George Whitefield

George Whitefield | |

|---|---|

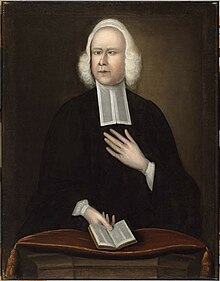

Portrait by Joseph Badger, c, 1745 | |

| Born | 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 |

| Died | 30 September 1770 (aged 55) |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Signature | |

| |

George Whitefield (/ˈhwɪtfiːld/; 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 – 30 September 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an Anglican cleric and evangelist who was one of the founders of Methodism and the evangelical movement.[1][2]

Born in Gloucester, he matriculated at Pembroke College at the University of Oxford in 1732. There he joined the "Holy Club" and was introduced to the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, with whom he would work closely in his later ministry. Unlike the Wesleys, he embraced Calvinism.

Whitefield was ordained after receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree. He immediately began preaching, but he did not settle as the minister of any parish; rather he became an itinerant preacher and evangelist. In 1740, Whitefield traveled to North America where he preached a series of revivals that became part of the "Great Awakening". His methods were controversial, and he engaged in numerous debates and disputes with other clergymen.

Whitefield received widespread recognition during his ministry; he preached at least 18,000 times to perhaps 10 million listeners in Great Britain and her American colonies. Whitefield could enthrall large audiences through a potent combination of drama, religious eloquence, and patriotism. He used the technique of evoking strong emotion, then using the vulnerability of his enthralled audience to preach.[3]

Early life[edit]

Whitefield was born on 27 December [O.S. 16 December] 1714 at the Bell Inn, Southgate Street, Gloucester. Whitefield was the fifth son (seventh and last child) of Thomas Whitefield and Elizabeth Edwards, who kept an inn at Gloucester.[4] His father died when he was only two years old, and he helped his mother with the inn. At an early age, he found that he had a passion and talent for acting in the theatre, a passion that he would carry on with the very theatrical re-enactments of Bible stories he told during his sermons. He was educated at The Crypt School in Gloucester[5] and at Pembroke College, Oxford.[6][7]

Because business at the inn had diminished, Whitefield did not have the means to pay for his tuition.[8] He therefore came up to the University of Oxford as a servitor, the lowest rank of undergraduates. Granted free tuition, he acted as a servant to fellows and fellow-commoners; duties including teaching them in the morning, helping them bathe, cleaning their rooms, carrying their books, and assisting them with work.[8] But, Whitfield would later confess that though he did good works and tried to obey the law of God, he was not yet truly converted to Christ. It was Henry Scougal's book, The Life of God in the Soul of Man, that Whitfield says opened his eyes to the Gospel and led to his conversion. It was that book he says, that God used to show him that he was still lost despite all his attempts to gain the favor of God by means of good works. Only by God's grace can a person realize they have offended God and their need for Jesus Christ, God's Son, and His righteousness imputed to them by faith. Henry Scougal's book showed him the need for a man to be born of God from above, and that this is a supernatural work of the Holy Spirit creating a new heart and a new nature within that wants to serve God, not in order to be saved, but because one has been graciously and undeservedly saved. In 1736, after Whitfield's conversion, the Bishop of Gloucester ordained him a deacon of the Church of England.[1]

Evangelism[edit]

Whitefield preached his first sermon at St Mary de Crypt Church[2] in his home town of Gloucester, a week after his ordination as deacon. The Church of England did not assign him a church, so he began preaching in parks and fields in England on his own, reaching out to people who normally did not attend church. In 1738 he went to Savannah, Georgia in the American colonies as parish priest[citation needed] of Christ Church, which had been founded by John Wesley while he was in Savannah. While there Whitefield decided that one of the great needs of the area was an orphan house. He decided this would be his life's work. In 1739 he returned to England to raise funds, as well as to receive priest's orders. While preparing for his return, he preached to large congregations. At the suggestion of friends he preached to the miners of Kingswood, outside Bristol, in the open air. Because he was returning to Georgia he invited John Wesley to take over his Bristol congregations and to preach in the open air for the first time at Kingswood and then at Blackheath, London.[9]

Whitefield, like many other 18th century Anglican evangelicals such as Augustus Toplady, John Newton, and William Romaine, accepted a plain reading of Article 17—the Church of England's doctrine of predestination—and disagreed with the Wesley brothers' Arminian views on the doctrine of the atonement.[10] However, Whitefield finally did what his friends hoped he would not do—hand over the entire ministry to John Wesley.[11] Whitefield formed and was the president of the first Methodist conference, but he soon relinquished the position to concentrate on evangelical work.[12]

Three churches were established in England in his name—one in Penn Street, Bristol, and two in London, in Moorfields and in Tottenham Court Road—all three of which became known by the name of "Whitefield's Tabernacle". The society meeting at the second Kingswood School at Kingswood was eventually also named Whitefield's Tabernacle. Whitefield acted as chaplain to Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, and some of his followers joined the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, whose chapels were built by Selina, where a form of Calvinistic Methodism similar to Whitefield's was taught. Many of Selina's chapels were built in the English and Welsh counties,[13] and one, Spa Fields Chapel, was erected in London.[14][15]

Bethesda Orphanage[edit]

Whitefield's endeavour to build an orphanage in Georgia was central to his preaching.[4] The Bethesda Orphanage and his preaching comprised the "two-fold task" that occupied the rest of his life.[16] On 25 March 1740, construction began. Whitefield wanted the orphanage to be a place of strong Gospel influence, with a wholesome atmosphere and strong discipline.[17] Having raised the money by his preaching, Whitefield "insisted on sole control of the orphanage". He refused to give the trustees a financial accounting. The trustees also objected to Whitefield's using "a wrong method" to control the children, who "are often kept praying and crying all the night".[4]

