Elinor Wylie

Elinor Wylie | |

|---|---|

Elinor Wylie | |

| Born | Elinor Morton Hoyt September 7, 1885 Somerville, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | December 16, 1928 (aged 43) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer, editor |

| Language | English |

| Notable works | Nets to Catch the Wind, Black Armor, Angels and Earthly Creatures |

| Notable awards | Julia Ellsworth Ford Prize |

| Spouse |

Philip Simmons Hichborn

(m. 1906; died 1912)Horace Wylie (m. 1916–19??) |

| Children | Philip Simmons Hichborn, Jr. |

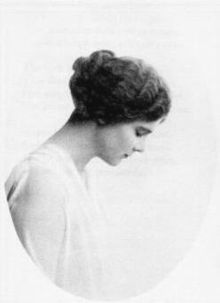

Elinor Morton Wylie (September 7, 1885 – December 16, 1928) was an American poet and novelist popular in the 1920s and 1930s. "She was famous during her life almost as much for her ethereal beauty and personality as for her melodious, sensuous poetry."[1]

Life[edit]

Family and childhood[edit]

Elinor Wylie was born Elinor Morton Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey, into a socially prominent family. Her grandfather, Henry M. Hoyt, was a governor of Pennsylvania. Her parents were Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr., who would be United States Solicitor General from 1903 to 1909; and Anne Morton McMichael (born July 31, 1861, in Pa.). Their other children were:

- Henry Martyn Hoyt III (1887–1920), an artist who married Alice Gordon Parker.

- Constance Hoyt (1889–1923) who married Ferdinand von Stumm-Halberg on March 30, 1910, in Washington, D.C.

- Morton McMichael Hoyt (1899-1949), three times married and divorced Eugenia Bankhead, known as "Sister" and sister of Tallulah Bankhead

- Nancy McMichael Hoyt (1902-1949), a romance novelist who wrote Elinor Wylie: The Portrait of an Unknown Woman (1935). She married Edward Davison Curtis; they divorced in 1932.

In 1887, the Hoyt family moved to Rosemont, a suburb of Philadelphia.[2]

Because of her father's political aspirations, Elinor spent much of her youth in Washington, DC.[3] She was educated at Miss Baldwin's School (1893–97), Mrs. Flint's School (1897–1901), and finally Holton-Arms School (1901–04).[4][failed verification] In particular, from age 12 to 20, she lived in Washington again where she made her debut in the midst of the "city's most prominent social élite,"[3] being "trained for the life of a debutante and a society wife".[5]

Marriages and scandal[edit]

The future Elinor Wylie became notorious, during her lifetime, for her multiple affairs and marriages. On the rebound from an earlier romance she met her first husband, Harvard graduate Philip Simmons Hichborn[5] (1882–1912), the son of a rear-admiral. She eloped with him and they were married on December 13, 1906, when she was 20. She had a son by him, Philip Simmons Hichborn, Jr., born September 22, 1907, in Washington, D.C. However, "Hichborn, a would-be poet, was emotionally unstable",[5] and Elinor found herself in an unhappy marriage.

She also found herself being stalked by Horace Wylie, "a Washington lawyer with a wife and three children", who "was 17 years older than Elinor. He stalked her for years, appearing wherever she was."[6]

Following the death in November 1910 of Elinor's father, and unable to secure a divorce from Hichborn,[3] she left her husband and son, and eloped with Wylie.

"After being ostracized by their families and friends and mistreated in the press, the couple moved to England"[7] where they lived "under the assumed name of Waring; this event caused a scandal in the Washington, D.C., social circles Elinor Wylie had frequented".[5] Philip Simmons Hichborn Sr. died by suicide in 1912.

With Horace Wylie's encouragement, in 1912 Elinor anonymously published Incidental Number, a small book of poems she had written in the previous decade.[5]

Between 1914 and 1916, Elinor tried to have a second child, but "suffered several miscarriages ... as well as a stillbirth and ... a premature child who died after one week."[5]

After Horace Wylie's wife agreed to a divorce, the couple returned to the United States and lived in three different states "under the stress of social ostracism and Elinor's illness." Elinor and Horace Wylie officially married in 1916, after Elinor's first husband had died by suicide and Horace's first wife had divorced him. By then, however, the couple were drawing apart."[5]

Elinor began spending time in literary circles in New York City—"her friends there numbered John Peale Bishop, Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis, Carl Van Vechten, and ... William Rose Benét."[5]

Her last marriage (in 1923)[8] was to William Rose Benét (February 2, 1886 – May 4, 1950), who was part of her literary circle and brother of Stephen Vincent Benét. By the time Wylie's third book of poetry, Trivial Breath in 1928 appeared, her marriage with Benét was also in trouble, and they had agreed to live apart. She moved to England and fell in love with the husband of a friend, Henry de Clifford Woodhouse, to whom she wrote a series of 19 sonnets which she published privately in 1928 as Angels and Earthly Creatures (also included in her 1929 book of the same name).[7]

