Evolution: The Modern Synthesis

(publ. George Allen & Unwin)

Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, a popularising 1942 book by Julian Huxley (grandson of T.H. Huxley), set out his vision of the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology of the mid-20th century. It was enthusiastically reviewed in academic biology journals.[1][2][3][4]

Significance[edit]

In the book, Huxley tackles the subject of evolution at full length, in what became the defining work of his life. His role was that of a synthesiser rather than a researcher, and it helped that he had met many of the other participants. His book was written whilst he was Secretary to the Zoological Society of London, and made use of his remarkable collection of reprints covering the first part of the century. It was published in 1942.

Publication history[edit]

Allen & Unwin, London. (1942, reprinted 1943, 1944, 1945, 1948, 1955; 2nd ed, with new introduction and bibliography by the author, 1963; 3rd ed, with new introduction and bibliography by nine contributors, 1974). U.S. first edition by Harper, 1943.

Reception[edit]

Contemporaneous[edit]

Reviewing the book for American Scientist in 1943, the geologist Kirtley Mather wrote that the book provided "an admirable digest" of decades of work by many scientists. Mather commented "Of general interest is Huxley’s defense of the Darwinian concept of evolution, under attack by Hogben, Bateson and other biologists, amusingly reminiscent of bygone days when another Huxley championed the cause of evolution in a wholly different battle." Mather noted, too, that Huxley emphasises evolutionary progress, not by assuming that it means specialisation or "improvement" over earlier forms, but that attaining greater control over the environment and independence from it show man's progress at a new direction or rather at a higher level with "increases of aesthetic, intellectual, and spiritual experience and satisfaction."[5]

Modern[edit]

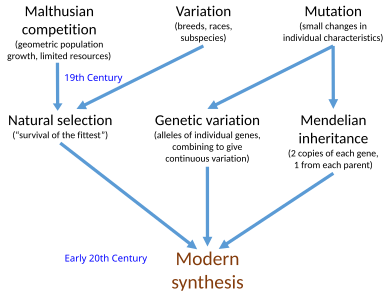

The historian and philosopher of science Ehud Lamm, on the book's reissue in 2010 for Darwin's bicentenary, writes that at almost 800 pages it was longer than the other "milestone" 1942 book on the modern synthesis, Ernst Mayr's Systematics and the Origin of Species. Lamm calls it remarkable that both books were described as popular accounts at the time, and notes that Huxley states in his introduction that he was setting out to promote a "synthetic point of view" on Darwinian evolution. Huxley was not just trying to synthesise natural selection with Mendelian genetics "as the Modern Synthesis is often presented", writes Lamm, but to include also "genetics, developmental physiology, ecology, systematics, paleontology, cytology [cell biology], and mathematical analysis." Lamm notes that the book was successful, with revised editions in 1963 and 1974, both of which added lengthy introductions that attempted to bring the book "at least partly up to date", given what Lamm and Huxley agreed were very large changes in the field. The 1942 text however was "a more tolerant, pluralistic, view of evolution than we have come to expect in the wake of the "hardening of the synthesis" (as Stephen Gould so aptly put it), with plenty of coverage of two "rebels", the discoverer of chromosomal crossover, Cyril Darlington, and the "avowedly anti-neoDarwinian" mutationist Richard Goldschmidt. Lamm notes that Goldschmidt's ideas on "genome-wide upheavals" may after all not be far wrong, given the epigenetic changes that can be caused by environmental stress. Huxley agreed with Darlington that hybridization and the polyploidy it could cause could result in increased variation and speciation. Lamm notes, too, that Huxley anticipated evolutionary developmental biology's attention to embryonic development for understanding evolution. Finally, the review observes that "It has long been debated whether the so-called Modern Synthesis was overall a positive force in biology, or whether its lacunae [gaps] undermine its contributions" and notes that people (such as Massimo Pigliucci) have called for a renewed synthesis, though biologists differ about its direction.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ Hubbs C.L. 1943. Evolution the new synthesis. American Naturalist 77, 365-68.

- ^ Kimball R.F. 1943. The great biological generalization. Quarterly Review of Biology 18, 364-67.

- ^ Karl P. Schmidt, Evolution the Modern Synthesis by Julian Huxley, Copeia, Vol. 1943, No. 4 (Dec. 31, 1943), pp. 262-263

- ^ Conway Zirkle, Isis, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Spring, 1944), pp. 192–194

- ^ Mather, Kirtley F. (April 1943). "Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, by Julian Huxley". American Scientist. 31 (2): 344. doi:10.1511/2012.97.344.

- ^ Lamm, Ehud. "Review of: Julian Huxley, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis – The Definitive Edition, with a new foreword by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd B. Müller. MIT Press" (PDF). Retrieved 21 August 2017.