Hôtel de la Marine

48°52′00.40″N 02°19′23.10″E / 48.8667778°N 2.3230833°E

| Hôtel de la Marine | |

|---|---|

Façade | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| Location | Paris, France |

| Construction started | 1757 |

| Completed | 1774 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ange-Jacques Gabriel |

| Website | |

| https://www.hotel-de-la-marine.paris/en | |

The hôtel de la Marine (also known as the hôtel du Garde-Meuble) is an historic building located on place de la Concorde in Paris,[1] to the east of rue Royale. It was designed and built between 1757 and 1774 by the architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel, on the newly created square first called Place Louis XV.[1] The identical building to its west, constructed at the same time, now houses the hôtel de Crillon and the Automobile Club of France.

The Hôtel de la Marine was originally the home of the royal Garde-Meuble, the office managing the furnishing of all royal properties. Following the French Revolution it became the Ministry of the French Navy, which occupied it until 2015. It was entirely renovated between 2015 and 2021. It now displays the restored 18th century apartments of Marc-Antoine Thierry de Ville-d'Avray, the King's Intendant of the Garde-Meuble, as well the salons and chambers later used by the French Navy. A separate part displays the Al Thani Collection presenting international and inter-cultural works of art from the collection of Sheik Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani.[2]

History[edit]

The decision to create the current Place de la Concorde was originally taken in 1748, as the site for an equestrian statue of Louis XV. The statue celebrated the recovery of the King from a serious illness. The site was on swampy land beside the river at the very edge of Paris, between the gates of the garden of the Tuileries Palace and the Champs Elysees. This construction took place well before the construction of the Rue de Rivoli, the rue Royale, or the bridge over the Seine at that location.[3]

The King owned most of the land, and donated it to the city for the new square. A competition was held for the design, which attracted nineteen different plans, but none of them were acceptable to the King. Instead, he assigned his royal architect, Ange-Jacques Gabriel, who had inherited the title of First Architect of the King from his father, Jacques V Gabriel, to make a fusion of the best ideas.[4] Gabriel borrowed features of the proposals of Germain Boffrand, Pierre Contant d'Ivry and others. The most distinctive feature, the facade of columns facing the square, was largely inspired by the Louvre Colonnade designed by Claude Perrault in 1667–1674. The new plan was approved by the King in December 1755, and construction began in 1758. At that time, the plans for the use of the specific buildings had not been finalised. In 1768 the King decided that the northwest building should become the home of the Garde-Meuble of the Crown, the overseer of royal furnishings.[5]

The new building was one of two structures with identical neoclassical facades on the north side of the square. To the west of the Rue Royale are four separate buildings behind a single facade, which originally were residences of the nobility. Number ten is now houses the Hotel Crillon, The Automobile Club of France occupies number six and number eight. The other building, to the east of Rue Royale,was designated the royal Garde-Meuble, or depot for the royal furniture, art, and other possessions of the crown.[5]

The Hôtel du Garde-Meuble[edit]

The Garde-Meuble of the Crown had been created by Henry IV of France in the 17th century, and its head was given more specific duties by Louis XIV under his chief minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The Intendant of the Garde-Mueuble was a high official who reported directly to the King. Under Colbert, he was assigned to oversee and maintain all the furniture and decorative items of royal residences, including tapestries, and to protect and maintain particularly fine pieces of furniture, labeled as "Furniture of the Crown". These pieces were considered National, not personal property; in 1772, the Garde-Meuble became the first museum of decorative arts in Paris. Its galleries were open to the public on the first Tuesday of each month between Easter and All Saints' Day.[6]

The Garde-Meuble contained a chapel, a library, workshops, stables and apartments, including those of the intendant of the Garde-Meuble – at first Pierre-Élisabeth de Fontanieu (1767–1784), then Marc-Antoine Thierry de Ville-d'Avray (1784–1792) whose apartment has been restored and is on display. Marie-Antoinette also had an apartment there which she used when visiting Paris from the Palace of Versailles.[7]

[edit]

-

Ceremonial cannon taken from the Hôtel de la Marine fired the first shots in the taking of the Bastille, 14 July 1789

-

The execution of Louis XVI on the future Place de la Concorde on 21 January 1793, with the Hotel de la Marine at the right

In 1789 the Hotel held a large collection of weapons, mostly ceremonial, including swords, medieval lances, and two ornate cannon which Louis XIV had received as gifts from the King of Siam. On 13 July 1789, a large crowd angry at the King's decision to dismiss his finance minister Jacques Necker marched to the building, encouraged by the radical orator Camille Desmoulins. The intendant of the Garde-Meuble, Thierry de Ville-d'Array, happened to be absent that day. The acting intendant, frightened by the angry mob, invited the crowd inside the building to take away the weapons and two cannon, but urged them spare the more valuable art, tapestries and furniture. The next morning, 14 July 1789, the two cannon from the Hotel de la Marine fired the first shots at the Bastille, launching the French Revolution.[8]

As the Revolution grew, the King was forced to move with his family from Versailles to Paris in October 1789, to the Tuileries Palace. Some of his valuable possessions were moved to the Conciergerie. It soon took on other duties. The Secretary of State of the Navy, César Henri de la Luzerne, moved his offices to the Garde-Meuble, and from 1789 onwards it housed the naval ministry.[1] UnderAdmiral Decrès, the Navy gradually expanded its offices until by 1798 it occupied the entire building.[6]

In 1792 a remarkable crime took place. A set of diamonds used in the coronation crowns of Louis XV and XVI, including the famous Regent Diamond, had been moved for safe storage to the building. On the night of 16–17 September 1792, the diamonds disappeared. The thieves, Cambon and Douligny, were later caught and guillotined in front of the building (the first executions by the guillotine on the Place de la Concorde).[9]

In 1793, during the Reign of Terror, the portion of the modern Place de la Concorde in front of the neighbouring building, the Palais de Gabriel (now the Hotel Crillon, was the place of execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and, in 1794, of the revolutionary leaders Danton and Robespierre.

Throughout the 19th century the building was modified for the various needs of the Navy. New wings were constructed behind the original building, and a neighbouring building at 5 rue Saint-Florentin was purchased in 1855 and added to the Hôtel. The interiors were also transformed; the salons facing the Place de la Concorde remained in place, but the large hall for the display of large royal furniture pieces was replaced in 1843 by two new salons honouring great moments in French naval history. Much or the original decoration of the rooms was removed, or covered by new works.[10]

The interior decor by Jacques Gondouin, inspired by Piranesi, was an important step forward in 18th-century taste, but it was profoundly distorted by changes under the Second French Empire, although the grands salons d'apparat and the Galerie Dorée still maintain some of the original elements. The building was the scene of several historic events, from a ball honouring the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804, the celebration of the dedication of the Obelisque on the Place de la Concorde by King Louis Philippe in 1836, and the drafting of the decree of the French President abolishing slavery in April 1848.[10]

After the fall of France in June 1940, the Kriegsmarine, the naval forces of Nazi Germany set up their headquarters here. They remained in place up until the Kriegsmarine had to evacuate its presence due to the approach of American and Free French forces in August 1944.[11] In 1989 President François Mitterrand invited foreign leaders to the loggia of the hotel to view the parade celebrating the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution.[11]

National monument[edit]

In 2015, the French government decided to consolidate all of the French military headquarters at a single site, the Hexagon at Ballard in the 15th arrondissement.[1] The navy definitively left the building in 2015. Before its departure, the government considered leasing 12,700 square meters of the building to other tenants, but, after a study of the problem by a commission led by former President Giscard d'Estaing, it was decided to keep the entire building as a public monument under the direction of the Center of National Monuments.[11]

-

Place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde) in about 1791, with the Hôtel de la Marine on the right

-

The Hôtel de la Marine in 1872

Exterior[edit]

-

Facade of the Hôtel de la Marine facing the Place de la Concorde, viewed from the Tuileries Garden

-

Loggia of the Hôtel de la Marine

-

The ceiling of the loggia, with sculpted medallions

The facade of the Hôtel de la Marine was begun in 1755, following the plan of Ange-Jacques Gabriel. As director of the Royal Academy of Architecture, Gabriel provided the ideas and plan, while the details and construction were directed by his deptuty, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, fifteen years younger.[12]

The front facing the square was inspired by the grand classical style of Louis XIV, particularly by the east front of the Louvre Palace, begun in 1667 by Louis Le Vau, architect of Louis XIV, Charles Le Brun, and Charles Perrault. The front is decorated with sculpted medallions and guerlands, another feature borrowed from the Louvre. The long front is balanced at either by two sections with triangular frontons and Corinthian columns.

The distinctive feature of the façade, different from the Louvre, is the loggia, or passageway. The central front, slightly recessed, has a narrow walkway lined with twelve Corinthian columns. The setback of the loggia and the columns create patterns of light and shadow, an essential element of the design.[13]

The ceiling of the loggia is decorated with sculpted octagonal medallions, representing the benefits the King was said to bring to the nation; there are allegorical symbols of music, the arts, industry, agriculture, defense and commerce. They originally also displayed the King's monogram, but the monograms were smashed during the Revolution.[13]

Courtyard of the Intendant[edit]

-

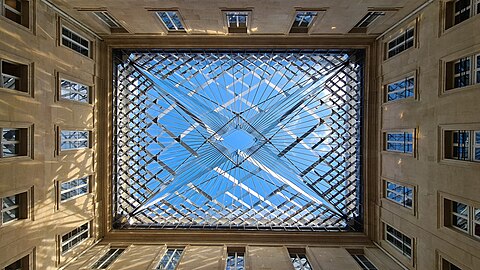

Skylight of the Courtyard of the Intendant

One of the most original elements of the renovation of the building is the new glass skylight over the Courtyard of the Intendant, the entrance point for visitors. It which was created by the architect Hugh Dutton, and is supported by a framework of steel weighing thirty-five tons. Its V-shaped ribs, of polished stainless steel, act as mirrors, which capture and redirect the light in the optimal direction. Though the entire opening is covered with ribs, they cast a minimum of shadows, due to their mirrored covering, and give the very heavy roof an appearance of lightness. The effect is enhanced by the use of glass made with purified iron oxide, which does not change color in the light. The diffusion of light is similar to that created by the facets of the pieces of crystal in the chandeliers of the 18th century.[14]

Apartments of the Intendant[edit]

-

Office of the Intendant Ville d'Avray

-

Angle salon, or Game room of the Intendant Ville d'Avray

-

Dining room of the Intendant Ville d'Avray

A large portion of the east side of the building on the first floor is occupied by the office and apartments of the Intendant of the Garde-Meuble, as it was decorated beginning in 1786 by the Intendant of the time, Marc Antoine Thierry de Ville d'Avray. It contains a reception room, the ceremonial office of the intendant, the bedrooms and bath of the Intendant and his wife, a dining room, a room for entertaining company, The restoration work removed eighteen layers of paint from two centuries before coming to the original decor.[15]

After a simple anteroom, the first room of the apartments is the ceremonial office of the Intendant, lavishly furnished and decorated with paintings and a floor of multicoloured marquetry. His real working office, much simpler, is next to it. Near his bedroom he also had a small study equipped with devices for working with gemstones and making jewellery, a hobby of the Ville-d'Avray.[15] The unfortunate Ville d'Avray de

-

Bed chamber of the Intendant Ville-d'Avray

-

bed chamber of Madame de Ville-d'Avray

-

A gown of Madame de Ville-d'Avray

While the Intendant Thierry De Ville d'Avray was very religious, as reflected in the sober architecture of his bed chamber, his predecessor, Pierre-Élisabeth de Fontanieu, serving between 1770 and 74, had very different taste. He was a libertine, and entertained a wide variety of women in his residence. His taste is illustrated by the decoration of his own bed chamber, and in the Cabinet of Mirrors, with its images of Cherubs painted on the mirrors. De Ville d'Avray had some of the Cherubs repainted to give them a more uplifting tone.[16]

During the restoration of the building that began in 2015, the original office of the Intendant Fontanieu was discovered hidden behind the walls of the more recent naval offices. It still has its original two fireplaces and two notable pieces of its original furniture, a table and a drop-front secretary made by the celebrated furniture craftsman Jean-Henri Riesener (1771), which had previously been on loan to the Louvre Museum and the Palace of Versailles and were returned to their original home in the office.[16]

One other curiosity remains from the office of Intendant Fontanieu; his Cabinet of Physics, where he practiced his hobby of geology. He created false precious stones, using crystal artificially colored, and employed the piece of equipment displayed in the room to trace lines, curves and designs on the jewellery pieces that he made.[17]

The apartments also include the bath of the Intendant Fontanieu, in the classical Louis XVI style, with floral motifs on the furniture made popular by Marie-Antoinette. The bathtub had running hot water, supplied by a large overhead tank hidden above ceiling overhead.[17]

-

Cabinet of mirrors in the apartments of the Intendant Pierre-Élisabeth de Fontanieu (1770-1774)

-

Detail of the Cabinet of Mirrors

-

The Cabinet Doré, Office of the Intendant de Fontanieu (1770-1774)

-

The Cabinet of Physics of Intendant Fontanieu

-

The bath of the Intendant Fontanieu, in the classical Louis XVI style

[edit]

-

The gilded hallway connecting the naval salons

-

Salon of the Admirals

-

Wall decoration honouring Admiral Pierre André de Suffren in Salon of Admirals

-

Fireplace in the Salon of the Admirals

In 1793, During the Revolution, the royal Garde-Meuble was abolished and the French navy took complete occupancy of the building. Beginning in 1843 and particularly during the July Monarchy. some of the rooms that had been used to display the royal furniture were turned into offices, while the rooms along the front of the building, facing the Place de la Concorde, were transformed into salons for naval functions.. The two principal rooms were the Salon d'Honneur and the Salon des Amiraux, or Salon of the Admirals. The walls, ceilings, and doorways were lavishly gilded and decorated with sculpture and mirrors and carvings with nautical themes, including prows of ships, anchors, fish, and sirens. During the reign of King Louis-Phillipe a series of large medallions were added, depicting illustrious figures in French naval history, including Pierre André de Suffren, Jean Bart and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville. These rooms were also sometimes used in the 19th century for non-naval events. Napoleon Bonaparte held a ball there in 1804 to celebrate his coronation as Emperor, and in 1836 Louis-Philippe celebrated the dedication of the Luxor column in the Place de la Concorde.[18]

The Salon of Diplomats was used for more intimate diplomatic meetings until 2015. During the Revolution, in 1792, it was the site of the theft of the royal crown diamonds deposited there (later recovered). It also was equipped with a hidden listening post behind one wall, so that private discussions could be discreetly overheard.[19]

-

The Salon of Diplomats

Art, Decoration, Restoration[edit]

The original function of the building was a depot of decorative objects, and the Hôtel reflects that heritage, and retains to a very rich collection of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, chandeliers, furniture and other decorative art, mostly from the 18th and 19th century. By good fortune, the rooms of the building suffered less looting and destruction during the Revolution than many other Paris landmarks. The curators were able to find many of the original pieces of furniture and decoration at other locations, including the Palace of Versailles and the Elysees Palace.[20]

-

Railing of the Stairway of Honor to first floor, with nautical theme

-

Carrera marble and gilded Water fountain in entry of apartment of the Intendant (18th c.)

-

Tapestry in the salon of guests of Intendant

-

Detail of ceiling decoration, Gilded Gallery

The restoration of the building in the end cost a total of 135 million Euros. Ten million came from French government, 6.7 million from private donors, and 20 million from advertising receipts. The rest was borrowed by the Center of National Monuments, which hopes to recover the cost through future receipts. The project will also receive funding from the rental of offices on the third and fourth floors. These rooms, formerly apartments and storerooms in the old building, were restored to their original appearance, but have no ornate decoration or great historic value.[20]

-

Gilded music box and automaton with Numidian figure, Salon for guests of the Intendant (18th c.)

-

Clock by the maker of chronometers for the French Navy (18th c.)

-

18th-century drop-down desk in the Cabinet Doré by Jean-Henri Riesener (1771)

-

Detail of the Riesener drop-down desk, with bronze ornaments (1771)

The Al Thani Collection[edit]

-

Entrance to the Al Thani Collection at the Hôtel de la Marine

-

13th century Bust of Emperor Hadrian, armor with pearls from 16th c., Al Thani Collection

-

a gold and turquoise plate from the Yarlung Dynasty of Tibet (600-800 AD) in the Al Thani collection

-

Works in the Al Thani Collection

Since the end of 2021 the Hôtel de la Marine has been the venue for the Al Thani Collection, a group of art objects from around the world brought together by Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani of the royal family of Qatar. Under an agreement with the French Ministry of Culture, the gallery will show a rotation of items from the enormous collection of the Al Thani Family for a period of twenty years. The exhibit contains one hundred-twenty works at one time, out of a total in the collection of more than five thousand works. It presents precious objects from ancient civilisations in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Middle East, related by use or theme.[21] One notable object is a marble bust of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, made for Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in about 1240, and then moved centuries later to Venice, where it was set upon shoulders in armor made of gilded enamel, precious stones and pearls.[22]

Bibliography (in French)[edit]

- Hillairet, Jacques (1978). Connaissance du Vieux Paris. Paris: Editions Princesse. ISBN 2-85961-019-7.

- Pommereau, Claude, "Hôtel de la Marine" (June 2021), Beaux Arts Éditions, Paris (ISBN 979-10-204-0646-0)

- "Connaissance des arts" special edition, "L'Hôtel de la Marine", (in French), published September, 2021

External links[edit]

- Hotel de la Marine Official website

- Al Thani Collection Official website

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Hôtel de la Marine". Centre des monuments nationaux. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Connaissance des Arts,""L'Hôtel de la Marine" (2021), p. 6-16

- ^ Hillairet, Jacques, "Connaissance du Vieux Paris" (1956), p. 169

- ^ "Connaissance des arts" special edition, "L'Hôtel de la Marine", October 2021, p. 8

- ^ a b Hillairet, Jacques, "Connaissance du Vieux Paris" (1956), p. 172

- ^ a b "Connaissance des Arts" magazine special edition,""L'Hôtel de la Marine" (October 2021), pp. 6-16

- ^ Hillairet, Jacques, "Connaissance du Vieux Paris" (1956), p. 272

- ^ "Hôtel de la Marine", BeauxArts Ėditions, June 2021, p. 34

- ^ Hillairet, Jacques, "Connaissance du Vieux Paris" (1856), p. 272

- ^ a b "Connaissance des Arts" magazine special edition,""L'Hôtel de la Marine" (October 2021), p.13

- ^ a b c "Connaissance des Arts" magazine special edition, "L'Hôtel de la Marine" (October 2021), p. 15

- ^ "Hôtel de la Marine, Éditions BeauxArts, (June 2021), p. 15

- ^ a b "Hôtel de la Marine", Éditions BeauxArts, (June 2021), p. 12-15

- ^ "L'Hôtel de la Marine", "Connaissance des Arts" special edition, pp.20-21

- ^ a b Beaux Arts Special Editions, "Hotel de la Marine" (June 2021), p.56-58

- ^ a b Beaux Arts Special Editions, "Hotel de la Marine" (June 2021), p.67

- ^ a b Beaux Arts Special Editions, "Hotel de la Marine" (June 2021), p.61

- ^ "Connaissance des arts" special edition, "L'Hôtel de la Marine", September, 2021, pg. 40

- ^ "Beaux Arts Editions", "L'Hôtel de la Marine" (2021), p.72

- ^ a b "Conaissance des Arts", "L'Hôtel de la Marine", pp. 54-55

- ^ "Le Monde", 18 November 2021

- ^ "Connaissance des Arts" magazine special edition,""L'Hôtel de la Marine" (October 2021), p. 64