Citation

| Part of a series on |

| Research |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

A citation is a reference to a source. More precisely, a citation is an abbreviated alphanumeric expression embedded in the body of an intellectual work that denotes an entry in the bibliographic references section of the work for the purpose of acknowledging the relevance of the works of others to the topic of discussion at the spot where the citation appears.

Generally, the combination of both the in-body citation and the bibliographic entry constitutes what is commonly thought of as a citation (whereas bibliographic entries by themselves are not).

Citations have several important purposes. While their uses for upholding intellectual honesty and bolstering claims are typically foregrounded in teaching materials and style guides (e.g.,[2][3]), correct attribution of insights to previous sources is just one of these purposes.[4] Linguistic analysis of citation-practices has indicated that they also serve critical roles in orchestrating the state of knowledge on a particular topic, identifying gaps in the existing knowledge that should be filled or describing areas where inquiries should be continued or replicated.[5] Citation has also been identified as a critical means by which researchers establish stance: aligning themselves with or against subgroups of fellow researchers working on similar projects and staking out opportunities for creating new knowledge.[6]

Conventions of citation (e.g., placement of dates within parentheses, superscripted endnotes vs. footnotes, colons or commas for page numbers, etc.) vary by the citation-system used (e.g., Oxford,[7] Harvard, MLA, NLM, American Sociological Association (ASA), American Psychological Association (APA), etc.). Each system is associated with different academic disciplines, and academic journals associated with these disciplines maintain the relevant citational style by recommending and adhering to the relevant style guides.

Concept[edit]

A bibliographic citation is a reference to a book, article, web page, or other published item. Citations should supply sufficient detail to identify the item uniquely.[8] Different citation systems and styles are used in scientific citation, legal citation, prior art, the arts, and the humanities. Regarding the use of citations in the scientific literature, some scholars also put forward "the right to refuse unwanted citations" in certain situations deemed inappropriate.[9]

Content[edit]

Citation content can vary depending on the type of source and may include:

- Book: authors, book title, place of publication, publisher, date of publication, and page numbers if appropriate.[10]

- Journal: authors, article title, journal title, date of publication, and page numbers.

- Newspaper: authors, article title, name of newspaper, section title and page numbers if desired, date of publication.

- Web site: authors, article, and publication title where appropriate, as well as a URL, and a date when the site was accessed.

- Play: inline citations offer part, scene, and line numbers, the latter separated by periods: 4.452 refers to scene 4, line 452. For example, "In Eugene Onegin, Onegin rejects Tanya when she is free to be his, and only decides he wants her when she is already married" (Pushkin 4.452–53).[11]

- Poem: spaced slashes are normally used to indicate separate lines of a poem, and parenthetical citations usually include the line numbers. For example: "For I must love because I live / And life in me is what you give." (Brennan, lines 15–16).[11]

- Interview: name of interviewer, interview descriptor (ex. personal interview), and date of interview.

- Data: authors, dataset title, date of publication, and publisher.

Unique identifiers[edit]

Along with information such as authors, date of publication, title and page numbers, citations may also include unique identifiers depending on the type of work being referred to.

- Citations of books may include an International Standard Book Number (ISBN).

- Specific volumes, articles, or other identifiable parts of a periodical, may have an associated Serial Item and Contribution Identifier (SICI) or an International Standard Serial Number (ISSN).

- Electronic documents may have a digital object identifier (DOI).

- Biomedical research articles may have a PubMed Identifier (PMID).

Systems[edit]

Broadly speaking, there are two types of citation systems, the Vancouver system and parenthetical referencing.[12] However, the Council of Science Editors (CSE) adds a third, the citation-name system.[13]

Vancouver system[edit]

The Vancouver system uses sequential numbers in the text, either bracketed or superscript or both.[14] The numbers refer to either footnotes (notes at the end of the page) or endnotes (notes on a page at the end of the paper) that provide source detail. The notes system may or may not require a full bibliography, depending on whether the writer has used a full-note form or a shortened-note form. The organizational logic of the bibliography is that sources are listed in their order of appearance in-text, rather than alphabetically by author last name.

For example, an excerpt from the text of a paper using a notes system without a full bibliography could look like:

- "The five stages of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance."1

The note, located either at the foot of the page (footnote) or at the end of the paper (endnote) would look like this:

- 1. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Macmillan, 1969) 45–60.

In a paper with a full bibliography, the shortened note might look like:

- 1. Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying 45–60.

