Dick Clark

Dick Clark | |

|---|---|

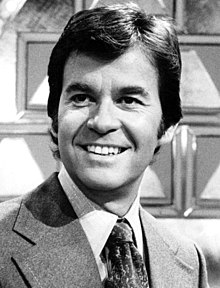

Clark in 1974 | |

| Born | Richard Wagstaff Clark November 30, 1929 Bronxville, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 18, 2012 (aged 82) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Syracuse University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1945–2012 |

| Organization | Dick Clark Productions |

| Known for | American Bandstand Pyramid Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve |

| Spouses | Barbara Mallery

(m. 1952; div. 1961)Loretta Martin

(m. 1962; div. 1971)Kari Wigton (m. 1977) |

| Children | 3, including Duane |

| Awards | Full list |

Richard Wagstaff Clark[1][2] (November 30, 1929 – April 18, 2012) was an American television and radio personality and television producer who hosted American Bandstand from 1956 to 1989. He also hosted five incarnations of the Pyramid game show from 1973 to 1988 and Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve, which broadcast New Year's Eve celebrations in New York City's Times Square.

As host of American Bandstand, Clark introduced rock and roll to many Americans. The show gave many new music artists their first exposure to national audiences, including Ike & Tina Turner, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Stevie Wonder, Simon & Garfunkel, Iggy Pop, Prince, Talking Heads, and Madonna. Episodes he hosted were among the first in which black people and white people performed on the same stage, and they were among the first in which the live studio audience sat down together without racial segregation. Singer Paul Anka claimed that Bandstand was responsible for creating a "youth culture". Due to his perennially youthful appearance and his largely teenaged audience of American Bandstand, Clark was often referred to as "America's oldest teenager" or "the world's oldest teenager".[3][4]

In his off-stage roles, Clark served as chief executive officer of Dick Clark Productions company (though he sold his financial interest in the company during his later years). He also founded the American Bandstand Diner, a restaurant chain themed after the television program of the same name. In 1973, he created and produced the annual American Music Awards show, similar to the Grammy Awards.[3]

Early life[edit]

Clark was born in Bronxville, New York, and raised in neighboring Mount Vernon,[5] the second child of Richard Augustus Clark and Julia Fuller Clark, née Barnard. His only sibling, elder brother Bradley, a World War II P-47 Thunderbolt pilot, was killed in the Battle of the Bulge.[6]

Clark attended Mount Vernon's A.B. Davis High School (later renamed A.B. Davis Middle School), where he was an average student.[7] At the age of 10, Clark decided to pursue a career in radio.[7] In pursuit of that goal, he attended Syracuse University, graduating in 1951 with a degree in advertising and a minor in radio.[7] While at Syracuse, he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Phi Gamma).[8]

Radio and television career[edit]

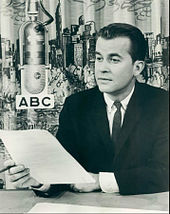

In 1945, Clark began his career working in the mailroom at WRUN, an AM radio station in Utica, New York, that was owned by his uncle and managed by his father. Almost immediately, he was asked to fill in for the vacationing weatherman and, within a few months, he was announcing station breaks.[7]

While attending Syracuse, Clark worked at WOLF-AM, then a country music station. After graduation, he returned to WRUN for a short time where he went by the name Dick Clay.[7] After that, Clark got a job at the television station WKTV in Utica, New York.[7] His first television-hosting job was on Cactus Dick and the Santa Fe Riders, a country-music program. He later replaced Robert Earle (who later hosted the GE College Bowl) as a newscaster.[9]

In addition to his announcing duties on radio and television, Clark owned several radio stations. From 1964 to 1978, he owned KPRO (now KFOO) in Riverside, California under the name Progress Broadcasting.[10][11] In 1967, he purchased KGUD-AM-FM (now KTMS and KTYD respectively) in Santa Barbara, California.[12][13]

American Bandstand[edit]

In 1952, Clark moved to Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia, where he took a job as a disc jockey at radio station WFIL, adopting the Dick Clark handle.[14] WFIL had an affiliated television station (now WPVI) with the same call sign, which began broadcasting a show called Bob Horn's Bandstand in 1952. Clark was responsible for a similar program on the company's radio station and served as a regular substitute host when Horn went on vacation.[7] In 1956, Horn was arrested for drunk driving and was subsequently dismissed.[7] On July 9, 1956, Clark became the show's permanent host.[7]

Bandstand was picked up by the ABC television network, renamed American Bandstand, and debuted nationally on August 5, 1957.[15] The show took off, due to Clark's natural rapport with the live teenage audience and dancing participants as well as the "clean-cut, non-threatening image" he projected to television audiences.[16] As a result, many parents were introduced to rock and roll music. According to Hollywood producer Michael Uslan, "he was able to use his unparalleled communication skills to present rock 'n roll in a way that was palatable to parents."[17] James Sullivan of Rolling Stone stated that "Without Clark, rock & roll in its infancy would have struggled mightily to escape the common perception that it was just a passing fancy."[18]

In 1958, The Dick Clark Show was added to ABC's Saturday night lineup.[7] By the end of year, viewership exceeded 20 million, and featured artists were "virtually guaranteed" large sales boosts after appearing.[7] In a surprise television tribute to Clark in 1959 on This Is Your Life, host Ralph Edwards called him "America's youngest starmaker", and estimated the show had an audience of 50 million.

