Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | |

|---|---|

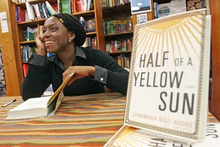

Adichie in 2015 | |

| Born | 15 September 1977 Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Nigerian; American |

| Alma mater | |

| Period | 2003–present |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

Ivara Esege (m. 2009) |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (/ˌtʃɪməˈmɑːndə əŋˈɡoʊzi əˈdiːtʃi.eɪ/ ⓘ[a]; born 15 September 1977) is a Nigerian writer, novelist, poet, essayist, and playwright of postcolonial feminist literature. She is the author of the award-winning novels Purple Hibiscus (2003), Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) and Americanah (2013). Her other works include the book essays We Should All Be Feminists (2014); Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions (2017); a memoir tribute to her father, Notes on Grief (2021); and a children's book, Mama's Sleeping Scarf (2023).

Born in Enugu, Enugu State, Adichie's childhood was influenced by postcolonial rule in Nigeria, including the aftermath of the Nigerian Civil War, which took the lives of both of her grandfathers and was a major theme of Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun. She excelled in academics and attended the University of Nigeria, where she initially studied medicine and pharmacy. She moved to the United States at 19, and studied communications and political science at Drexel University in Philadelphia before transferring to and graduating from Eastern Connecticut State University. Adichie later received a master's degree from Johns Hopkins University. She first published the poetry collection Decisions in 1997, which was followed by a play, For Love of Biafra, in 1998. In less than ten years, she published eight books: novels, book essays and collections, memoirs, and children's books. Adichie has cited Chinua Achebe—in whose house she lived while at the University of Nigeria—Buchi Emecheta, Enid Blyton and other authors as inspirations; her style juxtaposes Western influences and the Igbo language and culture.

Adichie's words on feminism were encapsulated in her 2009 TED talk "We Should All Be Feminists", which was adapted into a book of the same title in 2014. Most of her works delve the themes of immigration, racism, gender, marriage, motherhood and womanhood. In 2023, she made statements about LGBT rights in Nigeria in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, after which she was criticized for being transphobic.

Adichie has received several academic awards and fellowship grants. She was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing and has won the O. Henry Award, Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and the PEN Pinter Prize, among others. She was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008 and inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017.

Early life, education, and family[edit]

Family and background[edit]

Ngozi Adichie, whose English name was Amanda,[3][4] was born on 15 September 1977, in Enugu, Nigeria, as the fifth out of six children, to Igbo parents, Grace (née Odigwe) and James Adichie.[5][6] She made up the name "Chimamanda" in the 1990s to keep her legal English name of "Amanda" and conform with Igbo Christian naming customs of the time,[b] which she admitted in an interview with the Nigerian television personality Ebuka Obi-Uchendu.[3][8] She was raised in Enugu, which lies in the southern part of Nigeria,[9] and had been the capital of the short-lived Republic of Biafra.[10] Her father was born in Abba, Anambra State, and studied mathematics at University College, Ibadan. After graduating in 1957, he worked for a few years and then in 1963, moved to Berkeley, California, to complete his PhD at the University of California. He returned to Nigeria and began working as a professor at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1966.[11] Her mother was born in Umunnachi, Anambra State.[5] James met and married Grace on 15 April 1963,[12] moving together to California.[13] While in the United States, the couple had two daughters.[12] She began her university studies in 1964, at Merritt College in Oakland, California, and then earned a degree in sociology and anthropology from the University of Nigeria.[5][14]

Shortly after the family returned to Nigeria, the Biafran War broke out and James began working for the Biafran government[13] at the Biafran Manpower Directorate.[15] The family lost almost everything including Adichie's maternal and paternal grandfathers during the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom.[16] James wrote that his brother, Michael Adichie, and brother-in-law, Cyprian Odigwe, both fought for Biafra in the war.[15] James' father, David, and his father-in-law both died in refugee camps during the war. Obligated by custom which required the oldest child to bury the father,[13] when the war ended, James went to the refugee camp at Nteje to find his father's body. He was told by officials that those who had died had been buried in a mass grave and were unidentifiable. In a symbolic gesture, James took sand from the site of the mass grave to the cemetery in Abba to bury David with his family.[15]

Education and influences[edit]

After Biafra ceased to exist in 1970, James returned to the University of Nigeria in Nsukka[11][13] while Grace worked for the government at Enugu until 1973 when she became an administration officer at the university, later becoming the university's first female registrar.[5][14] The family stayed at the campus of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, previously occupied by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe.[17] When they moved in, the family included Ijeoma Rosemary, Uchenna "Uche", Chukwunweike "Chuks", Okechukwu "Okey", Ngozi, and Kenechukwu "Kene" and her father was then, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the university.[12][4] Adichie was Catholic and when she was young, she wished she could be a priest.[13] Her family's home parish was St. Paul's Parish in Abba.[15]

As a child, Adichie read only English-language stories,[13] especially by Enid Blyton. Adichie's juvenilia which included stories with characters who were white and blue-eyed, modeled on British children she had read about.[13][18][15] At ten, she discovered African literature and began reading Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe,[17] The African Child by Camara Laye,[18] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's Weep Not, Child and Joys of Motherhood by Buchi Emecheta.[15] Adichie began to study her father's stories about Biafra when she was thirteen. The war occurred before she was born, but in visits to Abba, she saw houses that were destroyed and some rusty bullets on the ground. She would later incorporate her memories and father's descriptions into her novels.[15] Adichie started her education in Igbo and English.[9] Although Igbo was not a popular subject, she continued taking courses in the language throughout high school.[13] She completed her secondary education at the University of Nigeria Campus Secondary School, Nsukka with top distinction in West African Examinations Council (WAEC).[4] and academic prizes.[19] She was admitted to the University of Nigeria, and studied medicine and pharmacy for a year and half.[20] She was also the editor of The Compass, a student-run magazine in the university campus.[21]

Education abroad and early literary efforts[edit]

Adichie published Decisions, a collection of poems, in 1997 and then left for the United States.[18] At the age of 19, she moved from Nigeria to study communications at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[21][19] She wrote For Love of Biafra, a play, in 1998, which was her initial exploration of the theme of war following the Nigerian Civil War.[18] These early works were written under the name Amanda N. Adichie.[3] Two years after moving to the United States, she transferred to Eastern Connecticut State University in Willimantic, Connecticut, where she lived with her sister Ijeoma, who was a medical doctor there.[9] In 2000, she published her short story "My Mother, the Crazy African",[22] which discusses the problems that arise when a person is facing two cultures that are complete opposites from each other.[7]: 297–298 After finishing her undergraduate degree, she continued her pattern of simultaneously studying and pursuing a writing career.[18] While a senior at Eastern Connecticut, she wrote articles for the university paper Campus Lantern.[21] She received her bachelor's degree summa cum laude with a major in political science and a minor in communications in 2001.[9][21] She earned a master's degree from Johns Hopkins University in creative writing in 2003,[21][23] and for the next two years was a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University and taught introductory fiction.[19][18] She then began a course in African studies at Yale University, and completed a second master's degree in 2008.[18][9]Adichie received a MacArthur Fellowship that same year[24] plus other academic prizes, including the 2011–2012 Fellowship of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study from Harvard University.[25] Adichie married Ivara Esege, a Nigerian doctor, in 2009,[13] and their daughter was born in 2016.[26] The family primarily lives in the United States because of Esege's medical practice, but they also maintain a home in Nigeria.[13]