In 1740 he engaged Moravian Brethren from Georgia to build an orphanage for negro children on land he had bought in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. Following a theological disagreement, he dismissed them and was unable to complete the building, which the Moravians subsequently bought and completed. This now is the Whitefield House in the center of the Moravian borough of Nazareth, Pennsylvania.[18][19]

Revival meetings[edit]

Beginning in 1740, Whitefield preached nearly every day for months to large crowds as large as eighty thousand people as he travelled throughout the colonies, especially New England. His journey on horseback from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina, was at that time the longest in North America ever documented.[20] Like Jonathan Edwards, he developed a style of preaching that elicited emotional responses from his audiences. But Whitefield had charisma, and his loud voice, his small stature, and even his cross-eyed appearance (which some people took as a mark of divine favor) all served to help make him one of the first celebrities in the American colonies.[21] Like Edwards, Whitefield preached staunchly Calvinist theology that was in line with the "moderate Calvinism" of the Thirty-nine Articles.[22] While explicitly affirming God's sole agency in salvation, Whitefield freely offered the Gospel, saying at the end of his sermons: "Come poor, lost, undone sinner, come just as you are to Christ."[23]

To Whitefield "the gospel message was so critically important that he felt compelled to use all earthly means to get the word out."[24] Thanks to widespread dissemination of print media, perhaps half of all colonists eventually heard about, read about, or read something written by Whitefield. He employed print systematically, sending advance men to put up broadsides and distribute handbills announcing his sermons. He also arranged to have his sermons published.[25] Much of Whitefield's publicity was the work of William Seward, a wealthy layman who accompanied Whitefield. Seward acted as Whitefield's "fund-raiser, business co-ordinator, and publicist". He furnished newspapers and booksellers with material, including copies of Whitefield's writings.[4]

When Whitefield returned to England in 1742, an estimated crowd of 20–30,000 met him.[26] One such open-air congregation took place on Minchinhampton Common, Gloucestershire. Whitefield preached to the "Rodborough congregation"—a gathering of 10,000 people—at a place now known as "Whitefield's tump".[27] Whitefield sought to influence the colonies after he returned to England. He contracted to have his autobiographical Journals published throughout America. These Journals have been characterized as "the ideal vehicle for crafting a public image that could work in his absence." They depicted Whitefield in the "best possible light". When he returned to America for his third tour in 1745, he was better known than when he had left.[28]

Slaveholder and advocate of slavery[edit]

Whitefield was a plantation owner and slaveholder and viewed the work of slaves as essential for funding his orphanage's operations.[29][30] John Wesley denounced slavery as "the sum of all villainies" and detailed its abuses.[31][32] However, defenses of slavery were common among 18th-century Protestants, especially missionaries who used the institution to emphasize God's providence.[33] Whitefield was at first conflicted about slaves. He believed that they were human and was angered that they were treated as "subordinate creatures".[34] Nevertheless, Whitefield and his friend James Habersham played an important role in the reintroduction of slavery to Georgia.[35] Slavery had been outlawed in the young colony of Georgia in 1735.[citation needed] In 1747, Whitefield attributed the financial woes of his Bethesda Orphanage to Georgia's prohibition of black people in the colony.[33] He argued that "the constitution of that colony [Georgia] is very bad, and it is impossible for the inhabitants to subsist" while blacks were banned.[29]

Between 1748 and 1750, Whitefield campaigned for the legalisation of African-American emigration into the colony because the trustees of Georgia had banned slavery. Whitefield argued that the colony would never be prosperous unless slaves were allowed to farm the land.[36] Whitefield wanted slavery legalized for the prosperity of the colony as well as for the financial viability of the Bethesda Orphanage. "Had Negroes been allowed" to live in Georgia, he said, "I should now have had a sufficiency to support a great many orphans without expending above half the sum that has been laid out."[29] Whitefield's push for the legalization of slave emigration in to Georgia "cannot be explained solely on the basics of economics". It was also his hope for their adoption and for their eternal salvation.[37]

Black slaves were permitted to live in Georgia in 1751.[36] Whitefield saw the "legalization of (black residency) as part personal victory and part divine will".[38] Whitefield argued a scriptural justification for black residency as slaves. He increased the number of the black children at his orphanage, using his preaching to raise money to house them. Whitefield became "perhaps the most energetic, and conspicuous, evangelical defender and practitioner of the rights of black people".[4] By propagating such "a theological defense for" black residency, Whitefield helped slaveholders prosper.[37] Upon his death, Whitefield left everything in the orphanage to the Countess of Huntingdon. This included 4,000 acres of land and 49 black slaves.[4]

Campaign against cruel treatment of slaves[edit]

In 1740, during his second visit to America, Whitefield published "an open letter to the planters of South Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland" chastising them for their cruelty to their slaves. He wrote, "I think God has a Quarrel with you for your Abuse of and Cruelty to the poor Negroes."[39] Furthermore, Whitefield wrote: "Your dogs are caressed and fondled at your tables; but your slaves who are frequently styled dogs or beasts, have not an equal privilege."[29] However, Whitefield "stopped short of rendering a moral judgment on slavery itself as an institution".[37]

Whitefield is remembered as one of the first to preach to slaves.[30] Some have claimed that the Bethesda Orphanage "set an example of humane treatment" of black people.[40] Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784), who was a slave, wrote a poem "On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield" in 1770. The first line calls Whitefield a "happy saint".[41]

Relationship with Benjamin Franklin[edit]