Clark moved the show from Philadelphia to Los Angeles in 1964.[7] The move was related to the popularity of new "surf" groups based in southern California, including The Beach Boys and Jan and Dean. After moving to Los Angeles, the show became more diverse and featured more minorities.[19] The show was notable for promoting desegregation in popular music and entertainment by prominently featuring black musicians and dancers.[20][18] Prior to this point, the show had largely excluded black teenagers.[21][22]

The show ran daily Monday through Friday until 1963, then weekly on Saturdays until 1988. Bandstand was briefly revived in 1989, with David Hirsch taking over hosting duties. By the time of its cancellation, the show had become the longest-running variety show in TV history.[7]

In the 1960s, the show's emphasis changed from merely playing records to including live performers. During this period, many of the leading rock bands and artists of the 1960s had their first exposure to nationwide audiences. A few of the many artists introduced were Ike and Tina Turner, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, The Beach Boys, Stevie Wonder, Prince, Simon and Garfunkel, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Bobby Fuller, Johnny Cash, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino and Chubby Checker.[23][24]

During an interview with Clark by Henry Schipper of Rolling Stone magazine in 1990, it was noted that "over two-thirds of the people who've been initiated into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame had their television debuts on American Bandstand, and the rest of them probably debuted on other shows [they] produced."[25] During the show's lifetime, it featured over 10,000 live performances, many by artists who were unable to appear anywhere else on TV, as the variety shows during much of this period were "antirock".[25] Schipper points out that Clark's performers were shocking to general audiences:

The music establishment, and the adults in general, really hated rock and roll. Politicians, ministers, older songwriters and musicians foamed at the mouth. Frank Sinatra reportedly called Elvis Presley a "rancid-smelling aphrodisiac".[25]

Clark was therefore considered to have a negative influence on youth and was well aware of that impression held by most adults:

I was roundly criticized for being in and around rock and roll music at its inception. It was the devil's music, it would make your teeth fall out and your hair turn blue, whatever the hell. You get through that.[26]

In 2002, many of the bands he introduced appeared at the 50th anniversary special to celebrate American Bandstand.[27] Clark noted during the special that American Bandstand was listed in the Guinness Book of Records as "the longest-running variety show in TV history." In 2010, American Bandstand and Clark himself were honored at the Daytime Emmy Awards.[28] Hank Ballard, who wrote "The Twist", described Clark's popularity during the early years of American Bandstand:

The man was big. He was the biggest thing in America at that time. He was bigger than the president![29]

As a result of Clark's work on Bandstand, journalist Ann Oldenburg states "he deserves credit for doing something bigger than just putting on a show."[29] Los Angeles Times writer Geoff Boucher goes further, stating that "with the exception of Elvis Presley, Clark was considered by many to be the person most responsible for the bonfire spread of rock 'n roll across the country in the late 1950s", making Clark a "household name".[17] He became a "primary force in legitimizing rock 'n' roll", adds Uslan. Clark, however, simplified his contribution:

I played records, the kids danced, and America watched.[30]

Shortly after becoming its host, Clark also ended the show's all-white policy by featuring black artists such as Chuck Berry. In time, blacks and whites performed on the same stage, and studio seating was desegregated.[23] Beginning in 1959 and continuing into the mid-1960s, Clark produced and hosted the Caravan of Stars, a series of concert tours built upon the success of American Bandstand, which by 1959 had a national audience of 20 million.[29] However, Clark was unable to host Elvis Presley, the Beatles or the Rolling Stones on either of his programs.[17]

The reason for Clark's impact on popular culture has been partially explained by Paul Anka, a singer who appeared on the show early in his career: "This was a time when there was no youth culture — he created it. And the impact of the show on people was enormous."[31] In 1990, a couple of years after the show had been off the air, Clark considered his personal contribution to the music he helped introduce:

My talent is bringing out the best in other talent, organizing people to showcase them and being able to survive the ordeal. I hope someday that somebody will say that in the beginning stages of the birth of the music of the fifties, though I didn't contribute in terms of creativity, I helped keep it alive.[25]

Payola hearings[edit]

