Harding and Seaver

| Harding & Seaver | |

|---|---|

| Practice information | |

| Founders | George C. Harding; Henry M. Seaver |

| Founded | 1901 |

| Dissolved | 1947 |

| Location | Pittsfield, Massachusetts |

Harding and Seaver was an architectural firm based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, active from 1902 to 1947. It was the partnership of architects George C. Harding (1867–1921) and Henry M. Seaver (1873–1947).

Biographies of founders[edit]

George C. Harding[edit]

George Campbell Harding was born May 18, 1867, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He attended the public schools in Pittsfield and Phillips Academy in Andover before entering the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. He graduated in 1889 and worked in the offices of several Boston architects. He later returned to Pittsfield, where in 1894 he formed a partnership with Charles T. Rathbun, Pittsfield's oldest architect. This partnership, Rathbun & Harding, was dissolved upon Rathbun's retirement in 1899. Harding then practiced under his own name, establishing his partnership with Henry M. Seaver on January 1, 1902.[1] He maintained his partnership with Seaver until his death in 1921.[2]

Harding died April 23, 1921, in Pittsfield. He never married.[2]

Henry M. Seaver[edit]

Henry Morse Seaver was born March 8, 1873, in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, now part of Boston. He attended the public schools, graduating from Boston English High School in 1890. He entered the office of Boston architects Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, and also attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a two-year architecture program, graduating in 1897. After traveling in Europe, Seaver returned to Boston in 1899 and briefly established an architecture practice. He was selected to design the new Theodore Parker Church in West Roxbury, the congregation of which his parents were members. In 1900, after the church was completed, he moved to Pittsfield, where he became head drafter in the office of George C. Harding.[3] After a year, they formed a partnership which was maintained until Harding's 1921 death. Seaver continued the firm alone under the same name until his own death in 1947.[4]

Seaver was a member of the Planning Board of Pittsfield from its 1924 establishment until his death.[4]

In 1904 Seaver married Alice V. W. Wentworth of Pittsfield.[5] He died December 9, 1947, in Pittsfield.[4]

Legacy[edit]

In 1948, the firm was purchased by architects Prentice Bradley (1906-1997) and Douglas T. Gass, who reorganized it as Bradley & Gass. They dissolved their partnership in 1955, Bradley continuing the practice alone. In 1971 he further reorganized the firm as Bradley Architects.[6] The firm is still in business in Pittsfield.[a]

Harding and Seaver "designed a great many public buildings in the Pittsfield-Berkshire County area, and did many other private commissions throughout New England and in New York State."[3]

Some of their works are listed on the United States National Register of Historic Places.[7]

Architectural works[edit]

- Saint Andrew's Chapel, Washington, Massachusetts (1899, NRHP-listed 1986)[8]

- Martin Memorial Chapel, Pittsfield Cemetery, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1900)[9]

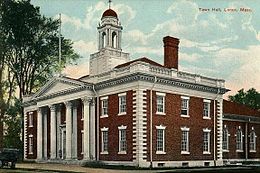

- Lenox Town Hall, Lenox, Massachusetts (1901–02)[10]

- Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1902–03)[11]

- "Mount Pleasant" for W. Murray Crane, Windsor, Massachusetts (1903)[12]

- House for Henry M. Seaver,[b] Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1905)[13]

- Lathrop Hall, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York (1905–06)[14]

- Pittsfield Boys' Club, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1905–06)[11]

- House for William C. Plunkett,[c] Adams, Massachusetts (1907)[15]

- "Sugar Hill" for W. Murray Crane, Dalton, Massachusetts (1907)[16]

- Currier Hall, Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts (1908)[17]

- William R. Plunkett School, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1909, demolished 2014)[18]

- Y. M. C. A. Building (former),[d] Dalton, Massachusetts (1909)[19]

- Y. M. C. A. Building, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1909–10)[11]

- Colgate Hall, Colby–Sawyer College, New London, New Hampshire (1911–12)[20]

- House for Richard H. Stearns,[e] Brookline, Massachusetts (1912)[21]

- Masonic Temple, Bennington, Vermont (1912)[22]

- Colgate Memorial Chapel, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York (1916)[23]

- "Point O'View" for George D. B. Bonbright, Nantucket, Massachusetts[24]

- Z. Marshall Crane School and Library, Windsor, Massachusetts (1919–20)[25]

- Alterations to the South Congregational Church, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1919)[26]

- Clapp Memorial Building, Berkshire Medical Center, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1924)[27]

- Edward A. Jones Memorial Building, Berkshire Medical Center, Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1932)[27]

Gallery of architectural works[edit]

-

Lenox Town Hall, Lenox, Massachusetts, 1901-02.

-

Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 1902-03.

-

Lathrop Hall, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York, 1905-06.

-

House for William C. Plunkett, Adams, Massachusetts, 1907.

-

"Sugar Hill" for W. Murray Crane, Dalton, Massachusetts, 1907.

-

Y. M. C. A. Building, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 1909-10.

-

Colgate Hall, Colby–Sawyer College, New London, New Hampshire, 1911-12.

-

Colgate Memorial Chapel, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York, 1916.

-

Z. Marshall Crane School and Library, Windsor, Massachusetts, 1919-20.

See also[edit]

- George M. Harding (1827–1910), an architect of Portland, Maine and Boston

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "News From the Classes," Technology Review 4, no. 2 (April 1902): 246.

- ^ a b "News From the Classes," Technology Review 23, no. 3 (July 1921): 445-446.

- ^ a b "Theodore Parker Unitarian Church: Boston Landmarks Commission Study Report" (PDF). 1985.

- ^ a b c "Henry Seaver, Architect, Dies at 74," Berkshire County Eagle, December 10, 1947, 1.

- ^ "News From the Classes," Technology Review 6, no. 3 (July 1904): 474.

- ^ "Firm & History", berkshirebradley.com, Bradley Architects, n. d. Accessed February 15, 2021.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Betsy Firedberg, James Parrish and Sarah Poland (March 1986). "National Register of Historic Places: Historic Resources of the Town of Washington, Massachusetts (partial inventory: historic historical and archaeological resources, ca. 1765-1900) / Washington Multiple Resources Area".

- ^ Pittsfield Cemetery NRHP Registration Form (2007)

- ^ "Public Buildings," Engineering Record 44, no. 9 (August 31, 1901): 214.

- ^ a b c Edward Boltwood, The History of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, From the Year 1876 to the Year 1916 (Pittsfield: City of Pittsfield, 1916)

- ^ "WND.30", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "PIT.359", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ Colgate University: Report of the President for the Year 1904-1905 (Hamilton: Colgate University, 1905)

- ^ "ADA.26", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "DAL.6", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "WLL.113", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "PIT.702", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "Business Buildings," Engineering Record 59, no. 13 (March 27, 1909): 46b.

- ^ Bryant F. Tolles Jr. and Carolyn K. Tolles, New Hampshire Architecture: An Illustrated Guide (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1979)

- ^ "BKL.1498", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ Downtown Bennington Historic District (Boundary Increase) NRHP Registration Form (2008)

- ^ "Public Buildings and Schools," Engineering Record 73, no. 14 (April 1, 1916): 153.

- ^ "NAN.1636", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "WND.1", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ "PIT.73", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.

- ^ a b "PIT.W", mhc-macris.net, Massachusetts Historical Commission, n. d.