Purple Hibiscus (2003)[edit]

While studying in America, Adichie started researching and writing her first novel entitled Purple Hibiscus; it was written in a period when Adichie was feeling homesickness in the United states. She wrote the story with setting in Nsukka, Nigeria where she considered her home, and with written email, she began sending the work to literary agents in America. It wasn't her first written work, as she addressed no one sees her previous writings in an address at the University of Nairobi.

After sending the manuscript to many publishing houses and agents; she didn't received any response from each of them. The agents who accepted her manuscripts requested the change of the setting. According to Adichie, most of the reasons for the rejections were because of the story's setting in Nigeria, while some ask she do change the setting to America before it's accepted. Adichie held out since it isn't going to be easy changing the setting of a large manuscript. Few days later, she received an email from Diana Pearson, a literary agent working at Pearson Morris and Belt Literary Management seeking for the manuscript with lines saying, "I like this and I'm willing to take a risk on you." Adichie, who was desperate to be published sent her manuscript to the agent, which was turned a book on 30 October, 2003 by Algonquin Books. Another issue came up with the novel; it was marketing and finance, as Adichie was a black and not an African American. It was difficult according to her agent to sell the work, though, Adichie was happy at least her book has been published. According to Otosirieze Obi-Young, the book sold on its own until it was awarded the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for the Best Book, a Hurston-Wright Legacy Award and shortlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction.[27]

Purple Hibiscus was received well internationally, and received positive reviews from book critics. It was published in the United Kingdom on 1 March, 2004 by Fourth Estate, and Adichie also got a new agent, Sarah Chalfant of the Wylie Agency. Adichie was clear in adding racial issues involved in her education which was portrayed by her character Kambili in the book, and in a review by Washington Post, she was praised as "a very much the 21st-century daughter of that other great Igbo novelist, Chinua Achebe."[28] Luke Ndidi Okolo, a lecturer of Nnamdi Azikiwe University, said in a review:[29]

As a matter of fact, Adichie's novel treats clear and lofty subject and themes. But the subject and themes, however, are not new to African novels. The remarkable difference of excellence in Chimamanda Adichie's "Purple Hibiscus", the stylistic variation–her choice of linguistic and literary features, and the pattern of application of the features in such a wondrous juxtaposition of characters' reasoning and thought.

Half of a Yellow Sun (2006)[edit]

Adichie talked about his father's stories and how she has been taking note of them.

Being desperate to be published, she wrote other books, that she may make ground for easy publication acceptance. Her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun was published in 2006 by Fourth Estate in London, UK. It told a story spanning the period before and during the Nigerian Civil War; its title referenced the flag of Biafra, a nation that existed during the war, and the book served as a tribute to her grandfathers whom were found dead in the refugee camp at Nteje, after the war.[30] Adichie has said that very important for her research was Buchi Emecheta's 1982 novel Destination Biafra.[31] Half of a Yellow Sun wad critically analysed and positively acclaimed from many sources; it received the 2007 Orange Prize for Fiction[32] and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.[33] The novel was adapted into a 2014 film of the same title directed by Biyi Bandele.[34] In 2008, she wrote an excerpt entitled "A Private Experience", a short story published in The Observer that portrays the story of two women from different cultures learning to understand each other in the middle of a crisis.[35]

The Thing Around Your Neck (2009)[edit]

Adichie's third book, The Thing Around Your Neck, was written and published in 2009 after an extensive research of marriage and hindrances of feminism while in the US. It is a collection of 12 stories, some already published in issues of magazines, exploring the theme of marriage, love, culture and ethnicity.[36]

One story from the book, "Ceiling", was included in The Best American Short Stories 2011.[37] The collection of stories was critically accepted and Adichie was praised in a review by the Daily Telegraph, as "one who makes storytelling seem as easy as birdsong".[38] In a review by The Times, she was called "Stunning. Like all fine storytellers, she leaves us wanting more".[39]

Americanah (2013)[edit]

Her fourth book, Americanah, was published in 2013 and was listed among the "10 Best Books of 2013" by The New York Times.[40] It was an exploration of a young Nigerian woman encountering racism in America. It was from Adichie, who explored the character Igbo: Ifemelu, being identified by the colour of her skin at arrival to the United States.[41] The book won the National Book Critics Circle Award[42] and the 2017 "One City One Book" selection for best books.[43][44] In 2015, she was co-curator of the PEN World Voices festival in New York.[45] While delivering the festival's closing address, she addressed the issue of racism, which was in keeping with the theme of Americanah:[46]

I will stand and I will speak for the right of everyone, everyone, to tell his or her story.

Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions (2017)[edit]

Adichie's next book, Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, was published in 2017.[47] She has said the book had its origin in an email letter she wrote to a friend who had asked for advice about how to raise her daughter as a feminist.[48] In 2020, it was followed by "Zikora", a stand-alone short story about sexism and single motherhood.[49]

Notes on Grief (2021)[edit]

In 2021, after her father's death, Adichie released a memoir titled Notes on Grief,[50][51] based on an essay of the same title published in The New Yorker the previous year.[52] Adichie was critically praised in reviews of the book, which Kirkus Reviews summed up with the words: "An elegant, moving contribution to the literature of death and dying."[53] Leslie Gray Streeter of The Independent said: "Adichie's words put a welcome, authentic voice to this most universal of emotions, which is also one of the most universally avoided."[54]

Mama's Sleeping Scarf (2022): launch and review[edit]

In 2022, Adichie's first children's book—Mama's Sleeping Scarf, dedicated to her daughter, and using the pen-name "Nwa Grace James"—was announced.[55][56] A year and a half in the writing, because her young daughter rejected the first two drafts as "boring",[57] it was published in September 2023 by HarperCollins.[58]

Style[edit]

