Charles Garvice

Charles Andrew Garvice | |

|---|---|

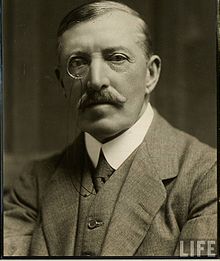

Charles Andrew Garvice's portrait | |

| Born | 24 August 1850 Stepney, London, England, UK |

| Died | 1 March 1920 (aged 69) |

| Pen name | Charles Garvice, Caroline Hart, Chas. Garvice, Charles Gibson |

| Occupation | writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1875–1919 |

| Genre | Romance |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Jones |

| Children | 8 |

Charles Garvice (24 August 1850[1] – 1 March 1920[nb 1]) was a prolific British writer of over 150 romance novels, who also used the female pseudonym Caroline Hart. He was a popular author in the UK, the United States and translated around the world.[3] He was ‘the most successful novelist in England’, according to Arnold Bennett in 1910.[1] He published novels selling over seven million copies worldwide by 1914, and since 1913 he was selling 1.75 million books annually, a pace which he maintained at least until his death.[4] Despite his enormous success, he was poorly received by literary critics, and is almost forgotten today.[4]

Biography[edit]

Personal life[edit]

Charles Andrew Garvice was born on 24 August 1850 in or around Stepney, London, England,[4] son of Mira Winter and Andrew John Garvice, a bricklayer. In 1872, he married Elizabeth Jones, and had two sons and six daughters.[5] Garvice suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on 21 February 1920 and was in a coma eight days until his death on 1 March 1920.[4]

Until recently not much has been known about Garvice's personal life. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography said "Little .. is known of his family origins and personal life. Obscurity envelops [him]."[1] John Sutherland in the Companion to Victorian Literature said "Little is known of Garvice's life."[6] In 2010, English freelance author and editor Steve Holland did an exhaustive search of baptismal records, genealogy databases and census records to build a picture of his early life.[5]

Garvice is buried in Richmond Cemetery.[7] W. Somerset Maugham, who met him at The Garrick, described Garvice as "a modest, unassuming, well-mannered man. I am convinced that when he sat down to turn out another of his innumerable books, he wrote as one inspired, with all his heart and soul."[8]

Writing career[edit]

Garvice got his professional start as a journalist.[4] His first novel, Maurice Durant (1875), was marginally successful in serialized form, but when published as a novel, it was a "dismal failure".[4][9] He concluded it was too long and too expensive for popular sales - this early experience taught him about the business side of writing.[4] He would spend the next 23 years writing serialized stories for the periodicals of George Munro.[4] Magazine stories included A Modern Juliet, Woven in Fate's Loom, On Love's Altar, His Love So True, and A Relenting Fate. The unexpected success of Just a Girl (1895) in America brought him attention in the UK and encouragement to resume his career as a novelist - from then on every novel he published became a best-seller in England.[4][9] He reworked many of his magazine stories as novels, and by 1913, Garvice was selling 1.75 million books annually, a pace which he maintained at least until his death.[4][9] Garvice published over 150 novels, selling over seven million copies worldwide by 1914.[4] Just a Girl was filmed in 1916. According to Garvice's agent Eveleigh Nash, Garvice's books were as "numerous in the shops and on the railway bookstalls as the leaves of Vallombrosa."[4] He was 'the most successful novelist in England', according to Arnold Bennett in 1910.[1]

In 1904, capitalizing on his wealth as a best-selling author, Garvice bought a farm estate in Devon, where he wanted to work the land in "the genuine, dirty, Devonshire fashion."[4][9] Like the characters in his novels, he romantically dreamed of a life happily ever after, lord of a country manor. He wrote about it in his one non-fiction book A Farm in Creamland.[5]

Critical reception[edit]

Garvice's novels were formulaic predictable melodramas.[4] They usually told the story of a virtuous woman overcoming obstacles and achieving a happy ending.[4] He could crank out 12 or more novels a year, but "Little beyond the particulars of the heroines' hair color differentiates one from another," says modern critic Laura Sewell Matter, who found his stories "boring".[4] Likewise contemporary critics were almost unanimous in their disregard, but he was hard to ignore because of his best-selling status.[2] As the London Times wrote in his obituary:[4]

- "It cannot be said that his work was of a high order; but criticism is disregarded by his own frank attitude towards the possibility of the permanence of his literary reputation. His answer to a captious friend who seemed solicitous to disabuse him on this score was merely to point with a gesture to the crowds on the seaside beach reading. "All my books," he said: "they are all reading my latest." It was a true estimate.[4]

In contemplating why his novels were so popular, Laura Sewell Matter said:

- "[Garvice] endured more public ridicule [by critics] than any decent human being deserves. What [Thomas] Moult and other critics failed to acknowledge, but what Garvice knew and honored, are the ways so many of us live emotionally attenuated states, during times of peace as well as war. Stories like the one Garvice wrote may be low art, may not be art at all. They may offer consolation or distraction rather than provocation and insight. But many people find provocation enough in real life, and so they read for something else. One cannot have contempt for Garvice without also having some level of contempt for common humanity, for those readers - not all of whom can be dismissed as simpletons - who may not consciously believe in what they reading, but who read anyway because they know: a story can be a salve."[4]

Bibliography[edit]

Garvice was particularly popular in the United States, producing over 150 novels, twenty-five of which were written under the pseudonym Caroline Hart.[5]

As Charles Garvice[edit]

|

|

|

As Caroline Hart[edit]

- Lil, The Dancing Girl. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 3), 1909.