In 1960, the United States Senate investigated payola, the practice of music-producing companies paying broadcasting companies to favor their product. As a result, Clark's personal investments in music publishing and recording companies were considered a conflict of interest, and he sold his shares in those companies.[32]

When asked about some of the causes for the hearings, Clark speculated about some of the contributing factors not mentioned by the press:

Politicians . . . did their damnedest to respond to the pressures they were getting from parents and publishing companies and people who were being driven out of business [by rock]. . . . It hit a responsive chord with the electorate, the older people. . . . they full-out hated the music. [But] it stayed alive. It could've been nipped in the bud, because they could've stopped it from being on television and radio.[25]

As reported by a New York Times Magazine interview with Dick Clark, Gene Shalit was Clark's press agent in the early 1960s. Shalit reportedly "stopped representing" Clark during the Congressional investigation of payola. Clark never spoke to Shalit again, and referred to him as a "jellyfish".[33]

Game show host[edit]

Beginning in late 1963, Clark branched out into hosting game shows, presiding over The Object Is.[34] The show was canceled in 1964 and replaced by Missing Links, which had moved from NBC. Clark took over as host, replacing Ed McMahon.[34]

Clark became the first host of The $10,000 Pyramid, which premiered on CBS March 26, 1973.[35] The show — a word-association game created and produced by daytime television producer Bob Stewart — moved to ABC in 1974. Over the coming years, the top prize changed several times (and with it the name of the show), and several primetime spinoffs were created.[35]

As the program moved back to CBS in September 1982, Clark continued to host the daytime version through most of its history, winning three Emmy Awards for best game show host.[36] In total, Pyramid won nine Emmy Awards for best game show during his run, a mark that is eclipsed only by the twelve won by the syndicated version of Jeopardy!.[37] Clark's final Pyramid hosting gig, The $100,000 Pyramid, ended in 1988.[38]

Clark subsequently returned to Pyramid as a guest in later incarnations. During the premiere of the John Davidson version in 1991, Clark sent a pre-recorded message wishing Davidson well in hosting the show. In 2002, Clark played as a celebrity guest for three days on the Donny Osmond version. Earlier, he was also a guest during the Bill Cullen version of The $25,000 Pyramid, which aired simultaneously with Clark's daytime version of the show.[39]

Entertainment Weekly credited Clark's "quietly commanding presence" as a major factor in the game show's success.[35]

Clark hosted the syndicated television game show The Challengers, during its only season (1990–91). The Challengers was a co-production between the production companies of Dick Clark and Ron Greenberg. During the 1990–91 season, Clark and Greenberg also co-produced a revival of Let's Make a Deal for NBC with Bob Hilton as the host. Hilton was later replaced by original host Monty Hall. Clark later hosted Scattergories on NBC in 1993; and The Family Channel's version of It Takes Two in 1997. In 1999, along with Bob Boden, he was one of the executive producers of Fox's TV game show Greed, which ran from November 5, 1999, to July 14, 2000, and was hosted by Chuck Woolery. At the same time, Clark also hosted the Stone-Stanley-created Winning Lines, which ran for six weeks on CBS from January 8 through February 12, 2000, Geraldo Rivera was actually supposed to host Winning Lines but couldn't agree on the contract, so CBS selected Clark to host.[40]

He concluded his game show hosting career with another of his productions, Challenge of the Child Geniuses, a series of two two-hour specials broadcast on Fox in May and November 2000.

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve[edit]

In 1972, Dick Clark first produced New Year's Rockin' Eve, a New Year's Eve music special for NBC which included coverage of the ball drop festivities in New York City. Clark aimed to challenge the dominance of Guy Lombardo's New Year's specials on CBS, as he believed its big band music was too dated. After two years on NBC—during which the show was hosted by Three Dog Night and George Carlin, respectively—the program moved to ABC, and Clark assumed hosting duties. Following Lombardo's death in 1977, Rockin' Eve experienced a surge in popularity and later became the most-watched annual New Year's Eve broadcast. Clark also served as a special correspondent for ABC News's ABC 2000 Today broadcast, covering the arrival of 2000.[41][42][43]

Following his stroke (which prevented him from appearing at all on the 2004–05 edition),[44] Clark returned to make brief appearances on the 2005–06 edition while ceding the majority of hosting duties to Ryan Seacrest. Reaction to Clark's appearance was mixed. While some TV critics (including Tom Shales of The Washington Post, in an interview with the CBS Radio Network) felt that he was not in good enough shape to do the broadcast, stroke survivors and many of Clark's fans praised him for being a role model for people dealing with post-stroke recovery.[42][45] Seacrest remained host and an executive producer of the special, assuming full duties after Clark's death.[46]

Radio programs[edit]