The bibliography entry, which is required with a shortened note, would look like this:

- Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

In the humanities, many authors also use footnotes or endnotes to supply anecdotal information. In this way, what looks like a citation is actually supplementary material, or suggestions for further reading.[15]

Parenthetical referencing[edit]

Parenthetical referencing, also known as Harvard referencing, has full or partial, in-text, citations enclosed in circular brackets and embedded in the paragraph.[16]

An example of a parenthetical reference:

- "The five stages of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance" (Kübler-Ross, 1969, pp. 45–60).

Depending on the choice of style, fully cited parenthetical references may require no end section. Other styles include a list of the citations, with complete bibliographical references, in an end section, sorted alphabetically by author. This section is often called "References", "Bibliography", "Works cited" or "Works consulted".

In-text references for online publications may differ from conventional parenthetical referencing. A full reference can be hidden, only displayed when wanted by the reader, in the form of a tooltip.[17] This style makes citing easier and improves the reader's experience.

Styles[edit]

Citation styles can be broadly divided into styles common to the humanities and the sciences, though there is considerable overlap. Some style guides, such as the Chicago Manual of Style, are quite flexible and cover both parenthetical and note citation systems. Others, such as MLA and APA styles, specify formats within the context of a single citation system. These may be referred to as citation formats as well as citation styles.[18][19][20] The various guides thus specify order of appearance, for example, of publication date, title, and page numbers following the author name, in addition to conventions of punctuation, use of italics, emphasis, parenthesis, quotation marks, etc., particular to their style.

A number of organizations have created styles to fit their needs; consequently, a number of different guides exist. Individual publishers often have their own in-house variations as well, and some works are so long-established as to have their own citation methods too: Stephanus pagination for Plato; Bekker numbers for Aristotle; citing the Bible by book, chapter and verse; or Shakespeare notation by play.

The Citation Style Language (CSL) is an open XML-based language to describe the formatting of citations and bibliographies.

Humanities[edit]

- The Chicago style (CMOS) was developed and its guide is The Chicago Manual of Style. It is most widely used in history and economics as well as some social sciences. The closely related Turabian style—which derives from it—is for student references, and is distinguished from the CMOS by omission of quotation marks in reference lists, and mandatory access date citation.

- The Columbia style was created by Janice R. Walker and Todd Taylor to give detailed guidelines for citing internet sources. Columbia style offers models for both the humanities and the sciences.

- Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace by Elizabeth Shown Mills covers primary sources not included in CMOS, such as censuses, court, land, government, business, and church records. Includes sources in electronic format. Used by genealogists and historians.[21]

- Harvard referencing (or author-date system) is a specific kind of parenthetical referencing. Parenthetical referencing is recommended by both the British Standards Institution and the Modern Language Association. Harvard referencing involves a short author-date reference, e.g., "(Smith, 2000)", being inserted after the cited text within parentheses and the full reference to the source being listed at the end of the article.

- MLA style was developed by the Modern Language Association and is most often used in the arts and the humanities, particularly in English studies, other literary studies, including comparative literature and literary criticism in languages other than English ("foreign languages"), and some interdisciplinary studies, such as cultural studies, drama and theatre, film, and other media, including television. This style of citations and bibliographical format uses parenthetical referencing with author-page (Smith 395) or author-[short] title-page (Smith, Contingencies 42) in the case of more than one work by the same author within parentheses in the text, keyed to an alphabetical list of sources on a "works cited" page at the end of the paper, as well as notes (footnotes or endnotes).[a]

- The MHRA Style Guide is published by the Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA) and most widely used in the arts and humanities in the United Kingdom, where the MHRA is based. It is available for sale both in the UK and in the United States. It is similar to MLA style, but has some differences. For example, MHRA style uses footnotes that reference a citation fully while also providing a bibliography. Some readers find it advantageous that the footnotes provide full citations, instead of shortened references, so that they do not need to consult the bibliography while reading for the rest of the publication details.[22]

In some areas of the humanities, footnotes are used exclusively for references, and their use for conventional footnotes (explanations or examples) is avoided. In these areas, the term footnote is actually used as a synonym for reference, and care must be taken by editors and typesetters to ensure that they understand how the term is being used by their authors.

Law[edit]

- The Bluebook is a citation system traditionally used in American academic legal writing, and the Bluebook (or similar systems derived from it) are used by many courts.[23] At present, academic legal articles are always footnoted, but motions submitted to courts and court opinions traditionally use inline citations, which are either separate sentences or separate clauses. Inline citations allow readers to quickly determine the strength of a source based on, for example, the court a case was decided in and the year it was decided.

