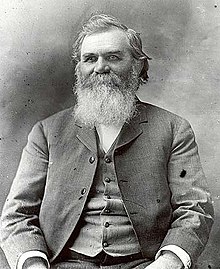

Daniel David Palmer

Daniel David Palmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 7, 1845 |

| Died | October 20, 1913 (aged 68) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | Canadian-American |

| Occupation | Chiropractor |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | B. J. Palmer |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Daniel David Palmer (March 7, 1845 – October 20, 1913) was the founder of chiropractic.[4] Palmer was born in Pickering Township, Canada West,[2][3] but emigrated to the United States in 1865.[5] He was also an avid proponent of pseudoscientific alternative medicine such as magnetic healing. Palmer opposed anything he thought to be associated with mainstream medicine such as vaccination.[6]

Palmer believed that the human body had an ample supply of natural healing power transmitted through the nervous system. He suggested that if any one organ was affected by an illness, it merely must not be receiving its normal "nerve supply" which he dubbed a "spinal misalignment", or subluxation. He saw chiropractic as a form of realigning to reestablish the supply.

Early life[edit]

Palmer was born in the hamlet of Brown's Corners (later Audley) of Pickering Township, in what is now Ajax, Ontario.[1][7] His parents were Thomas Palmer and Katherine McVay, and his great-great-grandparents were from the United States.[8] He received formal education until the age of 11 years,[7][9] at the Audley School,[10] and was subsequently raised in Port Perry.[1]

At age twenty he moved to the United States with his family. Palmer held various jobs such as a beekeeper, school teacher, and grocery store owner, and had an interest in the various health philosophies of his day, including magnetic healing and spiritualism. In 1870 Palmer was probably a student of metaphysics.[11] Palmer practiced magnetic healing beginning in the mid-1880s in Burlington and Davenport, Iowa.

Founding of chiropractic[edit]

In 1895, Palmer was practicing magnetic healing from an office in Davenport when he encountered the building's janitor, Harvey Lillard. Lillard's hearing was severely impaired, and Palmer theorized that a palpable lump in his back that Palmer had noticed was related to Lillard's hearing deficits.[12] Palmer then treated Lillard's back and claimed to have successfully restored his hearing,[13] a claim which was influential in chiropractic history.

This account of how the first adjustment came to be would later be countered by Lillard's daughter who recounts a different interaction between the two men, as told to her by her father. She claims that Palmer overheard Lillard telling a joke just outside his office, and joined the group to catch the end of it. Upon hearing the punchline, Palmer heartily slapped Lillard on the back. A few days later Lillard remarked that his hearing had improved since the incident, inspiring Palmer to pursue vertebral treatment as a means to cure disease.[14]

In 1896, D. D. Palmer's first descriptions and underlying philosophy of chiropractic was strikingly similar to Andrew Still's principles of osteopathy established a decade earlier.[15] Both described the body as a "machine" whose parts could be manipulated to produce a drugless cure. Both professed the use of spinal manipulation on joint dysfunction to improve health; chiropractors dubbed this manipulable lesion "subluxation" which interfered with the nervous system whereas osteopaths dubbed the spinal lesion "somatic dysfunction" which affected the circulatory system. Palmer drew further distinctions by noting that he was the first to use short-lever manipulative techniques using the spinous process and transverse processes as mechanical levers to spinal dysfunction/subluxation.[12] Soon after, osteopaths began an American wide campaign proclaimed that chiropractic was a bastardized form of osteopathy and sought licensure to differentiate the two groups.[15] Although Palmer initially denied being trained by osteopathic medicine founder A. T. Still, in 1899 he wrote:

Some years ago I took an expensive course in Electropathy, Cranial Diagnosis, Hydrotherapy, Facial Diagnosis. Later I took Osteopathy [which] gave me such a measure of confidence as to almost feel it unnecessary to seek other sciences for the mastery of curable disease. Having been assured that the underlying philosophy of chiropractic is the same as that of osteopathy...Chiropractic is osteopathy gone to seed.[11]

His theories revolved around the concept that altered nerve flow was the cause of all disease, and that misaligned spinal vertebrae had an effect on the nerve flow. He postulated that restoring these vertebrae to their proper alignment would restore health.

A subluxated vertebra ... is the cause of 95 percent of all diseases ... The other five percent is caused by displaced joints other than those of the vertebral column.[13]

Spread of chiropractic[edit]

Palmer began teaching others his new treatment methods. In 1897, he founded the Palmer School and Cure in Davenport, later renamed Palmer College of Chiropractic. Among Palmer's early students was his son B.J. Palmer.[16]

In 1906, Palmer was prosecuted under the new medical arts law in Iowa for practicing medicine without a license, and chose to go to jail instead of paying the fine. As a result, he spent 17 days in jail, but then elected to pay the fine. Shortly thereafter, he sold the school of chiropractic to B.J. Palmer. After the sale of the school was finalized, D. D. Palmer went to the western United States, where he helped to found chiropractic schools in Oklahoma, California, and Oregon.

Palmer's beliefs[edit]

Spiritualism[edit]

As an active spiritist, D. D. Palmer said he "received chiropractic from the other world"[17] from a deceased medical physician named Dr. Jim Atkinson.[18]

According to his son, B. J. Palmer, "Father often attended the annual Mississippi Valley Spiritualists Camp Meeting where he first claimed to receive messages from Dr. Jim Atkinson on the principles of chiropractic."[19][20]

The knowledge and philosophy given me by Dr. Jim Atkinson, an intelligent spiritual being, together with explanations of phenomena, principles resolved from causes, effects, powers, laws and utility, appealed to my reason. The method by which I obtained an explanation of certain physical phenomena, from an intelligence in the spiritual world, is known in biblical language as inspiration. In a great measure The Chiropractor's Adjuster was written under such spiritual promptings. (p. 5)[20]

He regarded chiropractic as partly religious in nature. At various times he wrote:

... we must have a religious head, one who is the founder, as did Christ, Muhammad, Jo. Smith, Mrs. Eddy, Martin Luther and other who have founded religions. I am the fountain head. I am the founder of chiropractic in its science, in its art, in its philosophy and in its religious phase.[17]

... nor interfere with the religious duty of chiropractors, a privilege already conferred upon them. It now becomes us as chiropractors to assert our religious rights. (p. 1)[20]

The practice of chiropractic involves a moral obligation and a religious duty. (p. 2)[20]

By correcting these displacements of osseous tissue, the tension frame of the nervous system, I claim that I am rendering obedience, adoration and honor to the All-Wise Spiritual Intelligence, as well as a service to the segmented, individual portions thereof – a duty I owe to both God and mankind. In accordance with this aim and end, the Constitution of the United States and the statutes personal of California confer upon me and all persons of chiropractic faith the inalienable right to practice our religion without restraint or interference.[20](p. 12)

He distanced himself from actually renaming the profession to the "religion of chiropractic" and discussed the differences between a formal, objective religion and a personal, subjective ethical religious belief.[20](p. 6)

Magnetic healer[edit]

Like other drugless healers of the era, Palmer practised as a magnetic healer prior to founding chiropractic. Palmer sought to combine magnetic, scientific and vitalistic viewpoints as a drugless healer.

In 1886 I began as a business. Although I practiced under the name of magnetic, I did not slap or rub, as others. I questioned many M.D.s as to the cause of disease. I desired to know why such a person had asthma, rheumatism, or other afflictions. I wished to know what differences there were in two persons that caused one to have certain symptoms called disease which his neighbor living under the same conditions did not have...In my practice of the first 10 years which I named magnetic, I treated nerves, followed and relieved them of inflammation. I made many good cures, as many are doing today under a similar method.[20]

He met opposition throughout his life, including locally, and was accused of being a crank and a quack. An 1894 edition of the local paper, the Davenport Leader, wrote:

A crank on magnetism has a crazy notion that he can cure the sick and crippled with his magnetic hands. His victims are the weak-minded, ignorant and superstitious, those foolish people who have been sick for years and have become tired of the regular physician and want health by the short-cut method ... he has certainly profited by the ignorance of his victims ... His increase in business shows what can be done in Davenport, even by a quack.[21]

Anti-vaccination[edit]

Like his son, Palmer was anti-vaccines:

It is the very height of absurdity to strive to 'protect' any person from smallpox or any other malady by inoculating them with a filthy animal poison.

— D. D. Palmer[6]

The Palmers espoused anti-vaccination opinions in the early part of the 20th century, rejecting the germ theory of disease in favor of a worldview that a subluxation-free spine, achieved by spinal adjustments, would result in an unfettered innate intelligence;....[22]

Quotes[edit]

- Disease: "The kind of dis-ease depends upon what nerves are too tense or too slack."

- Chiropractic for intellectual abnormalities: "Chiropractors correct abnormalities of the intellect as well as those of the body."'

- Life and religion: "I have answered the time-worn question—what is life?": "The dualistic system—spirit and body—united by intellectual life—the soul—is the basis of this science of biology"

- "There can be no healing without Teaching ..."

- "There is a vast difference between treating effects and adjusting the causes."[20]

Personal life[edit]

Palmer was married six times.

- Abba Lord, m. 1871[23]

- Louvenia Landers, m. 1874 – d. 1884[23]

- Lavinia McGee, m. 1876 – d. 1885[23]

- Martha A. Henning, m. 1885[23]

- Villa Amanda Thomas, m. 1888 – d. 1905[23]

- Molly Hudler ("Mary"), m. 1906[23]

Death[edit]

The relationship with his son, B. J. Palmer, was tenuous and often bitter, especially after the sale of his school. Their subsequent disagreements regarding the direction of the emerging field of chiropractic were evident in D. D. Palmer's writings. B. J. Palmer resented his father for the way he treated his family, stating that his father beat three of his children with straps and was so much involved in chiropractic that "he hardly knew he had any children".[24] Even the circumstances surrounding his death were postulated to be attributable to B. J.

Court records reflect that during a parade in Davenport in August 1913, D. D. was marching on foot when he was struck from behind by a car driven by B. J. He died in Los Angeles, California, on October 20, 1913. The official cause of death was typhoid fever, though some believe it was the consequence of his injuries.[24] The courts exonerated B. J. of any responsibility for his father's death.

Chiropractic historian Joseph C. Keating, Jr. has described the attempted patricide of D. D. Palmer as a "myth" and "absurd on its face" and cites an eyewitness who recalled that D. D. was not struck by B. J.'s car but rather had stumbled. He also says that "Joy Loban, DC, executor of D. D.'s estate, voluntarily withdrew a civil suit claiming damages against B. J. Palmer, and that several grand juries repeatedly refused to bring criminal charges against the son."[25][26]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c John Robert Colombo (2011). Fascinating Canada. Dundurn Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9781554889242.

- ^ a b Keating, Joseph Jr. (June 4, 2005). "The Palmers and the Port Perry Myths". Dynamic Chiropractic. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

I was born on March 7, 1845, a few miles east of Toronto, Canada.

- ^ a b Palmer College of Chiropractic Health Sciences Library (March 1, 2022). "Daniel David Palmer". Palmer College of Chiropractic. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Enright, Matt (September 18, 2019). "Palmer College of Chiropractic honors its founder D. D. Palmer, with a new statue". The Quad-City Times.

- ^ Kirkey, Sharon; Hall, Brice (July 2, 2019). "The first chiropractor was a Canadian who claimed he received a message from a ghost". The Star Phoenix.

- ^ a b Busse JW, Morgan L, Campbell JB (2005). "Chiropractic antivaccination arguments". J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 28 (5): 367–73. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.04.011. PMID 15965414.

- ^ a b Paul Benedetti; Wayne MacPhail (2003). Spin Doctors: The Chiropractic Industry Under Examination. Dundurn Press. p. 25. ISBN 9781770701250.

- ^ "Ancestry of Daniel David Palmer". Wargs.com. October 20, 1913. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ Robert Hartmann McNamara (2018). Chiropractic Medicine: An Ethnographic Study. Lexington Books. p. 34. ISBN 9781498591416.

- ^ Donald McDowall; Marilyn Chaseling; Elizabeth Emmanuel; Sandra Grace (2019). "Daniel David Palmer, the Father of Chiropractic: His Heritage Revisited". Chiropractic History. 39 (1): 32.

D. D. received his formal education at the Audley School in the Pickering Township close to his home.

- ^ a b Leach, Robert (2004). The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. p. 15. ISBN 978-0683307474.

- ^ a b "D.D. Palmer's Lifeline" (PDF).

- ^ a b Palmer D. D., The Science, Art and Philosophy of Chiropractic. Portland, Oregon: Portland Printing House Company, 1910.

- ^ Jarvis, William T. "NCAHF Fact Sheet on Chiropractic (2001)". www.ncahf.org. NCAHF. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Ernst, E (May 2008). "Chiropractic: a critical evaluation". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 35 (5): 544–62. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.004. ISSN 0885-3924. PMID 18280103.

- ^ "The Palmer Family". www.palmer.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ a b D.D. Palmer's Religion of Chiropractic – Letter from D. D. Palmer to P. W. Johnson, D.C., May 4, 1911. In the letter, he often refers to himself with royal third person terminology and also as "Old Dad".

- ^ Keating J. Faulty Logic & Non-skeptical Arguments in Chiropractic Archived November 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ L. Ted Frigard, DC, PhC, Still vs. Palmer: A Remembrance of the Famous Debate, Dynamic Chiropractic – January 27, 2003, Vol. 21, Issue 03

- ^ a b c d e f g h Palmer, D. D. (June 1994). The Chiropractor. Health Research Books. p. 5. ISBN 9780787306526. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ Colquhoun, D (July 2008). "Doctor Who? Inappropriate use of titles by some alternative "medicine" practitioners". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 121 (1278): 6–10. ISSN 0028-8446. PMID 18670469. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009.

- ^ Gleberzon, Brian (September 2013). "On Vaccination & Chiropractic: when ideology, history, perception, politics and jurisprudence collide". Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 57 (3): 205–13. PMC 3743646. PMID 23997246.

- ^ a b c d e f Keating, Jr, Joseph (April 13, 1998). "D.D. Palmer's Lifeline" (PDF). chiro.org. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Singh S, Ernst E (2008). "The truth about chiropractic therapy". Trick or Treatment: The Undeniable Facts about Alternative Medicine. W.W. Norton. pp. 145–90. ISBN 978-0-393-06661-6.

- ^ Siordia L, Keating JC (1999). "Laid to uneasy rest: D.D. Palmer, 1913". Chiropr Hist. 19 (1): 23–31. PMID 11624037.

- ^ Keating, Joseph (April 23, 1993). "Dispelling Some Myths About Old Dad Chiro". Dynamic Chiropractic. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

External links[edit]

- Canadian anti-vaccination activists

- 1845 births

- 1913 deaths

- American anti-vaccination activists

- American chiropractors

- American spiritualists

- Canadian chiropractors

- Canadian spiritualists

- Germ theory denialists

- People from Davenport, Iowa

- People from Scugog

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Emigrants from pre-Confederation Ontario to the United States

- Pre-Confederation Ontario people