Clark's first love was radio and, in 1963, he began hosting a radio program called The Dick Clark Radio Show. It was produced by Mars Broadcasting of Stamford. Despite Clark's enormous popularity on American Bandstand, the show was only picked up by a few dozen stations and lasted less than a year.[47]

On March 25, 1972, Clark hosted American Top 40, filling in for Casey Kasem.[48] In 1981, he created The Dick Clark National Music Survey for the Mutual Broadcasting System.[36] The program counted down the top 30 contemporary hits of the week in direct competition with American Top 40. Clark left Mutual in October 1985, and Bill St. James (and later Charlie Tuna) took over the National Music Survey.[36] Clark's United Stations purchased RKO Radio Network in 1985 and, when Clark left Mutual, he began hosting USRN's "Countdown America" which continued until 1995.

In 1982, Clark launched his own radio syndication group with partners Nick Verbitsky and Ed Salamon called the United Stations Radio Network. That company later merged with the Transtar Network to become Unistar. In 1994, Unistar was sold to Westwood One Radio. The following year, Clark and Verbitsky started over with a new version of the USRN, bringing into the fold Dick Clark's Rock, Roll & Remember, written and produced by Pam Miller (who also came up with the line used in the show and later around the world: "the soundtrack of our lives"), and a new countdown show: The U.S. Music Survey, produced by Jim Zoller. Clark served as its host until his 2004 stroke.[36] United Stations Radio Networks continues in operation as of 2020.

Dick Clark's longest-running radio show began on February 14, 1982. Dick Clark's Rock, Roll & Remember was a four-hour oldies show named after Clark's 1976 autobiography. The first year, it was hosted by veteran Los Angeles disc jockey Gene Weed. Then in 1983, voiceover talent Mark Elliot co-hosted with Clark. By 1985, Clark hosted the entire show. Pam Miller wrote the program and Frank Furino served as producer. Each week, Clark profiled a different artist from the rock and roll era and counted down the top four songs that week from a certain year in the 1950s, 1960s or early 1970s. The show ended production when Clark suffered his 2004 stroke. Reruns from the 1995–2004 era continued to air in syndication until USRN withdrew the show in 2020.

Other television programs[edit]

At the peak of his American Bandstand fame, Clark also hosted a 30-minute Saturday night program called The Dick Clark Show (aka The Dick Clark Saturday Night Beech-Nut Show). It aired from February 15, 1958, until September 10, 1960, on the ABC television network. It was broadcast live from the "Little Theater" in New York City and was sponsored by Beech-Nut gum. It featured the rock and roll stars of the day lip-synching their hits, just as on American Bandstand. However, unlike the afternoon Bandstand program, which focused on the dance floor with the teenage audience demonstrating the latest dance steps, the audience of The Dick Clark Show sat in a traditional theater setting. While some of the musical numbers were presented simply, others were major production numbers. The high point of the show was Clark's unveiling, with great fanfare at the end of each program, of the top ten records of the previous week.[49] This ritual became so embedded in American culture that it was imitated in many media and contexts, which in turn were satirized nightly by David Letterman on his own Top Ten lists.

From September 27 to December 20, 1959, Clark hosted a 30-minute weekly talent/variety series entitled Dick Clark's World of Talent at 10:30 p.m. Sundays on ABC. A variation of producer Irving Mansfield's earlier CBS series, This Is Show Business (1949–1956), it featured three celebrity panelists, including comedian Jack E. Leonard, judging and offering advice to amateur and semi-professional performers. While this show was not a success during its nearly three-month duration, Clark was one of the few personalities in television history on the air nationwide seven days a week.[49]

One of Clark's guest appearances was in the final episode ("The Case of the Final Fade-Out") of the original Perry Mason TV series, playing a character named "Leif Early" in a show that satirized the show business industry. [50] He appeared as a drag-racing-strip owner in a 1973 episode of the procedural drama series Adam-12.

Clark appeared in an episode of Police Squad!, in which he asks an underworld contact about ska and obtains skin cream to keep himself looking young.

Clark attempted to branch into the realm of soul music with the series Soul Unlimited in 1973. The series, hosted by Buster Jones, was a more risqué and controversial imitator of the popular series Soul Train and alternated in the Bandstand time slot. The series lasted for only a few episodes.[51] Despite a feud between Clark and Soul Train creator and host Don Cornelius,[52] the two men later collaborated on several specials featuring black artists.