Although Adichie is primarily known for her works of fiction and non-fiction, she has also written, plays, poetry, essays, and book reviews. Her writing has received critical acclaim and literary reviews from the mainstream media, and feminist critics have approved of her talks and books. Her use of Igbo words in her work has drawn the attention of critics on popularization of her context, that Chinua Achebe was known for. Adichie has said she grew up bilingual in Nigeria, where she spoke both English and Igbo. Her use of some lines of Igbo in her books was to show her love for the Igbo language and its proverbs; citing her father James Adichie as the architect of Igbo-speaking in her family, "especially when he speaks it without adding any foreign language." Adichie has also expressed her sadness, saying "she feels bad that her father speaks Igbo fluently, while she doesn't and cannot make a philosophical argument in her own native language." Michael Gunn of the University of Uyo and Yusuf Tsojon Ishaya of Federal University, Wukari added that in some of Adichie's text, she makes interesting graphological choices that proves the fact that language offers unwavering possibilities with regard to its lacking usage in literary creative works. Her style of writing uses a descriptive character example; Kambili in Purple Hibiscus and Ifemelu in Americanah.[59]

Lawal M. Olusola, a lecturer at Osun State University, noted figuratively that "Adichie is observed to be Chinua Achebe's literary daughter, for she once lived in Achebe's home when she was ten years old; read Things Fall Apart then, and she believed his halo surrounded her, which explains their easy comprehension and analytic style." He also analysed that "the language patterns in Anthills of the Savannah, also assist Achebe to a remarkable degree in establishing anti-woman position."[60]

I'm not even joking when I say that chocolate is a fundamental part of [my] process of creativity... That perfect in between—not too milky, not too dark. With a bit of hazelnuts. Writing is the love of my life. It's the thing that makes me happiest when it is going well—apart from the people I love...Fiction gives me a transcendent joy [where] I feel as though I am suspended in my fictional walls. Here in Lagos, Nigeria, my desk was made by this furniture maker who's young. It's white with two pullout drawers on either side. On the table itself, I have my laptop and a couple of books. I also happen to have a bottle of a cream liqueur, called Wild Africa Cream. When I'm writing, I don't want any alcohol in my body at all. But when it's not going well, then I'm like, "All right. Maybe we just need to take a swig."

—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in describing her style of creativity on Times of India.[61]

Adichie's writing style has been considered unique, especially in her ability to combine elements of African and Western culture, as testified to in her fourth novel, Americanah. Her writing characteristically focuses on themes of identity, feminism, and postcolonialism, with her prove of witnessing the aftermath shadow of the British colonial rule; evident to her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun. Most of her works has drawn premise from issues regarding racism, psychology, history and philosophy.[62] she is generally described as "lyrical and poetic", since she often uses language to create a fascinating and clear exposure of an imagery to quicky emphasize the theme used. Her style of writing is usually dominated with its sharp wit and humor, irony, satirical phrases, idioms and Igbo proverbs, which she learnt from her father.

Adichie's work, for several reviews incorporates elements of African culture, such as folklore, traditional and hyperbolic exclamations and phrases, and local music. Her exploration of gender and identity seeks to being a technical consciousness to the black, after she faced racism and rejections of manuscripts, especially agents requesting change of setting. Unlike Achebe, Adichie is often known to use her characters as real "in a real living town".

Apart from genital cases, her work is dated historic following her themes on post-colonialism. She often uses her characters to explore the effects of colonialism on African societies and to challenge traditional Western narratives. Adichie often uses her characters to explore the power dynamics between colonizers and colonized and to explore the ways in which colonialism has shaped African societies.

A number of Adichie's writings, including Notes on Grief, challenged the conventions of condemnation and neglect of African rich men. In a speech, she talked about "An American professor who in a review said, her writings weren't authentically African." The professor said, the people wear shoes, drive cars and build houses—which to him, was less a typical African man. Though her characters seems always to be dark-skinned individuals, in comparison to the white-skinned heroes, she believed people shiuld use an old adage to qualify a majority; justifying a whole by part.

Themes[edit]

After war and post colonization[edit]

Adichie's work were based on the Nigerian Civil War, which took the lives of both of her grandfathers and was a major theme of Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun. Accepted widely as a writer of post colonial literature. Half of a Yellow Sun, published in 2006, was among her major story dating Nigeria and Africa during the 1900's, while considering other associated themes of culture, tradition and imperialism. Her works identifies the aftermath of a war and colonialism on various cultures; particularly her country Nigeria and ethnicity of the Igbo people. She was able to explore how different cultures across the world seems to be different as wa seen in her character, Kambili in Purple Hibiscus. Although her influence and writings criticised the British rule (and was seen thoroughly the relationship of her works and that of Chinua Achebe), yet laid an understanding of the nature and importance of knowing ones origin —by postcolonial literature. She cites post-colonism era, "as an art and forum for African literature".

Education[edit]

According to Adichie, Nigerians are graded the most brilliant people in the world, and so, her writings must be limed with education amd its critical impact. In her writing, Adichie portrays existentialism of education especially it's need for women—who were seen as "just wife". Adichie, in Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions mentioned how critical it was for a woman to be educated.

[It] is not enough to simply send young girls to school to learn, but they must also benefit from being socialized in a manner that is not wholly dependent on their status as women.

— Adichie on explaining Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions.

While drawing motive for the value of informal education, Adichie has also approached traditional formal education in Half of a Yellow Sun; she examines the effects of education on multiple characters and was seen in the character Ugwu and the professor of a University Odenigbo. The theme of education was also displayed in her short story, "The Headstrong Historian", one of the 12 stories in her collection, The Thing Around Your Neck. The female character Grace, who was the headstrong historian realised that because the colonial masters downgraded her view of Igbo culture, doesn't in anyway explains its same for everybody. Adichie has been praised for involving education with a suburb setting of Africa, where education was seen by the white as substandard.

Feminism[edit]

One of the major themes of Adichie's work and talks were on Feminism. It was completely seen in her TED talk which was turned into a book of the same title. It was also seen in Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, and Americanah. In a talk with Trevor Noah during a session in the Daily Show stated that "feminism and femininity are not mutually exclusive in her writing. In her statement, she said "being a feminist does not mean you must reject femininity" as she believes that it bears the concept of misogyny." Adichie is also regarded as a fashionista, literally expressed her work "In Why Can't a Smart Woman Love Fashion." Adichie's theme usage narrates that "gender roles are "absolute nonsense." She said, "Nothing should be assigned to a person because of their gender. This is including and not limited to cooking, cleaning, household maintenance, and child rearing. These are all learned skills that every person should know and should not be left to one person in a household." Adichie's literature is most often seen as characters fights for justice against gender and mutualistic marriage.

Motherhood[edit]

Adichie has always pointed the theme of motherhood and direct womanhood. In her work, she cited influenced by Buchi Emecheta, whose most work delves womanhood themes also, especially in her novel Second Class Citizen. Adichie in her "Fifteen Feminist Manifesto" addressed concern and worries to the way "soon-to-be mothers are received for their responsibilities". She also said some serves just as "wife."

In Fifteen Feminist Manifesto, Adichie wrote to her friend that "marriage is a good thing, but its shouldn't be the priority of women." She said "like a young girl after getting her PhD will be ask, when are you getting married?" In Half of a Yellow Sun, she used Olanna as "a torn between her family's view of her as just a pretty face and "ruined by education" to others when she realizes that she wants to have a baby with Odenigbo.

Gender and marriage[edit]

While researching for her writing Purple Hibiscus, Adichie literally explores the theme of marriage and gender oppression. She opposed that the way women are seen for marriage life is totally different from boys. In her essay, We Should All Be Feminists, she explained that women should marry when they want. In an illustration of the essay, she pointed out when Bill Clinton was running for President of America, the description on his twitter handle was founder and in his wife's own was "wife and mother". In a conversation with Trevor Noah, she added that "marriage is a lovely thing, but we teach women in a way we do not teach boys. This, that is the problem."

Americanization[edit]

Most of Adichie's work were influenced by her staying in the United States. Those were seen in her short stories and major works like Americanah. Some critics called it, "a theme of an American Dream"; capturing a sub-theme of immigration as seen by the character Ifemelu. Because of the racism and social segregation she faced, she bears her work that one should be satisfied with their native home. She also have explored homesickness, which was a major effect on her and education in America.

Lectures[edit]

"The Danger of a Single Story"[edit]

Adichie delivered a talk titled "The Danger of a Single Story" for TED in 2009.[63] As of 2024[update], it was one of the top twenty most-viewed TED Talks of all time.[64] In the talk, she expressed her concern for under-representation of various cultures.[65] Adichie explained that, "as a young child, she had often read American and British stories where the characters were primarily of Caucasian origin". In concluding the lecture, she noted the importance of different stories in various cultures and the representation that they deserve. She advocated for a greater understanding of stories, since the world has many culture, saying that "by understanding only a single story, one misinterprets people, their backgrounds, and their histories".[66] Since 2009, she had revisited the topic when speaking to audiences such as the Hilton Humanitarian Symposium of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation in 2019.[67]

"We should all be feminists"[edit]

In 2012, Adichie gave a TEDx talk entitled "We should all be feminists", delivered at TEDxEuston in London. The talk was later published a book of the same title in 2014. In the talk, Adichie shared her experiences of being an African feminist, and views on gender and sexuality. She said particularly to gender, how she's "becoming less interested in the way the West sees Africa, and more interested in how Africa sees itself."[68] Adichie said that the problem with gender is that "it shapes who we are" anf "Gender as it functions today is a grave injustice".[69] On 8 December 2021, Adichie during an interview with BBC News on the responsibility of being a feminist stated that "she did not want another person to define her responsibility and she rather defined her responsibility for herself but did not mind using her platform to speak up for someone else."[70]

Parts of Adichie's TEDx talk were sampled "Flawless" by Beyoncé on 13 December, 2013.[71] When asked in an NPR interview for her reaction to Beyoncé sampling her talk, Adichie responded that anything that gets young people talking about feminism is a very good thing.[14] She later qualified the statement in an interview with the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant: "Another thing I hated was that I read everywhere: now people finally know her, thanks to Beyoncé, or: she must be very grateful. I found that disappointing. I thought: I am a writer and I have been for some time and I refuse to perform in this charade that is now apparently expected of me: 'Thanks to Beyoncé, my life will never be the same again.' That's why I didn't speak about it much."[72]

Nevertheless, Adichie has been outspoken against critics who question the singer's credentials as a feminist and has said: "Whoever says they're feminist is bloody feminist."[73]

"Connecting Cultures"[edit]

On 15 March 2012, Adichie delivered the Commonwealth Lecture 2012 at the Guildhall, London, addressing the theme "Connecting Cultures" and explaining: "Realistic fiction is not merely the recording of the real, as it were, it is more than that, it seeks to infuse the real with meaning. As events unfold, we do not always know what they mean. But in telling the story of what happened, meaning emerges and we are able to make connections with emotive significance."[74][75] On 30 November 2022, Adichie delivered the first of the BBC's 2022 Reith Lectures, inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" speech.[76][77]

Views[edit]

Feminism[edit]

In a 2014 interview, Adichie said on feminism and writing: "I think of myself as a storyteller, but I would not mind at all if someone were to think of me as a feminist writer... I'm very feminist in the way I look at the world, and that world view must somehow be part of my work."[42]

Religion[edit]

Adichie is a Catholic and was raised Catholic as a child, though she considers her views, especially those on feminism, to sometimes conflict with her religion. At a 2017 event at Georgetown University, she stated that religion "is not a women-friendly institution" and "has been used to justify oppressions that are based on the idea that women are not equal human beings".[78] She has called for Christian and Muslim leaders in Nigeria to preach messages of peace and togetherness.[79] Having previously identified as agnostic while raising her daughter Catholic, she has also identified as culturally Catholic. In a 2021 Humboldt Forum, she stated that she had returned to her Catholic faith.[80]

LGBT rights[edit]

Adichie supports LGBT rights in Africa; in 2014, when Nigeria passed an anti-homosexuality bill, she was among the Nigerian writers who objected to the law, calling it unconstitutional and "a strange priority to a country with so many real problems", stating that actual crimes have victims and consensual homosexual conduct between adults does not rise to that standard of crime, making the law unjust.[81] Adichie was also close friends with Kenyan openly gay writer Binyavanga Wainaina;[82] when he died on 1 May 2019 after suffering a stroke in Nairobi, Adichie said in her tribute that she was struggling to stop crying.[83]

Since 2017, Adichie has been repeatedly accused of transphobia, initially for saying that "my feeling is trans women are trans women" in response to the question "Are trans women women?". Adichie later clarified her statement, writing: "[p]erhaps I should have said trans women are trans women and cis women are cis women and all are women. Except that 'cis' is not an organic part of my vocabulary. And would probably not be understood by a majority of people. Because saying 'trans' and 'cis' acknowledges that there is a distinction between women born female and women who transition, without elevating one or the other, which was my point. I have and will continue to stand up for the rights of transgender people."[84]

In 2020, Adichie weighed into "all the noise" sparked by J. K. Rowling's article titled "J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues",[85] calling the essay "perfectly reasonable".[86] Adichie again faced accusations of transphobia, some of which came from Nigerian author Akwaeke Emezi, who had graduated from Adichie's writing workshop.[87] In response to the backlash, Adichie criticized cancel culture, saying: "There's a sense in which you aren't allowed to learn and grow. Also, forgiveness is out of the question. I find it so lacking in compassion."[85]

In a June 2021 essay titled "It Is Obscene", Adichie again criticized cancel culture, discussing her experiences with two unnamed writers who attended her writing workshop and later lambasted her on social media over comments she made about transgender people. She labelled what she called their "passionate performance of virtue that is well executed in the public space of Twitter but not in the intimate space of friendship" as "obscene".[88][89]

In late 2022, she faced further criticism for her views after telling the British newspaper The Guardian saying, "So somebody who looks like my brother – he says, 'I'm a woman', and walks into the women's bathroom, and a woman goes, 'You're not supposed to be here', and she's transphobic?"[90][91][92] PinkNews said that the interview showed that Adichie "remains insensitive to the nuances or sensitivities of the ongoing fight for trans rights" and criticised her for perpetuating "harmful rhetoric about trans people".[91]

Influences and legacy[edit]

Overview[edit]

Toyin Falola, a professor of history, in an interview talked about Nigerian figures whom he believes have been recognized prematurely for their achievements. In his argument, he cited several Nigerian academics whom he called "intellectual heroes"; his list included Adichie, Chinua Achebe, Teslim Elias, Babatunde Fafunwa, Simeon Adebo, Bala Usman, Eni Njoku, Ayodele Awojobi and Bolanle Awe.[93]

Adichie has cited drawing inspiration from Chinua Achebe's 1958 novel Things Fall Apart, which she read at the age of 10. She was also inspired by Buchi Emecheta, upon whose death Adichie said:

We are able to speak because you first spoke. Thank you for your courage. Thank you for your art, Nodu na ndokwa.[94]

Adichie has also acknowledged influences from Camara Laye's The African Child (1953) and the 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby.[95]

In September 2021, Open Country Mag noted in a cover story about Adichie's legacy: "Every one of her novels, in expanding her subject matter, broke down a wall in publishing. Purple Hibiscus proved that there was an international market for African realist fiction post-Achebe. Half of a Yellow Sun showed that that market could care about African histories. The novels say: We can be specific in storytelling."[96]

Awards and recognition[edit]

In 2002, Adichie was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing for her short story, "You in America", which first appeared in Zoetrope: All-Story,[97][98] and her story "That Harmattan Morning", was selected as a joint winner of the BBC World Service Short Story Competition in the same year.[99] Later in 2002, she won the David T. Wong International Short Story Prize 2002/2003, a PEN Center award.[100]

Adichie was the recipient of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2007[33] and was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008.[101]

In 2010, The New Yorker listed her as one of its "20 Under 40" authors,[102] and she was described in The Times Literary Supplement in 2011 as "the most prominent" of a "procession of critically acclaimed young anglophone authors" of Nigerian fiction who are attracting a wider audience, particularly in her second home, the United States.[103] During the 2014 Hay Festival, she was listed in the Africa39 under 40[104] and the Rainbow Book Club project, celebrating UNESCO World Book Capital award in Port Harcourt.[105] Adichie was among the world's "100 Most Influential People" named by Time magazine in 2015.[106]

In 2017, she was elected as one of 228 new members to be inducted into the 237th class of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the highest honours for intellectuals in the United States.[c][108] Adichie was awarded the PEN Pinter Prize in 2018,[109] choosing the imprisoned human rights activist and lawyer Waleed Abulkhair as the International Writer of Courage with whom to share the award.[110]

In 2019, she was named fourth on The Africa Report's list of the "100 Most Influential Africans".[111][112][113] Also in 2019, she was selected as one of 15 women to appear on the cover of British Vogue, guest-edited by Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.[114]

Adichie has been conferred with honorary degrees from several top universities internationally, including from Johns Hopkins University in 2016,[115] Haverford College and the University of Edinburgh in 2017,[116][117] Amherst College in 2018,[118] Université de Fribourg and Yale University in 2019,[119][120] and the Catholic University of Louvain in 2022.[121]

On 13 October 2022, a member of Adichie's communications team told the Nigerian newspaper The Guardian that she had rejected an award that was to be given to her by the government of President Muhammadu Buhari: "The author did not accept the award and, as such, did not attend the ceremony."[122]

On 30 December 2022, Adichie was made the "Odeluwa" of Abba, a Nigerian chief, by the kingdom of Abba in her native Anambra State; she was the first woman to receive such an honour from the kingdom.[123]

Listings[edit]

| Year | Award | Work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Caine Prize | "You in America" | Shortlisted |

| 2002 | BBC World Service Short Story Competition | "That Harmattan Morning" | Won |

| 2002/2003 | David T. Wong International Short Story Prize | Won | |

| 2003 | O. Henry Prize | "The American Embassy" | Won |

| 2004 | Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for Best Debut Fiction | Purple Hibiscus | Won |

| Orange Prize | Shortlisted | ||

| Booker Prize | Longlisted | ||

| Young Adult Library Services Association Best Books for Young Adults Award | Nominated | ||

| 2004/2005 | John Llewellyn Rhys Prize | Shortlisted | |

| 2005 | Commonwealth Writers' Prize: Best First Book (Africa) | Won | |

| Commonwealth Writers' Prize: Best First Book (overall) | Won | ||

| 2006 | National Book Critics Circle Award | Half of a Yellow Sun | Nominated |

| 2007 | British Book Awards: "Richard & Judy Best Read of the Year" | Nominated | |

| James Tait Black Memorial Prize | Nominated | ||

| Commonwealth Writers' Prize: Best Book (Africa) | Shortlisted | ||

| PEN Beyond Margins Award | Won | ||

| Orange Broadband Prize: Fiction category | Won | ||

| International Dublin Literary Award | Won | ||

| 2008 | Reader's Digest Author of the Year Award | Won | |

| Future Award, Nigeria: Young Person of the Year category | Won[124] | ||

| 2009 | International Nonino Prize[125] | Won | |

| Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award | The Thing Around Your Neck | Longlisted | |

| John Llewellyn Rhys Prize | Shortlisted | ||

| 2010 | Commonwealth Writers' Prize: Best Book (Africa) | Shortlisted | |

| Dayton Literary Peace Prize | Nominated | ||

| 2011 | This Day Awards: "New Champions for an Enduring Culture" | Nominated | |

| 2013 | Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize: Fiction category | Americanah | Won |

| National Book Critics Circle Award: Fiction category[126][127] | Won | ||

| 2014 | Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction[128] | Shortlisted | |

| Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction[129] | Shortlisted | ||

| MTV Africa Music Awards 2014: Personality of the Year[130] | Nominated | ||

| 2015 | International Dublin Literary Award[131][132] | Americanah | Shortlisted |

| Grammy Awards: Album of the Year[133] | Beyoncé (as featured artist) | Nominated |

Talks and appearances[edit]

- 2015: Wellesley College[134]

- 2017: Williams College[135]

- 2018: Harvard University[136]

- 2019: Yale University[137]

Writings[edit]

Books[edit]

- ——— (1997). Decisions (poetry). London: Minerva Press. ISBN 9781861064226.

- ——— (1998). For Love of Biafra (play). Ibadan: Spectrum Books. ISBN 9789780290320.