- The legal citation style used almost universally in Canada is based on the Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (AKA McGill Guide), published by McGill Law Journal.[24]

- British legal citation almost universally follows the Oxford Standard for Citation of Legal Authorities (OSCOLA).

Sciences, mathematics, engineering, physiology, and medicine[edit]

- The American Chemical Society style, or ACS style, is often used in chemistry and some of the physical sciences. In ACS style references are numbered in the text and in the reference list, and numbers are repeated throughout the text as needed.

- In the style of the American Institute of Physics (AIP style), references are also numbered in the text and in the reference list, with numbers repeated throughout the text as needed.

- Styles developed for the American Mathematical Society (AMS), or AMS styles, such as AMS-LaTeX, are typically implemented using the BibTeX tool in the LaTeX typesetting environment. Brackets with the author's initials and year are inserted in the text and at the beginning of the reference. Typical citations are listed in line with alphabetic-label format, e.g. [AB90]. This type of style is also called an "authorship trigraph".

- The Vancouver system, recommended by the Council of Science Editors (CSE), is used in medical and scientific papers and research.

- In one major variant, that used by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), citation numbers are included in the text in square brackets rather than as superscripts. All bibliographical information is exclusively included in the list of references at the end of the document, next to the respective citation number.

- The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) is reportedly the original kernel of this biomedical style, which evolved from the Vancouver 1978 editors' meeting.[25] The MEDLINE/PubMed database uses this citation style and the National Library of Medicine provides "ICMJE Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals – Sample References".[26]

- The American Medical Association has its own variant of Vancouver style with only minor differences. See AMA Manual of Style.

- The style of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), or IEEE style, encloses citation numbers within square brackets and numbers them consecutively, with numbers repeated throughout the text as needed.[27]

- In areas of biology that falls within the ICNafp (which itself uses this citation style throughout), a variant form of author-title citation is the primary method used when making nomenclatural citations and sometimes general citations (for example in code-related proposals published in Taxon), with the works in question not cited in the bibliography unless also cited in the text. Titles use standardized abbreviations following Botanico-Periodicum-Huntianum for periodicals and Taxonomic Literature 2 (later IPNI) for books.

- Pechenik citation style is a style described in A Short Guide to Writing about Biology, 6th ed. (2007), by Jan A. Pechenik.[28]

- In 1955, Eugene Garfield proposed a bibliographic system for scientific literature, to consolidate the integrity of scientific publications.[29]

Social sciences[edit]

- The style of the American Psychological Association, or APA style, published in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, is most often used in social sciences. APA citation style is similar to Harvard referencing, listing the author's name and year of publication, although these can take two forms: name citations in which the surnames of the authors appear in the text and the year of publication then appears in parentheses, and author-date citations, in which the surnames of the authors and the year of publication all appear in parentheses. In both cases, in-text citations point to an alphabetical list of sources at the end of the paper in a "references" section.

- The American Political Science Association publishes both a style manual and a style guide for publications in this field.[30] The style is close to the CMOS.

- The American Anthropological Association utilizes a modified form of the Chicago style laid out in their publishing style guide.[31]

- The ASA style of the American Sociological Association is one of the main styles used in sociological publications.

Issues[edit]

In their research on footnotes in scholarly journals in the field of communication, Michael Bugeja and Daniela V. Dimitrova have found that citations to online sources have a rate of decay (as cited pages are taken down), which they call a "half-life", that renders footnotes in those journals less useful for scholarship over time.[32]

Other experts have found that published replications do not have as many citations as original publications.[33]

Another important issue is citation errors, which often occur due to carelessness on either the researcher or journal editor's part in the publication procedure.[34] For example, a study that analyzed 1,200 randomly selected citations from three major business ethics journals concluded that an average article contains at least three plagiarized citations when authors copy and paste a citation entry from another publication without consulting the original source.[35] Experts have found that simple precautions, such as consulting the author of a cited source about proper citations, reduce the likelihood of citation errors and thus increase the quality of research.[36] Another study noted that approximately 25% citations do not support the claims made, a finding that affects many disciplines, including history.[37]

Research suggests the impact of an article can be, partly, explained by superficial factors and not only by the scientific merits of an article.[38] Field-dependent factors are usually listed as an issue to be tackled not only when comparisons across disciplines are made, but also when different fields of research of one discipline are being compared.[39] For example, in medicine, among other factors, the number of authors, the number of references, the article length, and the presence of a colon in the title influence the impact; while in sociology the number of references, the article length, and title length are among the factors.[40]