Clark hosted the short-lived Dick Clark's Live Wednesday in 1978 for NBC.[53] In 1980, Clark served as host of the short-lived series The Big Show, an unsuccessful attempt by NBC to revive the variety show format of the 1950s/60s. In 1984, Clark produced and hosted the NBC series TV's Bloopers & Practical Jokes with co-host Ed McMahon. Clark and McMahon were longtime Philadelphia acquaintances, and McMahon praised Clark for first bringing him together with future TV partner Johnny Carson when all three worked at ABC in the late 1950s. The Bloopers franchise stemmed from the Clark-hosted (and produced) NBC Bloopers specials of the early 1980s, inspired by the books, record albums and appearances of Kermit Schafer, a radio and TV producer who first popularized outtakes of broadcasts.[50] For a period of several years in the 1980s, Clark simultaneously hosted regular programs on all three major American television networks – ABC (Bandstand), CBS (Pyramid), and NBC (Bloopers).[54]

In July 1985, Clark hosted the ABC primetime portion of the historic Live Aid concert, an all star concert designed by Bob Geldof to end world hunger.[55] During the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike, Clark (as host and producer) filled in a void on CBS' fall schedule with Live! Dick Clark Presents.[56]

Clark also hosted various pageants from 1988 to 1993 on CBS. He did a brief stint as announcer on The Jon Stewart Show in 1995.[57] Two years later, he hosted the Pennsylvania Lottery 25th Anniversary Game Show special with then-Miss Pennsylvania Gigi Gordon for Jonathan Goodson Productions. He also created and hosted two Fox television specials in 2000 called Challenge of the Child Geniuses,[58] the last game show he hosted.[citation needed]

From 2001 to 2003, Clark was a co-host of The Other Half with Mario Lopez, Danny Bonaduce and Dorian Gregory, a syndicated daytime talk show intended to be the male equivalent of The View. Clark also produced the television series American Dreams about a Philadelphia family in the early 1960s whose daughter is a regular on American Bandstand. The series ran from 2002 to 2005.[50]

Other media appearances[edit]

Clark wrote, produced and starred in the 1968 film Killers Three, a Western drama that served as a promotional vehicle for Bakersfield country musicians Merle Haggard and Bonnie Owens.

In 1967, Clark made an appearance in the Batman television series. Clark also appears in interview segments of a 2002 film, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, which was based on the "unauthorized autobiography" of Chuck Barris, who had worked at ABC as a standards-and-practices executive during American Bandstand's run on that network.[59]

In the 2002 Dharma & Greg episode "Mission: Implausible", Greg is the victim of a college prank, and he devises an elaborate plan to retaliate, part of which involves his use of a disguise kit; the first disguise chosen is that of Dick Clark. During a fantasy sequence that portrays the unfolding of the plan, the real Clark plays Greg wearing his disguise.[60]

He also made brief cameos in two episodes of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. In one episode he plays himself at a Philadelphia diner, and in the other he helps Will Smith's character host bloopers from past episodes of that sitcom.[61]

With Ed McMahon, Clark was a spokesman for American Family Sweepstakes until he quit over controversy from the company regarding their sales techniques.[62] Though McMahon continued until the company went out of business, Clark's previous involvement in the Payola scandal motivated him to be sensitive about his public image.

Business ventures[edit]

In 1965, Clark branched out from hosting, producing Where the Action Is, an afternoon television program shot at different locations every week featuring house band Paul Revere and the Raiders.[7] In 1973, Clark began producing the highly-successful American Music Awards.[7] In 1987, Dick Clark Productions went public.[7] Clark remained active in television and movie production into the 1990s.[7]

Clark had a stake in a chain of music-themed restaurants licensed under the names "Dick Clark's American Bandstand Grill",[63] "Dick Clark's AB Grill", "Dick Clark's Bandstand — Food, Spirits & Fun" and "Dick Clark's AB Diner".[64] There are currently two airport locations in Newark, New Jersey and Phoenix, Arizona; one location in the Molly Pitcher travel plaza on the New Jersey Turnpike in Cranbury, New Jersey; and one location at "Dick Clark's American Bandstand Theater" in Branson, Missouri. Until recently, Salt Lake City, Utah had an airport location.[65] Other restaurants that have closed were located in King Of Prussia (Pennsylvania); Miami; Columbus; Cincinnati; Indianapolis; and Overland Park (Kansas).

"Dick Clark's American Bandstand Theater" opened in Branson in April 2006,[66] and nine months later, a new theater and restaurant entitled "Dick Clark's American Bandstand Music Complex" opened near Dolly Parton's Dollywood theme park in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.[67]

From 1979 to 1980, Clark reportedly owned the former Westchester Premier Theatre in Greenburgh, New York, renaming it the Dick Clark Westchester Theatre.[68]

Personal life[edit]

Clark was the son of Richard A. Clark, who managed WRUN radio in Utica, New York.[69]

He was married three times. His first marriage was to Barbara Mallery in 1952; the couple had one son, Richard A. Clark, and divorced in 1961. He married Loretta Martin in 1962; the couple had two children, Duane and Cindy, and divorced in 1971. His third marriage, to Kari Wigton, whom he married in 1977, lasted until his death. He also had three grandchildren.[70]

Illness and death[edit]

During an interview on Larry King Live in April 2004, Clark revealed that he had type 2 diabetes.[71][72] His death certificate noted that Clark had coronary artery disease at the time of his death.[73]

In December 2004, Clark was hospitalized in Los Angeles after suffering what was initially termed a minor stroke. Although he was expected to be treated without any serious complications, it was later announced that Clark would be unable to host his annual New Year's Rockin' Eve broadcast, with Regis Philbin filling in for him. Clark returned to the series the following year, but the dysarthria that resulted from the stroke rendered him unable to speak clearly for the remainder of his life.

On April 18, 2012, Clark died from a heart attack at a hospital in Santa Monica, California, aged 82, shortly after undergoing a transurethral resection procedure to treat an enlarged prostate.[73][48] After his estate obtained the necessary environmental permits, he was cremated on April 20, and his ashes were scattered over the Pacific Ocean.[74]

Legacy[edit]

Following Clark's death, longtime friend and House Rules Committee Chairman David Dreier eulogized Clark on the floor of the U.S. Congress.[75] President Barack Obama praised Clark's career: "With American Bandstand, he introduced decades' worth of viewers to the music of our times. He reshaped the television landscape forever as a creative and innovative producer. And, of course, for 40 years, we welcomed him into our homes to ring in the New Year."[76] Motown founder Berry Gordy and singer Diana Ross spoke of Clark's impact on the recording industry: "Dick was always there for me and Motown, even before there was a Motown. He was an entrepreneur, a visionary and a major force in changing pop culture and ultimately influencing integration," Gordy said. "He presented Motown and the Supremes on tour with the "Caravan of Stars" and on American Bandstand, where I got my start," Ross said.[77]

Credits[edit]

Filmography[edit]

- Jamboree (1957) – Himself

- Because They're Young (1960) – Neil Hendry

- The Young Doctors (1961) – Dr. Alexander

- Killers Three (1968) – Roger

- The Phynx (1970) – Himself

- Spy Kids (2001) – Financier

- Bowling For Columbine (2002) – Himself (Documentary)

Television[edit]

- ABC 2000 Today – Times Square correspondent

- Adam-12 (1972) – as drag strip owner Mr. J. Benson in the season 4 episode "Who Won?"

- American Bandstand – host

- Branded – guest-starred as J.A. Bailey in season 2 episode "The Greatest Coward on Earth"

- Burke's Law – as Peter Barrows, the son of a murdered financier in season 1 episode "Who Killed What His Name?"

- Coronet Blue – guest-starred as Victor Brunswick in the episode "The Flip Side of Timmy Devon"

- The Challengers – host

- The Chamber – producer

- Futurama – himself (as a head in a jar), season 1, episode 1, "Space Pilot 3000"

- Greed – producer

- Happening (1968–69) – producer

- It Takes Two (1997) – host

- The Krypton Factor (1981) – host

- Lassie (1966) – as J.H. Alpert in the episode "The Untamed Land"

- Missing Links (1964) – host

- Miss Teen USA (1988, 1991–1993) – host

- Miss Universe (1990–1993) – host

- Miss USA (1989–1993) – host

- Final Draw: 1994 FIFA World Cup (1993) – host

- New Year's Rockin' Eve (1972–2004) – host, (2006–2012) – co-host, producer

- Perry Mason, (1966) Season 9, episode 30, "The Case of the Final Fadeout"

- The Object Is (1963–1964) – host

- The Partridge Family, guest star, season 1, episode 13, Star Quality

- Pyramid – host (1973–1988), guest (The $25,000 Pyramid, 1970s; Pyramid, 2002)

- The Saturday Night Beech-Nut Show (1958–1960) – host

- Scattergories – host

- Stoney Burke (1963) – Sgt. Andy Kincaid in the episode "Kincaid"

- TV's Bloopers & Practical Jokes – co-host, producer

- Where the Action Is (1965–67) – host

- Police Squad! – himself, episode "Testimony of Evil (Dead Men Don't Laugh)"

- Wolf Rock TV – producer

- Winning Lines – host

- The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air – himself (two episodes)

Albums[edit]

- Dick Clark, 20 Years of Rock N' Roll (Buddah Records) (1973) (#9 Canada[78])

- Rock, Roll & Remember, Vol. 1,2,3 (CSP) (1983)

- Dick Clark Presents Radio's Uncensored Bloopers (Atlantic) (1984)

Awards and honors[edit]

Television

- Five Emmy Awards

- Four for Best Game Show Host (1979, 1983, 1985, and 1986)

- Daytime Emmy Lifetime Achievement Award (1994)

- Peabody Award (1999)

