 44 times from either Rocket Lab's Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand[93] or at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport in Wallops Island, Virginia, United States.[98] Rocket Lab has launched one HASTE rocket to date from Wallops Island, Virginia.[99]

In addition to the Electron, Neutron and HASTE launch vehicles, Rocket Lab manufactures and operates spacecraft and is a supplier of satellite components including star trackers, reaction wheels, solar cells and arrays, satellite radios, separation systems, as well as flight and ground software.[100]

The company was founded in New Zealand in 2006.[101] By 2009,[102] the successful launch of Ātea-1[102] made the organization the first private company in the Southern Hemisphere to reach space.[101] The company established headquarters in California, US in 2013[103] and developed the expendable[104] Electron rocket.[105] The first launch of the rocket took place in May 2017.[106] In August 2021, the company became a public company, listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange through a SPAC merger.[107] In May 2022, after four years of development, the Electron booster attempted recovery by a helicopter.[108]In 2024, the company announced that a first stage booster that was recovered on an earlier launch will be reused on a future launch, marking the first time Electron would reuse the full first stage.[109]In August 2020 the company launched its first in-house designed and built satellite, Photon.[110]

The company also builds and operates satellites for the Space Development Agency,[111][112] a space-based missile defense program of the United States Space Force established by Michael D. Griffin (who later became a Rocket Lab board member) in his role as Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering during the Trump administration.[113][114] The company's participation drew controversy in New Zealand,[115] where members of parliament noted the company is contributing to the "weaponization of space" and could be in violation of New Zealand's nuclear-free zone laws.[116] The Union of Concerned Scientists warns SDA will escalate global tensions and called the project "fundamentally destabilizing".[117]

Rocket Lab has acquired four companies to expand its space systems offering including Sinclair Interplanetary in April 2020,[118] Advanced Solutions Inc. in December 2021,[119] SolAero Holdings Inc in January 2022,[120] and Planetary Systems Corporation in December 2021.[121]

As of December 2023, the company had approximately 1,650 full time permanent employees globally.[122] Approximately 700 of these employees are based in New Zealand with the remainder in the United States.[123] The acquisition of SolAero added 425 staff members in the United States in January 2022.[124][125]

Two attempts have been made to recover an Electron booster by helicopter.[108][126] In addition, six attempts have been made at soft water recovery.[127][128][129][130] As of 2022, the company is developing the bigger Neutron reusable unibody rocket;[97] multiple spacecraft buses,[131] and rocket engines: Rutherford,[132] Curie,[133] HyperCurie,[134] and Archimedes.[135]See also[edit]

- History of Space in Africa

- History of aviation

- List of crewed spacecraft

- Timeline of spaceflight

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- Human presence in space

Notes[edit]

- ^

- Tsiolkovsky, 1903, Exploration of Outer Space by Means of Rocket Devices

- Goddard, 1919, A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes

- Oberth, 1923, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen

- ^ Project Mercury's first two flights were suborbital flights (listed below), while its latter four flights were orbital flights.

- ^ Includes several special cases. Soyuz 1 and Soyuz 11 were both fatal missions which reached space. Soyuz 19 was the Soviet participant in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, a separate craft from the American Apollo craft which is listed below. Soyuz 32 brought a crew to the Salyut 6 space station, but the crew returned on Soyuz 34, which had been sent to the station without a crew. Soyuz T-10a was an aborted launch attempt which failed to reach space. As orbital flights or committed attempts, all of the above are included in the number. The one crewed Soyuz flight not included in this number is Soyuz 18a, an aborted mission which nevertheless reached space as a suborbital flight, and which is therefore listed separately below.

- ^ Does nt include Apollo 1.

- ^ Represents the American Apollo craft. The Soviet craft, Soyuz 19, is counted in the above Soyuz number.

- ^ Includes two fatal missions: STS-51-L, and STS-107. The former did not reach space, while the latter did.

References[edit]

- ^ "Sputnik | Satellites, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2000). Challenge To Apollo: The Soviet Union and The Space Race, 1945-1974.