Benjamin Franklin attended a revival meeting in Philadelphia and was greatly impressed with Whitefield's ability to deliver a message to such a large group. Franklin had previously dismissed as exaggeration reports of Whitefield preaching to crowds of the order of tens of thousands in England. When listening to Whitefield preaching from the Philadelphia court house, Franklin walked away towards his shop in Market Street until he could no longer hear Whitefield distinctly—Whitefield could be heard over 500 feet. He then estimated his distance from Whitefield and calculated the area of a semicircle centred on Whitefield. Allowing two square feet per person he computed that Whitefield could be heard by over 30,000 people in the open air.[42][43] After one of Whitefield's sermons, Franklin noted the:

wonderful ... change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

— Franklin 1888, p. 135

Franklin was an ecumenist and approved of Whitefield's appeal to members of many denominations but unlike Whitefield was not an evangelical. He admired Whitefield as a fellow intellectual, and published several of his tracts, but thought Whitefield's plan to run an orphanage in Georgia would lose money. A lifelong close friendship developed between the revivalist preacher and the worldly Franklin.[44] True loyalty based on genuine affection, coupled with a high value placed on friendship, helped their association grow stronger over time.[45] Letters exchanged between Franklin and Whitefield can be found at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.[46] These letters document the creation of an orphanage for boys named the Charity School. In 1749, Franklin chose the Whitefield meeting house, with its Charity School, to be purchased as the site of the newly-formed Academy of Philadelphia which opened in 1751, followed in 1755 with the College of Philadelphia, both the predecessors of the University of Pennsylvania. A statue of George Whitefield was located in the Dormitory Quadrangle, standing in front of the Morris and Bodine sections of the present Ware College House on the University of Pennsylvania campus.[47] On 2 July 2020, the University of Pennsylvania announced they would be removing the statue because of Whitefield's connection to slavery.[48]

Marriage[edit]

| Timeline of Whitefield's travel to America[49] | |

|---|---|

| 1738 | First voyage to America, Spent three months in Georgia. |

| 1740–1741 | Second voyage to America. Established Bethesda Orphan House. Preached in New England. |

| 1745–1748 | Third voyage to America. In poor health. |

| 1751–1752 | Fourth voyage to America. |

| 1754 | Fifth voyage to America. |

| 1763–1765 | Sixth voyage to America. Travelled east coast. |

| 1770 | Seventh voyage to America. Wintered in Georgia, then travelled to New England where he died. |

"I believe it is God's will that I should marry", George Whitefield wrote to a friend in 1740.[50] But he was concerned: "I pray God that I may not have a wife till I can live as though I had none." That ambivalence—believing God willed a wife, yet wanting to live as if without one—brought Whitefield a disappointing love life and a largely unhappy marriage.[50]

On 14 November 1741 Whitefield married Elizabeth (née Gwynne), a widow previously known as Elizabeth James.[51] After their 1744–1748 stay in America, she never accompanied him on his travels. Whitefield reflected that "none in America could bear her". His wife believed that she had been "but a load and burden" to him.[52] In 1743 after four miscarriages, Elizabeth bore the couple's only child, a son. The baby died at four months old.[50] Twenty-five years later, Elizabeth died of a fever on 9 August 1768 and was buried in a vault at the Tottenham Court Road Chapel. At the end of the 19th century the Chapel needed restoration and all those interred there, except Augustus Toplady, were moved to Chingford Mount cemetery in north London; her grave is unmarked in its new location.[4][53]

Cornelius Winter, who for a time lived with the Whitefields, observed of Whitefield, "He was not happy in his wife." And, "He did not intentionally make his wife unhappy. He always preserved great decency and decorum in his conduct towards her. Her death set his mind much at liberty."[52][54] After Elizabeth's death, however, Whitfield said, “I feel the loss of my right hand daily.”[55]

Death and legacy[edit]

In 1770, the 55-year-old Whitefield continued preaching in spite of poor health. He said, "I would rather wear out than rust out." His last sermon was preached in a field "atop a large barrel".[56] The next morning, 30 September 1770, Whitefield died in the parsonage of Old South Presbyterian Church,[57] Newburyport, Massachusetts, and was buried, according to his wishes, in a crypt under the pulpit of this church.[4] A bust of Whitefield is in the collection of the Gloucester City Museum & Art Gallery.

It was John Wesley who preached his funeral sermon in London, at Whitefield's request.[58]

Whitefield left almost £1,500 (equivalent to £221,000 in 2021) to friends and family. Furthermore, he had deposited £1,000 (equivalent to £147,000 in 2021) for his wife if he predeceased her and had contributed £3,300 (equivalent to £487,000 in 2021) to the Bethesda Orphanage. "Questions concerning the source of his personal wealth dogged his memory. His will stated that all this money had lately been left him 'in a most unexpected way and unthought of means.'"[4]

In an age when crossing the Atlantic Ocean was a long and hazardous adventure, he visited America seven times, making 13 ocean crossings in total. (He died in America.) It is estimated that throughout his life, he preached more than 18,000 formal sermons, of which 78 have been published.[59] In addition to his work in North America and England, he made 15 journeys to Scotland—most famously to the "Preaching Braes" of Cambuslang in 1742—two journeys to Ireland, and one each to Bermuda, Gibraltar, and the Netherlands.[60] In England and Wales, Whitefield's itinerary included every county.[61]

Whitfield County, Georgia, is named after Whitefield.[62] When the act by the Georgia General Assembly was written to create the county, the "e" was omitted from the spelling of the name to reflect the pronunciation of the name.[63]

George Whitefield College, Whitefield College of the Bible, and Whitefield Theological Seminary are all named after him. The Banner of Truth Trust's logo depicts Whitefield preaching.[64]

Kidd 2014, pp. 260–263 summarizes Whitefield's legacy.

- "Whitefield was the most influential Anglo-American evangelical leader of the eighteenth century."

- "He also indelibly marked the character of evangelical Christianity."

- He "was the first internationally famous itinerant preacher and the first modern transatlantic celebrity of any kind."

- "Perhaps he was the greatest evangelical preacher that the world has ever seen."