- ——— (2003). Purple Hibiscus (novel). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780007189885

- ——— (2006). Half of a Yellow Sun (novel). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780007200283.

- ——— (2009). The Thing Around Your Neck (short-story collection). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780007306213.

- ——— (2013). Americanah (novel). New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307271082.

- ——— (2014). "We Should All Be Feminists" (essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780008115272. (excerpt in New Daughters of Africa; edited by Margaret Busby, 2019)[138]

- ——— (2017). "Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions" (essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780008275709.

- ——— (2021). Notes on Grief (memoir/personal essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 9780593320808.[139][50]

- ——— (2023). Mama's Sleeping Scarf (children picture book). London/New York: HarperCollins Children's Books/Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780008550073.

Selected short fiction[edit]

- ——— (4 June 2006). "Sierra Leone, 1997". The New Yorker..

- ——— (22 January 2007). "Cell One". The New Yorker.

- ——— (16 June 2008). "The Headstrong Historian". The New Yorker.

- ——— (28 December 2008). "A Private Experience". The Observer.

- ——— (1 February 2010). "Quality Street". Guernica.

- ——— (20 September 2010). "Birdsong". The New Yorker.

- ——— (18 March 2013). "Checking out". The New Yorker. Vol. 89, no. 5. pp. 66–73.

- ——— (13 April 2015). "Apollo". The New Yorker. Vol. 91, no. 8. pp. 64–69.

- ——— (3 July 2016). "'The Arrangements': A Work of Short Fiction". The New York Times Book Review.

- ——— (October 2020). "Zikora: A Short Story". Amazon Original Stories.[49]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ CHI-mə-MAHN-də əng-GOH-zee ə-DEE-chee-ay Adichie's name has been pronounced a variety of ways in English. This transcription attempts to best approximate the Igbo pronunciation for English-speaking readers.

- ^ In translation, the Igbo name "Chimamanda" means "my spirit is unbreakable" or "My God cannot fail".[7]

- ^ Adichie was the second Nigerian to be given the honour after Wole Soyinka.[107]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Brockes, Emma (4 March 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'Can people please stop telling me feminism is hot?'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Front Row. 3 May 2013. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Nwankwọ, Izuu (2023). "Traditions of Naming in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Fiction". postcolonial.org. 18 (3).

- ^ a b c Anya, Ike (15 October 2005). "In the Footsteps of Achebe: Enter Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". African Writer. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Chimamanda's Mother for Burial May 1". This Day. 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Luebering, J.E. "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | Biography, Books, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ a b Tunca, Daria (2010). "Of French Fries and Cookies: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Diasporic Short Fiction". In Kathleen Gyssels; Bénédicte Ledent (eds.). Présence africaine en Europe et audelà | African Presence in Europe and Beyond (PDF). Paris: L‟Harmattan. pp. 291–309. See p. 300.

- ^ Akinyoade, Akinwale (5 January 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi adichie reveals how she came about the name 'Chimamanda'". Guardian. Nigeria. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Mullane, Janet (2014). Lawrence J. Trudeau (ed.). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Contemporary Literary Criticism. 364. Gale Literature Resource Center: Gale.

- ^ Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2001). Ethnic Politics in Kenya and Nigeria. Nova Science Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 9781560729679.

- ^ a b "James Nwoye Adichie (1932 – 2020)". The Sun. Nigeria. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's parents' memoirs (2) Knowing each other before you marry". The Sun. Nigeria. 14 September 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j MacFarquhar, Larissa (28 May 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Comes to Terms with Global Fame". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Martin, Michel (18 March 2014). "Feminism Is Fashionable For Nigerian Writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (interview)". Tell Me More, NPR. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Otosirieze (20 September 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now". Open Country Mag. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (15 September 2006). "Truth and lies". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b Murray, Senan (8 June 2007). "The new face of Nigerian literature?". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tunca, Daria (2011). Henry Louis Gates Jr; Emmanuel K. Akyeampong (eds.). "Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (1977)". African Biography. 1. Oxford University Press: 94–95. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195382075 (inactive 6 April 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^ a b c "CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE, a pride to Africa, a treasure to the world". Business Day. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Agbo, Njideka (26 September 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The fearless writer". The Guardian Nigeria. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Braimah, Ayodale (13 February 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (1977–)". BlackPast.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Adichie, Amanda Ngozi (2000). "My Mother, the Crazy African". In Posse Review. Multi-Ethnic Anthology. San Francisco, California: Spectrum Publishers. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Curriculum Vitae: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Krieger School of Arts & Sciences | Johns Hopkins University Magazine. 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Irvine, Lindesay (24 September 2008). "Adichie wins a $500,000 genius grant". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Okachie, Leonard (19 May 2011). "In the News | Chimamanda Selected as Radcliffe Fellow". National Mirror. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Chutel, Lynsey (3 July 2016). "Award-winning author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has had a baby, not that it's anyone's business". Quartz. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Obi-Young, Otosirieze (15 October 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Purple Hibiscus Turns 15: The Best Moments of a Modern Classic". Brittle Paper. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "A Moveable Feast". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Okolo, luke Ndudi (2016). Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto (ed.). "THEMATIC AND STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF CHIMAMANDA ADICHIE'S PURPLE HIBISCUS". Ansu Journal of Language and Literary Studies. 1 (3).

- ^ "Half of a Yellow Sun: Summary & Analysis". study.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Busby, Margaret (3 February 2017). "Buchi Emecheta obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Majendie, Paul (6 June 2007). "Nigerian author wins top women's fiction prize". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- ^ a b "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | Half of a Yellow Sun". The 82nd Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (10 November 2013). "Half of a Yellow Sun: London Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (28 December 2008). "A Private Experience: A short story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". The Observer. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "The Thing Around Your Neck: Stories". Kirkus Reviews. 1 May 2009. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Sam-Duru, Prisca (22 January 2014). "Chimamanda Adichie, a growing literary prodigy". Vanguard News. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Jane Shilling (2 April 2009). "The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Review". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Lech Mintowt-Czyz (24 March 2012). "UK News, World News and Opinion". The Times. Entertainment.timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ "The 10 Best Books of 2013". The New York Times. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "'Americanah' Author Explains 'Learning' To Be Black In The U.S." Fresh Air. NPR. 27 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ a b Hobson, Janell (2014). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Storyteller". Ms. No. Summer. pp. 26–29. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ "Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment Announces Americanah as Winner of Inaugural 'One Book, One New York' Program". NYC | Press Releases. Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Weller, Chris (16 March 2017). "New Yorkers just selected a book for the entire city to read in America's biggest book club". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Sefa-Boakye, Jennifer (17 February 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Co-Curates PEN World Voices Festival In NYC With Focus On African Literature". PEN America. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Lee, Nicole (11 May 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'Fear of causing offence becomes a fetish'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Award-Winning Novel Purple Hibiscus is the 2017 One Maryland One Book". mdhumanities.org. Maryland Humanities. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Greenberg, Zoe (15 March 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Blueprint for Feminism". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b Law, Katie (29 October 2020). "Zikora: A Short Story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie review: a taut tale of sexism and single motherhood". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ a b Gerrard, Nicci (9 May 2021). "Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie review – a moving account of a daughter's sorrow". The Observer. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (11 February 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to publish memoir about her father's death". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Lozada, Carlos (6 May 2021). "In grieving for her father, a novelist discovers the failure of words". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Notes on Grief". Kirkus Reviews. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Streeter, Leslie Gray (16 May 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Notes on Grief captures the bewildering messiness of loss – review". The Independent. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Otosirieze (4 April 2022). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Children's Picture Book Coming in 2023". Open Country Mag. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Ibeh, Chukwuebuka (7 April 2022). "Chimamanda Adichie Debuts Children's Book Under the Pseudonym Nwa Grace James". brittlepaper.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Krug, Nora (12 September 2003). "Chimamanda Adichie's children's book has no agenda beyond joy". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Mama's Sleeping Scarf". HarperCollins Publishers. September 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Ishaya, Yusuf Tsojon; Gunn, Michael (2022). "Graphology as style in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's The Thing Around Your Neck". LWATI: A Journal of Contemporary Research. 19 (1): 69–86.