Halls of Fame

- Hollywood Walk of Fame (1976)

- National Radio Hall of Fame (1990)[79]

- Broadcasting Magazine Hall of Fame (1992)

- Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia Hall of Fame (1992)

- Television Hall of Fame (1992)

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1993)

- Disney Legends (2013)

Organizational

- Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia Person of the Year (1980)

References[edit]

- ^ "Dick Clark on". TV. July 19, 2010. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Dick Clark's death record at Family Search

- ^ a b "Dick Clark Biography". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "World's oldest teenager dies at 82". Eagle-Tribune. April 19, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Bruce Weber (April 18, 2012). "TV Emperor of Rock 'n' Roll and New Year's Eve Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ "Michigan Military Heritage Museum". www.gluseum.com. June 24, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q DK Peneny. "Dick Clark". The History of Rock 'n' Roll. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Dick Clark". AskMen.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Dick; Robinson, Richard (1976). Rock, Roll and Remember. New York City: Thomas Y. Crowell Co. ISBN 978-0-690-01184-5.

- ^ "KPRO, WLOB sales announced" (PDF). Broadcasting. December 28, 1964. p. 9. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ "Changing Hands" (PDF). Broadcasting. March 27, 1978. p. 43. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ "Changing Hands" (PDF). Broadcasting. November 13, 1967. p. 51. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ Tiegel, Eliot (July 8, 1967). "Smothers Set Youthful Pace" (PDF). Billboard. p. 32. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- ^ Dan Deluca, Sam Wood and Michael D. Schaffer (April 18, 2012). "Dick Clark, legendary host of 'American Bandstand,' dies at 82". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012 – via Kansas City Star.

- ^ "Dick Clark — Elvis 1961 Interview; American Bandstand Compare: Dick Clark; Dick Clark's Elvis Collection Sold at Auction". Elvis Presley News. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ Bertram, Colin (April 18, 2012). "The Dick Clark Effect: It's Everywhere". NBC Chicago. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c Geoff Boucher (April 19, 2012). "Dick Clark dies at 82; he introduced America to rock 'n' roll". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Sullivan, James (April 18, 2012). "The Legacy of Dick Clark". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Kay, Jonathan. "The colour of Dick Clark's cash: Jonathan Kay on American Bandstand, race, and money in 1950s Philadelphia". National Post.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (April 19, 2012). "5 Ways Dick Clark Revolutionized the TV and Music Industry". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Whitaker, Tim (March 1, 2012). "Dick Clark's American Bandstand Didn't Originally Allow Black Dancers". Philadelphia Magazine. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Eichel, Molly (March 14, 2012). "Not so nice: No matter what Dick Clark says, 'American Bandstand' blocked black teens". Philly Inquirer. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Milner, Andrew (ed.) Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Vol. I, St. James Press (2000) pp. 525–527.

- ^ American Bandstand 30 Year Special – 1982 (2/11) on YouTube

- ^ a b c d e Schipper, Henry. "Dick Clark", Rolling Stone, April 19, 1990, pp. 67–70, 126.

- ^ "The Legacy of Dick Clark, 'The Fastest Follower in the Business'", Rolling Stone, April 18, 2012.

- ^ American Bandstand 50th Anniversary clip 2002 on YouTube

- ^ Natalie Abrams (May 27, 2010). "Dick Clark to be Honored at Daytime Emmys". TV Guide. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c Oldenburg, Ann. "TV legend Dick Clark dies at age 82", USA Today, April 18, 2012.

- ^ "Dick Clark dead at 82", CBS News, April 18, 2012.

- ^ "Reactions to Death of Dick Clark, New Year's Eve Icon" The New York Times blog, April 18, 2012.

- ^ Furek, Maxim W. (1986). The Jordan Brothers — A Musical Biography of Rock's Fortunate Sons. Berwick, Pennsylvania: Kimberley Press. OCLC 15588651.