- ^ "Yuri Gagarin: First Man in Space". NASA. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "This Day in History: Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova becomes the first woman in space". History.com. June 16, 1963. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Ragin Williams, Catherine; Neesha Hosein; Logan Goodson; Laura A. Rochon; Cassandra V. Miranda (May 2010). "NASA Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Roundup - Pictures in Time" (PDF). The Space Center Roundup. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Shayler, David (3 June 2004). Walking in Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 4. ISBN 9781852337100. Retrieved 19 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Story of Manned Space Stations, 2007, by Philip Baker, SpringerLink p.2 [1]

- ^ Shayler, David (3 June 2004). Walking in Space. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 6. ISBN 9781852337100. Retrieved 19 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Walter Dornberger, Moewig, Berlin 1984. ISBN 3-8118-4341-9

- ^ "Operation Backfire Tests at Altenwalde/Cuxhaven". V2Rocket.com. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "How a Nazi rocket could have put a Briton in space". BBC. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Megaroc". BIS. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ UPPER AIR ROCKET SUMMARY V-2 NO. 20 Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. postwarv2.com

- ^ "The Beginnings of Research in Space Biology at the Air Force Missile Development Center, 1946–1952". History of Research in Space Biology and Biodynamics. NASA. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "V-2 Firing Tables". White Sands Missile Range. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "The First Day In Orbit". Flight. 80 (2736). London: Iliffe Transport Publications: 208. 17 August 1961. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ^ "Geek Trivia: A leap of fakes". 14 September 2004. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Gagarin's Falsified Flight Record". Seeker. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "My steps for Bataan". United States Marine Corps Flagship. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft (Second revision ed.). New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-02-542820-1.

- ^ Gatland (1976), p. 123

- ^ Gatland (1976), p. 129

- ^ Becker, Joachim. "Cosmonaut Biography: Svetlana Savitskaya". www.SpaceFacts.de. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif. Challenge To Apollo The Soviet Union and The Space Race, 1945-1974. NASA. p. 832.

- ^ a b Both the Apollo 11 Moon landing and the ASTP have been identified as the end of the Space Race,Samuels, Richard J., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of United States National Security (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-7619-2927-7.

Most observers felt that the U.S. moon landing ended the space race with a decisive American victory. […] The formal end of the space race occurred with the 1975 joint Apollo-Soyuz mission, in which U.S. and Soviet spacecraft docked, or joined, in orbit while their crews visited one another's craft and performed joint scientific experiments.

- ^ "The First Dryden-Blagonravov Agreement – 1962". NASA History Series. NASA. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Launius, Roger D. (2019-07-10). "First Moon landing was nearly a US–Soviet mission". Nature. 571 (7764): 167–168. Bibcode:2019Natur.571..167L. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02088-4. PMID 31292553. S2CID 195873630.

- ^ Sietzen, Frank (October 2, 1997). "Soviets Planned to Accept JFK's Joint Lunar Mission Offer". SpaceDaily. SpaceCast News Service. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Helen T. Wells; Susan H. Whiteley; Carrie E. Karegeannes (1975). "Origins of NASA Names: Manned SpaceFlight". NASA. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Posaner, Joshua (2022-09-23). "Russia's war in Ukraine upends Europe's space plans". POLITICO. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "The new space race: a high-stakes competition of politics and power". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ Sheldon, John (2016-07-17). "The New Asian Space Race". SpaceWatch.Global. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "How the War in Ukraine is Changing the Space Game". IFRI. 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "Ike in History: Eisenhower Creates NASA". Eisenhower Memorial. 2013. Archived from the original on November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "The National Aeronautics and Space Act". NASA. 2005. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- ^ Bilstein, Roger E. (1996). "From NACA to NASA". NASA SP-4206, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles. NASA. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-16-004259-1. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ "Mercury MA-11". Encyclopedia Astronauticax. Archived from the original on August 23, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2013.

- ^ MSFC, Jennifer Wall (2015-02-23). "What Was the Gemini Program?". NASA. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ White, Mary C. "Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew - Ed White". NASA History Program Office. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "The World's First Space Rendezvous". National Air and Space Museum. 2015-12-15. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (May 25, 1961). Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs (Motion picture (excerpt)). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Accession Number: TNC:200; Digital Identifier: TNC-200-2. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Brooks, et al. 1979, Chapter 11.6: "Apollo 8: The First Lunar Voyage". pp. 274-284

- ^ "NASA - The First Person on the Moon". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2023-01-08.

- ^ "SATURN V LAUNCH VEHICLE FLIGHT EVALUATION REPORT SA-513 SKYLAB 1" (PDF). NASA. 1973. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 340.

- ^ Benson & Compton (1983), p. 371.