- Women Who Came Between. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 5), 1909.

- Nameless Bess; or, The Triumph of Innocence. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 12), 1909.

- That Awful Scar; or, Uncle Ebe’s Will. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser.), 1909.

- Vengeance of Love. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, 1909?

- Redeemed by Love. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 26), 1910

- A Hidden Terror; or. The Freemason’s Daughter. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 36), 1910.

- Madness of Love. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 48), 1910?

- A Working-Girl's Honor; or. Elsie Brandon’s Aristocratic Lover. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 50), 1911.

- A Woman Wronged; or, The Secret of a Crime. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 69), 1911.

- Angela's Lover. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, 1911.

- From Worse Than Death. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 105), 1912?

- A Strange Marriage. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook (Hart ser. 110), 1912.

- For Love or Honor. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- From Want to Wealth. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Game of Love. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Haunted Life. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Hearts of Fire. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Lillian's Vow. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Little Princess. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Love's Rugged Path. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Nobody's Wife. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- Rival Heiresses. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- She Loved Not Wisely. Cleveland, Arthur Westbrook, n.d.

- The Woman Who Came Between. Cleveland, Economy Books League, 1933.

Collections[edit]

- My Lady of Snow and other stories. New York. G. Munro's Sons (Laurel Library 59), 1900?

- The Girl Without a Heart and other stories. London, Newnes, 1912.

- A Relenting Fate and other stories. London, Newnes, 1912.

- All Is Not Fair in Love and other stories. London, Newnes, 1913.

- The Tessacott Tragedy and other stories. London, Newnes, 1913.

- The Millionaire’s Daughter and other stories. New York, Street & Smith (New Eagle ser. 982), 1915.

- The Girl at the 'bacca Shop. London, Skeffington, 1920.

- Miss Smith's Fortune and other stories. London, Skeffington, 1920.

Other[edit]

Omnibus

- Four Complete Novels (contains: Just a Girl, On Love’s Altar, A Jest of Fate, Adrien Leroy). London, 1931.

Verse

- Eve and other verses. Privately printed, 1873.

Non-fiction

- A Farm in Creamland. A book of the Devon countryside. London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1911; New York, Doran, 1912.

Others

- The Red Budget of Stories, edited by Garvice. London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1912.

Plays

- The Fisherman's Daughter (produced London, 1881).

- Marigold, with Allan F. Abbott (produced Glasgow, 1914).

Further reading[edit]

- Kemp, Sandra (1997). "Garvice, Charles". Edwardian Fiction: An Oxford Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 145.

- Holland, Steve (20 February 2010). "Charles Garvice". Bear Alley.

- Matter, Laura Sewell (Fall 2007). "Pursuing The Great Bad Novelist". Georgia Review. 61 (3).

- Waller, Philip J. (2006). "In Cupid's Chains: Charles Garvice". Writers, Readers, and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain, 1870-1918. Oxford University Press. pp. 681–701.

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to Philip Waller, there is "some mystery" as to the exact day of death. See footnote #1 pg. 681[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Waller, Philip (2004). "Garvice, Charles Andrew (1850–1920)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38692.

- ^ a b Waller, Philip J. (2006). "In Cupid's Chains: Charles Garvice". Writers, Readers, and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain, 1870-1918. Oxford University Press. pp. 681–701.

Charles Garvice is unsung. His name was noted tersely in the original Oxford Companion to English Literature (ed. Sir Paul Harvey, 1932) but removed from the new edition (ed. Margaret Drabble, 1985). Nevertheless, Garvice's works outsold most of his contemporaries. People in the book trade and other commercially minded authors knew this.

- ^ Bloom, Clive (2008). Bestsellers: Popular Fiction Since 1900. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 118-119, 58. ISBN 978-0-230-53688-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Matter, Laura Sewell (Fall 2007). "Pursuing The Great Bad Novelist". Georgia Review. 61 (3).

- ^ a b c d Holland, Steve (20 February 2010). "Charles Garvice". Bear Alley.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1990) [1989]. "Garvice, Charles". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Literature. Stanford University Press. pp. 238–239. ISBN 9780804718424.

- ^ Meller, Hugh; Parsons, Brian (2011). London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer (fifth ed.). Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. pp. 290–294, 292. ISBN 9780752461830.

- ^ Maugham, W. Somerset (1949) [1915]. A Writer's Notebook. Doubleday & Company. p. 349.

- ^ a b c d Kemp, Sandra (1997). "Garvice, Charles". Edwardian Fiction: An Oxford Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 145.

External links[edit]

- Works by Charles Garvice at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Charles Garvice at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Charles Garvice at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Caroline Hart at Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Garvice at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)