- ^ Olusola, Lawal M. (2015). "Stylistic Features and Ideological Elements in Chimamanda Adichie's Purple Hibiscus and Chinua Achebe's Anthills of the Savannah". International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL). 3 (4): 1–8. eISSN 2347-3134. ISSN 2347-3126.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie On Her Writing Quirks And How She Deals With Writer's Block". Times of India. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Anthony, Joseph (9 April 2023). "Exploring the Literary Genius of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Herald Nigeria. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (July 2009). "The danger of a single story". ted.com. TEDGlobal 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "3700+ talks to stir your curiosity". ted,com. TED. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (July 2009). "The danger of a single story — Transcript". ted.com. TEDGlobal 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Brown, Annie (2 May 2013). "The Danger of a Single Story". Facing History and Ourselves. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Rios, Carmen (21 October 2019). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Warns Humanitarians About the Danger of a Single Story". Ms. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Dabiri, Emma. "Re-Imagining Gender in Nigeria". Norient.com. Norient. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (December 2012). We should all be feminists (video). TEDxEuston.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The responsibility of being a feminist icon – 100 Women, BBC World Service". 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Raymer, Miles (4 September 2014). "Billboard' Hot 100 recap: Beyonce's 'Flawless' finally hits the chart". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Kiene, Aimée (7 August 2016). "Ngozi Adichie: Beyoncé's Feminism Isn't My Feminism". De Volkskrant. The Netherlands. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020.

- ^ Danielle, Britni (20 March 2014). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Defends Beyoncé: 'Whoever Says They're Feminist is Bloody Feminist'". Clutch Magazine. UK. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Prize winning author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to speak at Commonwealth Lecture". thecommonwealth.org. The Commonwealth. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Commonwealth Lecture 2012: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 'Reading realist literature is to search for humanity'". Commonwealth Foundation. London, UK. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Four speakers to deliver the BBC Radio 4 Reith Lectures 2022 | Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lord Rowan Williams, Darren McGarvey and Dr Fiona Hill to deliver lectures inspired by Franklin D Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech". Media Centre. BBC. 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie delivers BBC Reith Lecture on Freedom of Speech". Vanguard. Nigeria. 1 December 2022. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Award-Winning Author Adichie Explores Faith, Feminism at Georgetown Event". Georgetown University. 17 March 2017. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Shariatmadari, David (13 January 2012). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: religious leaders must help end Nigeria violence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Grenier, Elizabeth; Hucal, Sarah (22 September 2021). "Humboldt Forum tackles colonial issue with new museums". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (19 February 2014). "Anti-Gay Law: Chimamanda Adichie Writes, 'Why can't he just be like everyone else?'". NewsWire NGR. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Malec, Jennifer (26 July 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie pays touching tribute to Binyavanga Wainaina: 'A great and rare and genuine talent'". The Johannesburg Review of Books. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Dayo, Bernard (28 May 2019). "Read Chimamanda Adichie's elegantly moving tribute to Binyavanga Wainaina and cry with us". YNaija. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. "Clarifying". Facebook. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ a b Allardice, Lisa (14 November 2020). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'America under Trump felt like a personal loss'". The Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020.

- ^ Okafor, Chinedu (17 November 2020). "Chimamanda Adichie comes under same fire as Rowling over transphobia". YNaija. Nigeria. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020.

- ^ Akhabau, Izin (18 November 2020). "Akwaeke Emezi: Non-binary author shares heartbreak at Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". The Voice. UK. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozie (15 June 2021). "IT IS OBSCENE: A TRUE REFLECTION IN THREE PARTS". Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Flood, Alison (16 June 2021). "'It is obscene': Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie pens blistering essay against social media sanctimony". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

we have a generation of young people on social media so terrified of having the wrong opinions that they have robbed themselves of the opportunity to think and to learn and to grow. I have spoken to young people who tell me they are terrified to tweet anything, that they read and re-read their tweets because they fear they will be attacked by their own. The assumption of good faith is dead. What matters is not goodness but the appearance of goodness. We are no longer human beings. We are now angels jostling to out-angel one another. God help us. It is obscene.

- ^ Williams, Zoe (28 November 2022). "'I believe literature is in peril': Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie comes out fighting for freedom of speech". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b Baska, Maggie (1 December 2022). "Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie doubles down on anti-trans views". PinkNews. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Ring, Trudy (2 December 2022). "Novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Goes Anti-Trans Again". Advocate. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Olaopa, Tunji (27 November 2022). "An Encounter with Toyin Falola: Between Celebration and Canonization of Intellectuals – THISDAYLIVE". www.thisdaylive.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Celebrating Buchi Emecheta". Library blog. Goldsmiths, University of London. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Cruz, Riza (29 March 2022). "Shelf Life: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Elle. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Otosirieze (20 September 2021). "Cover Story: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on 'Half of a Yellow Sun' at 15, Her Private Losses and Public Evolution". Open Country Mag. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Jackson, A. Naomi (17 June 2010). "Chimamanda Adichie: Interview". Mosaic. No. 17–2007. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Previous Shortlisted Writers". The Caine Prize for African Writing. UK. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013.

- ^ "Short Story Competition 2002". bbc.co.uk. BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Half of a Yellow Sun". pen.org. PEN America. 9 August 2007. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Chimamanda Adichie – MacArthur Foundation". 27 January 2008. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Knox, Jennifer L. (7 July 2010). "20 Under 40: Q. & A.: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021.