- ^ Reichl, Eugen (2019). The Soviet Space Program: The Lunar Mission Years: 1959-1976. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Limited. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7643-5675-9. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Space Race Timeline".

- ^ Ralph H. Didlake, KK5PM; Oleg P. Odinets, RA3DNC (28 September 2007). "Sputnik and Amateur Radio". American Radio Relay League. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "American Radio Relay League | Ham Radio Association and Resources". www.arrl.org. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ^ "Sputnik 1 – NSSDC ID: 1957-001B". NSSDC Master Catalog. NASA.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Trajectory Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "Vostok-2 mission". www.russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "The Almaz program". www.russianspaceweb.com.

- ^ Baker, Philip (2007). The Story of Manned Space Stations: an introduction. Berlin: Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-387-30775-6.

The story of manned space stations: an introduction.

- ^ Jackman, Frank (29 October 2010). "ISS Passing Old Russian Mir In Crewed Time". Aviation Week.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Воздушно-космический Корабль [Air-Space Ship] (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Harvey, Brian (2007). The Rebirth of the Russian Space Programme: 50 Years After Sputnik, New Frontiers. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-38-771356-4. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b Paladini, Steffi (10 February 2021). "In the new space race to Mars, China is hellbent on beating India and others". Scroll.

- ^ "International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (ICG): Members". Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Report: China's Military Space Power Growing" by Leonard David, Space.com, June 5, 2006, Accessed June 8, 2006.

- ^ "Programming glitch, not radiation or satellites, doomed Phobos-Grunt". 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "La France va se doter d'un "commandement de l'espace"".

- ^ Adams, Sam (1 September 2016). "Taiwanese navy accidentally fires NUCLEAR MISSILE at fishing vessel as tensions in China Strait reach boiling point". Mirror.

- ^ "At Mach-10, Taiwan's Hsiung Feng-III 'Anti-China' Missiles could be faster than the BrahMos". Indian Defence News. 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-08-07. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ^ Villasanta, Arthur Dominic (21 October 2016). "Taiwan Extending the Range of its Hsiung Feng III Missiles to Reach China". China Topix.

- ^ Fulco, Matthew (16 December 2015). "Taiwan's Space Program Blasts Off". Taiwan Business Topics.

- ^ "Taiwan To Upgrade 'Cloud Peak' Medium-range Missiles For Micro-Satellites Launch". Defense World. 25 January 2018.

- ^ Everington, Keoni (25 January 2018). "Taiwan's upgraded 'Cloud Peak' missiles could reach Beijing". Taiwan News.

- ^ "Taiwan's New Ballistic Missile Capable of Launching Microsatellites". Spacewatch Asia Pacific. 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Welcome to NSPO". Nspo.narl.org.tw. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan (18 May 2022). "Starlink Launch Statistics". planet4589. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2024-02-11). "Bruno trumpets transformation of ULA after Vulcan launch". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "SpaceX breaks Boeing-Lockheed monopoly on military space launches". Reuters. 2016-04-28. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- ^ Ray, Justin (November 23, 2009). "Atlas 5 launches Intelsat communications satellite". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ Gruss, Mike (April 13, 2015). "ULA's Next Rocket to Be Named Vulcan". SpaceNews. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Grush, Loren (September 27, 2018). "Military's primary launch provider picks Blue Origin's new engine for future rocket". The Verge. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ Bruno, Tory (December 14, 2023). "#VulcanRocket is now in the pipe for its first launch on 8 January". Twitter.

- ^ "NASA Invites Public to Share Excitement of Astrobotic, ULA Robotic Artemis Moon Launch – NASA". 2023-12-19. Retrieved 2023-12-27.

- ^ "The Space Review: The difficult early life of the Centaur upper stage". www.thespacereview.com. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ Jaeger, Ralph-W.; Claudon, Jean-Louis (May 1986). Ariane — The first commercial space transportation system. Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Space Technology and Science. Vol. 2. Tokyo, Japan: AGNE Publishing, Inc. (published 1986). Bibcode:1986spte.conf.1431J. A87-32276 13-12.

