Francis Skinner

Francis Skinner | |

|---|---|

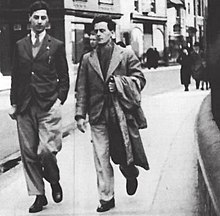

Francis Skinner (left) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (right) walking with one another in Cambridge | |

| Born | Sidney George Francis Guy Skinner 1912 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 11 October 1941 (aged 28–29)[1] |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | University of Cambridge (Graduated with a degree in mathematics in 1933) |

| Occupations | |

Sidney George Francis Guy Skinner (1912 – 11 October 1941) was a friend, collaborator, and lover of the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Biography[edit]

Francis Skinner was born in 1912 in Kensington, London, England.[1] Both his father and mother were academically distinguished: his father Sidney Skinner, was a Cambridge chemist and later Director of the South-Western Polytechnic Institute, and his mother, Marion Field Michaelis, a mathematician at Harvard College Observatory.[2]

Skinner was educated at St Paul's School in London.[3] He studied the Mathematics Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, following in the footsteps of his older sister Priscilla, herself a talented mathematician and an undergraduate at Newnham College.[3][4]

in 1930, Skinner, then a student, met Wittgenstein, fell under his influence and "became utterly, uncritically, and almost obsessively devoted" to him.[5] Their relationship was seen by others as being characterized by Skinner's eagerness to please Wittgenstein and conform to his opinions.

Skinner graduated with a first-class degree in mathematics from Cambridge in 1933 and was awarded a postgraduate fellowship.[3] He used this fellowship to work with Wittgenstein on a book on philosophy and mathematics (unpublished, possibly the "Pink Book" archive discovered in 2011).[6] While it has been assumed that Skinner was merely a student taking dictation, the discovery of the original archives indicates that Skinner played a significant role in shaping and editing the work.[1]

In 1934, the two made plans to emigrate to the Soviet Union and become manual labourers, but Wittgenstein visited the country briefly and realised the plan was not feasible; the Soviet Union might have allowed Wittgenstein to immigrate as a teacher, but not as a manual labourer.

During the academic year 1934–1935, Wittgenstein dictated to Skinner and Alice Ambrose the text of the Brown Book.[7]

Wittgenstein's hostility toward academia resulted in Skinner's withdrawal from university, first to become a gardener, and later a mechanic (much to the dismay of Skinner's family). Meanwhile, his sister Priscilla continued her mathematical career, winning a Fellowship and, during the Second World War, working as a mathematician at the Royal Aircraft Establishment. (Priscilla's daughter is chemist Ruth Lynden-Bell)

In the late 1930s, Wittgenstein grew increasingly distant from Skinner.

Skinner died from polio, following an air raid in Cambridge in October 1941, having been neglected during the rush to treat victims of the bombing.[1]

Despite the weakening of their relationship, Wittgenstein was apparently traumatised by Skinner's death, resulting in the loss for 7 years of the work they were engaged in together, the 'Pink Book'.[1]

Pink Book[edit]

In 2011, an extensive archive came to light, consisting of 170,000 words of handwriting, text and mathematics. This apparently had mostly been dictated by Wittgenstein to Skinner, with annotations by both. The archive includes a long-lost, so-called Pink Book. Wittgenstein had posted them to a friend of Skinner days after his death.[8]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Gibson, Arthur (2010). "The Wittgenstein Archive of Francis Skinner". In Nuno Venturinha (ed.), Wittgenstein After His Nachlass, pp. 64–77. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Cambridge Tribune, Volume XXIX, Number 8, 21 April 1906

- ^ a b c "University News", The Times, 16 June 1933, p. 19.

- ^ Newnham College Register, Vol 2, 1929

- ^ Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, p. 331

- ^ Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, p. 334

- ^ Wittgenstein L., The Blue and Brown Books, ed. by R. Rhees, London: Blackwell, 1958, preface p. v.

- ^ "Lost archive shows Wittgenstein in a new light". The Guardian. 26 April 2011.