Studies of methodological quality and reliability have found that "reliability of published research works in several fields may be decreasing with increasing journal rank".[41] Nature Index recognizes that citations remain a controversial and yet important metric for academics.[42] They report five ways to increase citation counts: (1) watch the title length and punctuation;[43] (2) release the results early as preprints;[44] (3) avoid referring to a country in the title, abstract, or keywords;[45] (4) link the article to supporting data in a repository;[46] and (5) avoid hyphens in the titles of research articles.[47]

Citation patterns are also known to be affected by unethical behavior of both the authors and journal staff. Such behavior is called impact factor boosting and was reported to involve even the top-tier journals. Specifically the high-ranking journals of medical science, including The Lancet, JAMA and The New England Journal of Medicine, are thought to be associated with such behavior, with up to 30% of citations to these journals being generated by commissioned opinion articles.[48] On the other hand, the phenomenon of citation cartels is rising. Citation cartels are defined as groups of authors that cite each other disproportionately more than they do other groups of authors who work on the same subject.[49]

Research and development[edit]

There is research about citations and development of related tools and systems, mainly relating to scientific citations. Citation analysis is a method widely used in metascience.

Citation analysis[edit]

Citation analysis is the examination of the frequency, patterns, and graphs of citations in documents. It uses the directed graph of citations — links from one document to another document — to reveal properties of the documents. A typical aim would be to identify the most important documents in a collection. A classic example is that of the citations between academic articles and books.[50][51] For another example, judges of law support their judgements by referring back to judgements made in earlier cases (see citation analysis in a legal context). An additional example is provided by patents which contain prior art, citation of earlier patents relevant to the current claim. The digitization of patent data and increasing computing power have led to a community of practice that uses these citation data to measure innovation attributes, trace knowledge flows, and map innovation networks.[52]

Documents can be associated with many other features in addition to citations, such as authors, publishers, journals as well as their actual texts. The general analysis of collections of documents is known as bibliometrics and citation analysis is a key part of that field. For example, bibliographic coupling and co-citation are association measures based on citation analysis (shared citations or shared references). The citations in a collection of documents can also be represented in forms such as a citation graph, as pointed out by Derek J. de Solla Price in his 1965 article "Networks of Scientific Papers".[53] This means that citation analysis draws on aspects of social network analysis and network science.Citation frequency[edit]

Modern scientists are sometimes judged by the number of times their work is cited by others—this is actually a key indicator of the relative importance of a work in science. Accordingly, individual scientists are motivated to have their own work cited early and often and as widely as possible, but all other scientists are motivated to eliminate unnecessary citations so as not to devalue this means of judgment[54].[citation needed] A formal citation index tracks which referred and reviewed papers have referred which other such papers. Baruch Lev and other advocates of accounting reform consider the number of times a patent is cited to be a significant metric of its quality, and thus of innovation.[citation needed] Reviews often replace citations to primary studies.[55]

Citation-frequency is one indicator used in scientometrics.Progress and citation consolidation[edit]

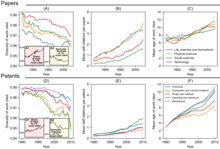

(more graphs from it)

Two metascientists reported that in a growing scientific field, citations disproportionately cite already well-cited papers, possibly slowing and inhibiting canonical progress to some degree in some cases. They find that "structures fostering disruptive scholarship and focusing attention on novel ideas" could be important.[57][58][59]

Other metascientists introduced the 'CD index' intended to characterize "how papers and patents change networks of citations in science and technology" and reported that it has declined, which they interpreted as "slowing rates of disruption". They proposed linking this to changes to three "use of previous knowledge"-indicators which they interpreted as "contemporary discovery and invention" being informed by "a narrower scope of existing knowledge". The overall number of papers has risen while the total of "highly disruptive" papers has not. The 1998 discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe has a CD index of 0. Their results also suggest scientists and inventors "may be struggling to keep up with the pace of knowledge expansion".[60][58][56]IT systems[edit]

Research discovery[edit]

Recommendation systems sometimes also use citations to find similar studies to the one the user is currently reading or that the user may be interested in and may find useful.[62] Better availability of integrable open citation information could be useful in addressing the "overwhelming amount of scientific literature".[61]

Q&A agents[edit]

Knowledge agents may use citations to find studies that are relevant to the user's query, in particular citation statements are used by scite.ai to answer a question, also providing the associated reference(s).[63]

Wikipedia[edit]