- ^ Goldman, Andrew (March 27, 2011). "Dick Clark, Still the Oldest Living Teenager". New York Times Magazine: MM14. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Object Is". TV. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c Ken Tucker (April 18, 2012). "A Dick Clark appreciation: The deceptively laid-back, conservative revolutionary". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Dick Clark's Rock Roll & Remember". Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Duane Byrge (April 18, 2012). "Dick Clark Dead of Heart Attack at 82". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Bakersfield native wins big on $100,000 Pyramid". turnto23.com. Scripps Media, Inc. July 12, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Clark returns to 'Pyramid' — but not as show's host". Deseret News. November 13, 2002. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ Adalian, Josef (February 15, 2000). "CBS will sweep away quizzer 'Winning Lines'". Variety. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Moore, Frazier (December 26, 2001). "Next week to be 25th New Year's Eve without Guy Lombardo". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Memmott, Carol (December 27, 2011). "Dick Clark: Rockin' it on New Year's since 1972". USA Today. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ Terry, Carol Burton. "New Guy Lombardo? Dick Clark sees New Year's tradition". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (December 14, 2004). "Dick Clark Hands Off The Big Ball Drop". The Washington Post. p. C1. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ "Clark Outing Cheers Stroke Survivors". CNN. Associated Press. January 4, 2006. Archived from the original on January 11, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ Oldenburg, Ann (October 23, 2013). "Ryan Seacrest extends 'New Year's Rockin' Eve' deal". USA Today. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ "Beyond 'American Bandstand': Dick Clark's career highlights, from Philly to Hollywood". The Washington Post. Associated Press. April 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Alan Duke; Chelsea J. Carter (April 19, 2012). "Only God is responsible for making more stars than Dick Clark". CNN. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle (2003). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable Shows, 1946 – present (8th, revised and updated ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-45542-0.

- ^ a b c Lynn Elber (April 18, 2012). "Dick Clark, TV and New Year's Eve icon, dies at 82". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Top 10 Things You Didn't Know About "Soul Train"". NewsOne. February 2, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Medina, Jennifer (March 9, 2012). "When the Music Stopped for Don Cornelius". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Dick Clark's Live Wednesday". TV.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Dick Clark is Thriving on Three Major Networks – NY Times.com

- ^ "Dick Clark Dies of "Massive Heart Attack"; Secret Service Resignations Amidst Scandal". CNN. April 18, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "THE TV COLUMN". The Washington Post. September 16, 1988. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Pop Will Eat Itself on The Jon Stewart Show on YouTube

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa. "Smart Kids Finish First". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Dick Clark: A Big-Screen Tribute". Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ "Dharma & Greg Mission: Implausible TV.com". Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air: The Philadelphia Story:Overview". Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ "Dick Clark will keep pitching millions". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Howard, Bob (May 25, 1999). "Dick Clark Tries Theme Variation for Restaurants". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ "- Dick Clark's American Bandstand Diner debuts..." Chicago Tribune. December 2, 1999. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ [1] Archived December 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tornado-damaged theater to reopen April 14". Springfield News Leader. April 5, 2012. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ Jeanna Contino (April 18, 2012). "The Eventful Life of Dick Clark". BUnow. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ Kanwar, Tanuja (April 18, 2012). "Westchester Native Dick Clark Dead at 82". The Rivertowns Daily Voice. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "TV Star Clark Buys Inland Empire Station KPRO," San Bernardino Sun-Telegram, June 20, 1965, page D-4

- ^ "Dick Clark dead at 82: The TV legend's life in photos (slides 6, 7, 11 & 12)". New York Daily News. April 18, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Dick Clark dies at 82". Patriot Ledger. Quincy, Massachusetts. April 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "CNN Larry King Live — Interview With Dick Clark". CNN. April 16, 2004. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Dick Clark death certificate, autopsyfiles.org; accessed November 16, 2016.

- ^ Rene Lynch (April 19, 2012). "Dick Clark dies at 82: He was a symbol of hope to stroke victims". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (April 18, 2012). "GOP lawmaker: Dick Clark should be remembered as model of free enterprise". The Hill. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Celebrities react to the death of Dick Clark". Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Celebrities react to the death of Dick Clark". NPR. Associated Press. April 18, 2012. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "RPM Magazine - October 13, 1973 - Page 12" (PDF).

- ^ "Dick Clark". National Radio Hall Of Fame. 2017. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

External links[edit]

- Dick Clark's personal/radio web site

- Dick Clark Productions

- Dick Clark Papers at Syracuse University

- Dick Clark at the National Radio Hall of Fame

- Dick Clark at IMDb

- Dick Clark at the TCM Movie Database

- "Dick Clark". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

- Dick Clark discography at Discogs

- Dick Clark in the Hollywood Walk of Fame Directory

- Dick Clark's Rock, Roll and Remember newspaper comic strip series

- Dick Clark interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (recorded March 11, 1968)

- Dick Clark collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia web page

- Dick Clark at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- FBI file on Dick Clark

- Reuters review of 2008 documentary The Wages of Spin [2]

- Dick Clark

- 1929 births

- 2012 deaths

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- Actors from Mount Vernon, New York

- American chief executives in the media industry

- American company founders

- American game show hosts

- American radio DJs

- American radio personalities

- American restaurateurs

- Businesspeople from New York (state)

- Culture of Philadelphia

- Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Game Show Host winners

- Deaths from coronary artery disease

- Disney Legends

- Mount Vernon High School (New York) alumni

- Peabody Award winners

- People from Bronxville, New York

- People from Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania

- People with Parkinson's disease

- S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications alumni

- Television producers from New York (state)

- Television show creators