Career[edit]

Elinor Wylie's literary friends encouraged her to submit her verse to Poetry magazine. Poetry published four of her poems, including what became "her most widely anthologized poem, 'Velvet Shoes'", in May 1920. With Benét now acting as her informal literary agent,[5] "Wylie left her second husband and moved to New York in 1921".[7] The Dictionary of Literary Biography (DLB) says: "She captivated the literary world with her slender, tawny-haired beauty, personal elegance, acid wit, and technical virtuosity."[5]

In 1921, Wylie's first commercial book of poetry, Nets to Catch the Wind, was published. The book, "which many critics still consider to contain her best poems," was an immediate success. Edna St. Vincent Millay and Louis Untermeyer praised the work.[5] The Poetry Society awarded her its Julia Ellsworth Ford Prize.[4]

In 1923 she published Black Armor, which was "another successful volume of verse".[5] The New York Times enthused: "There is not a misplaced word or cadence in it. There is not an extra syllable."[9]

1923 also saw the publication of Wylie's first novel, Jennifer Lorn, to considerable fanfare. Van Vechten "organized a torchlight parade through Manhattan to celebrate its publication".[5]

According to Carl Van Doren, Wylie had "as sure and strong an intelligence" as he has ever known. Her novels were "flowers with roots reaching down into unguessed deeps of erudition."[3]

She worked as the poetry editor of Vanity Fair magazine between 1923 and 1925. She was an editor of Literary Guild, and a contributing editor of The New Republic, from 1926 through 1928.[5]

Wylie was an "admirer of the British Romantic poets, and particularly of Shelley, to a degree that some critics have seen as abnormal".[5] She wrote a 1926 novel, The Orphan Angel, in which "the great young poet is rescued from drowning off an Italian cape and travels to America, where he encounters the dangers of the frontier."[5]

By the time of Wylie's third book of poetry, Trivial Breath in 1928, her marriage with Benét was also in trouble, and they had agreed to live apart. She moved to England and fell in love with the husband of a friend, Henry de Clifford Woodhouse, to whom she wrote a series of 19 sonnets which she published privately in 1928 as Angels and Earthly Creatures (also included in her 1929 book of the same name).[7]

Elinor Wylie's literary output is impressive, given that her writing career lasted just eight years. In that brief period, she crowded four volumes of poems, four novels, and enough magazine articles to "make up an additional volume."[3]

Death[edit]

Wylie suffered from very high blood pressure all her adult life. As a result, she was prone to unbearable migraines and died of a stroke at Benét's New York apartment at the age of 43. At the time, they were both preparing for publication her Angels and Earthly Creatures.[5]

Writing[edit]

Poetry[edit]

Wylie's "highly polished, articulate, and deeply emotional verse shows the influence of the metaphysical poets,"[1] such as John Donne, George Herbert, and Andrew Marvell. If her poetry is derivative of anyone, though, that would be "of the British Romantic poets, and particularly of Shelley," whom she admired "to a degree that some critics have seen as abnormal."[5]

In her first book, Nets to Catch the Wind, "Stanzas and lines were quite short, and the effect of her images was of a highly detailed, polished surface. Often, her poems expressed a dissatisfaction with the realities of life on the part of a speaker who aspired to a more gratifying world of art and beauty."[5] Louis Untermeyer wrote that the book "impresses immediately because of its brilliance ... which, at first, seems to sparkle without burning.... It is the brilliance of moon-light corruscating on a plain of ice. But if Mis. Wylie seldom allows her verses to grow agitated, she never permits them to remain dull.... in 'August' the sense of heat is conveyed by tropic luxuriance and contrast; in 'The Eagle and the Mole' she lifts didacticism to a proud level ... never has snow-silence been more unerringly communicated than in 'Velvet Shoes.'"[10] Other notable poems include "Wild Peaches," "A Proud Lady," "Sanctuary," "Winter Sleep," "Madman's Song," "The Church-Bell," and "A Crowded Trolley Car."

In Black Armor (1923), "the intellect has grown more fiery, the mood has grown warmer, and the craftsmanship is more dazzling than ever.... she varies the perfect modulation with rhymes that are delightfully acrid and unique departures which never fail of success ... from the nimble dexterity of a rondo like 'Peregrine' to the introspective poignance of 'Self Portrait,' from the fanciful 'Escape' to the grave mockery of 'Let No Charitable Hope.'"[10]

Trivial Breath (1928) "is the work of a poet in transition. At times the craftsman is uppermost; at times the creative genius."[10]

Wylie's biographer Stanley Olson called the sonnets that begin 1929's Angels and Earthly Creatures "perhaps, her finest achievement.... The love in these lyrics is not a private love, not a variety of confession, but an abstracted one.... The nineteen sonnets are paced with strength, energy and undeniable feeling, sustained as a group by shifting through the complexities and vicissitudes of love."[5] Untermeyer also praised the sonnets, but added: "The other poems share this intensity. 'This Corruptible' is both visionary and philosophic; 'O Virtuous Light' deals with that piercing clarity, the intuition ... The other poems are scarcely less uplifted, finding their summit in 'Hymn to Earth, which is one of her deeper poems and one which is certain to endure."[10]

Fiction[edit]

Wylie's four novels "are delicately wrought and filled with ironic fancy".[1]

Cultural references[edit]

Bram Stoker dedicated his 1903 novel The Jewel of Seven Stars to Wylie and her sister Constance, whom he had met when they were visiting London.[11]

The title of Tennessee Williams' play, In Masks Outrageous and Austere, is taken from the last stanza of Wylie's poem "Let No Charitable Hope:" "In masks outrageous and austere / The years go by in single file; / But none has merited my fear, / And none has quite escaped my smile."