- ^ Copnall, James (16 December 2011). "Steak Knife". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 20.

- ^ "List of artists". hayfwstival.com. Africa 39. Archived from the original on 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Port Harcourt World Book Capital – Africa 39: Meet the Authors III". Port Harcourt World Book Capital. Nigeria. 30 September 2014. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014.

- ^ Jones, Radhika (16 April 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The World's 100 Most Influential People". Time. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Sola (12 April 2017). "Chimamanda elected into US Academy of Arts and Science". Punch Newspapers. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "American Academy of Arts and Sciences Elects 228 National and International Scholars, Artists, Philanthropists, and Business Leaders". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wins 2018 PEN Pinter Prize". International PEN. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Flood, Alison (9 October 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie accepts PEN Pinter prize with call to speak out". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "The 100 most influential Africans (1–10)". The Africa Report. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Chimamanda makes 100 most influential Africans' list". guardian.ng. 6 October 201. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Top 10 Nigerians in Africa Report's 100 most influential Africans". Ventures Africa. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ "Meghan Markle puts Sinéad Burke on the cover of Vogue's September issue". The Irish Times. 29 July 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Eight to receive Johns Hopkins honorary degrees at commencement ceremony". HUB. Johns Hopkins University. 22 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Commencement 2017 Honorary Degrees". Haverford College. 15 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Acclaimed author receives honorary degree". ed.ac.uk. The University of Edinburgh. 28 July 2017. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017.

- ^ "2018 Honorees". amherst.edu. Amherst College. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021.

- ^ "L'écrivaine nigériane Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie devient docteure honoris causa de l'Université de Fribourg". unifr.ch (in French). Université de Fribourg. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023.

- ^ "Biographies of Yale's 2019 honorary degree recipients". YaleNews. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Chimamanda to receive 16th honorary PhD from the Catholic University of Louvain Belgium". guardian.ng. The Guardian. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Olaiya, Tope Templer (13 October 2022). "Chimamanda Adichie did not accept national honour, team confirms". The Guardian Nigeria News — Nigeria and World News. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Ujumadu, Vincent (1 January 2023). "Chimamanda becomes first woman to receive chieftaincy title in hometown". Vanguard News. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Ogbu, Rachel (27 January 2008). "Tomorrow Is Here". Newswatch. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Adichie Wins the Nonino". African Writing Online, No. 6. 17 May 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Announcing the National Book Critics Awards Finalists for Publishing Year 2013". National Book Critics Circle. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "National Book Critics Circle Announces Award Winners for Publishing Year 2013". National Book Critics Circle. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Brown, Mark (7 April 2014). "Donna Tartt heads Baileys women's prize for fiction 2014 shortlist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Italie, Hillel (30 June 2014). "Tartt, Goodwin awarded Carnegie medals". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ "Mafikizolo, Uhuru, Davido lead nominations for MTV Africa Music Awards". Sowetan LIVE. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "The 2015 Shortlist". International Dublin Literary Award. 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Flood, Alison (15 April 2015). "Impac Dublin prize shortlist spans continents". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Commencement Address by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Wellesley College. 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Commencement Address 2017". Commencement. 2017. Archived from the original on 4 September 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie named Class Day speaker". Harvard Gazettte. Harvard University. 19 April 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Cho, Serena (3 March 2019). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie GRD'08 to speak at Class Day". yaledailynews.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Hubbard, Ladee (10 May 2019). "Power to define yourself: The diaspora of female black voices". TLS. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (10 September 2020). "Notes on Grief". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Emenyonu, Ernest N. (2017). A Companion to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. James Currey/Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1847011633.

- Sarantou, K. (2019). Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. United States: Cherry Lake Publishing.ISBN 9781534146976

- Tunca, Daria (ed.), Conversations with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. (2020). United States: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781496829283

- Of This Our Country: Acclaimed Nigerian Writers on the Home, Identity and Culture They Know. (2021). United Kingdom: HarperCollins Publishers.ISBN 9780008469283

- Onyebuchi, Tochi (2021). (S)kinfolk: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Americanah. United States: Fiction Advocate. ISBN 9780999431696

- Ojo, Akinleye Ayinuola (2018). "Discursive Construction of Sexuality and Sexual Orientations in Chimamanda Adichie's Americanah". Journal of English Studies. 7. Ibadan, Nigeria.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Adichie on Twitter

- Adichie on Facebook

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on the Muck Rack journalist listing site

- Britannica about Adichie

- Unofficial website via Daria Tunca, English Department, University of Liège.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at TED

- "The Danger of a Single Story". ted.com. TED. 2009.

- "We should all be feminists". TEDx Euston. 12 April 2013.

- Messud, Claire, ed. (1 February 2010). "Quality Street". Guernica. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010.

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (15 January 2012). "Why Are You Here?". Guernica.

- Murray, Senan (8 June 2007). "The new face of Nigerian literature?". BBC News.

- "Michio Kaku, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Angela Hobbs" (Audio). The Forum. BBC World Service. 13 April 2008.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Commonwealth Lecture 2012 on YouTube. Commonwealth Foundation, 16 March 2012.

- "Why Chimamanda Adichie Will Not 'Shut Up'". Publishers Weekly. Frankfurt Book Fair 2018. 19 October 2018.

- "'I am a pessimistic optimist': Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie answers authors' questions". The Guardian. 4 December 2020.

- 1977 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Nigerian dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Nigerian poets

- 20th-century Nigerian women writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- 21st-century essayists

- 21st-century Nigerian educators

- 21st-century Nigerian novelists

- 21st-century American academics

- 21st-century American women academics

- 21st-century Nigerian women writers

- 21st-century non-fiction writers

- 21st-century short story writers

- 21st-century women educators

- African-American women academics

- American short story writers

- American women dramatists and playwrights

- American women short story writers

- American writers of African descent

- Drexel University alumni

- Eastern Connecticut State University alumni

- English-language poets

- Feminism and transgender

- Feminist writers

- Igbo academics

- Igbo activists

- Igbo dramatists and playwrights

- Igbo educators

- Igbo novelists

- Igbo poets

- Igbo short story writers

- Igbo women writers

- Johns Hopkins University alumni

- MacArthur Fellows

- Nigerian dramatists and playwrights

- Nigerian essayists

- Nigerian expatriate academics in the United States

- Nigerian feminists

- Nigerian Roman Catholics

- Nigerian short story writers

- Nigerian women academics

- Nigerian women dramatists and playwrights

- Nigerian women educators

- Nigerian women essayists

- Nigerian women novelists

- Nigerian women poets

- Nigerian women short story writers

- O. Henry Award winners

- The New Yorker people

- Wesleyan University faculty

- Writers from Enugu

- Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni