Guillem d'Areny-Plandolit

Guillem d'Areny-Plandolit | |

|---|---|

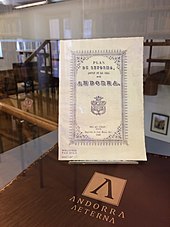

Areny-Plandolit in 1866 | |

| First Syndic of the General Council | |

| In office 28 May 1866 – 2 December 1867 | |

| Co-Princes of Andorra | |

| Preceded by | Joaquim de Riba |

| Succeeded by | Nicolau Duedra |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 February 1822 Seu d'Urgell, Catalonia |

| Died | 23 February 1876 (aged 54) Toulouse, French Republic |

| Nationality | Andorran |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 17 |

| Known for | New Reform of Andorra |

| Awards | |

Guillem Maria d'Areny i de Plandolit, 3rd baron Senaller and Gramenet, (19 February 1822 – 23 February 1876) was an Andorran nobleman and politician.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Guillem d'Areny-Plandolit was born on 19 February 1822, in Seu d'Urgell – close to the Principality of Andorra in the Catalan Pyrenees. The only son of Josep Plandolit Targarona and Maria Rosa Areny,[1][2] Areny-Plandolit belonged to one of the most prominent Catalan families at the time, with a long industrial and commercial background that traces its origins back to the 17th century.[3]

His mother died nine months after his birth, in September. Afterward, Josep and his son moved to Andorra, settling in Ordino where he eventually remarried. Josep died on 17 July 1843, aged 55, after a long illness.[4] In 1841, at the age of 19, Areny-Plandolit married Maria Dolores Parella, Baroness of Senaller.[5] They had seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood.[4]

Wife's murder[edit]

Tragedy struck on 19 June 1855, when his first wife was murdered in Barcelona, where the family had property they frequently visited. Her attacker, Blas Durana Atauri, stabbed her 13 times in a carefully premeditated attack.[6] The crime became well-known in 19th-century Barcelona and shocked the public at the time because of the status and personality of those involved and also for its bizarre aftermath.[7]

Durana was an infantry colonel in the Spanish Army and was stationed in Barcelona at the time. He frequently attended social gatherings where he attempted to climb the social ladder and court women. He soon caught wind of the Baroness and fell deeply in love with her. Parella initially welcomed and tolerated his compliments, but became alarmed when Durana began appearing at an increasing amount of the same gatherings, apparently not letting up.[8]

After complaining to her husband, Areny-Plandolit was annoyed enough to ask his friend, Captain General of Catalonia Juan Zapatero y Navas, for help. Zapatero agreed to post Durana to Lugo in Galicia to mend the situation.[5] Durana was able to continue his amorous siege by making up excuses and taking advantage of every opportunity to return to Barcelona, apparently still motivated by love. Fueled by frustration and envy, this feeling eventually turned into hatred. Desperate and embittered, he decided to kill Parella.[7]

Durana had spent the day of the attack carefully observing the Areny-Plandolit and Parella property, hiding in an alleyway on the opposite street. He attacked the Baroness at dusk when she finally came out of the house in order to visit a theater; she died within twenty minutes.[9] He did not attempt to flee, and was quickly captured by a local militia. He identified himself and triumphantly admitted his crime.[9]

Durana's lawyer tried to argue that mental instability was to blame and referred to past incidents to prove this claim.[10] However, he was quickly convicted and sentenced to be executed by garrote.[11] Although Durana remained calm and composed during the sentencing, the method of execution came unexpectedly since he had expected to be put in front of a firing squad, something more befitting a colonel. His request to change the method of execution was denied.[12][13] Durana committed suicide on the eve of the execution by means of mercuric cyanide, likely smuggled in by an army comrade on an earlier visit to him in prison.[5][14]

Rumors had been going around that the trial had been a farce and that the colonel, as a result of his rank, would somehow be allowed to escape his fate. As a result, a large crowd had gathered on the morning of the execution to witness the event. To avoid a riot, authorities wheeled out his dead body and went through the motions of the execution; essentially executing his corpse.[7][15][16] Areny-Plandolit was not present at the burial of his first wife and appears not to have mourned for long, if at all.[5] He remarried a little more than three months later, to Carolina de Plandolit, his cousin.[17] They had 10 children.[4]

New Reform[edit]

Andorra in the mid-19th century was a country in an economic crisis. Areny-Plandolit led the reforms to replace the aristocratic and oligarchical that previously ruled the state. The political system was largely governed based on the privileges of a small social group formed of traditional wealthy Andorran families, to whom his family also belonged. This type of oligarchical governance made it possible for them to control all the decisions made by the General Council of the Valleys, and to manage public resources as they pleased.[18]

With a total estimated population of only 4,000 residents, whose economic power was growing and eventually even surpassing that of the original wealthy families, more and more voices were demanding social and political changes. The General Council reacted with a steady refusal and inaction. This led to a group of reformists led by Areny-Plandolit to organize meetings in order to discuss the best way to bring about reform.[19] On 22 April 1866, the New Reform was decreed by the Episcopal Co-Prince, Bishop Josep Caixal i Estradé, and established the basis of the Andorran constitution and symbols—such as the tricolor flag—of Andorra. It was ratified three years later by Napoleon III.[20]

The reforms had several effects. Most importantly, it gave every citizen of the country the right to vote. It also promised regular elections; in this case twelve of the 24 councilors were to be elected every two years, with a maximum post length of four years. There was also the creation of the position of town commissioner in order to control public spending and put a halt to the waste of resources.[2] After producing the official document listing the reforms in May 1866, Areny-Plandolit was elected First Syndic of the General Council, a position akin to speaker.[2][21]

Civil orders[edit]

- France

- Commander of the Legion of Honour[22]

- Spain

- Grand Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[22]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Obiols & Miró 2014, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Albert 1988.

- ^ Codina 2006, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Bacquer 1998.

- ^ a b c d Miró 2016.

- ^ Blanche 1862, p. 627.

- ^ a b c El País 2012.

- ^ Correo 2015.

- ^ a b Blanche 1862, p. 628.

- ^ Blanche 1862, p. 631.

- ^ Blanche 1862, p. 629.

- ^ Blanche 1862, p. 632.

- ^ Pallarès 2007.

- ^ Blanche 1862, pp. 633–635.

- ^ Blanche 1862, p. 634.

- ^ Bofarull 2002.

- ^ Pérez 2017.

- ^ Armengol 2009, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Peruga 1998.

- ^ Nacional 2018.

- ^ Armengol 2009, pp. 345–347.

- ^ a b Codina 2006, p. 33.

Sources[edit]

Books

- Albert i Corp, E. (1988). Don Guillem d'Areny i de Plandolit: baró de Senaller i de Gramenet (in Catalan). Editorial Andorra. ISBN 9789991312033.

- Areny-Plandolit, G. (31 May 1866). "Plan of Reform Adopted in the Valleys of Andorra". World Digital Library. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Armengol Aleix, E. (2009). Andorra: un profund i llarg viatge (in Catalan). Andorra: Government of Andorra. ISBN 9789992005491.

- Blanche, A. (1862). Prisiones de Europa (in Spanish). Barcelona: I. Lopez Bernagosi. ISBN 9780428182748.

- Bofarull i Terrades, M. (2002). Crims i misteris de la Barcelona del segle XIX (in Catalan). Barcelona: Rafael Dalmau. ISBN 9788423206438.

- Codina, O. (2006). The Areny-Plandolit House: From Manor House to Noble Residence (PDF). Andorra: Ministeri d’Afers Exteriors. ISBN 9789992004333.

- Guillamet Anton, J. (2009). Andorra: nova aproximació a la història d'Andorra (in Catalan). Andorra: Revista Altaïr. ISBN 9788493622046.

- Obiols i Perearnau, L.; Miró i Tuset, C. (2014). "Batlles, veguers i síndics". La Nacionalitat Andorrana. 26A Diada Andorrana (in Catalan) (26). Societat Andoranna de Cièncie. doi:10.2436/15.8060.02.1.

- Pallarès-Personat, J. (2007). Víctimes i botxins: atemptats i violència política a Catalunya (in Catalan). Barcelona: Dux. ISBN 9788493593315.

- Peruga Guerrero, J. (1998). La crisi de la societat tradicional (S. XIX) (in Catalan). Andorra: Segona Ensenyança. ISBN 9789992001868.

Newspapers

- "Solo se muere dos veces". El Correo (in Spanish). 6 July 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "150 anys de la (nova) Reforma". El Periòdic d'Andorra (in Catalan). 26 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Andorra promulga la Nova Reforma". El Nacional (in Catalan). 22 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "La baronesa María Dolores Parrella murió tras recibir 13 cuchilladas en 1855". El País (in Spanish). 12 August 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

Online sources

- Bacquer, J. (1998). "A Famous Andorran". The Andorran Philatelic Study Circle. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Cahoon, B. "Worldstatesmen: Andorra". Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Guillem de Plandolit i d'Areny". Great Catalan Encyclopedia (in Catalan). Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Miró i Solà, L. (4 November 2016). "L'Assassinat De La Baronessa De Senaller". El Segle XIX a Catalunya (in Catalan). Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Pérez, S. (24 February 2017). "Pau Xavier d'Areny-Plandolit, fundador del primer museo de Andorra". Taxidermidades (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Schemmel, B. (2006). "Countries An-Az". Rulers.org. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

External links[edit]

- Guillem d'Areny-Plandolit at Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana (in Catalan)