Mark Galli wrote of Whitefield's legacy:

George Whitefield was probably the most famous religious figure of the eighteenth century. Newspapers called him the 'marvel of the age'. Whitefield was a preacher capable of commanding thousands on two continents through the sheer power of his oratory. In his lifetime, he preached at least 18,000 times to perhaps 10 million hearers.

— Galli 2010, p. 63

Relation to other Methodist leaders[edit]

In terms of theology, Whitefield, unlike Wesley, was a supporter of Calvinism.[65] The two differed on eternal election, final perseverance, and sanctification, but were reconciled as friends and co-workers, each going his own way. It is a prevailing misconception that Whitefield was not primarily an organizer like Wesley. However, as Luke Tyerman, a historian of Wesley, states, "It is notable that the first Calvinistic Methodist Association was held eighteen months before Wesley held his first Methodist Conference."[66] He was a man of profound experience, which he communicated to audiences with clarity and passion. His patronization by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, reflected this emphasis on practice.

Opposition and controversy[edit]

Whitefield welcomed opposition because as he said, "the more I am opposed, the more joy I feel".[67] He proved himself adept at creating controversy. In his 1740 visit to Charles Town, it "took Whitefield only four days to plunge Charles Town into religious and social controversy."[68] Whitefield thought he might be martyred for his views. After he attacked the established church he predicted that he would "be set at nought by the Rabbies of our Church, and perhaps at last be killed by them".[4]

Clergy[edit]

Whitefield chastised other clergy for teaching only "the shell and shadow of religion" because they did not hold the necessity of a new birth, without which a person would be "thrust down into Hell".[4] In his 1740–41 visit to North America (as he had done in England), he attacked other clergy (mostly Anglican) calling them "God's persecutors". He said that Edmund Gibson, Bishop of London with supervision over Anglican clergy in America,[69] knew no "more of Christianity, than Mahaomet, or an Infidel".[4] After Whitefield preached at St. Philip's Episcopal Church, Charleston, South Carolina, the Commissary, Alexander Garden, suspended him as a "vagabond clergyman." After being suspended, Whitefield attacked all South Carolina's Anglican clergy in print. Whitefield issued a blanket indictment of New England's Congregational ministers for their "lack of zeal".[4]

In 1740, Whitefield published attacks on "the works of two of Anglicanism's revered seventeenth-century authors". Whitefield wrote that John Tillotson, archbishop of Canterbury (1691–1694), had "no more been a true Christian than had Muhammad". He also attacked Richard Allestree's The Whole Duty of Man, one of Anglicanism's most popular spiritual tracts. At least once Whitefield had his followers burn the tract "with great Detestation".[4] In England and Scotland (1741–1744), Whitefield bitterly accused John Wesley of undermining his work. He preached against Wesley, arguing that Wesley's attacks on predestination had alienated "very many of my spiritual children". Wesley replied that Whitefield's attacks were "treacherous" and that Whitefield had made himself "odious and contemptible". However, the two reconciled in later life. Along with Wesley, Whitefield had been influenced by the Moravian Church, but in 1753 he condemned them and attacked their leader, Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf, and their practices. When Joseph Trapp criticized Whitefield's Journals, Whitefield retorted that Trapp was "no Christian but a servant of Satan".[4]

English, Scottish, and American clergy attacked Whitefield, often in response to his attacks on them and Anglicanism. Early in his career, Whitefield criticized the Church of England. In response, clergy called Whitefield one of "the young quacks in divinity" who are "breaking the peace and unity" of the church. From 1738 to 1741, Whitefield issued seven Journals.[70] A sermon in St Paul's Cathedral depicted them as "a medley of vanity, and nonsense, and blasphemy jumbled together". Trapp called the Journals "blasphemous" and accused Whitefield of being "besotted either with pride or madness".[4] In England, by 1739 when he was ordained priest,[71] Whitefield wrote that "the spirit of the clergy began to be much embittered" and that "churches were gradually denied me".[72] In response to Whitefield's Journals, the bishop of London, Edmund Gibson, published a 1739 pastoral letter criticizing Whitefield.[73][74] Whitefield responded by labelling Anglican clergy as "lazy, non-spiritual, and pleasure seeking". He rejected ecclesiastical authority claiming that 'the whole world is now my parish'.[4]

In 1740, Whitefield had attacked Tillotson and Richard Allestree's The Whole Duty of Man. These attacks resulted in hostile responses and reduced attendance at his London open-air preaching.[4] In 1741, Whitefield made his first visit to Scotland at the invitation of "Ralph and Ebenezer Erskine, leaders of the breakaway Associate Presbytery. When they demanded and Whitefield refused that he preach only in their churches, they attacked him as a "sorcerer" and a "vain-glorious, self-seeking, puffed-up creature". In addition, Whitefield's collecting money for his Bethesda orphanage, combined with the hysteria evoked by his open-air sermons, resulted in bitter attacks in Edinburgh and Glasgow."[4]

Whitefield's itinerant preaching throughout the colonies was opposed by Bishop Benson who had ordained him for a settled ministry in Georgia. Whitefield replied that if bishops did not authorize his itinerant preaching, God would give him the authority.[4] In 1740, Jonathan Edwards invited Whitefield to preach in his church in Northampton. Edwards was "deeply disturbed by his unqualified appeals to emotion, his openly judging those he considered unconverted, and his demand for instant conversions". Whitefield refused to discuss Edwards' misgivings with him. Later, Edwards delivered a series of sermons containing but "thinly veiled critiques" of Whitefield's preaching, "warning against over-dependence upon a preacher's eloquence and fervency".[4] During Whitefield's 1744–1748 visit to America, ten critical pamphlets were published, two by officials of Harvard and Yale. This criticism was in part evoked by Whitefield's criticism of "their education and Christian commitment" in his Journal of 1741. Whitefield saw this opposition as "a conspiracy" against him.[4] Whitefield would be derided with names such as "Dr. Squintum", mocking him for his esotropia.[75]