Publications[edit]

Poetry[edit]

- [Anonymous], Incidental Numbers. London: private, 1912.

- Nets to Catch the Wind. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1921.

- Black Armour. New York: Doran, 1923.

- Trivial Breath. New York, London: Knopf, 1928.

- Angels and Earthly Creatures: A Sequence of Sonnets Henley on Thames, UK: Borough Press, 1928. (also known as One Person).

- Angels and Earthly Creatures. New York, London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1929. (includes Angels and Earthly Creatures: A Sequence of Sonnets).

- Birthday Sonnet. New York: Random House, 1929.

- Collected Poems of Elinor Wylie. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1932.

- Last Poems of Elinor Wylie, transcribed by Jane D. Wise, foreword by William Rose Benet, tribute by Edith Olivier. New York: Knopf, 1943. Chicago: Academy, 1982.

- Selected Works of Elinor Wylie. Evelyn Helmick Hively ed. Kent State U Press, 2005.

Velvet Shoes, Gutenburg Project

Novels[edit]

- Jennifer Lorn: A Sedate Extravaganza. New York: Doran, 1923. London: Richards, 1924.

- The Venetian Glass Nephew. New York: Doran, 1925. Chicago: Academy, 1984.

- The Orphan Angel. New York: Knopf, 1926. Also published as Mortal Image. London: Heinemann, 1927.

- Mr. Hodge & Mr. Hazard. New York. Knopf, 1928. London: Heinemann, 1928. Chicago: Academy, 1984.

- Collected Prose of Elinor Wylie. New York: Knopf, 1933.

Personal papers[edit]

- Her personal papers reside in the Elinor Wylie Archive, Beinecke Rare Book Room and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and in the Berg Collection, New York Public Library.[12]

References[edit]

- Olson, Stanley. Elinor Wylie: A Biography. New York: Dial, 1979.

- Hively, Evelyn Helmick. "Elinor Wylie," Twentieth Century Criticism. Vol 8. Detroit: Gale Research, 1982.

- Hively, Evelyn Helmick. A Private Madness: The Genius of Elinor Wylie. Kent State U P, 2003.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c " Wylie, Elinor (Hoyt)," InfoPlease.com, Web, Apr. 7, 2011

- ^ "A Guide to the Papers of Elinor Wylie, 1921-1928". Archived from the original on 2019-10-24. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Moroney, Claribel A. (1947). An Investigation of the "Fragile Escape in the Work of Elinor Wylie (Masters Thesis). Chicago: Loyola University.

- ^ a b "Selected Poetry of Elinor Wylie: Notes on Life and Works Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine," Representative Poetry Online, UToronto.ca, Web, Apr. 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Elinor Wylie 1885-1928," Poetry Foundation, Web, Apr. 7, 2011.

- ^ Elinor Wylie, AllPoetry.com, March 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Elinor Wylie 1885-1928," eNotes.com, Web, Apr. 7, 2011

- ^ New International Encyclopedia

- ^ "“Some Rhymesters ‘Piping Strains the World at Last Shall Heed,’” New York Times, 10 June 1923. Quoted in "Elinor Wylie Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine," Intimate Circles: American Women In the Arts, Yale.edu, Web, Apr. 7, 2011,

- ^ a b c d Louis Untermeyer, Elinor Wylie,'" Modern American Poetry, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1930), 538-540.

- ^ Stoker, Bram (31 July 2008). The Jewel of Seven Stars (Penguin Classics ed.). Penguin Classics. p. 252. ISBN 9780141442211.

- ^ "Elinor Wylie: Bibliography," The Poetry Foundation, Web, Aug. 6, 2011.

External links[edit]

- Elinor Wylie at the Poetry Foundation - Biography and 8 poems (A Crowded Trolley Car, Cold Blooded Creatures, Epitaph, Full Moon, Little Elegy, Speed the Parting, Valentine, Wild Peaches)

- Works by Elinor Wylie at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Elinor Wylie at Internet Archive

- Works by Elinor Wylie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Poems of Elinor Wylie at Poemtree.com

- Poems of Elinor Wylie at Poets' Corner

- Elinor Wylie at Library of Congress, with 43 library catalog records

- A Guide to the Papers of Elinor Wylie, 1921-1928, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia