Dig Dug

| Dig Dug | |

|---|---|

Advertising flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Namco |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Masahisa Ikegami[4] Shigeru Yokoyama[5] |

| Programmer(s) | Shouichi Fukatani Toshio Sakai[4] |

| Artist(s) | Hiroshi Ono[6] |

| Composer(s) | Yuriko Keino |

| Series | Dig Dug |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Atari 2600, Atari 5200, ColecoVision, Commodore 64, Apple II, PV-1000, LCD, MSX, NES, Atari 7800, Atari 8-bit, X68000, Game Boy, Mobile phone, Game Boy Advance, iOS, Xbox 360 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Maze |

| Mode(s) | 1-2 players alternating turns |

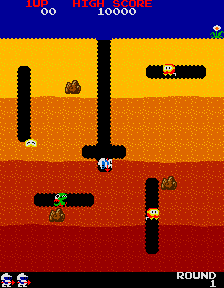

Dig Dug[a] is a maze arcade video game developed by Namco in 1981 and released in 1982, distributed in North America by Atari, Inc. The player controls Dig Dug to defeat all enemies per stage, by either inflating them to bursting or crushing them underneath rocks.

Dig Dug was planned and designed by Masahisa Ikegami, with help from Galaga creator Shigeru Yokoyama. It was programmed for the Namco Galaga arcade board by Shouichi Fukatani, who worked on many of Namco's earlier arcade games, along with Toshio Sakai. Music was composed by Yuriko Keino, including the character movement jingle at executives' request, as her first Namco game. Namco heavily marketed it as a "strategic digging game".

Upon release, Dig Dug was well received by critics for its addictive gameplay, cute characters, and strategy. During the golden age of arcade video games, it was globally successful, including as the second highest-grossing arcade game of 1982 in Japan. It prompted a long series of sequels and spin-offs, including the Mr. Driller series, for several platforms. It is in many Namco video game compilations for many systems.

Gameplay[edit]

Dig Dug is a maze video game. The player controls protagonist Dig Dug (Taizo Hori) to eliminate each screen's enemies: Pookas, red creatures with comically large goggles; and Fygars, fire-breathing green dragons. Dig Dug can use an air pump to inflate them to bursting or crush them under large falling rocks. Bonus points are awarded for squashing multiple enemies with a single rock, and dropping two rocks in a stage yields a bonus item, which can be eaten for points. Once all the enemies have been defeated, Dig Dug progresses to the next stage.[7]

Enemies chase Dig Dug through dirt in the form of ghostly eyes, only becoming solid in the air where his pump can stun or destroy them. Enemies eventually become faster and more aggressive and the last one then attempts escape. Later stages vary in dirt color, while increasing the number and speed of enemies.[7]

The game has 256 stages in all.

Development[edit]

In 1981, Dig Dug was planned and designed by Masahisa Ikegami,[4] with help from Shigeru Yokoyama, the creator of Galaga.[5] The game was programmed for the Namco Galaga arcade system board by Shigeichi Ishimura, a Namco hardware engineer, and the late Shouichi Fukatani,[8] along with Toshio Sakai.[4] Other staff members were primarily colleagues of Shigeru Yokoyama.[5] Yuriko Keino composed the soundtrack, as her first video game project. Tasked with making Dig Dug's movement sound, she could not make a realistic stepping sound, so she instead made a short melody.[9] Hiroshi "Mr. Dotman" Ono, a Namco graphic artist, designed the sprites.

The team hoped to allow player-designed mazes which could prompt unique gameplay mechanics, contrasting with the pre-set maze exploration in Pac-Man (1980). Namco's marketing materials heavily call it a "strategic digging game".[10]

Release[edit]

Dig Dug was released in 1982, in Japan on February 20,[1] in North America in April by Atari (as part of the licensing deal with Namco),[11][12] and in Europe on April 19 by Namco.[2]

The first home conversion of Dig Dug was released for the Atari 2600 in 1983, developed and published by Atari, which was followed by versions for the Atari 5200, Atari 8-bit family, Commodore 64, and Apple II. In Japan, it was ported to the Casio PV-1000 in 1983, the MSX in 1984, and the Famicom in 1985. Gakken produced a handheld LCD tabletop game in 1983, which replaced Dig Dug's air pump with a flamethrower to accommodate hardware limitations. Namco released a Game Boy conversion in North America only in 1992, with an all-new game called "New Dig Dug" where the player must collect keys to open an exit door; this version was later included in the 1996 Japan-only compilation Namco Gallery Vol. 2, which also includes Galaxian, The Tower of Druaga, and Famista 4.[13] A Japanese X68000 version was developed by Dempa and released in 1995, bundled with Dig Dug II.[14] The Famicom version was re-released in Japan for the Game Boy Advance in 2004 as part of the Famicom Mini series.[13]

Dig Dug is a mainstay in Namco video game compilations, including Namco Museum Vol. 3 (1996), Namco History Vol. 3 (1998), Namco Museum 64 (1999),[15] Namco Museum 50th Anniversary (2005),[16] Namco Museum Remix (2007),[17] Namco Museum Essentials (2009),[18] and Namco Museum Switch (2017).[19] The game was released online on Xbox Live Arcade in 2006, supporting online leaderboards and achievements.[20] It is part of Namco Museum Virtual Arcade, and was added to the Xbox One's backward compatibility lineup in 2016.[21] A version for the Japanese Wii Virtual Console was released in 2009.[22] Dig Dug is a bonus game in Pac-Man Party, alongside the arcade versions of Pac-Man and Galaga.[23]

Reception[edit]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Eurogamer | 8/10 (Arcade)[26] 6/10 (XBLA)[27] |

| GameSpot | 6/10 (XBLA)[28] |

| IGN | 7/10 (XBLA)[20] |

| Computer Games | A (Atari 5200)[29] |

| Electronic Fun |

Dig Dug was a critical and commercial success upon release, and was praised for its gameplay and layered strategy.[26] In Japan, it was the second highest-grossing arcade game of 1982, just below Namco's Pole Position.[31] In North America, Atari sold 22,228 Dig Dug arcade cabinets by the end of 1982, earning $46,300,000 (equivalent to $146,000,000 in 2023) in cabinet sales.[32] Around July 1983, it was one of the six top-grossing games.[33] It was popular during the golden age of arcade video games. The 2004 Famicom Mini release had 58,572 copies sold,[34] and the Xbox Live Arcade version had 222,240 copies by 2011.[35]

American publication Blip Magazine favorably compared it to games such as Pac-Man for its simple controls and fun gameplay.[36] Allgame called it "an arcade and NES classic", praising its characters, gameplay, and unique premise, and for its easy home platform conversion.[25] In 1998, Japanese magazine Gamest called it one of the greatest arcade games of all time for its addictiveness and for breaking the traditional "dot-eater" gameplay used in games such as Pac-Man and Rally-X.[37] In a 2007 retrospective, Eurogamer praised its "perfect" gameplay and strategy, saying it is one of "the most memorable and legendary videogame releases of the past 30 years".[26] The Killer List of Videogames rated it the sixth most popular coin-op game of all time.[38]

Electronic Fun with Computers & Games praised the Atari 8-bit version for retaining the arcade's entertaining gameplay and for its simple controls.[30]

Some home versions were criticized for quality and lack of exclusive content. Readers of Softline magazine ranked Dig Dug the tenth-worst Apple II and fourth-worst Atari 8-bit video game of 1983 for its subpar quality and failure of consumer expectations.[39]

Reviewing the Xbox Live Arcade digital re-release, IGN liked its presentation, leaderboards, and addictive gameplay, recommending it for old and new fans alike.[20] A similar response was echoed by GameSpot for its colorful artwork and faithful arcade gameplay,[28] and by Eurogamer for addictiveness and longevity.[27] Eurogamer, IGN, and GameSpot all criticized its lack of online multiplayer and for achievements being too easy to unlock,[20][28] with Eurogamer in particular criticizing the game's controls for sometimes being unresponsive.[27]

Legacy[edit]

Dig Dug prompted a fad of "digging games".[40] Clones include the arcade game Zig Zag (1982),[41] the Atari 8-bit family game Anteater (1982) by Romox, Merlin's Pixie Pete, Victory's Cave Kooks (1983) for the Commodore 64, and Saguaro's Pumpman (1984) for the TRS-80 Color Computer.[42] The most successful is Universal Entertainment's arcade game Mr. Do! (1982), released about six months later and surpassing clone status.[40] Sega's Borderline (1981), when it was ported to the Atari 2600 as Thunderground in 1983,[43] was mistaken as a "semi-clone" of Dig Dug and Mr. Do![44] Boulder Dash (1984) also drew comparisons to Dig Dug.[45][46] Numerous mobile games are clones or variations of Dig Dug, such as Diggerman, Dig Deep, Digby Forever, Dig Out, Puzzle to the Center of Earth, Mine Blitz, I Dig It, Doug Dug, Minesweeper, Dig a Way, and Dig Dog.[47]

Sequels[edit]

Dig Dug prompted a long series of sequels for several platforms. The first of these, Dig Dug II, was released in Japan in 1985 to less success,[48] opting for an overhead perspective; instead of digging through earth, Dig Dug drills along fault lines to sink pieces of an island into the ocean.[49] A second sequel, Dig Dug Arrangement, was released for arcades in 1996 as part of the Namco Classic Collection Vol. 2 arcade collection,[50] with new enemies, music, power-ups, boss fights, and two-player co-operative play.

A 3D remake of the original, Dig Dug Deeper, was published by Infogrames in 2001 for Windows.[51] A Nintendo DS sequel, Dig Dug: Digging Strike, was released in 2005, combining elements from the first two games and adding a narrative link to the Mr. Driller series.[52] A massively-multiplayer online game, Dig Dug Island, was released in 2008, and was an online version of Dig Dug II;[53] servers lasted for less than a year, discontinued on April 21, 2009.[54]

Related media[edit]

Two Dig Dug-themed slot machines were produced by Japanese company Oizumi in 2003, both with small LCD monitors for animated characters.[55][56] A webcomic adaptation was produced in 2012 by ShiftyLook, a subsidiary of Bandai Namco focused on reviving older Namco franchises, with nearly 200 issues by several different artists, concluding in 2014 following the closure of ShiftyLook. Dig Dug is a main character in the ShiftyLook webseries Mappy: The Beat. A remix of the Dig Dug soundtrack appears in the PlayStation 2 game Technic Beat.[13]

The character Dig Dug was renamed to Taizo Hori, a play on the Japanese phrase "horitai zo", meaning "I want to dig". He became a prominent character in Namco's own Mr. Driller series, where he is revealed to be the father of Susumu Hori and being married to Baraduke protagonist Masuyo Tobi, who would divorce for unknown reasons. Taizo appears as a playable character in Namco Super Wars for the WonderSwan Color and Namco × Capcom for the PlayStation 2, only in Japan.[13][57] Taizo appears in the now-defunct web browser game Namco High as the principal of the high school, simply known as "President Dig Dug". Pookas appear in several Namco games, including Sky Kid (1985), R4: Ridge Racer Type 4 (1998),[13] Pac-Man World (1999),[13] Pro Baseball: Famista DS 2011 (2011), and in Nintendo's Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U (2014). Dig Dug characters briefly appear in the film Wreck-It Ralph (2012).[13]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Dig Dug (Registration Number PA0000133618)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Retrodiary: 1 April – 28 April". Retro Gamer. No. 88. Bournemouth, England. April 2011. p. 17. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ "Video Game Flyers: Dig Dug, Namco (Germany)". The Arcade Flyer Archive. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Szczepaniak, John (November 2015). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. Vol. 2 (First ed.). S.M.G Szczepaniak. p. 201. ISBN 978-1518818745.

- ^ a b c Namco Bandai Games (2011). "Galaga - 30th Anniversary Developer Interview". Galaga WEB. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Kiya, Andrew (October 17, 2021). "Former Namco Pixel Artist Hiroshi 'Mr. Dotman' Ono Has Died". Siliconera. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Dig Dug instruction manual (FC) (PDF). Namco. 1985. p. 9.

- ^ Szczepaniak, John (August 11, 2014). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers (First ed.). SMG Szczepaniak. p. 363. ISBN 978-0992926007. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ "『ディグダグ』の音楽はBGMでなく歩行音。慶野由利子さんが語る80年代ナムコのゲームサウンド(動画あり)- ライブドアニュース". Livedoor News (in Japanese). August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "OLD ゲーム - ディグダグ". Gamest. November 1986. p. 58. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ Akagi, Masumi (October 13, 2006). アーケードTVゲームリスト国内•海外編(1971-2005) [Arcade TV Game List: Domestic • Overseas Edition (1971-2005)] (in Japanese). Japan: Amusement News Agency. p. 111. ISBN 978-4990251215.

- ^ "Manufacturers Equipment". Cash Box. United States. February 5, 1983. p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kalata, Kurt (December 3, 2008). "Dig Dug". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Masuda, Atsushi. "『ディグダグ』 パソコン版とアーケード版の"差"に増田少年愕然!". AKIBA PC-Watch. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Fielder, Joe (April 28, 2000). "Namco Museum 64 Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Aaron, Sean (September 3, 2009). "Namco Museum: 50th Anniversary Review (GCN)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Aaron, Sean (July 12, 2009). "Namco Museum Remix Review (Wii)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Roper, Chris (July 21, 2009). "Namco Museum Essentials Review". IGN. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Whitehead, Thomas (June 29, 2017). "Bandai Namco Confirms July Release for Namco Museum on Nintendo Switch". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on December 28, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Brudvig, Erik (October 11, 2006). "Dig Dug Review". IGN. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ "Another Five Games Bring Weekly Xbox One Backward Compatibility Total To Ten". www.GameInformer.com. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Side-BN issue 53 (PDF). Namco Bandai Games, Inc. November 5, 2009. p. 21.

- ^ Hernandez, Pedro. "Pac-Man Party Review". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Weiss, Brett Alan. "Dig Dug - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Baize, Anthony. "Dig Dug - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c McFerran, Damien (October 25, 2007). "Dig Dug". Eurogamer. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c Reed, Kristan (October 16, 2006). "Dig Dug". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c Davis, Ryan. "Dig Dug Review". GameSpot. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ Dimetrosky, Ray (April 1984). "Reviews: Video Game Buyer's Guide". Computer Games. Vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 60–2.

- ^ a b Ardai, Charles (March 1984). "Dig Dug". No. 5. Fun & Games Publishing. Electronic Fun with Computers & Games. p. 54. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ ""Pole Position" No. 1 Video Game: Game Machine's "The Year's Best Three AM Machines" Survey Results" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 207. Amusement Press, Inc. March 1, 1983. p. 30.

- ^ "Atari Production Numbers Memo". Atari Games. January 4, 2010. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Fujihara, Mary (July 25, 1983). "Inter Office Memo: Coin-Op Product Sales" (PDF). Atari, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Game Search (based on Famitsu data)". Game Data Library. March 1, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Langley, Ryan (January 20, 2012). "Xbox Live Arcade by the numbers - the 2011 year in review". Gamasutra. UBM Technology Group. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Dig Dug". No. 1. Blip Magazine. February 1983. pp. 18–19. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ "「ザ・ベストゲーム」". GAMEST MOOK Vol.112 ザ・ベストゲーム2 アーケードビデオゲーム26年の歴史 (Vol. 5, Issue 4 ed.). Gamest. January 17, 1998. p. 89. ISBN 9784881994290.

- ^ McLemore, Greg. "The Top Coin-Operated Videogames of All Time". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ "The Best and the Rest" (PDF). St.Game. March–April 1984. p. 49. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Hawken, Kieren (December 3, 2019). The A-Z of Arcade Games: Volume 1. Andrews UK Limited. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-78982-193-2.

- ^ Kalata, Kurt. "Hardcore Gaming 101: Dig Dug". GameSpy. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Hague, James (April 13, 2021). "The Giant List of Classic Game Programmers". Dadgum. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ Marley, Scott (December 2016). "SG-1000". Retro Gamer. No. 163. p. 58.

- ^ Meade, E.C.; Clark, Jim (December 1983). "Thunderground (Sega for the 2600)". Videogaming Illustrated. p. 14.

- ^ "1985 Software Buyer's Guide". Computer Games. Vol. 3, no. 5. United States: Carnegie Publications. February 1985. p. 11.

- ^ Fox, Matt (January 3, 2013). The Video Games Guide: 1,000+ Arcade, Console and Computer Games, 1962-2012, 2d ed. McFarland & Company. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7864-7257-4.

- ^ Sheridan, Trevor. "Can You Dig It In These Arcade Digging Games?". NowGaming. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ All About Namco. Radio News Company. 1985. p. 81.

- ^ "Dig Dug II - Videogame by Namco". Killer List of Video Games. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "Namco Classic Collection Vol. 2". Killer List of Video Games. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "Dig Dug Deeper". December 14, 2001. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Nours Vol. 50 (PDF). Namco. September 10, 2005. p. 20. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "「ディグダグアイランド」,クオカードやホランが当たるキャンペーン". 4Gamer. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- ^ "ベルクス,「ディグダグアイランド」と「タンくる」のサービス終了を決定". 4Gamer. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ "ディグダグZ". P-World. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "ディグダグ". P-World. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ ナムコ クロス カプコン - キャラクター (in Japanese). Namco × Capcom Website. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

External links[edit]

- Dig Dug at MobyGames

- Dig Dug at the Killer List of Videogames

- 1982 video games

- Arcade video games

- Apple II games

- Atari arcade games

- Atari 2600 games

- Atari 5200 games

- Atari 7800 games

- Atari 8-bit family games

- Bandai Namco Entertainment franchises

- ColecoVision games

- Commodore 64 games

- VIC-20 games

- Famicom Disk System games

- Game Boy games

- Intellivision games

- IOS games

- Namco arcade games

- Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Nintendo Switch games

- Mobile games

- MSX games

- PlayStation 4 games

- X68000 games

- TI-99/4A games

- Video games developed in Japan

- Video games scored by Yuriko Keino

- Virtual Console games

- Virtual Console games for Wii U

- Xbox 360 Live Arcade games

- Maze games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Arcade Archives games

- Hamster Corporation games

- Multiplayer hotseat games