Laity[edit]

When Whitefield preached in a dissenting church and "the congregation's response was dismal," he ascribed the response to "the people's being hardened" as were "Pharaoh and the Egyptians" in the Bible.[76]

Many New Englanders claimed that Whitefield destroyed "New England's orderly parish system, communities, and even families". The "Declaration of the Association of the County of New Haven, 1745" stated that after Whitefield's preaching "religion is now in a far worse state than it was".[4] After Whitefield preached in Charlestown, a local newspaper article attacked him as "blasphemous, uncharitable, and unreasonable."[77] After Whitefield condemned Moravians and their practices, his former London printer (a Moravian) called Whitefield "a Mahomet, a Caesar, an imposter, a Don Quixote, a devil, the beast, the man of sin, the Antichrist".[4]

In the open air in Dublin, Ireland (1757), Whitefield condemned Roman Catholicism, inciting an attack by "hundreds and hundreds of papists" who cursed and wounded him severely and smashed his portable pulpit.[4] On various occasions, a woman assaulted Whitefield with "scissors and a pistol, and her teeth". "Stones and dead cats" were thrown at him. A man almost killed him with a brass-headed cane. "Another climbed a tree to urinate on him."[78] In 1760, Whitefield was burlesqued by Samuel Foote in The Minor.[79]

Nobility[edit]

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, made Whitefield her personal chaplain. In her chapel, it was noted that his preaching was "more Considered among persons of a Superior Rank" who attended the countess's services. Whitefield was humble before the countess saying that he cried when he was "thinking of your Ladyship's condescending to patronize such a dead dog as I am". He now said that he "highly esteemed bishops of the Church of England because of their sacred character". He confessed that in "many things" he had "judged and acted wrong" and had "been too bitter in my zeal". In 1763, in a defense of Methodism, Whitefield "repeated contrition for much contained in his Journals".[4]

Among the nobility who heard Whitefield in the Countess of Huntingdon's home was Lady Townshend.[80] Regarding the changes in Whitefield, someone asked Lady Townshend, "Pray, madam, is it true that Whitefield has recanted?" She replied, "No, sir, he has only canted."[81] One meaning of cant is "to affect religious or pietistic phraseology, especially as a matter of fashion or profession; to talk unreally or hypocritically with an affectation of goodness or piety".[82]

Religious innovation[edit]

In the First Great Awakening, rather than listening demurely to preachers, people groaned and roared in enthusiastic emotion. Whitefield was a "passionate preacher" who often "shed tears". Underlying this was his conviction that genuine religion "engaged the heart, not just the head".[83] In his preaching, Whitefield used rhetorical ploys that were characteristic of theater, an artistic medium largely unknown in colonial America. Harry S. Stout refers to him as a "divine dramatist" and ascribes his success to the theatrical sermons which laid foundations to a new form of pulpit oratory.[84] Whitefield's "Abraham Offering His Son Isaac" is an example of a sermon whose whole structure resembles a theatrical play.[85]

Divinity schools opened to challenge the hegemony of Yale and Harvard; personal experience became more important than formal education for preachers. Such concepts and habits formed a necessary foundation for the American Revolution.[86] Whitefield's preaching bolstered "the evolving republican ideology that sought local democratic control of civil affairs and freedom from monarchial and parliamentary intrusion."[87]

Works[edit]

Whitefield's sermons were widely reputed to inspire his audience's devotion. Many of them, as well as his letters and journals, were published during his lifetime. He was an excellent orator as well, strong in voice and adept at extemporaneity.[88] His voice was so expressive that people are said to have wept just hearing him allude to "Mesopotamia". His journals, originally intended only for private circulation, were first published by Thomas Cooper.[89][90] James Hutton then published a version with Whitefield's approval. His exuberant and "too apostolical" language were criticised; his journals were no longer published after 1741.[91]

Whitefield prepared a new installment in 1744–45, but it was not published until 1938. 19th-century biographies generally refer to his earlier work, A Short Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield (1740), which covered his life up to his ordination. In 1747 he published A Further Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield, covering the period from his ordination to his first voyage to Georgia. In 1756, a vigorously edited version of his journals and autobiographical accounts was published.[92][93] Whitefield was "profoundly image-conscious". His writings were "intended to convey Whitefield and his life as a model for biblical ethics ... , as humble and pious".[94]

After Whitefield's death, John Gillies, a Glasgow friend, published a memoir and six volumes of works, comprising three volumes of letters, a volume of tracts, and two volumes of sermons. Another collection of sermons was published just before he left London for the last time in 1769. These were disowned by Whitefield and Gillies, who tried to buy all copies and pulp them. They had been taken down in shorthand, but Whitefield said that they made him say nonsense on occasion. These sermons were included in a 19th-century volume, Sermons on Important Subjects, along with the "approved" sermons from the Works. An edition of the journals, in one volume, was edited by William Wale in 1905. This was reprinted with additional material in 1960 by the Banner of Truth Trust. It lacks the Bermuda journal entries found in Gillies' biography and the quotes from manuscript journals found in 19th-century biographies. A comparison of this edition with the original 18th-century publications shows numerous omissions—some minor and a few major.[95]

Whitefield also wrote several hymns and revised one by Charles Wesley. Wesley composed a hymn in 1739, "Hark, how all the welkin rings"; Whitefield revised the opening couplet in 1758 for "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing".[96]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b "George Whitefield: Methodist evangelist". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. n.d. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b Heighway 1985, p. 141.

- ^ Scribner 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Schlenther 2010.

- ^ "Old Cryptonians". Crypt School. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Galli 2010.

- ^ "A letter to the Reverend Dr. Durell, vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford; occasioned by a late expulsion of six students from Edmund-Hall. / By George Whitefield, M.A. late of Pembroke-College, Oxford; and Chaplain to the Countess of Huntingdon". University of Oxford Text Archive. University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b Dallimore 2010, p. 13.