- ^ "Arianespace was founded in 1980 as the world's first launch services company". arianespace.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- ^ "Service & Solutions". arianespace.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "Arianespace Company profile". Arianespace. May 5, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "Russians, French sign space contract.(UPI Science Report)." United Press International. 12 April 2005. Retrieved on 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us". Arianespace. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "New Zealand Launch Schedule [Including Past Launches] - RocketLaunch.Live". www.rocketlaunch.live. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "IAF : B4.5 Speed To Space: Dedicated Launch For Small Satellites on Electron". www.iafastro.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Introduces Suborbital Testbed Rocket, Selected for Hypersonic Test Flights". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Neutron". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ a b Roulette, Joey (2022-09-30). "Rocket Lab to fire up first tests of new engine next year - CEO". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Mehta, Aaron (2022-12-07). "New Zealand's Rocket Lab prepares for first launch from US, as it eyes national security growth". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2023-06-18). "Rocket Lab launches first suborbital version of Electron". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Makes its Defense Prime Debut with $0.5 Billion Contract to Design and Build Satellite Constellation for Space Development Agency". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ a b "Rocket Lab USA Poised to Change the Space Industry". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ a b "Ä€tea-1". Gunter's Space Page. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Expands Footprint with New Long Beach Headquarters and Production Complex". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Wall, Mike (2022-11-04). "Rocket Lab launches Swedish satellite but fails to catch booster with helicopter". Space.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Electron". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Completed Missions". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Completes Merger with Vector Acquisition Corporation to Become Publicly Traded End-to-End Space Company". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ a b "Rocket Maker Fails in 1st Bid to Catch, Recover Booster With Helicopter | Aerospace Tech Review". www.aerospacetechreview.com. 2022-05-03. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Returns Previously Flown Electron to Production Line in Preparation for First Reflight". www.businesswire.com. 2024-04-10. Retrieved 2024-04-11.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2020-09-04). "Rocket Lab launches first Photon satellite". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rocket Lab wins $515 million contract to build 18 satellites for U.S. government agency". 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Supports Significant Milestone for DARPA and Space Development Agency". 13 July 2022. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (21 April 2019). "Space Development Agency a huge win for Griffin in his war against the status quo". Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (12 August 2018). "Mike Griffin joins board of Rocket Lab". Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Rocket Lab could be used to make war from space - Green Party". RNZ. 2022-10-16. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Corlett, Eva (17 October 2022). "New Zealand MP says Rocket Lab launches could betray country's anti-nuclear stance". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Space-based Missile Defense". Union of Concerned Scientists. 30 August 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Closes Acquisition of Satellite Hardware Manufacturer Sinclair Interplanetary". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Acquires Space Software Company Advanced Solutions, Inc". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Closes Acquisition of Space Solar Power Products Company SolAero Holdings, Inc". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Closes Acquisition Of Space Hardware Company Planetary Systems Corporation". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "XBRL Viewer". www.sec.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "The Post". www.thepost.co.nz. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ Bellan, Rebecca (January 18, 2022). "Rocket Lab acquires SolAero Holdings for $80M to boost space solar cell production". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Pullar-Strecker, Tom (December 14, 2021). "Most Rocket Lab staff set to be based outside NZ by early next year". Stuff. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Helicopter Was Unable to Catch Booster Before it Fell Into The Pacific". Bloomberg.com. 2022-11-04. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Launch Schedule – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ "Rocket Lab to Recover Electron Booster on Next Mission". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ "Rocket Lab to Recover Electron Rocket, Introduce Helicopter Operations During Next Launch". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2023-03-24). "Rocket Lab launches BlackSky satellites". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Unveils Spacecraft Bus Lineup". Rocket Lab. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ "Rutherford Engine Test Fire". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ "The Kick Stage: Responsible Orbital Deployment". Rocket Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Etherington, Darrell (2020-05-13). "Rocket Lab tests new hyperCurie engine that will power its deep space delivery vehicle". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (2021-12-02). "Neutron switches to methane/oxygen, 1 Meganewton Archimedes engine revealed". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

Bibliography[edit]

- Benson, Charles Dunlap & Compton, William David (1983). Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab. NASA Scientific and Technical Information Office. OCLC 8114293. SP-4208.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Further reading[edit]

Media related to History of spaceflight at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of spaceflight at Wikimedia Commons- Quest: The History of Spaceflight

- Historic spacecraft

![Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP, 1975), first docking between the two competitor states, testing shared docking systems enabling future cooperation programs away from the competition.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Portrait_of_ASTP_crews_-_restoration.jpg/200px-Portrait_of_ASTP_crews_-_restoration.jpg)