There also has been analysis of citations of science information on Wikipedia or of scientific citations on the site, e.g. enabling listing the most relevant or most-cited scientific journals and categories and dominant domains.[64] Since 2015, the altmetrics platform Altmetric.com also shows citing English Wikipedia articles for a given study, later adding other language editions.[64][65] The Wikimedia platform under development Scholia also shows "Wikipedia mentions" of scientific works.[66] A study suggests a citation on Wikipedia "could be considered a public parallel to scholarly citation".[67] A scientific publication being "cited in a Wikipedia article is considered an indicator of some form of impact for this publication" and it may be possible to detect certain publications through changes to Wikipedia articles.[68] Wikimedia Research's Cite-o-Meter tool showed a league table of which academic publishers are most cited on Wikipedia[67] as does a page by the "Academic Journals WikiProject".[69][70] Research indicates a large share of academic citations on the platform are paywalled and hence inaccessible to many readers.[71][72] "[citation needed]" is a tag added by Wikipedia editors to unsourced statements in articles requesting citations to be added.[73] The phrase is reflective of the policies of verifiability and no original research on Wikipedia and has become a general Internet meme.[74]

Differentiation of semantic citation contexts[edit]

The tool scite.ai tracks and links citations of papers as 'Supporting', 'Mentioning' or 'Contrasting' the study, differentiating between these contexts of citations to some degree which may be useful for evaluation/metrics and e.g. discovering studies or statements contrasting statements within a specific study.[76][77][78]

Retractions[edit]

The Scite Reference Check bot is an extension of scite.ai that scans new article PDFs "for references to retracted papers, and posts both the citing and retracted papers on Twitter" and also "flags when new studies cite older ones that have issued corrections, errata, withdrawals, or expressions of concern".[78] Studies have suggested as few as 4% of citations to retracted papers clearly recognize the retraction.[78] Research found "that authors tend to keep citing retracted papers long after they have been red flagged, although at a lower rate".[79]See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The field of communication (or communications) overlaps with some of the disciplines also covered by the MLA and has its own disciplinary style recommendations for documentation format; the style guide recommended for use in student papers in such departments in American colleges and universities is often The Publication Manual of the APA (American Psychological Association); designated for short as "APA style".

References[edit]

- ^ Munroe, Randall. "Wikipedian Protester". xkcd. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "What Does it Mean to Cite?". MIT Academic Integrity. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ^ Association of Legal Writing Directors & Darby Dickerson, ALWD Citation Manual: A Professional System of Citation, 4th ed. (New York: Aspen, 2010), 3.

- ^ Mansourizadeh, Kobra, and Ummul K. Ahmad. "Citation practices among non-native expert and novice scientific writers." Journal of English for Academic Purposes 10, no. 3 (2011): 152–161.

- ^ Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9781139524827

- ^ Hyland, K., & Jiang, F. (2019). Points of reference: Changing patterns of academic citation. Applied Linguistics, 40(1), 64–85.

- ^ "Oxford Referencing System". Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ "Library glossary". Benedictine University. August 22, 2008. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Jaime A. Teixeira da Silva; Quan-Hoang Vuong (2021). "The right to refuse unwanted citations: rethinking the culture of science around the citation". Scientometrics. 126 (6): 5355–5360. doi:10.1007/s11192-021-03960-9. PMC 8105147. PMID 33994602.

- ^ "Anatomy of a Citation". LIU.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ^ a b "How to cite sources in the body of your paper". BYUI.edu. 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ^ Pantcheva, Marina (nd). "Citation styles: Vancouver and Harvard systems". site.uit.no. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Council of Science Editors, Style Manual Committee (2007). Scientific style and format: the CSE manual for authors, editors, and publishers.

- ^ "Vancouver (Numbering)". University of Birmingham. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ "How to Write Research Papers with Citations: MLA, APA, Footnotes, Endnotes". Archived from the original on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ libguides, liu.cwp. "Parenthetical Referencing". liu.cwp.libguides.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Live Reference Initiative Archived 2021-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ "Citation Formats & Style Manuals". CSUChico.edu. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-02-25. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ "APA Citation Format". Lesley.edu. 2005. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ "APA Citation Format". RIT.edu. 2003. Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ Elizabeth Shown Mills. Evidence Explained : Citing History Sources from Artifacts to cyberspace. 2d ed. Baltimore:Genealogical Pub. Co., 2009.

- ^ The 2nd edition (updated April 2008) of the MHRA Style Guide is downloadable for free from the Modern Humanities Research Association official website. "MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors, Editors, and Writers of Theses". Modern Humanities Research Association. 2008. Archived from the original on 2005-09-10. Retrieved 2009-02-05. (2nd ed.)

- ^ Martin, Peter W (May 2007) [1993]. "Introduction to Basic Legal Citation (LII 2007 ed.)". Cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-10-04. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ Canadian Guide to Uniform Legal Citation (Cite Guide). McGill Law Journal. Updated October 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ^ "Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals" Archived 2019-10-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. "ICMJE Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals – Sample References" Archived 2006-12-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ IEEE Style Manual Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ^ "Pechenik Citation Style QuickGuide" Archived 2015-09-29 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). University of Alberta, Augustana Campus, Canada. Web. November 2007.

- ^ Garfield, Eugene (2006). "Citation indexes for science. A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas". International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (5): 1123–1127. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl189. PMID 16987841.

- ^ Stephen Yoder, ed. (2008). The APSA Guide to Writing and Publishing and Style Manual for Political Science. Rev. ed. August 2006. APSAnet.org Publications Archived 2015-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- ^ "Publishing Style Guide - Stay Informed". www.aaanet.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved Apr 28, 2020.

- ^ Bugeja, Michael and Daniela V. Dimitrova (2010). Vanishing Act: The Erosion of Online Footnotes and Implications for Scholarship in the Digital Age. Duluth, Minnesota: Litwin Books. ISBN 978-1-936117-14-7

- ^ Raymond Hubbard and J. Scott Armstrong (1994). "Replications and Extensions in Marketing: Rarely Published But Quite Contrary" (PDF). International Journal of Research in Marketing. 11 (3): 233–248. doi:10.1016/0167-8116(94)90003-5. S2CID 18205635. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ Peoples N, Østbye T, Yan LL. "Burden of proof: combating inaccurate citation in biomedical literature". BMJ. 2023 Nov 6;383. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076441.

- ^ Serenko, A.; Dumay, J.; Hsiao, P-C.K.; Choo, C.W. (2021). "Do They Practice What They Preach? The Presence of Problematic Citations in Business Ethics Research" (PDF). Journal of Documentation. 77 (6): 1304–1320. doi:10.1108/JD-01-2021-0018. S2CID 237823862. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ Wright, Malcolm; Armstrong, J. Scott (2008). "The Ombudsman: Verification of Citations: Fawlty Towers of Knowledge?". Interfaces. 38 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1287/inte.1070.0317. eISSN 1526-551X. ISSN 0092-2102. JSTOR 25062982. OCLC 5582131729. SSRN 1941335.

- ^ Cumberledge, Aaron; Smith, Neal; Riley, Benjamin W. (2023-08-01). "Unverified history: an analysis of quotation accuracy in leading history journals". Scientometrics. 128 (8): 4677–4687. doi:10.1007/s11192-023-04755-w. ISSN 1588-2861. S2CID 259519993.

- ^ Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 45–80.

- ^ Anauati, Maria Victoria; Galiani, Sebastian; Gálvez, Ramiro H. (November 4, 2015). "Quantifying the Life Cycle of Scholarly Articles Across Fields of Economic Research". Economic Inquiry. 52 (2): 1339–1355. SSRN 2523078.

- ^ van Wesel, M.; Wyatt, S.; ten Haaf, J. (2014). "What a difference a colon makes: how superficial factors influence subsequent citation" (PDF). Scientometrics. 98 (3): 1601–1615. doi:10.1007/s11192-013-1154-x. hdl:20.500.11755/2fd7fc12-1766-4ddd-8f19-1d2603d2e11d. S2CID 18553863. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Brembs, Björn (2018). "Prestigious Science Journals Struggle to Reach Even Average Reliability". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 12: 37. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00037. PMC 5826185. PMID 29515380.

- ^ Crew, Bec (7 August 2019). "Studies suggest 5 ways to increase citation counts". Nature Index. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Hudson, John (2016). "An analysis of the titles of papers submitted to the UK REF in 2014: authors, disciplines, and stylistic details". Scientometrics. 109 (2): 871–889. doi:10.1007/s11192-016-2081-4. PMC 5065898. PMID 27795594.

- ^ Fraser, Nicholas; Momeni, Fakhri; Mayr, Philipp; Peters, Isabell (2019). "The effect of bioRxiv preprints on citations and altmetrics". bioRxiv 10.1101/673665.

- ^ Abramo, Giovanni; D'Angelo, Ciriaco Andrea; Di Costa, Flavia (2016). "The effect of a country's name in the title of a publication on its visibility and citability". Scientometrics. 109 (3): 1895–1909. arXiv:1810.12657. doi:10.1007/s11192-016-2120-1. S2CID 4354082.

- ^ Colavizza, Giovanni; Hrynaszkiewicz, Iain; Staden, Isla; Whitaker, Kirstie; McGillivray, Barbara (2019). "The citation advantage of linking publications to research data". PLOS ONE. 15 (4): e0230416. arXiv:1907.02565. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1530416C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230416. PMC 7176083. PMID 32320428.

- ^ Zhou, Zhi Quan; Tse, T.H.; Witheridge, Matt (2021). "Metamorphic robustness testing: Exposing hidden defects in citation statistics and journal impact factors". IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 47 (6): 1164–1183. doi:10.1109/TSE.2019.2915065.

- ^ Heneberg, P. (2014). "Parallel Worlds of Citable Documents and Others: Inflated Commissioned Opinion Articles Enhance Scientometric Indicators". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 65 (3): 635. doi:10.1002/asi.22997. S2CID 3165853. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ Fister, I. Jr.; Fister, I.; Perc, M. (2016). "Toward the Discovery of Citation Cartels in Citation Networks". Frontiers in Physics. 4: 49. Bibcode:2016FrP.....4...49F. doi:10.3389/fphy.2016.00049.

- ^ Rubin, Richard (2010). Foundations of library and information science (3rd ed.). New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55570-690-6.

- ^ Garfield, E. Citation Indexing - Its Theory and Application in Science, Technology and Humanities Philadelphia:ISI Press, 1983.

- ^ Jaffe, Adam; de Rassenfosse, Gaétan (2017). "Patent citation data in social science research: Overview and best practices". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 68: 1360–1374.

- ^ Derek J. de Solla Price (July 30, 1965). "Networks of Scientific Papers" (PDF). Science. 149 (3683): 510–515. Bibcode:1965Sci...149..510D. doi:10.1126/science.149.3683.510. PMID 14325149.

- ^ Aksnes, Dag W.; Langfeldt, Liv; Wouters, Paul (2019-01-01). "Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories". SAGE Open. 9. doi:10.1177/2158244019829575. hdl:1887/78034. S2CID 150974941.

- ^ Gurevitch, Jessica; Koricheva, Julia; Nakagawa, Shinichi; Stewart, Gavin (March 2018). "Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis". Nature. 555 (7695): 175–182. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..175G. doi:10.1038/nature25753. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29517004. S2CID 3761687.

- ^ a b Park, Michael; Leahey, Erin; Funk, Russell J. (January 2023). "Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time". Nature. 613 (7942): 138–144. arXiv:2106.11184. Bibcode:2023Natur.613..138P. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 36600070. S2CID 255466666.

- ^ Snyder, Alison. "New ideas are struggling to emerge from the sea of science". Axios. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Thompson, Derek (11 January 2023). "The Consolidation-Disruption Index Is Alarming". The Atlantic. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Chu, Johan S. G.; Evans, James A. (12 October 2021). "Slowed canonical progress in large fields of science". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (41). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11821636C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021636118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8522281. PMID 34607941.

- ^ Tejada, Patricia Contreras (13 January 2023). "With fewer disruptive studies, is science becoming an echo chamber?". Advanced Science News. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b Nüst, Daniel; Yücel, Gazi; Cordts, Anette; Hauschke, Christian (4 January 2023). "Enriching the scholarly metadata commons with citation metadata and spatio-temporal metadata to support responsible research assessment and research discovery". arXiv:2301.01502 [cs.DL].

- ^ Beel, Joeran; Gipp, Bela; Langer, Stefan; Breitinger, Corinna (1 November 2016). "Research-paper recommender systems: a literature survey". International Journal on Digital Libraries. 17 (4): 305–338. doi:10.1007/s00799-015-0156-0. ISSN 1432-1300. S2CID 254074596.

- ^ "How does ask a question work?". scite.ai. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Arroyo-Machado, Wenceslao; Torres-Salinas, Daniel; Herrera-Viedma, Enrique; Romero-Frías, Esteban (10 February 2020). "Science through Wikipedia: A novel representation of open knowledge through co-citation networks". PLOS ONE. 15 (2): e0228713. arXiv:2002.04347. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1528713A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228713. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7010282. PMID 32040488.

- ^ "New Source Alert: Wikipedia". Altmetric. 4 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Arroyo-Machado, Wenceslao; Torres-Salinas, Daniel; Costas, Rodrigo (20 December 2022). "Wikinformetrics: Construction and description of an open Wikipedia knowledge graph data set for informetric purposes". Quantitative Science Studies. 3 (4): 931–952. doi:10.1162/qss_a_00226. hdl:10481/80532. S2CID 253107766.

- ^ a b Priem, Jason (6 July 2015). "Altmetrics (Chapter from Beyond Bibliometrics: Harnessing Multidimensional Indicators of Scholarly Impact)". arXiv:1507.01328 [cs.DL].

- ^ Zagorova, Olga; Ulloa, Roberto; Weller, Katrin; Flöck, Fabian (12 April 2022). ""I updated the <ref>": The evolution of references in the English Wikipedia and the implications for altmetrics" (PDF). Quantitative Science Studies. 3 (1): 147–173. doi:10.1162/qss_a_00171.

- ^ Katz, Gilad; Rokach, Lior (8 January 2016). "Wikiometrics: A Wikipedia Based Ranking System". arXiv:1601.01058 [cs.DL].

- ^ "Wikipedia:WikiProject Academic Journals/Journals cited by Wikipedia". Wikipedia. 15 September 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Leva, Federico (21 February 2022). "Wikipedia is open to all, the research underpinning it should be too". Impact of Social Sciences. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Tattersall, Andy; Sheppard, Nick; Blake, Thom; O'Neill, Kate; Carroll, Chris (2 February 2022). "Exploring open access coverage of Wikipedia-cited research across the White Rose Universities" (PDF). Insights: The UKSG Journal. 35: 3. doi:10.1629/uksg.559. S2CID 246504456.

- ^ Redi, Miriam; Fetahu, Besnik; Morgan, Jonathan; Taraborelli, Dario (13 May 2019). "Citation Needed: A Taxonomy and Algorithmic Assessment of Wikipedia's Verifiability". The World Wide Web Conference. WWW '19. San Francisco, CA, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1567–1578. doi:10.1145/3308558.3313618. ISBN 978-1-4503-6674-8. S2CID 67856117.

- ^ McDowell, Zachary J.; Vetter, Matthew A. (2022). "What Counts as Information: The Construction of Reliability and Verifability". Wikipedia and the Representation of Reality. Routledge, Taylor & Francis. p. 34. doi:10.4324/9781003094081. hdl:20.500.12657/50520. ISBN 978-1-000-47427-5.

- ^ Lamers, Wout S; Boyack, Kevin; Larivière, Vincent; Sugimoto, Cassidy R; van Eck, Nees Jan; Waltman, Ludo; Murray, Dakota (24 December 2021). "Investigating disagreement in the scientific literature". eLife. 10: e72737. doi:10.7554/eLife.72737. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 8709576. PMID 34951588.

- ^ Khamsi, Roxanne (1 May 2020). "Coronavirus in context: Scite.ai tracks positive and negative citations for COVID-19 literature". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01324-6. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Nicholson, Josh M.; Mordaunt, Milo; Lopez, Patrice; Uppala, Ashish; Rosati, Domenic; Rodrigues, Neves P.; Grabitz, Peter; Rife, Sean C. (5 November 2021). "scite: A smart citation index that displays the context of citations and classifies their intent using deep learning" (PDF). Quantitative Science Studies. 2 (3): 882–898. doi:10.1162/qss_a_00146. S2CID 232283218.

- ^ a b c "New bot flags scientific studies that cite retracted papers". Nature Index. 2 February 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Peng, Hao; Romero, Daniel M.; Horvát, Emőke-Ágnes (21 June 2022). "Dynamics of cross-platform attention to retracted papers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (25): e2119086119. arXiv:2110.07798. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11919086P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2119086119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9231484. PMID 35700358.

Further reading[edit]

The dictionary definition of citation at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of citation at Wiktionary Quotations related to Citation at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Citation at Wikiquote Media related to Citations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Citations at Wikimedia Commons

- Armstrong, J Scott (July 1996). "The Ombudsman: Management Folklore and Management Science – On Portfolio Planning, Escalation Bias, and Such". Interfaces. 26 (4): 28–42. doi:10.1287/inte.26.4.25. OCLC 210941768. Archived from the original on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Pechenik, Jan A (2004). A Short Guide to Writing About Biology (5th ed.). New York: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 978-0-321-15981-6. OCLC 52166026.

- "Why Are There Different Citation Styles?". Yale.edu. 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-08-27. Retrieved 2015-09-28.