- ^ "Whitefield's Mount". Brethren Archive. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Walsh 1993, p. 2.

- ^ Wiersbe 2009, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Anon 2010, p. 680.

- ^ White 2011, pp. 136–150.

- ^ "Coldbath Fields and Spa Fields". British History Online. Cassell, Petter & Galpin. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Tyson 2011, pp. 28–40.

- ^ Williams 1968.

- ^ Diane Severance and Dan Graves, "Whitefield's Bethesda Orphanage"

- ^ "History of Nazareth"

- ^ "Welcome to Moravian Historical Society, Your family's place to discover history". moravianhistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "George Whitefield". Digital Puritan. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "George Whitefield: Did You Know?". Christian History. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Whitefield 2001, p. 3:383.

- ^ Bormann 1985, p. 73.

- ^ Kidd 2014, p. 260.

- ^ Stout 1991, p. 38.

- ^ MacFarlan 1847, p. 65.

- ^ "VCH Gloucestershire, Volume 11 - Minchinhampton: Protestant nonconformity". Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Mahaffey 2007, pp. 107, 112, 115.

- ^ a b c d Galli 1993b.

- ^ a b Kidd 2015.

- ^ Wesley 1774.

- ^ Yrigoyen & Daugherty 1999.

- ^ a b Koch 2015, pp. 369–393.

- ^ Parr 2015, pp. 5, 65.

- ^ Babb 2013.

- ^ a b Dallimore 2010, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Stein 2009, p. 243.

- ^ Parr 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Parr 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Cashin 2001, p. 75.

- ^ "On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield. 1770" bartleby.com. Accessed September 15, 2022.

- ^ Franklin 1888, p. 135.

- ^ Hoffer 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Gragg 1978, p. 574.

- ^ Brands 2000, p. 138–150.

- ^ Letter to George Whitefield; Philadelphia, June 17, 1753. American Philosophical Society Library. 7 April 1882. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "George Whitefield Statue". Penn State University. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Penn announces plans to remove statue of George Whitefield and forms working group to study campus names and iconography". Penn Today. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Time Line adapted from "The Life of George Whitefield: A Timeline 1714–1770"

- ^ a b c Galli 1993a.

- ^ Dallimore 1980, pp. 101, 109.

- ^ a b Schlenther, Boyd Stanley (2010) [2004]. "Whitefield, George (1714–1770)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29281 (2004). "Whitefield, George (1714–1770), Calvinistic Methodist leader". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29281. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - ^ "The Life of George Whitefield". Banner of Truth USA. 13 May 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Select Reviews of Literature, and Spirit of Foreign Magazines. 1809.

- ^ "Whitefield's Curious Love Life | Christian History Magazine". Christian History Institute. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Galli 2010, p. 66.

- ^ First Presbyterian (Old South) Church.

- ^ Wesley, John (1951). "Entry for Nov. 10, 1770" (online). The Journal of John Wesley. Chicago: Moody Press. p. 202.

- ^ Sermons of George Whitefield that have never yet been reprinted, Quinta.

- ^ Gledstone 1871, p. 38.

- ^ "George Whitefield Author Biography". Banner of Truth USA. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "George Whitefield historical marker". Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Whitfield County History". Whitfield County. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Our Mission". Banner of Truth Trust. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Maddock 2012.

- ^ Dallimore 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Kidd 2014, pp. 23, 117.

- ^ Witzig 2008.

- ^ Anderson 1856, p. 187.

- ^ Seven Journals 1738–1741

- ^ "Cambridge, George Owen (1736–1739) (CCEd Person ID 38535)". The Clergy of the Church of England Database 1540–1835. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ White 1855, p. 330.

- ^ Daniels 1883, p. 173.

- ^ Gibson 1801.

- ^ Corbett, P. Scott; Precht, Jay; Janssen, Volker; Lund, John M.; Pfannestiel, Todd; Vickery, Paul; Waskiewicz, Sylvie (2014). U.S. History. OpenStax. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-947172-08-1.

On the left is an illustration for Whitefield's memoirs, while on the right is a cartoon satirizing the circus-like atmosphere that his preaching seemed to attract (Dr. Squintum was a nickname for Whitefield, who was cross-eyed).

- ^ Witzig 2008, p. 139.

- ^ Witzig 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Choi 2014.

- ^ Gordon 1900.

- ^ The Countess of Huntingdon's New Magazine. Partridge and Oakey. 1850. p. 310.

- ^ Walsh, Littell & Smith 1833, p. 467.

- ^ "cant, v.3." Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press, March 2016. Web. 1 April 2016.

- ^ Kidd 2014, p. 65.

- ^ Stout|first=Harry S. |title=The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism|year=1991|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- ^ Pokojska & Romanowska 2012, p. 211.

- ^ Ruttenburg 1993, pp. 429–458.

- ^ Mahaffey 2007, p. 107.

- ^ "George Whitefield". Christian History. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "George Whitefield's Journals". Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Lam & Smith 1944.

- ^ Lambert 2002, pp. 77–84.

- ^ Kidd 2014, p. 269.

- ^ "The Works of George Whitefield Journals" (PDF). Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Parr 2015, pp. 12, 16.

- ^ "The Works of George Whitefield". Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Bowler, Gerry (29 December 2013), "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing", UM Today, University of Manitoba.

References[edit]

- Anderson, James Stuart Murray (1856). The History of the Church of England in the Colonies and Foreign Dependencies of the British Empire. Rivingtons.

- Anon (2010). Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints. Church Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89869-637-0.

- Babb, Tara Leigh (2013). "Without A Few Negroes": George Whitefield, James Habersham, and Bethesda Orphan House In the Story of Legalizing Slavery In Colonial Georgia (Thesis). University of South Carolina.

- Brands, H. W. (2000). The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-49328-4.

- Cashin, Edward J. (2001). Beloved Bethesda: A History of George Whitefield's Home for Boys, 1740–2000. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-722-3.

- Choi, Peter (17 December 2014). "Revivalist, Pop Idol, and Revolutionary Too? Whitefield's place in American history". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

- Choiński, Michał (2016). The Rhetoric of the Revival: The Language of the Great Awakening Preachers. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-647-56023-6.

- Dallimore, Arnold A. (1980). George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival. Vol. II. Edinburgh or Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust. ISBN 978-0-85151-300-3.

- Dallimore, Arnold A. (2010) [1990]. George Whitefield: God's Anointed Servant in the Great Revival of the Enlightened Century. Westchester, Illinois: Crossway Books. ISBN 978-1-4335-1341-1.

- Daniels, W. H. (1883). The Illustrated History of Methodism in Great Britain, America, and Australia: From the Days of the Wesleys to the Present Time. Methodist Book Concern – via Phillips & Hunt.

- Franklin, Benjamin (1888). The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Galli, Mark (1993a). "Whitefield's Curious Love Life". Christian History. No. 38. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Galli, Mark (1993b). "Slaveholding Evangelist: Whitefield's Troubling Mix of Views". Christian History. No. 38. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Galli, Mark (2010). "George Whitefield: Sensational Evangelist of Britain and America". 131 Christians Everyone Should Know. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-0-8054-9040-4. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Gibson, Edmund (1801). A Caution against Enthusiasm. Being the second part of the late Bishop of London's fourth Pastoral Letter. [A criticism of passages from the Journal of George Whitefield.] A new edition. F. & C. Rivington.

- Gledstone, James Paterson (1871). The Life and Travels of George Whitefield, M. A. Longmans, Green, and Company.

- Gordon, Alexander (1900). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 61. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Gragg, Larry (September 1978). "A Mere Civil Friendship: Franklin and Whitefield". History Today. 28 (9): 574.

- Heighway, Carolyn M. (1985). Gloucester: a history and guide. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-256-7.

- Hoffer, Peter Charles (2011). When Benjamin Franklin Met the Reverend Whitefield: Enlightenment, Revival, and the Power of the Printed Word. JHU Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4214-0311-3.

- Kidd, Thomas S. (2014). George Whitefield: America's Spiritual Founding Father. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18162-3.

- Kidd, Thomas (2015). "George Whitefield's troubled relationship to race and slavery". Christian Century. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Koch, Philippa (2015). "Slavery, Mission, and the Perils of Providence in Eighteenth-Century Christianity: The Writings of Whitefield and the Halle Pietists". Church History. 84 (2): 369–393. doi:10.1017/S0009640715000098. ISSN 0009-6407. S2CID 163637671.

- Lambert, Frank (2002). Pedlar in Divinity: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals, 1737–1770. Princeton University Press. pp. 77–84. ISBN 9780691096162.

- MacFarlan, D. (1847). The Revivals of the Eighteenth Century: particularly at Cambuslang. Edinburgh: Johnstone and Hunter. p. 65.

- Mahaffey, Jerome (2007). Preaching Politics: The Religious Rhetoric of George Whitefield and the Founding of a New Nation. Waco: Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-88-1.

- Maddock, Ian J (2012). Men of One Book: A Comparison of Two Methodist Preachers, John Wesley and George Whitefield. Lutterworth. ISBN 978-0-7188-4093-8.

- Lam, George L.; Smith, Warren H. (1944). "Two Rival Editions of George Whitefield's Journal, London, 1738". Studies in Philology. 41 (1): 86–93. ISSN 1543-0383. JSTOR 4172646.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History [4 Volumes]: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3.

- Parr, Jessica M. (2015). Inventing George Whitefield: Race, Revivalism, and the Making of a Religious Icon. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62674-498-1.

- Pokojska, Agnieszka; Romanowska, Agnieszka (2012). Eyes to Wonder, Tongue to Praise: Volume in Honour of Professor Marta Gibińska. Wydawnictwo UJ. ISBN 978-83-233-8769-5.

- Ruttenburg, Nancy (1993). "George Whitefield, Spectacular Conversion, and the Rise of Democratic Personality". American Literary History. 5 (3): 429–58. doi:10.1093/alh/5.3.429. ISSN 0896-7148. JSTOR 490000.

- Schlenther, Boyd Stanley (2010) [2004]. "Whitefield, George (1714–1770)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29281.

- Scribner, Vaughn (2016). "Transatlantic Actors: The Intertwining Stages of George Whitefield and Lewis Hallam Sr., 1739–1756". Journal of Social History. 50 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1093/jsh/shw006. ISSN 1527-1897. S2CID 147286975.

- Stein, Stephen J. (2009). "George Whitefield on Slavery: Some New Evidence". Church History. 42 (2): 243–256. doi:10.2307/3163671. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3163671. S2CID 159671880.

- Stout, Harry S. (1991). The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Tyson, John R. (2011). "Lady Huntingdon, religion and race". Methodist History. 50 (1): 28–40. hdl:10516/2867.

- Walsh, Robert; Littell, Eliakim; Smith, John Jay (1833). The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. E. Littell & T. Holden.

- Walsh, J. D. (1993). "Wesley vs. Whitefield". Christian History. 12 (2).

- Wesley, John (1774). Thoughts Upon Slavery. R. Hawes.

- White, Eryn M. (2011). "Whitefield, Wesley and Wales". Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society. 58 (3): 136–150.

- White, George (1855). Historical Collections of Georgia: Containing the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, Etc., Relating to Its History and Antiquities, from Its First Settlement to the Present Time; Compiled from Original Records and Official Documents; Illustrated by Nearly One Hundred Engravings. Pudney & Russell.

- Wiersbe, Warren W. (2009). 50 People Every Christian Should Know: Learning from Spiritual Giants of the Faith. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4412-0400-4.

- Witzig, Fred (2008). The Great Anti-Awakening: Anti-revivalism in Philadelphia and Charles Town, 1739–1745 (PhD). Indiana University. p. 138.

- Williams, Robert V. (1968), "George Whitefield's Bethesda: the Orphanage, the College, and the Library" (PDF), Proceedings of the Library History Seminar, no. 3, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022

- Yrigoyen, Charles; Daugherty, Ruth A. (1999). John Wesley: Holiness of Heart and Life. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-05686-6.

Primary sources[edit]

- Franklin, Benjamin (October 2008), The Autobiography, Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, ISBN 978-1-55709-079-9.

- Whitefield, George (1853), Gillies, John (ed.), Memoirs of the Rev. George Whitefield: to which is appended an extensive collection of his sermons and other writings, E. Hunt.

- Whitefield, George. Journals. London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1978. ISBN 978-0-85151-147-4

- ——— (2001), The Works (compilation), Weston Rhyn: Quinta Press, ISBN 978-1-897856-09-3.

- ——— (2010), Lee, Gatiss (ed.), The Sermons, Church society, ISBN 978-0-85190-084-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, John H. Five Great Evangelists: Preachers of Real Revival. Fearn (maybe Hill of Fearn), Tain: Christian Focus Publications, 1997. ISBN 978-1-85792-157-1

- Bormann, Ernest G (1985), Force of Fantasy: Restoring the American Dream, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, ISBN 978-0-8093-2369-2.

- Dallimore, Arnold A. George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival (Volume I). Edinburgh or Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust, 1970. ISBN 978-0-85151-026-2.

- Gibson, William and Morgan-Guy, John (eds), George Whitefield Tercentenary Essays. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2015 ISBN 9781783168330

- Johnston, E.A. George Whitefield: A Definitive Biography (2 volumes). Stoke-on-Trent: Tentmaker Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-1-901670-76-9.

- Hammond, Geordan and Jones, David Ceri(eds), George Whitefield: Life, Context, and Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19874-707-9.

- Kenney, William Howland, III. ″Alexander Garden and George Whitefield: The Significance of Revivalism in South Carolina 1738–1741″. The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 71, No. 1 (January 1970), pp. 1–16.

- Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-300-15846-5

- Lambert, Frank (1990). "Pedlar in Divinity': George Whitefield and the Great Awakening, 1737–1745". Journal of American History. 77 (3): 812–837. doi:10.2307/2078987. JSTOR 2078987.

- ——— (2011), The Accidental Revolutionary: George Whitefield and the Creation of America, Waco: Baylor University Press, ISBN 978-1-60258-391-7, archived from the original on 31 August 2013, retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Mansfield, Stephen. Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing (acquired by Sourcebooks), 2001. ISBN 978-1-58182-165-9

- Noll, Mark A (2010), The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys, InterVarsity Press, ISBN 978-0830838912.

- Philip, Robert. The Life and Times of George Whitefield. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 2007 (reprint) [1837]. ISBN 978-0-85151-960-9

- Pollock, John. George Whitefield and the Great Awakening. Hodder & Stoughton, 1973

- Reisinger, Ernest. The Founder's Journal, Issue 19/20, Winter/Spring 1995: "What Should We Think of Evangelism and Calvinism?" Archived 17 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Coral Gables: Founders Ministries.

- Schwenk, James L. Catholic Spirit: Wesley, Whitefield, and the Quest for Evangelical Unity in Eighteenth Century British Methodism (Scarecrow Press, 2008).

- Smith, Timothy L. Whitefield and Wesley on the New Birth (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Francis Asbury Press of Zondervan Publishing House, 1986).

- Streater, David "Whitefield and the Revival" (Crossway, Autumn 1993. No. 50) Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Thompson, D. D. John Wesley and George Whitefield in Scotland: Or, the Influence of the Oxford Methodists on Scottish Religion (London: Blackwood and Sons, 1898).

External links[edit]

- Bust of Whitefield at Gloucester City Museum & Art Gallery.

- Biographies, Articles, and Books on Whitefield Archived 30 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lesson plan on George Whitefield and the First Great Awakening

- George Whitefield's Journals project – Project to publish a complete edition of Whitefield's Journals

- George Whitefield at Old South Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, Massachusetts

- George Whitefield preaches to 3000 in Stonehouse Gloucestershire

- Works by or about George Whitefield at Internet Archive

- Works by George Whitefield at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Open Library

- Gutenberg

- 1714 births

- 1770 deaths

- 18th-century English Anglican priests

- 18th-century English Christian theologians

- 18th-century evangelicals

- Alumni of Pembroke College, Oxford

- American evangelicals

- American Evangelical writers

- American proslavery activists

- Anglican writers

- Benjamin Franklin

- Burials in Massachusetts

- Calvinistic Methodists

- Christian revivalists

- English evangelicals

- English Anglican missionaries

- English Calvinist and Reformed Christians

- English evangelists

- English Methodist missionaries

- English sermon writers

- English Evangelical writers

- Evangelical Anglicans

- Evangelical Anglican clergy

- Founders of orphanages

- History of Methodism

- History of Methodism in the United States

- Methodist missionaries in Europe

- Methodist missionaries in the United States

- People educated at The Crypt School, Gloucester

- Clergy from Gloucester

- Protestant missionaries in Bermuda

- Protestant missionaries in England

- Protestant missionaries in Gibraltar

- Protestant missionaries in Ireland

- Protestant missionaries in Scotland

- Protestant missionaries in the Netherlands

- Protestant missionaries in Wales

- Whitfield County, Georgia

- 18th-century Anglican theologians

- British slave owners

- Slave owners from the Thirteen Colonies